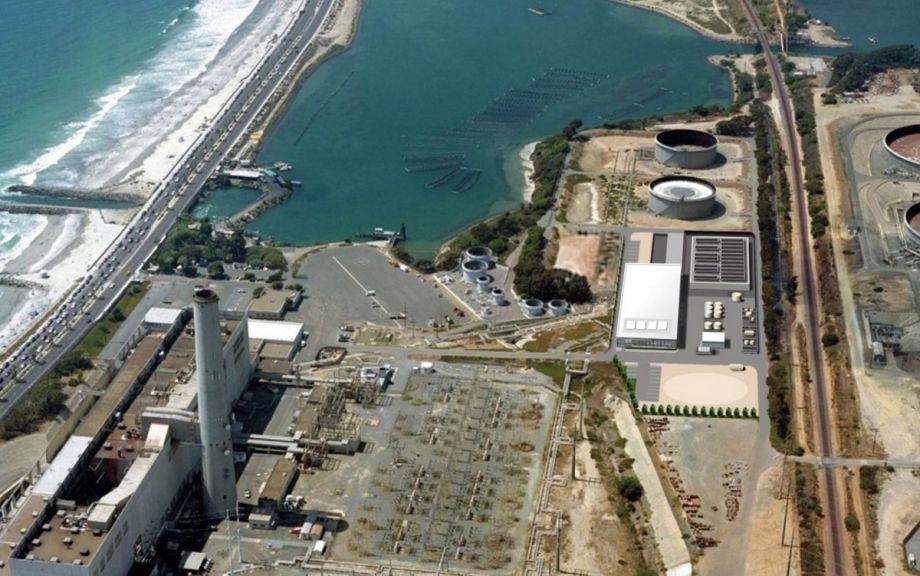

In 2016, after nearly a decade of debate and scrutiny, some residents of sunny, drought-stricken Southern California will start drinking water pulled from the vast Pacific Ocean that laps at their shores. If all goes according to plan, a $1 billion privately financed desalination facility — located in Carlsbad, a short drive up the coast from San Diego — will begin delivering 50 million gallons of drinking water per day to the people of San Diego County.

It will be the largest desal facility in the Western Hemisphere, and its proponents hail it as a reliable source of water in a perennially thirsty state, where a three-year dry spell has highlighted just how fragile the state’s water resources are, and how great the threat a lack of water poses to the viability of the California dream.

“This plant can’t come online fast enough,” Bob Yamada, of the San Diego County Water Authority told the Sacramento Bee. “It’s drought-proof. That’s one of the most important attributes. It will be the most reliable water source we have.”

Yet, even with that touted relief, the Carlsbad facility alone isn’t likely to erase desal skeptics’ worries over everything from fish to money.

The ocean-to-tap project’s course has been fraught with obstacles. The Boston-based Poseidon Water first proposed the Carlsbad plant nearly a decade ago and was immediately met with opposition from environmental groups and went through a stiff six-year permitting process meant to protect the state’s 840 miles of coastline. The slow pace of desalination development in California can’t be blamed entirely, however, on concerns about marine life and the huge amounts of fossil-fueled energy desal requires. (About 15 plants are currently moving through the process, but others have given up.)

The hard truth about desal is that it is expensive. That’s because, despite advances in technology over the past decade, the reverse-osmosis process that turns saltwater into fresh still requires lots of expensive and delicate equipment, and a whole lot of energy.

The holy grail for water researchers and engineers is a desalination process that is energy-efficient, environmentally friendly and relatively cheap. The tantalizing promise of desal means that a lot of people are working on finding that elusive prize, with some promising early results.

In California’s Central Valley, a startup project that uses solar power to purify contaminated irrigation runoff from the area’s huge agricultural industry has had promising early results, and is scaling up to increase production from 14,000 to two million gallons per day. In Texas and California, where there are large reserves of brackish water not far below the surface, some experts say desalination might be more energy-efficient than pumping water over long distances. And when it comes to accessing saltwater supplies on the California coast, using slanting boreholes to access seawater from land might be less environmentally disruptive than pumping directly from the ocean.

New technologies might also drastically reduce the energy required for desalination. Tiny “water chips” that use an electrical charge to desalinate water have been developed by researchers at the University of Texas at Austin and the University of Marburg in Germany, and could provide a low-energy solution for disaster victims or people in villages with minimal infrastructure. And in China, researchers have been looking at new types of carbon materials that could revolutionize the desalination industry by making the membranes that filter out salt radically more efficient. The challenge there is producing those materials at an industrial scale.

Regardless of future developments, California’s big move to desal is sure to be closely watched by other water districts in the United States that are looking at the economic costs and benefits of the strategy. When the Carlsbad plant is up and running, it will be selling its product to the San Diego Water Authority for more than $2,000 an acre foot — twice the cost of conventional water supply. (An acre foot is the amount of water, about 326,000 gallons, that it takes to cover an acre in water one foot deep. It’s enough to supply a typical family of five for a year.) The authority will be locked into buying at least 48,000 acre feet per year for the life of a 30-year contract.

The water from the Carlsbad plant won’t come close to slaking the region’s thirst, either. As Eric Holthaus recently pointed out on Slate, it will only fill 7 percent of San Diego’s needs once it starts operating, making recycled wastewater look like a more cost-effective (if initially less appetizing) prospect.

Proponents of conservation in California say that the state could still do a lot better on that front as well. As California’s water supply grows ever more precarious, water managers around the state will be forced to work harder to find solutions. Desalination may well emerge as a key component of the state’s water plan, especially if technological advances prove fruitful. Regardless of the environmental impacts or lack thereof, it will come at a cost that can be measured, painfully, in dollars and cents. Maybe that price will make consumers and water districts alike see conservation and recycled wastewater in a new light.

Sarah Goodyear has written about cities for a variety of publications, including CityLab, Grist and Streetsblog. She lives in Brooklyn.