For intercity travelers across the Northeastern U.S., Fung Wah evokes far more than its direct translation, “a magnificent wind.” The original carrier in the now mammoth network of Chinatown bus companies that serves 5 million passengers annually, the Fung Wah bus is a cultural icon, the eponym for an entire industry of budget travel. Last week, it ascended to even loftier heights in the urban imaginary, taking its place among the upper crust of the art world. How? It got its own biennial.

The Fung Wah Biennial fittingly touts humbler beginnings than its counterpart in Venice. The month-long exhibition was commissioned by Queens-based artist collective Flux Factory “as a celebration of the multicultural, economical and infrastructural reality introduced and fostered by Chinatown bus lines.” It loads over 20 artworks in a range of media and passengers onto three “galleries traveling at 70 miles per hour” — organizer Will Owen’s preferred description for the Chinatown buses that are traveling from New York to Boston, Philadelphia and Baltimore on three Saturdays this month. (Post-trip documentation of the works will be on show in a more traditional gallery.)

Fung Wah, of course, isn’t operating these buses. The company shuttered in 2015 after nearly 20 years in operation — a casualty of a regulatory crackdown on buses deemed too dangerous after a series of highly publicized crashes and incidents plagued numerous lines. (Whether the risk is greater than comparable services is, however, contested.)

As I boarded the chosen Fung Wah substitute last Saturday for the first biennial trip to Boston, I wondered whether I’d find an artful experiment truly celebrating the Chinatown bus, or another installment in a long lineage of non-Asian passengers coveting the experience for its foreignness. A 2012 study of Chinatown bus riders found that “participants routinely framed the Chinatown bus as an authentic urban experience, a thrilling and danger-enhanced departure from daily life, and as an engagement with the multicultural city.” In other words, many passengers are after an encounter with the “other,” as much as the low price point.

While Chinatown buses are notable for their racial diversity, especially compared to corporate curbside competitors like Megabus or BoltBus, the faces on my trip were whiter than the norm. There were no immigrant job seekers en route from an employment agency to their new gigs at Chinese restaurants along the highway. Despite efforts by organizers to attract non-art seekers to the chartered ride through postings on Craigslist, only two passengers boarded with pure travel intentions. This was, in a sense, an unauthentic Chinatown bus journey, and it was assuredly a nontraditional one.

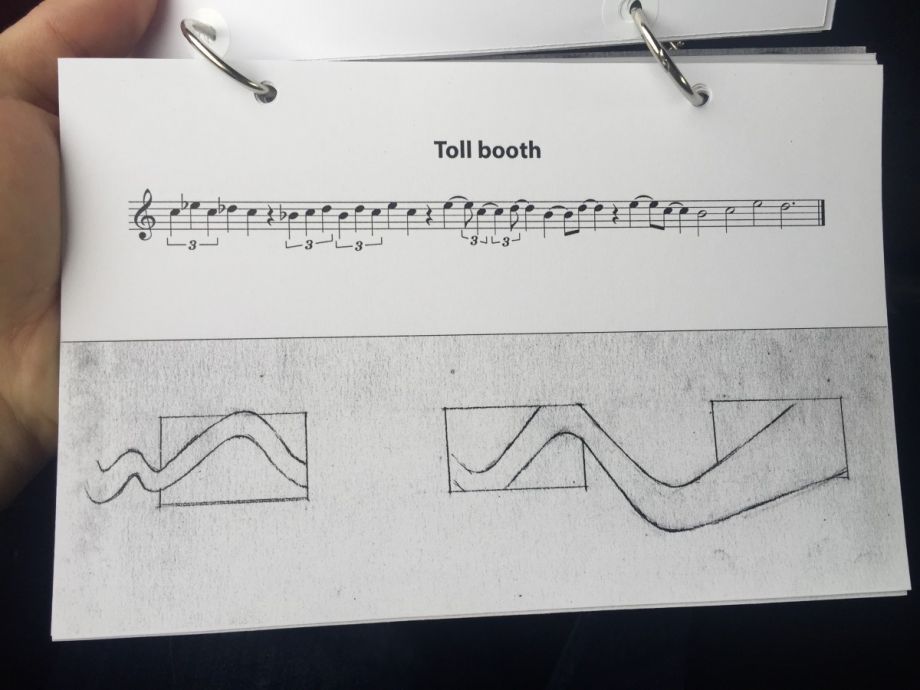

As we passed through the Bronx, a man one row up played a short phrase on his melodica, with mandolin and a faint flute chiming in from across the bus. Alex Nathanson, one half of Fan Letters, the group behind the periodic soundtrack, noticed my craning and shared a selection of the environmental cues that would provoke future musical bursts: Highway Split, Toll Booth, State Line, Big Box Store, Pothole (Seen or Run Over).

(Photo by Jonathan Tarleton)

“We were interested in the subjective experience of being on the bus,” Nathanson explained. Cues might never appear or go unseen, like the Bird of Prey that evaded one musician. Or, said Nathanson, “when we give everyone a cue for the moment we leave New York, that could mean many things; it’s really personal.”

The buzzing of incoming text messages joined the chorus. On all participating phones, a conversation between Ariel Abrahams and Rony Efrat covered everything from the nature of feeling alone to living room fort construction — the kind of personal, often unintelligible, and mundane conversations overheard as people carry on in transit.

The implied intimacy turned physical hours later. A woman crawled over each pair of seats filled with unsuspecting passengers in a full bus circumnavigation, head arched backward and arms outstretched. This was, as the artist Sunita Prasad explained to me, one piece in a larger body of work evoking “the tension of threat and trust that we experience with strangers in public space.”

The dearth of true strangers on the journey cut the power of the act, but far more refreshingly absent from Prasad’s crawl and the larger biennial was the kind of fetishization that often plagues the cultural role of the Chinatown bus.

A serial play unfolded under a mini proscenium. An onboard travel agent calculated my adventure aptitude assessment matrix. A man in a white suit held his herb-garden-in-a-suitcase close.

Against these artistic interpretations of the personal and interpersonal possibilities inherent in a transportation mode marked by accessibility, diversity and close quarters, the Chinatown bus looked downright ordinary. I asked the driver, on his smoke break at the Connecticut line on the return, what he thought of the whole operation. I got a look of confusion and no reply. The biennial may traffic in the icon of Fung Wah — its cheap thrills, sometimes with no English included — but what came through on the other side is its commonplace reality.

The more than 400 buses arriving in and departing from Manhattan daily form an extraordinary and vital network of vessels, rich with possibility for the passengers within. Otherwise, they chug along, an accessible infrastructure of everyday effectiveness.

The Fung Wah Biennial bus will run from NYC to Philadelphia on March 12, and to Baltimore on March 19. For event information, see Flux Factory’s site.

Jonathan Tarleton is a writer, oral historian and urbanist based in Brooklyn. He is chief researcher and a contributor for Nonstop Metropolis: A New York City Atlas and the former editor of the magazine Urban Omnibus.