“Democracy….we have started toward a new integration—-to an integration along the horizontal line which we call the great highway.”

— Frank Lloyd Wright, September 1931

In 1928, Frank Lloyd Wright had an idea that was to become an obsession. He was sixty-one-years old. After a very public and tumultuous divorce with his second wife, he finally married Olga Ivanovna, his long-time mistress. He was ready to start anew. He wanted to craft his legacy with the same meticulousness with which he built his houses.

At this time, most architects were scheming to fix the modern city. According to the late urban sociologist Leonard Reissman, urban planners of the time fell into three basic categories: The first wanted to radically transform the modern city into something better, the second wanted to build small communities that would connect to larger cities through public transportation (the English model, which most American architects sought to emulate), and the third category wanted to rid the world of the industrial city altogether. Frank Lloyd Wright was the most radical, most stubborn, and most influential of this last rare species. “Wright felt the city and the industrial civilization that produced it must perish,” Reissman wrote. “They were the consequences of diseased values, and to achieve health, new values had to be established in a new environment.”

Broadacre City was fully branded in 1932, when the New York Times Magazine invited Wright to respond to an article they had published by Wright’s nemesis Le Corbusier, who proposed a grand urban scheme called The Radiant City, the apotheosis of vertical growth, where soaring skyscrapers would house 2,700 people a pop, and interior streets would connect one building to the next – not unlike today’s Hong Kong. Wright’s rebuttal was called “Broadacre City: An Architect’s Vision.”

By 1932, Broadacre was a living, breathing behemoth of Wright’s imagination. He clung to it until his death in 1959. To describe the essence of Broadacre, it is best to concede the floor to Wright’s first full description of it, which appeared in his short 1932 book, optimistically entitled The Disappearing City.

Imagine spacious landscaped highways …giant roads, themselves great architecture, pass public service stations, no longer eyesores, expanded to include all kinds of service and comfort. They unite and separate — separate and unite the series of diversified units, the farm units, the factory units, the roadside markets, the garden schools, the dwelling places (each on its acre of individually adorned and cultivated ground), the places for pleasure and leisure. All of these units so arranged and so integrated that each citizen of the future will have all forms of production, distribution, self improvement, enjoyment, within a radius of a hundred and fifty miles of his home now easily and speedily available by means of his car or plane. This integral whole composes the great city that I see embracing all of this country—the Broadacre City of tomorrow.

These words were written before suburban sprawl became America’s architectural legacy and the source of social discontent. Wright is sometimes remembered as the prophet of suburbia and environmental degradation. He called for “a new standard of space measurement—the man seated in his automobile.” He thought every person should have a car and, eventually, an “aerator”—a helicopter that could land without a landing strip.

Even in the 1930s, urban planners were disgusted by Broadacre. Its philosophy was deeply individualistic; its layout was conspicuously wasteful. Liberals of the time who emulated the socialist spirit of Europe classified Wright as an anti-government eccentric, which indeed he was. In 1938, Marxist art historian Meyer Schapiro condemned Broadcre City as “perfectly consistent with physical and spiritual decay.”

Yet Wright’s intention was to create a functional community, not a conglomerate of individuals. He was disgusted by the squalor and aesthetic ugliness of city life, and craved a return to the land. In 1932 he wrote that man needed “more light, more freedom of movement and a more general spatial freedom in the ideal establishment of what we call civilization.”

Anthony Alofsin – architect, art historian, Frank Lloyd Wright expert, and professor at the University of Texas – believes Broadacre’s legacy as a precursor to suburbia is an enduring misconception. “In fact, Broadacre isn’t like the suburbs at all,” Alofsin says. “That’s fallacious. Broadacre had a variety of building types and social and cultural activities within a very limited population frame that is different from what we think of as a conventional suburb.”

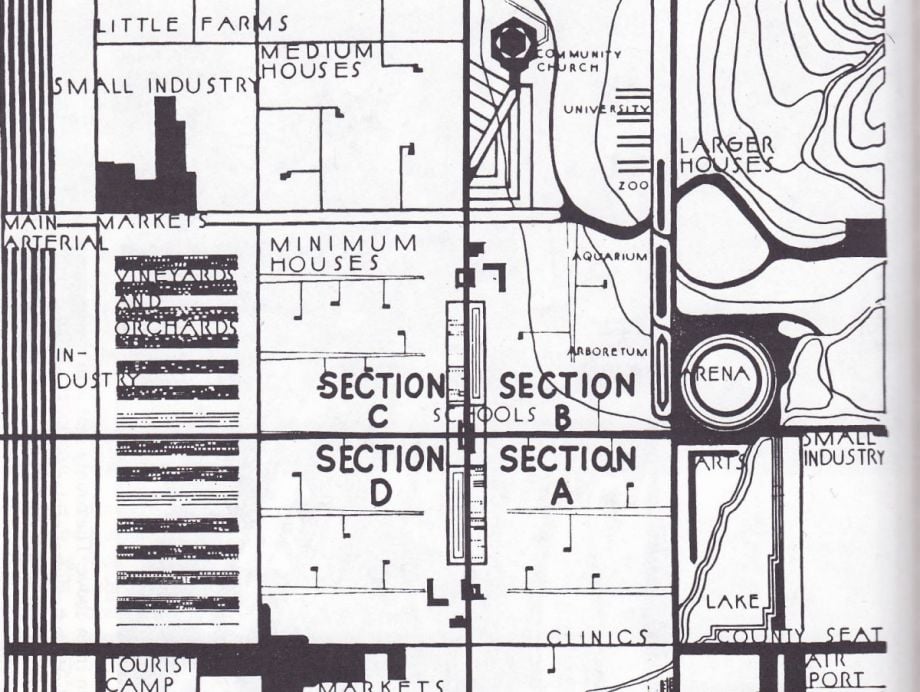

To test this claim, it is best to again concede the floor to Wright himself. The first full-out diagram of Broadacre was published in 1935 in Architectural Record, and that same year a Broadacre model was displayed at Rockefeller Center. At Broadacre’s center were one-acre land units meant for nuclear families. Expanding from this center, Wright designated distinct areas that included: little farm units; “luxurious” type (non-farm) housing; orchards; hotel; sanitarium; music garden; zoo; aquarium; little factories; scientific and agricultural research; and a “small school for small children.” On one panel of the Rockefeller Model were a series of Orwellian negations that included:

No Slum. No Scum

No traffic problems

No glaring cement roads or walks

In 1976, Wright historian John Sergeant wrote “Broadacre City has been regarded either as an enigma or simply as irrelevant.” The confusion comes from Broadacre’s minute specificity combined with its maddening imprecision. While Wright specified the largest number of children that should be allowed in a single school (40), the actual diagrams of Broadacre remained vague because Wright never had the opportunity to build it. In 1958, one year before his death, he wrote that “Broadacre City was the concept; the plan and model were suggestions for the realization of the concept and only for one of the larger villages, the administrative center.”

Wright imagined a flowering of small cities covering the entire United States, all connected by a superhighway. Each city would be embedded in nature and have its own cultural and educational centers. Wright’s “larger villages” would contain only about 10,000 individuals. In every way, Broadacre was an alternative to the mega-city. Wright, an ardent individualist, also hated money (“the modern city is its stronghold and chief defender”), land rent and landlords, and above all, profit and bureaucracy. He wrote, “Out of America’s ‘rugged individualism’ captained by rugged captains of our rugged industrial enterprises we have gradually evolved a crude, vain power: plutocratic ‘capitalism.’ Not true capitalism. I believe this is entirely foreign to our own original idea of democracy.” Regarding the inevitability of suburban sprawl, Wright was not naïve. He knew population growth would push Americans out of the cities; that some intermediary between urban and rural would arise. What he wanted was to harness this inevitability, to direct its flow. In 1958, already witnessing the dark sides of suburbanization, Wright wrote, “America needs no help to Broadacre City. It will haphazard build itself. Why not plan it?”

Today, urban planners seek to reverse suburban sprawl and restore a sense of community to American life. “The suburbs are not ever going to look like older cities,” says urban designer Gerald Gast, co-owner of the San Francisco-based Gast Miller Urban Design, “but I think they can develop centers that are more compact and more walkable and more transit-oriented, and you’re starting to see that happen; people today are more astute about transportation and reducing automobiles.”

As for Broadacre, Gast says it was an impossibility from the beginning, due to the dramatic population explosion that Wright could not have imagined. “We just don’t have that kind of land available, unless cities fall out altogether,” says Gast. “I think his vision would have been a more beautiful version of suburbia, if you had the land.”

Wright really wanted the city to fall out altogether, and like a post-apocalyptic pioneer, he wanted to shape its replacement. The closest he ever came to Broadacre’s realization was in 1943, when he compiled a “Citizens’ Petition” signed by sixty-four Broadacre sympathizers, including Albert Einstein, John Dewey, and Nelson Rockefeller. He sought unlimited cash flow to dot the American landscape with Broadacres. He never got it. In the petition, Wright wrote:

Inevitably, there will develop a new form of community life, but just what it will be except as Broadacre City tentatively outlines it as free to grow, who can say? Not I. Who is going to say how humanity will eventually be modified by all these spiritual changes and physical advantages, sound and vision coming through solid walls to men, each aware of anything in or of the world he lives in without lifting a finger, making it unnecessary to go anywhere unless it is a pleasure to go. The whole psyche of humanity is changing and what that change will ultimately bring as future community I will not prophecy. It is already greatly changed.