I want you to ask yourself one question

If you had twenty-four hours to live, what would you do?

That’s some deep shit right there, a lot of pressure

How would you handle it?

— Puff Daddy, “24 Hours to Live”

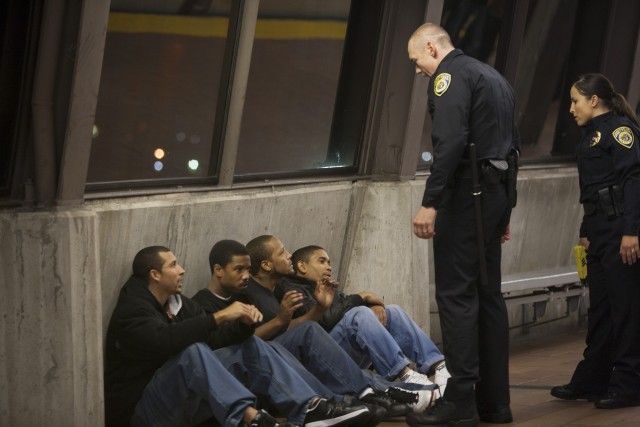

At some point late in Fruitvale Station — the new Sundance-winning film based on the last day in the life of 22-year-old Oscar Grant, who was shot to death in a Bay Area Rapid Transit station in Oakland on New Year’s Day 2009 — the viewer sees Grant waiting for his girlfriend, Sophina, to return from the bathroom before embarking on the fatal ride. It occurred to me then that as far as last days go, Grant’s was pretty damn extraordinary.

Think about it.

He gave love. He made love. He did a couple of good deeds. He offered comfort. He kicked a crippling habit. He came clean to his lady and came through for his family. He laughed. He cried. He made amends and made friends. He ate a favorite meal. He had time alone to reflect on his past. Time with loved ones to celebrate the present. Time to hope for the future.

Any of us would be so lucky. We’ve all contemplated how we’d like our last day on earth to play out if we knew it was all the time we had left. Who we would see. What we would say and do. Everything is heightened in these scenarios because in death’s grip, life is most fully realized. It’s the stuff of movies and music, the source of “live everyday like it’s your last” maxims, part of the reason that last rites, last words and meals of death row inmates intrigue many of us.

Fact is, we have to live without knowing when our time will be up. We cope by making plans as if we’ll always have more time to give love, make love, come clean, eat a favorite meal, etc. And justifiably so — not only would life be unbearable otherwise, but we actually are living longer, healthier lives than ever. I have it on good authority that 60 is the new 50, which is the new 40, and so on. The estimable Steven Pinker has proven to the satisfaction of millions of smart people that we live in the safest time in human history. A new study in the Annals of Emergency Medicine has even declared U.S. cities safer than their rural counterparts.

My intention isn’t to make light of the figurative or literal Oscar Grant’s death at the hands of a BART police officer whose ostensible duty was to protect him. Rather, it’s to wrestle meaning from a movie that is, strictly speaking, inspired by a senseless tragedy. And what Fruitvale director Ryan Coogler does so well is ground us in our mortality. His film reminds us that everyone isn’t sharing equally in the intrepid advance toward an ageless and death-free society. Mothers still worry about whether their sons will become statistics. Sons still wonder if they’ll be able to pay rent without returning to the corner. Daughters still watch their daddies walk out the door never to return.

Mostly, though, the film reveals how our unresolved racial legacy still infects our present day, and it does so without resorting to melodrama or cliché, which was my biggest fear.

Despite the accolades, acclaim and high praise from some of my most respected friends, it took me three weeks to see Fruitvale. I was afraid that it was going to try so hard to make a grand statement about the current state of racism that it wound up stilting the story and smothering the art. I was equally concerned that Grant would be characterized as a saintly avatar of the black male’s unjust predicament, the tragic martyr elevated to stain-free myth by the Hollywood reenactment machine.

My fears were totally unwarranted.

In Fruitvale Station, I encountered something far more subtle and difficult to pin down than I could have envisioned. I’d go so far as to say the story’s lasting power may not reside in its parallels to Trayvon Martin, but in its grasp of a modern ethos spawned from social media. Yes, we demand transparency and authenticity, but we’re willing to be more understanding and forgiving in exchange.

Simply put, gray is the new black and white. We get to see the self-medicating and self-sabotaging Grant, but we also see him being supportive, reflective and remorseful. He’s quick to anger, yet he’s just as swift to give even when he doesn’t have. He lies to cover up his shame, but also to shield others. He dies tragically but lives a beautifully full last day.

This consistent unvarnished interplay between Grant’s dark and light sides challenges us to think for ourselves and ask our own questions, even the less flattering ones: What if things hadn’t gotten better for him? What if he didn’t find a new job? Would he really have changed in the long run? Would he have remained faithful to Sophina?

Octavia Spencer portrays Grant’s mother, Wanda Johnson, as having muted initial response to her son’s death. This triggers its own a set of challenging questions for us to wrestle with: Had she resigned herself to this ending long ago? Or had she believed her faith and diligence would ultimately protect her child? We’re accustomed to mother characters in Johnson’s situation telegraphing their anguish, so when she quietly absorbs the news we’re left to feel our way through on our own.

In my solitude I realized I was hoping for a miracle that defied the logic of a biopic. I knew perfectly well that the real Oscar Grant’s life ended in a hospital the next morning. Still, as irrational as it sounds, I’d hoped that his character in Fruitvale would live by the closing credits. What can I say? I was in the grip.

On my way home after the film I found myself thinking about, of all things, the previews. They featured four black films: The Best Man Holiday, Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom, The Butler and Black Nativity. One is a feel-good reunion story, two are historical dramas and the fourth is a musical. (The Weinstein Company, which released Fruitvale, is also distributing all four of these films.) They tell different stories, are set in different times, feature different actors and cater to different audiences.

I’m not interested in seeing all of them, but I’m delighted that they all exist. For decades the Hollywood machine has resisted rolling out multiple black movies for fear of oversaturating the market. The underlying thesis has been threefold: Black filmgoers are happy just to see black people on the screen, there aren’t enough black filmgoers to make multiple black movies profitable, and only black people are willing to pay to see black leads on the screen.

That all three myths appear to be unraveling is significant. It means every black film won’t have to carry the burden of appealing to every black filmgoer, every black script won’t require an overwrought diatribe about the state of racial affairs, and every young black lead won’t have to be a symbol of an entire generation’s plight. Ultimately, it may even mean there’s space for Trayvon Martin’s story to be genuinely and compellingly told as well.

Dax-Devlon Ross is the author of five books and has written essays and articles for a range of publications, including Time and the New York Times. He is a non-profit higher-education consultant and the executive director of After-School All-Stars NY-NJ. You can find him at daxdevlonross.com.