In San Diego, 325,000 tons of household trash will be collected this year. According to New York City, its residents generate 12,000 tons of waste each day. In 2012, the World Bank reported that “world cities generate about 1.3 billion tons of solid waste per year,” and estimated that figure would be 2.2 billion tons by 2025.

While cities around the world set goals regarding recycling and improving collection services, one group of artists in Mexico City looks at trash as an important agent in public space, and examines how it behaves and what it communicates. Driven by an archeologist’s lust for preservation and a collector’s passion for rare items, Tres Art Collective has spent seven years tracking, preserving, categorizing and exhibiting trash. Their work has allowed them to tap into the hidden logic of consumption and disposal in cities from Manchester, England, to Hong Kong, and with their latest project, the artists are following urban disposal all the way to the coastline.

For “Ubiquitous Trash,” the group is scavenging Western Australian beaches on a fellowship from Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. The project is based on the idea that trash has no clear border.

“Soda bottles made in China may wash up on a beach in Mexico or Australia,” according to an artists’ statement on the Tres website, “or, medical waste from New York may be found on the beaches of Brazil or Iceland.”

The insight came during a project in Manchester, England, in 2015, where they engaged with trash found in the Manchester and Pennine waterways. It was the first time the group worked with a body of water.

“Every object we find is produced in at least five different countries and distributed in many others,” says Ilana Boltvinik, a co-founder of Tres. “And then, when it is disposed, it travels again, through sea.”

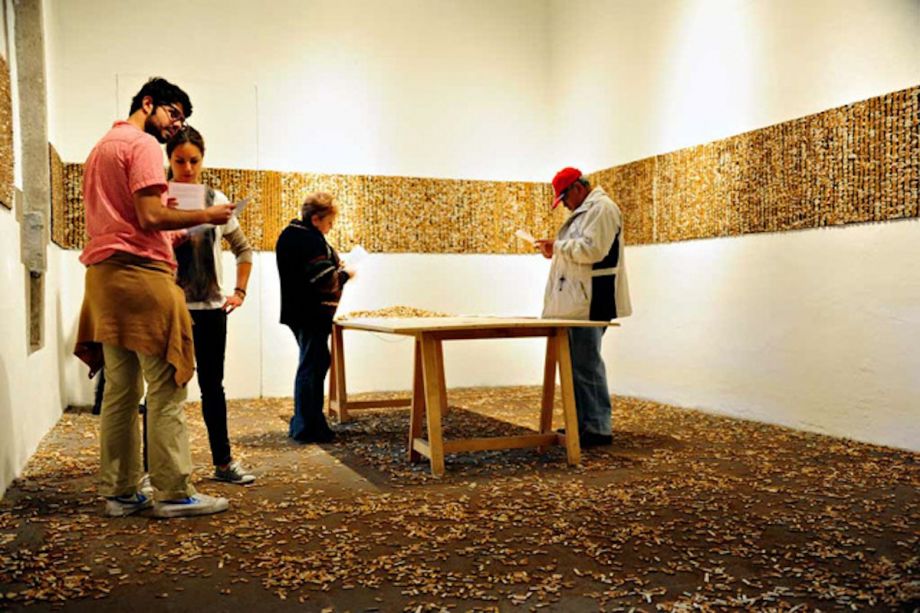

There has always been an element of shock in Tres’ exhibitions. For “Chicle y Pega,” they dressed in orange jumpsuits and worked on a stretch of sidewalk in downtown Mexico City to scrape up discarded chewing gum; the pieces were later shown in an art gallery. In “Huella Latente,” museum walls were covered with hundreds of thousands of cigarette butts. In “Transurification,” they displayed the distillation process of 80 different samples of urine, collected from plastic bottles around the city.

Tres Art Collective works on “Chicle y Pega.” (Credit: Tres Art Collective)

The work is highly political, says Boltvinik: “By bringing what is socially deemed as waste to public view, we are training citizens to look at these objects, and the social relations behind them, as valuable. ”

In other words, by seeing the way trash functions in the urban world, one also notices the human work needed to keep it out of view. There is a performative aspect of “scavenging” in a city center, Viñas thinks.

“In every city, trash collectors have a particular uniform and style, and the fact that we are the ones picking the items up, dressed in a different way, makes some people curious,” he says. “It changes our role and perception of the street.”

For the past few months, Tres members have been living in a camper and visiting Australia’s beaches, often under a blistering sun.

Their travel has allowed them to gain a glimpse into cultural differences, not only about how trash is managed, but also the perception of what is no longer deemed worthy of keeping.

“First-world countries are more wasteful,” Viñas says. “Here in Australia I’ve seen a drum set, computers and televisions in the garbage. This would never happen in Mexico.”

When asked if there are also commonalities, Boltvinik replies, “yes” immediately. “Plastic,” she says. “It is everywhere.”

Alan Grabinsky is a journalist and consultant based in Mexico City covering globalization, media and urban issues.