Rotterdam is selling its water. Or, to be more precise, it is selling a 30-year concession on 21 hectares of quiet water in the Rijnhaven area on the Maas River. Why would developers possibly want to buy a chunk of this giant stagnant bathtub? For starters, so they can build a floating city.

Framed by the up-and-coming Katendrecht neighborhood and the densely skyscrapered Wilheminakade, the Rijnhaven waterfront is a somewhat incoherent mix of former port industries, commercial areas and grassroots initiatives like pop-up homemade markets and a neighborhood theater. Just 30 years ago, this area was the most notorious neighborhood in Rotterdam. Situated along a man-made peninsula stretching into the Maas River, the Rijnhaven and adjoining Katendrecht district were given over to every kind of vice. Before World War 2, the largest Chinatown in Europe was located here. Immigrants lived in tenement-style housing and opium abuse was rampant. When a citywide bordello ban went into effect in 1911, all the prostitutes were moved to Katendrecht – the one “exception area” carved out in the city. The fact that the peninsula could be sealed off, if needed, was one of the government’s main arguments for the move. As a recreational destination for sailors during and after the war, these neighborhoods were rife with legal prostitution and sex clubs until the early 1980s. As time passed, the concentration effect slowly led to more violent crime until Katendrecht and the Rijnhaven eventually became a no-go zone for most Rotterdammers.

Today, a leisurely walk along the Rijnhaven waterfront reveals almost nothing of its salacious past. Young families stroll by, organic food festivals invade the public spaces and the former industrial warehouses are slated for redevelopment as posh riverfront apartments. The old residents are nowhere to be seen, and Katendrecht has recently become one of the trendiest residential addresses in the city. With the new pedestrian Rijnhaven Bridge making access to the Wilheminakade more convenient than ever, the Rijnhaven water itself has now been pinpointed for redevelopment. But how to approach this area? A preliminary development plan for the Rijnhaven was initiated in 2008, but it wasn’t until 2012 that the Rijnhaven project really took off.

For the municipality, the intention is to realize innovative answers to ongoing delta challenges. One way of doing this is the production of floating urban forms. But how do you make a city float? To be honest, the Rotterdam municipality has no idea. But they have the ambition. To make this concept a reality, they’ve opened the Rijnhaven to private tenders. In a startlingly honest introduction to the bid book, the city makes no bones about their role in this groundbreaking approach:

“A new type of area development requires a new definition of the public sector’s role. As the harbour’s owner, the city does not bring a fully developed plan to the table. We won’t be bringing a sum of money to the table either. This is a radical shift compared to the traditional client-supplier model. The current economic situation forces all parties involved to fundamentally rethink their roles. Old business models will need to be replaced with new ones. The way we invest in new activities shall continuously adapt to the changing developments. Each of us, whether public or private, will need to ask ourselves new questions, to find new answers and to forge new types of collaboration.”

Jorge Bakker’s “Floating Forest.”

As alderman in charge of the project, Hamit Karakus explains the reasoning behind this unusual strategy: “With regard to Rijnhaven, we have chosen a different approach. First, the municipality indicates which social benefits they would like to have realized within a small and clear set of preconditions, without determining the project. The next step is to take the request to the market and to look for the party that may realize the social benefits in the best possible way. By adopting this course, the municipality opens the door to market ideas. This means that the municipality asks market parties to pull out all the stops to put this part of Rotterdam on the world map.”

The project is currently in the tendering stage and it is clear that Rotterdam is keen to use the Rijnhaven as a showcase for cutting-edge harbor redevelopment. To this end, they’ve established a number of ambitions that potential partners for the development will have to support. According to a press release, the project’s stated goals are: “Metropolitan delta innovation; Quality of Life improvement; Waterfront development and Sustained Shared Value Creation.” In the recently published bid book, the city makes it clear that whichever consortium wins the contract will be expected to develop a vision in line with these expectations.

After a first-phase selection of three potential proposals, the city government expects to complete the final selection before the end of 2014. The three semi-final proposals will be made public after they are selected by an international committee led by former minister of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment, Pieter Winsemius. Other members of the committee include Astrid Sanson, director of urban quality for the municipality; Arnold Reijndorp, urban sociologist and professor at the University of Amsterdam; Jan Rotmans, professor of transition management at Erasmus University; cradle-to-cradle scientist Michel Braungart; former mayor of Antwerp Patrick Janssens; and Spanish architect and urban planner Joan Busquets. The final selection will be made after a series of dialogues between the applicants, the city of Rotterdam, the Port Authority and other specialists.

For now, temporary initiatives like the “Floating Forest” (Dobberende Bos), an art installation conceived by Jorge Bakker, will keep the Rijnhaven in the public eye. In Bakker’s installation, 20 trees drift majestically through the water, suggesting questions about how city dwellers relate to nature and ideas about “manufactured” natural environments.

Complimenting whatever floating form eventually fills the Rijnhaven will be a series of private developments along the southern waterfront. Plans for the massive new European China Center make sense here, recalling the area’s history as a former Chinatown. The 100,000-square-meter development will include apartments, a hotel, offices, restaurants, an Asian supermarket, Chinese shops and conference spaces, as well as a huge Chinese garden in the central atrium.

Pieter Kromwijk’s floating Autark Home, via YouTube

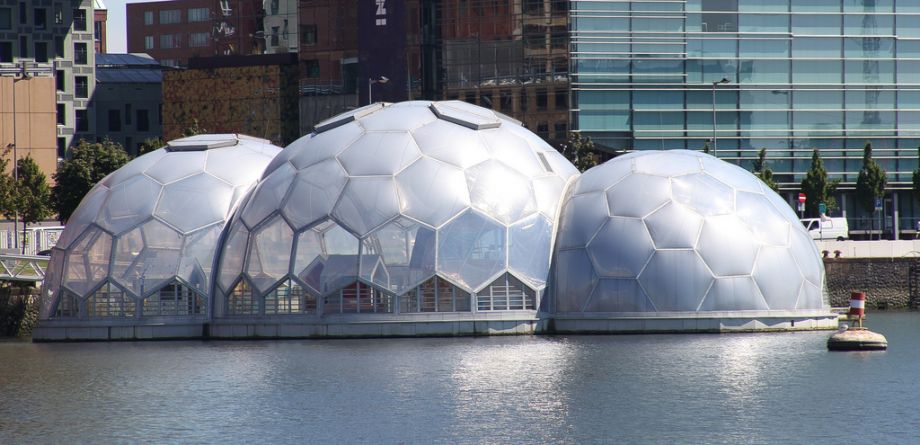

The Fenixloodsen, two former industrial warehouses along the waterfront, are currently being renovated by Mei Architects into terraced mixed-use buildings with 230 apartments, restaurants, offices and shops. And the Floating Pavilion has been bobbing in the Rijnhaven since the summer of 2010. It was constructed partly as a test case to see if this scenario was feasible. Its popularity has proven, albeit at a much smaller scale, that there is real potential for this kind of development in the Rijnhaven context. Temporarily moored next to the Floating Pavilion is architect Pieter Kromwijk’s Autark Home the floating model house is completely passive and self-sustaining — and perhaps a harbinger of things to come for this quiet harbor.

With its long history as a port city, it’s understandable that Rotterdam turned its back on the Maas River. Industrial pollution and a rough-and-tumble reputation kept people away. Even the river itself was dangerous, sometimes presenting an uncontrollable threat. Now, however, it seems this city is slowly awakening to the potential presented by it. As Rotterdam prepares for a difficult future, the relationship between this city and the river that flows through her heart is becoming a search for alternatives that will bring out the best in both. Instead of barricading itself behind higher and higher dikes, Rotterdam is looking for scenarios that will allow it to grow and adapt to the unpredictable effects of climate change. For this city, that might mean an entirely new way of living with water. In the Rijnhaven, it will certainly mean living directly on the water, instead of in fear of it.

_1200_700_s_c1_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)