Earlier this week the Supreme Court voted 5-4 in favor of limiting state and local governments’ power to infringe on Second Amendment rights. The case, McDonald vs. Chicago, started as a lawsuit against the city of Chicago for their gun ban law, on the books since 1982. Otis McDonald lost his case locally, appealed to the 7th Circuit, lost, and appealed again. His case was merged with another similar suit against the city, by the NRA, and went to Washington. And it won.

The majority opinion ruled that under the due process clause of the 14th Amendment — which limits states’ ability to infringe on constitutional rights — any state and local law limiting Second Amendment rights is unconstitutional. Originally, the Bill of Rights only limited the federal government’s reach; the states could do as they pleased, more or less. We all know how this story ends.

Since Reconstruction, the Supreme Court has used the Due Process Clause to make the Bill of Rights applicable to the states, as well, limiting their powers, too. All of the protections in the Bill of Rights, except for the Seventh Amendment, and parts of the Fifth and Eighth, have been “incorporated against” the states. Since the Supreme Court set modern precedent for incorporating the Bill of Rights against the states in 1894, they had yet to hear a case for incorporating the Second Amendment, until now.

And now, any city (or state) that wants to impose any restriction on the right to bear arms will have no right to do so, because of a protection in the Constitution, which was written a good 40 years before Samuel Colt invented the revolver. The obvious problem here is that James Madison could hardly foresee the scourge of urban gun crime. When he wrote the amendment we were a new, agrarian nation, with an incredibly limited federal government, for obvious reasons. We needed the ability to defend ourselves, but did not want to create a large standing army. Also, the right to gun ownership was already common law at that point; the Second Amendment merely guaranteed that the federal government would not disarm any militias.

Now that we have a massive standing army, a national guard, local police forces, and all sorts of other professionally armed people to protect us, the notion that the federal government shouldn’t be able to disarm any militias is a bit antiquated. The Second Amendment is a protection that has become dangerously outdated, ironically, due to the growth of our federal government’s powers. It makes sense, then, that there is a great degree of overlap between gun rights activists and those who oppose government intervention in what they consider to be free markets. That this overlap occasionally manifests itself in the charmingly nostalgic gesture of raising a militia should come as no surprise, but certainly presents a tough PR challenge for the NRA.

But, one feature of these militias is that they tend to be raised in rural areas, where gun ownership also has practical applications, like hunting. The most fringe element of the gun rights debate comes from the parts of the country with a legitimate claim to the right to gun ownership. Any group of people in an urban area who get a lot of firearms together and plot to murder police might better be called a “gang.” Exercising your Second Amendment rights in a city is so vastly different from doing so in the sticks that it would seem there could be some argument to draw a modern distinction between the two, in the eye of the law.

That was the beauty of the Chicago gun ban; if you live in rural Illinois, and want to hunt squab in the summer, you’re free to do so. But if you live in Chicago, and want to keep a gun on you so that you might be able to murder a rival drug dealer, should the opportunity arise, you can’t. It was a city-wide solution to an urban problem, that did not infringe on the rights of other citizens of the state of Illinois.

But the central compromise to a city-wide gun ban — that one can still purchase and own guns elsewhere in the state — is what most likely also makes them somewhat ineffective. Washington D.C. also enacted a gun-ban, back in 1975, and didn’t manage to stop people from killing each other. Far from it. They were the murder capital of the nation back in the early 90’s, and as recently as 2007, their homicide rate was still more than double the national average for large cities. According to the Washington Post, it was not very difficult to get guns into the city from neighboring Maryland or Virginia. Chicago’s 2007 homicide rate was above the national average, too, but just by a little. On the bright side, perhaps, Sudhir Venkatesh — who you might remember from Freakonomics — conducted a study in Chicago, and found that illegal guns were quite expensive to buy, and difficult to come by. So while D.C.‘s might have failed, Chicago has at least made buying a gun somewhat difficult.

But taking questionably effective policy and making it unconstitutional because you think James Madison would have wanted it that way is an excellent example of why strict constructionism leads to terrible public policy. Because it’s trendy these days to trot out the living corpses of our Founders, I’d invite the reader to imagine walking with James Madison through East Baltimore, or some other down-and-out urban neighborhood, show him how a semiautomatic handgun works, and explain to him what hollow point bullets are, and how they’re different from musket balls. Then, for kicks, show him your new iPhone. No doubt, he would find all of this utterly bewildering, and that’s the point of this thought experiment. The structure of the Constitution aside, using the Due Process Clause to make city gun bans unconstitutional completely misses the point of the Second Amendment, and what the framers had in mind, at the time. It’s a shame Elana Kagan won’t be replacing one of the five justices who formed the majority opinion, should she be approved.

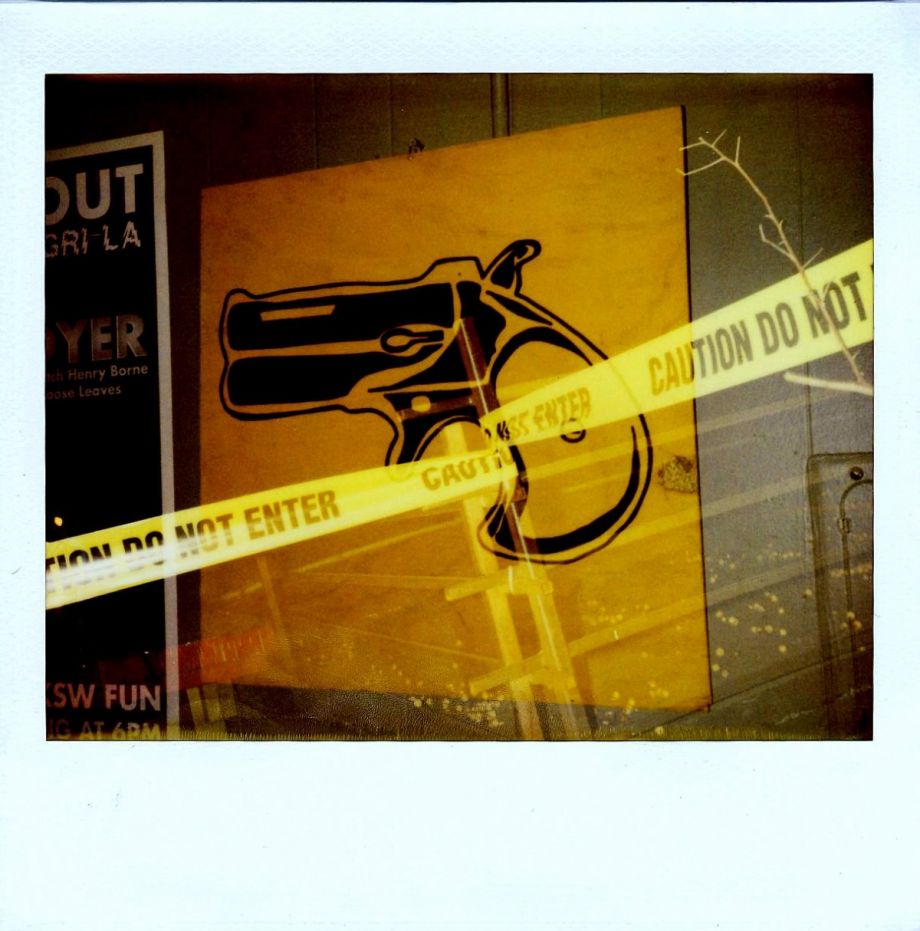

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)