The COP21 climate summit, an event some have called “our last, best chance to save the planet,” captured the world’s attention this past week. The many dangers under discussion include one that forms a basis for global health: food security. Among grim realities, a crop of innovation is flourishing.

The situation presents a stark challenge. This September, the United Nations announced its new Sustainable Development Goals, a list of 17 broad global health and development goals. A previous eight-point list (dubbed the Millennium Development Goals) helped countries to pursue global development from 2002 to 2015, and work toward a reduction in worldwide hunger. The new SDGs aim for hunger eradication by 2030. But barely six weeks after the list’s release, a team from the World Bank published a report demonstrating that climate change poses a grave threat to several of the goals — including food security. In fact, climate change could plunge 100 million people worldwide into extreme poverty by 2030, in part by harming crop productivity.

The impact on health is clear. At a COP21 press conference, World Food Programme Executive Director Ertharin Cousin noted that “drought can increase the probability of stunting” — children’s failure to grow to their full height due to prolonged malnutrition — “by 50 percent.” More generally, hunger also compromises cognitive functioning, physical strength and energy, and disease resistance, reducing overall health and productivity, leading to increased poverty and therefore deepening hunger.

Worse, the issue itself is now a double bind: Burning the carbon necessary to reduce poverty and hunger in low-income countries would accelerate climate change, undoing those very same achievements. As the World Bank team, led by Stéphane Hallegatte, wrote in Shock Waves: Managing the Impacts of Climate Change on Poverty, “There is a consensus that current development trends are incompatible with these internationally agreed climate targets” of a 2 C increase in temperature over pre-industrial global average. This November, Australian researchers published a study documenting the environmental costs and economic benefits of 33 “development corridors” throughout Africa — including roads, railroads, pipelines and ports meant to augment farming, resource extraction and economic prosperity. Lead researcher William F. Laurance concluded, “Several of the corridors could be environmentally disastrous, in our view.” He added, “The trick — and it’s going to be a great challenge — will be to amp up African food production without creating an environmental crisis in the process.”

“Ending poverty and stabilizing climate change will be two unprecedented global achievements, and …. they need to be jointly tackled through an integrated strategy,” Hallegatte’s team asserted. What is that strategy?

In reality, there are many. For Laurance, pulling the plug on planned developments — particularly those that offer less prosperity at higher environmental risk — is part of the answer. That will not offset the risks to health that climate change creates through disastrous storms, loss of crop productivity and drought, but will help stop climate change from worsening.

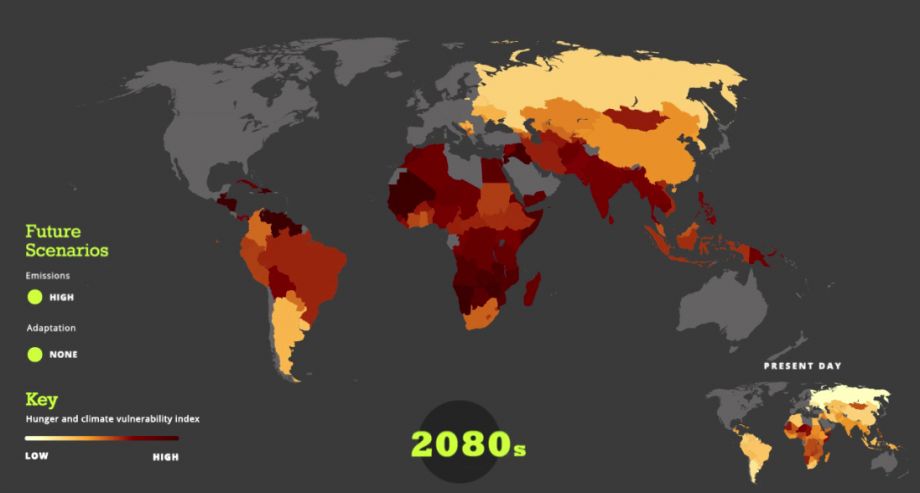

For the World Food Programme, the answer has to do with monitoring and evaluating the situation and its management. At COP21, the organization launched the Food Insecurity and Climate Change Vulnerability Index.

“This simulates how the world response — or lack of response — to climate change impacts will affect food security across the entire global community,” Cousin explained. “This tool demonstrates the constant vigilance required not only to achieve zero hunger, but to maintain and sustain any achievements made.” She added, “This tool creates public awareness,” a necessary part of keeping pressure on governments to ensure food security programs receive support.

To date, those additional programs include the Climate Adaptation Management and Innovation Initiative (C-ADAPT), which works to complete food insecurity analyses and best practices for mitigation and adaptation. This expanded repository of information would create a crucial expansion of the world’s current limited predictive abilities. (As Shockwaves notes, “According to the IPCC, changes in temperature and precipitation are likely to result in higher food prices by 2050, but the magnitude remains highly uncertain, with increases ranging from 3 to 84 percent without CO2 fertilization effects, and between decreases of 30 percent and increases of 45 percent with CO2 fertilization.”) In addition, the World Food Programme has launched an initiative to ensure safe and ecologically sound methods of cooking are available in food-insecure regions.

Shockwaves advocates policy strategies to help developing-world residents, most often targeted to the increases in food prices that could plunge millions into poverty. (While food producers might benefit from increased prices, these gains will only work on balance with productivity — the very thing climate change threatens — and therefore is likely to be temporary.) The report advises that stabilizing food prices in urban centers is a vital part of avoiding hunger. In addition, “food stocks, better access of poor farmers to markets, improved technologies, and climate-smart production practices can reduce climate impacts,” from both sudden “productivity shocks” and longer-term declines.

Of these, improved technologies pose a particular difficulty. “Adoption of new technological packages is often slow and limited,” the report notes. “For instance, in Africa, fertilizer application remains low because of high transport costs and poor distribution systems. Furthermore, cultural barriers, lack of information and education, and implementation costs need to be overcome.”

Here, the World Bank plan comes up against a dissenting view — illustrating the tension between development and climate, but adding a strategy that could treat the problem at its root. In a recent op-ed in the Washington Post, food experts Debbie Barker and Michael Pollan wrote about agricultural techniques that reduce atmospheric carbon:

Their methods include cover crops, no-till farming and crop rotation — simple strategies that can pull tons of carbons out of the air in short periods of time, and that might even be amenable to existing systems in the developing world too.

The “Health Horizons: Innovation and the Informal Economy” column is made possible with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation.

M. Sophia Newman is a freelance writer and an editor with a substantial background in global health and health research. She wrote Next City's Health Horizons column from 2015 to 2016 and has reported from Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Kenya, Ghana, South Africa, and the United States on a wide range of topics. See more at msophianewman.com.

Follow M. Sophia .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)