One might think, given the hunger for good news about schools in cities like Chicago, that more people would have heard of Blaine Elementary. Since 2001, the percentage of low-income Blaine students doing well enough to have a shot at eventually making it to a four-year college has nearly tripled, from 8 percent to more than 23 percent. That’s not “mission accomplished” territory, obviously, but it’s pretty exciting in a city where the district-wide average, excluding test-in schools, is just over 5 percent. (By “on track for college,” I mean “scoring an Exceeds Standards on the ISAT,” the local standardized test. The ISAT, like all standardized tests, is a highly imperfect measure of educational quality, and the sun will rise in the east tomorrow. This is, however, the benchmark set by the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research, an organization that has at times been an outspoken critic of testing-driven reform.)

More remarkable, maybe, is that only a mile from Blaine is Audubon Elementary, where “exceeds” scores have increased from barely 1 percent to nearly 16 percent among low-income students over the same period. And then walking distance from Audubon is Burley, whose numbers have jumped from 4 percent to more than 19 percent. All told, there are 10 elementary schools, all clustered in the same region of the city, whose low-income students have collectively improved more than twice as fast as their peers in other public, non-selective Chicago elementaries.

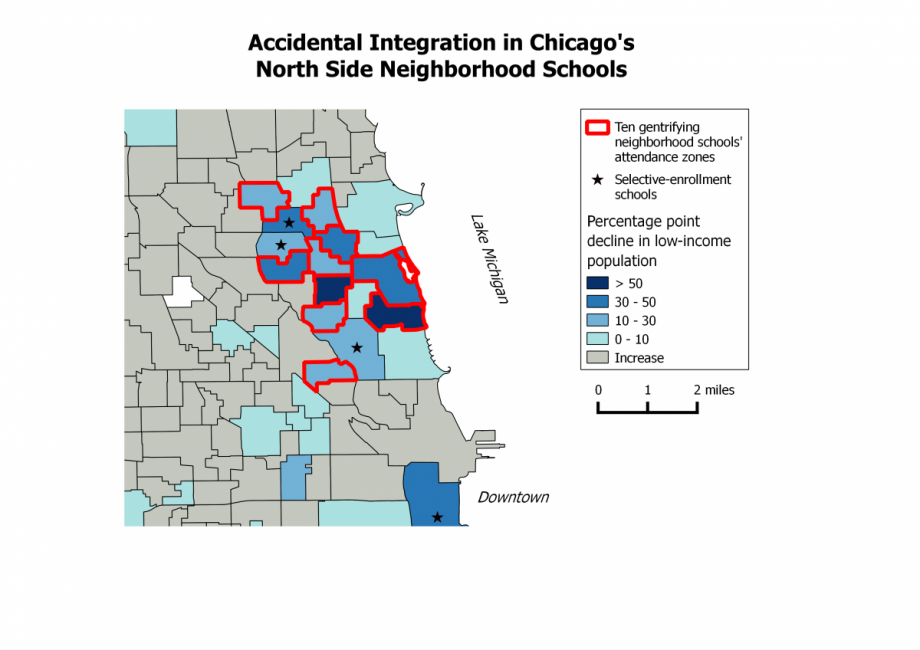

These schools aren’t charters, and they can’t screen incoming students — anyone who lives in their attendance boundaries gets to enroll. Instead, they’re the accidental, and possibly temporary, beneficiaries of intense pressures in Chicago’s housing market and test-in public schools: They integrated.

In Chicago, as elsewhere in the United States, that is a profoundly unusual thing for a school to do; in this case, it only happened under duress. For a very long time, virtually anyone with the ability to do so had kept their children out of Chicago’s neighborhood schools. If they didn’t move to the suburbs, they sprung for private school, or got lucky enough to receive an admissions letter from one of the city’s elite public test-in academies.

From the point of view of white-collar families, this multi-tiered system worked — until the number of white-collar families began to explode in the early 2000s. Applications to selective-enrollment elementaries soared; from 2008 to 2012 alone, they increased 50 percent. Although Chicago built some new selective-enrollment schools, it wasn’t nearly enough to keep up with the massive wave of demand for seats.

So the wave spilled over into neighborhood schools. In part, Chicago’s restrictive housing laws artificially inflated prices in gentrifying areas and rapidly turned once-blue-collar neighborhoods into mostly wealthy enclaves. By the year 2000, some schools with overwhelmingly low-income student bodies were sitting in communities where the median family’s income was twice as high as in the Chicago metro area as a whole. As a result, when local parents began organizing campaigns to increase nonpoor enrollment at their neighborhood schools, there was no shortage of eligible families to draw from.

The changes were dramatic. At the turn of the millennium, the 10 schools whose students have made such exceptional gains were, on average, nearly 90 percent low-income, just a bit less than the district as a whole. Since then, that number has fallen by 36 percentage points. At the same time, the average white enrollment has increased from 16 percent to 41 percent.

(Map by Daniel Hertz)

Test scores skyrocketed, and many of these schools have become the default for local middle- and upper-middle-class parents, who are more than happy not to have to jump through the city’s selective-enrollment hoops.

What makes this more than a simple story of educational gentrification is that everyone, not just the gentrifiers, appears to be benefiting. In addition to the rapid rise in low-income students’ test scores, “exceed” scores increased more than twice as fast as in the district as a whole among black and Latino students. (Though those scores remain dismally low, at 6.6 percent and 12.4 percent, respectively.)

That shouldn’t actually be a surprise. Despite all the attention given to reform, charters and new teaching strategies at the nation’s racially and economically segregated schools (the ones that are black, brown or poor, that is; the nation’s segregated white and affluent schools are doing great already), research has shown for some time that one of the most reliable ways to improve academic performance among students who are on the wrong side of the “achievement gap” is to desegregate them. The effect actually appears to be stronger even than funding: In one study, poor students who attended a mixed-income school did better than poor students who attended a segregated school, even when the segregated school received more money per pupil.

The situation in Chicago, of course, is not perfect. Test scores — which, however flawed they might be, have real impacts on students’ lives — are still too low, and still show a large gap between these schools’ low-income and non-white students and their more privileged peers. It’s also hard to know exactly how comparable, say, a school’s low-income students in 2013 are to a cohort from several years prior, or if there are other hidden demographic changes that might partially explain the rise in test scores. And as of yet, gentrification has yet to reach any of the city’s neighborhood high schools; the transition may, for any number of reasons, be bumpier there.

But Chicago’s accidental experiment with integration might still be its most promising educational reform in recent memory. What is especially promising is that the affected schools have hardly turned into walled fortresses of privilege: On average, the 10 schools are still more than 50 percent low-income, and nearly 60 percent non-white. That’s been sufficient to see rapid, ongoing test score gains, and keep local white, middle-class families happy with their neighborhood public school.

The question, of course, is how long that can last. “With the gentrification, even people I know have gotten squeezed out,” says Rebecca Labowitz, who has navigated Chicago’s gentrifying elementary schools as a parent and has become one of the city’s closest observers of the educational landscape on the North Side. Her long-running blog, CPS Obsessed, is both a clearinghouse of information and a gathering place for parents trying to squeeze as much education as they can out of the city’s public schools; many of them are middle-class or well-to-do newcomers.

Of course, the addition of high-performing neighborhood schools to already desirable neighborhoods is only likely to intensify that process. If current trends continue, the schools may not be so diverse by the time today’s kindergartners have their eighth-grade graduation. And if that’s the case, there won’t be many traditionally underserved students around to reap the benefits of these newly high-performing schools.

With that moment rapidly approaching, it’s up to CPS to decide what — if anything — the city’s educational apparatus wants to do to maintain this accidental integration, and the academic benefits it’s created. For their part, Labowitz says many gentrifying parents have mixed feelings about their schools’ diversity. Many “want to have diversity, that’s why they’re in the city.” But there’s apprehension about who, exactly, their children share a classroom with; Labowitz says that the reputation of nearby elementary schools serving children from the Cabrini Green public housing project led many parents to oppose the possibility of moving some students there from an overcrowded, gentrified elementary school just a mile away.

And support from those families will likely be crucial for any kind of attempt at integration. This is especially true because, Labowitz says, these parents tend to be much more aggressive at lobbying teachers and administration, often leaving other families, “especially immigrant or non-English speaking, feel unwelcome.”

Given that today, nearly nine out of 10 students in Chicago’s public schools are considered low-income, the current potential for integration is clearly pretty limited. (At least, that is, until Milliken v. Bradley gets overturned.) But if these schools are a harbinger for others in gentrifying neighborhoods across the city — and there is evidence that that’s the case — then a time may come when CPS has the option, however politically fraught, of attempting to make a substantial number of desegregated schools a permanent reality in Chicago.

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Daniel Kay Hertz is a student at the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy. He writes at danielkayhertz.com.