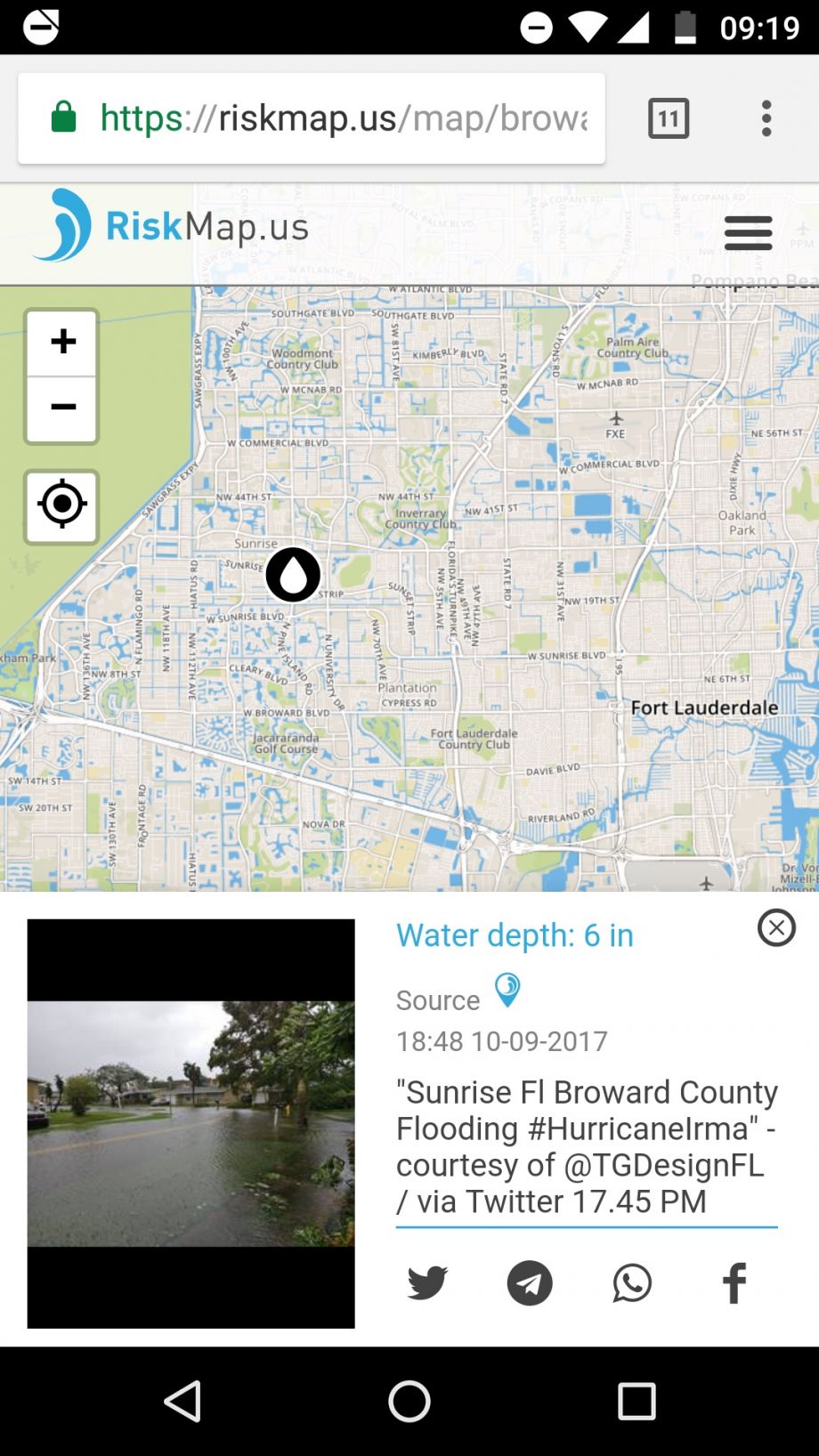

As Hurricane Irma approached the state of Florida last week, one county was equipped with a tool that others didn’t have. In partnership with the Urban Risk Lab at MIT, Broward County launched Riskmap.us, a public reporting platform for disaster management.

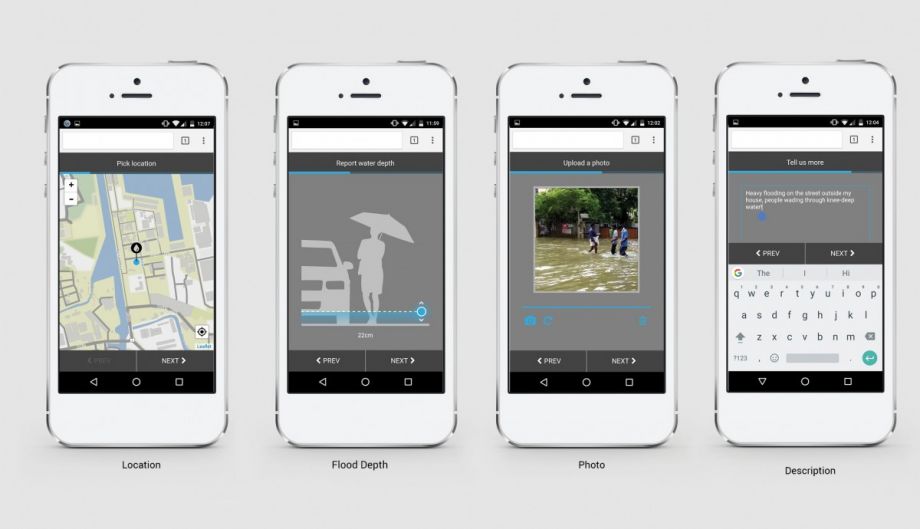

Home to Fort Lauderdale and almost 2 million residents, Broward County had been working with the Risk Lab in the months preceding the hurricane to develop the first version of the software in the U.S. The platform is designed to encourage the public to report high water levels and other hazards using photos and text through existing social media and messaging platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Telegram. Users’ data automatically populates a map available to city officials, emergency management teams and residents alike.

The first version of the software was launched in January in Jakarta, Indonesia. Forty percent of Jakarta is below sea level, and it experiences seasonal flooding during the monsoon season, which is exacerbated by rapid urbanization and aging infrastructure. A month after the software, dubbed PetaBencana.id there, launched, there was a major flooding event. Over 300,000 residents used the software. It was featured on local TV and was used by Uber drivers to figure out places they should avoid.

Residents’ reports were used to create a risk evaluation matrix for emergency management officials in Jakarta, who could color-code all the data according to water levels. While they were able to do this before through more cumbersome data collection, tapping the power of the public allowed them to exponentially increased their bandwidth. And now, the reports update in real time.

In the U.S., Broward County wasn’t planning to launch Riskmap until October, but as Irma approached, county officials and MIT researchers made a last-minute call to go live.

“When we saw the path that Hurricane Irma was taking, we said ‘well we should really try to get it live,” says Miho Mazereeuw, director of the Urban Risk Lab at MIT. But because it hadn’t been scheduled to roll out until October, word hadn’t gotten out about Riskmap in the same way it had had when major floods hit in Jakarta. “It was a pilot,” Mazereeuw says. “We didn’t have time to do all the outreach to the public, so we recognize that there were a lot of people that didn’t know about it.”Tomas Holderness, a research scientist in the MIT Department of Architecture who led the system design, says that because Irma didn’t end up being as strong in Broward County as predicted, the site only received a handful of social media posts. Still, he writes via email, the pilot was useful. “It allowed us to test the system in the U.S. with [a] relatively low number of users, and test the newly created Facebook bot. Additionally, we collected lots of useful information to help improve the system, such as other types of hazards to collect (e.g., power outage, trees blocking the road) and [a] number of UI improvements.” Holderness says that throughout the weekend when Irma approached the United States and made landfall, 15,762 people visit the Riskmap.us site.

Riskmap.us isn’t the only emerging disaster response technology. As more and more cities deal with flooding and severe weather events, data-driven tools are being developed to track not just hazards but also things like labor. As Houston deals with the aftermath of recent Hurricane Harvey, for example, Mayor Sylvester Turner has asked volunteers and city staffers to log hours spent on recovery efforts using ReportYourHours.com. This could help to ensure the city receives a full reimbursement from FEMA. And a variety of apps worldwide engage citizens in disaster reporting and recovery efforts. But Mazereeuw stresses the strength of Riskmap.us is that it’s not an app.

“It’s meant for people to be able to report in the platform that they’re already comfortable using,” she says. “A lot of people don’t download emergency apps unless they’re in the emergency, and that’s not a good time to be downloading.”

In Jakarta, PetaBencana.id was successful because people knew about it. It was launched with a major media event, and residents there are already inclined to use social media. (Jakarta has one of the highest concentrations of Twitter users on the planet.) Plus, with the floods coming a month after the launch, the platform was still fresh in people’s minds. The system had another advantage in Jakarta, too. There, Twitter gave the platform a Power Tracker: With a few keywords flagged, any time someone in Jakarta posted the word, “banjir” (flood), or a handful of other words, they would receive a message from a Chatbot, linking them to the PetaBencana.id platform and asking them to report their data.It hasn’t been decided if Riskmap.us will get Power Tracker capability. For now, no keywords are tracked. Broward County officials worry that the perception that government is listening in on tweets would make citizens less likely to report hazards, and the whole point of the software is to engender a sense of stewardship towards one’s city, not mistrust. The researchers also say trust and transparency are key to preventing users from sending out false information or fake pictures via the platform. The system is linked to social media profiles, and they hope that because the messages populate a map that everyone has access to, that will also help to deter false reporting.

Mazereeuw says that for the platform to be successful, residents should be comfortable using it all the time, not just during emergencies.

“With all disaster management tools, you don’t want people to have to remember how to do it at that critical moment when there’s panic and chaos,” she says.

To do this, Mazereeuw says residents need to know they can use the platform during King tides and minor flooding, too. The Risk Lab has been in touch with cities in India that would like to use the software for monsoon preparedness — reporting clogged or blocked drains — as a way to both identify problem areas for emergency management officials ahead of time, and to familiarize residents with the platform so they know to use it during an emergency.

Nina Feldman is an independent journalist focused on audio production. She worked as a regular contributor to NPR member station WWNO in New Orleans and as editor at American Routes. Her work has also appeared on Marketplace, Morning Edition and PRI's The World.

_1200_700_s_c1_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)