The UN Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20 for short) kicks off this week in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Next American City will provide daily coverage of the summit by way of dispatches from Editor in Chief Diana Lind and correspondent Greg Scruggs.

The first day of Rio+20 arrived with the expected snarling traffic jams. The normal, brutal morning commute from the suburbs north of Rio de Janeiro into downtown and the beachfront was compounded by an influx of delegates, activists, journalists, indigenous chieftains — the whole panoply of characters that make for the world’s biggest environmental confab in the 20 years since Eco 92, the UN’s first earth summit in Rio, 20 years ago.

While stuck in traffic, the Rio+20 visitor — and likely the future soccer fan for the 2014 World Cup and spectator for the 2016 Summer Olympics — is spared the sight of the neighboring Maré favela, a vast complex of informal settlements that butts up against the highway. The transparent sound barriers put up a few years back, decorated with paintings by schoolchildren, now have opaque white boards pasted over them. The unsuspecting are completely unaware of the urban reality a few dozen yards beyond.

This kind of dissimulation is known in Portuguese as “para inglês ver” (for the English “to see”). The expression dates to a 19th-century anti-slavery law that was promulgated to make the English, who by then had abolished the slave trade, believe that Brazil was serious about ending it as well. They weren’t.

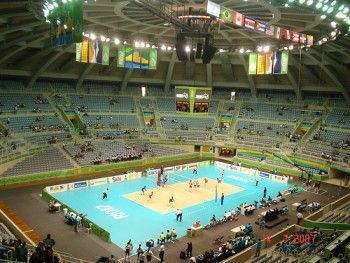

A venue for the 2016 Summer Olympics. Credit: Jorge Andrade on Flickr

The Marvelous City on the eve of Rio+20 is a bastion of efforts that seem largely for the English, or in this case the entire world, to see. But while foreign delegates are stuck in traffic and can’t see the Maré favela, the powers that be in the city have yet to figure out how to avoid what one can smell. Even with the windows rolled up, a putrid odor hangs along a several-mile stretch between the airport and downtown, wafting up from Guanabara Bay. At 159 miles, it’s the second-largest bay in Brazil, and it was at its mouth on January 1, 1502 that Portuguese sailors arrived to ultimately found the city of Rio de Janeiro (River of January, as at first they thought Guanabara was a river).

Guanabara Bay is still plenty picturesque at the mouth. It’s a narrow opening framed by verdant hills — most famously, a postcard image of Sugarloaf Mountain — that leads to the skylines of Rio and Niterói against yet more forest-carpeted mountains. It’s surely as impressive now as it was 510 years ago.

Unfortunately, the last century hasn’t been very kind to Guanabara Bay, which has become a combination sandlot and toilet bowl for metropolitan Rio. For starters, urban growth along the perimeter of the bay has destroyed much of the natural mangrove cover, a key buffer zone and habitat. The very highway that will carry delegates from the airport into the city is a 1980s-era landfill project, as are the domestic airport downtown and Flamengo Park, home to the People’s Summit.

Up until 1990, the teeming population at the Guanabara Bay’s edge dumped 490 tons of raw, untreated sewage (the size of Rio’s largest soccer stadium) into its waters. Nowadays, less than half of Rio’s sewage is treated, though the goal is to hit 65 percent by the Olympics. No surprise that the vast majority of bayside beaches have become too polluted for swimming, and even on the oceanfront, residents check the paper to see if their favorite beach, even top-billing Ipanema and Copacabana, is clean enough for a dip. After any significant rainfall, the answer is almost always no.

For those who live off the bay, life is increasingly tough as the fish yield drops. Brazilian news website Terra quotes a fisherman who has seen daily catches drop from 300 kilograms (660 pounds) to 30 kilograms (66 pounds). He attributes the situation as having gone from bad to worse since 2000, when a refinery belonging to Petrobrás, the state-owned oil company, sprang a leak to the tune of 1 million liters (264,000 gallons) of oil. Closer to Rio, Petrobrás maintains several platforms for training and maintenance in the bay, as well as major tankers in both the Rio and Niterói ports. Greenpeace’s good ship Rainbow Warrior sailed into Guanabara Bay yesterday and was swiftly given an official escort to allay fears it would blockade or otherwise protest Petrobrás facilities.

A slum near the Jardim Gramacho landfill. Credit: esquecidos.org

The Rainbow Warrior arrived otherwise unmolested, but the far more delicate sailboats competing for Olympic medals in 2016 have to contend with an unexpected obstacle: trash. Plastic bags are a more common sight than fish in Guanabara Bay, as the 19 rivers that feed into it carry untold quantities of litter. This includes everything from candy bar wrappers and PET plastic bottles to refrigerators and household appliances. The first major cleanup effort for the Guanabara Bay was launched, conveniently, at Eco 92, with little to show in the way of results and nearly $1 billion spent. In March, the Interamerican Development Bank signed another deal with Rio to pump $1.1 billion into cleanup efforts, with a focus on sewage treatment and trash collection.

Up until just two weeks ago, a likely culprit for the trash was Jardim Gramacho, the largest open-air landfill in South America that measured the size of 244 football fields. Haphazardly located on ecologically sensitive land at the bay’s edge in 1978, for nearly 40 years Gramacho has received the vast majority of metro Rio’s trash. And for just as long, that trash has been sifted through by catadores, waste-pickers who hunt down every last scrap of recyclable material and eek out a meager living on the proceeds.

The Gramacho catadores were made famous by the 2010 Oscar-nominated documentary Waste Land. Their thankless work — in Gramacho and countless landfills and city trashcans across the country — has made Brazil one of the world’s most prolific recyclers. This surprising statistic deserves plaudits, but also a fair dose of disapprobation toward a culture that assumes there’s no problem in littering, much less tossing all the garbage together, because someone will ultimately come along to pick it up.

For years, there has been talk of closing Gramacho and turning it into a biogas facility, capturing the methane produced by hundreds of thousands of tons of garbage. That day finally came in early June with a symbolic chain and a sign that says “trash prohibited.” The 1,603 people officially registered with the Jardim Gramacho Waste Pickers Cooperative will receive R$ 14,865 ($7,217 USD) each, to be paid by the company that will exploit the biogas. Registering so many informal workers and negotiating the payment was a gargantuan process that delayed the closure, but with Rio +20 nearing, it was an imperative to lock the gates by early June.

Pollution in Guanabara Bay. Credit: Angela Meurer on Flickr

Money in hand, many catadores interviewed by the media are unsure of their next steps. All they know is wastepicking, and the payments are not accompanied by any job training or education programs.

But the misery of Jardim Gramacho is a long way from the conference facilities that are hosting the international delegates and heads of state who have flown in for Rio +20. In a supreme irony, the UN Conference on Sustainable Development — in the broad sense of economic growth and social change in poor countries — is taking place in the least sustainable development — in the narrow sense of urban land use — in all of Rio.

The Barra da Tijuca neighborhood, originally laid out by architect and urban planner Lucio Costa, who designed much of the inhumanly scaled Brasília, is the 21st-century urban ideal that Rio’s power elite wish to show the world. That idea involves long stretches of unpolluted beachfront, verdant mountains unmarred by favelas, and a complete dependence on the automobile. Unlike most of Rio, Barra has shoulder room, with 64 square miles upon which to sprawl. And sprawl it does, with an ungainly assortment of massive gated condo complexes, car dealerships and shopping malls. It’s like the New York City Center, complete with a mock Statue of Liberty.

Since the 2007 Pan-American Games, there has been an ever-increasing focus on Barra as a venue for major events. Most prominently, the 2016 Olympic Park will be located in Barra. All the attention has made a mess of traffic into, out of and within the neighborhood. A subway extension to get people to Barra from downtown and the beachfront neighborhoods was supposed to have been ready for the Pan.

That never happened. Instead, Metrô Rio provided buses, called “Surface Metro,” that get caught in the same traffic jams as everyone else.

With the Olympics a make-or-break proposition, the subway is finally getting to Barra, but even then just so. The Alvorada terminal at the geographic crossroads of Barra is the logical place to connect the subway to three bus rapid transit lines that are the centerpiece of Rio’s new urban mobility strategy. Instead, the subway will stop just as soon as it can after the mountains. Passengers will then transfer to BRT for the less than four miles to the major hub, where they will have to transfer a second time to go to any Olympic facilities.

The first stretch of BRT was inaugurated just in time for Rio+20, another race-against-the-clock PR move that couldn’t be missed, with the mayor, the governor and even ex-president Lula on hand. Unfortunately, this stretch of BRT doesn’t serve any of the event spaces for Rio+20, which means conference goers will continue to rely on the city’s rickety fleet of buses or private shuttles provided by the conference, all sure to get sidelined in crawling traffic when official delegations roll through in lane-closing motorcades.

As public transportation makes its splashy debut in Barra, the real question is if it will peel Barra residents out of their cars. Given Rio’s spotty record with social mixing — elevator discrimination had to be prohibited by law — it is easy to be skeptical. Tourists and sports fans will likely rely on BRT during the Olympics. But for the rest of its useful life, will the system provide a more efficient means for the vast labor pool of maids, security guards and doormen that live in the working class neighborhoods beyond the Barra wonderland?

Certainly the lines that serve some of the more distant Olympic facilities need a hefty dose of transit-oriented development to justify their routes. On the flip side, the most heavily traveled road in Rio, the Avenida Brasil — which is a steady ant line of buses at rush hour — will likely be overloaded from the start with a projection of 900,000 daily passengers when the TransBrasil comes online.

In the meantime, a comprehensive, citywide BRT system is still a glimmer in natives’ eyes as they will sit through even longer commutes thanks to the added traffic of 50,000 Rio+20 visitors. Those without the luxury of a helicopter ride or police escort will likely be in the same boat, staring out the window at the lush hillsides of the Tijuca National Park, the world’s largest urban forest, and watching the floodlights turn on at dusk to illuminate Christ the Redeemer in an environmentally friendly shade of green.(The skyline icon has been lit green for the duration of Rio+20.) If only true urban sustainability in Rio were as simple as flicking a switch.

Gregory Scruggs is a Seattle-based independent journalist who writes about solutions for cities. He has covered major international forums on urbanization, climate change, and sustainable development where he has interviewed dozens of mayors and high-ranking officials in order to tell powerful stories about humanity’s urban future. He has reported at street level from more than two dozen countries on solutions to hot-button issues facing cities, from housing to transportation to civic engagement to social equity. In 2017, he won a United Nations Correspondents Association award for his coverage of global urbanization and the UN’s Habitat III summit on the future of cities. He is a member of the American Institute of Certified Planners.

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)