Maya Angelou’s death this past May turned my Facebook feed into a memorial service. People put up old photos. They shared deeply personal journal entries. It was a fascinating mix of spectacle and sincerity. Lots of people I knew had met her and perhaps shared a moment with her at some point in their lives, and it had meant something. Somehow it had changed them. She was a folk figure in the purest sense — no matter how she soared, she was always one of the people.

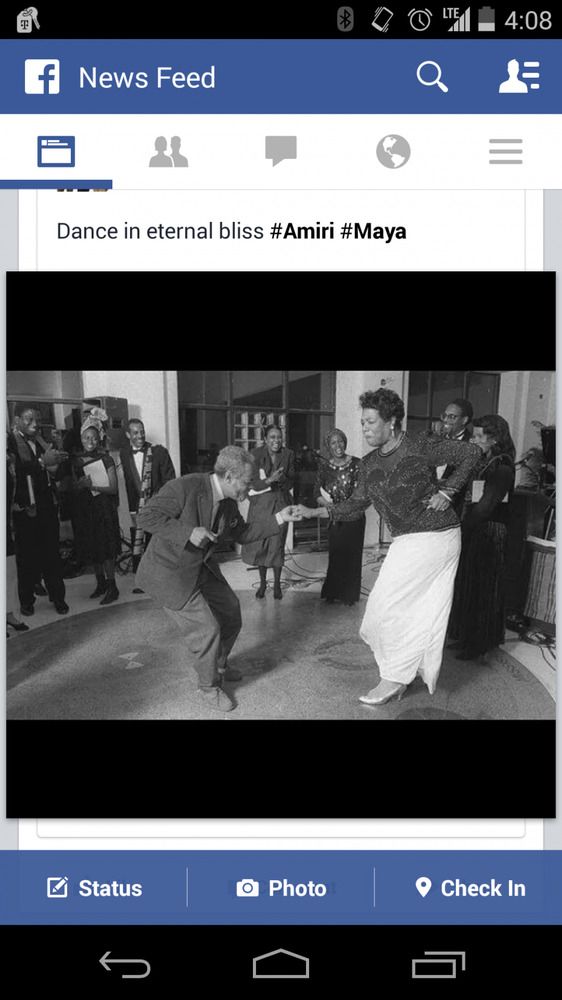

I had a similar feeling toward the late poet Amiri Baraka. I was reminded of this when a photo of them together surfaced amid the memorializing. It’s a perfectly timed, timeless moment: a pair of 20th-century literary icons suspended eternally in their prime on a dance floor, lost in song.

The writer’s Facebook feed

But while in life, Baraka and Angelou were literary peers and comrades in struggle, in death, they’ve not shared similar fates. Angelou owns a first-class ticket to the canon. Baraka is on standby. He didn’t have an I Know Why the Cage Bird Sings. He made his living courting racial controversy and critiquing capitalism.

But even if you didn’t dig Baraka’s art or his politics, you had to respect his body of work. As a writer, he did it all: poetry, drama, fiction, screenplays, journalism, history, essay, biography. In a single lifetime he was the lone black Beat, the primary architect of the Black Arts movement, a lecturer at several of America’s leading universities, a leading Black Power figure and a Marxist. And — as of this past May — you can add parent of a Newark mayor to that list.

I first encountered “Mr. B” back when I was a student at Rutgers. At least twice a year, one student group or another brought him to campus to read or lecture. The same hundred or so of us, packed into whichever student center he was speaking in, would sit like wide-eyed acolytes waiting for him to arrive. Invariably he’d scuttle into the room and directly up to the podium, late but not disrespectfully so, wearing a tweedish cap and blazer, round spectacles and that scraggy gray beard. He’d carry the stack of books and papers he planned to read from beneath his arm like a stolen loaf of bread. He had a slight stoop and a way of peering out at us with one arched eyebrow that always seemed to beg the same question: “What the hell are YOU doing with your life?”

Then he’d press his eyes shut and start pounding his fist on the lectern like he was summoning the ancestors. Suddenly he was elsewhere or we’d disappeared. Mr. B’d seamlessly bound from a scat, to an elegy to prose to a wry polemic about the most recent global atrocity he felt worthy of our attention right back into bee-bop-cadenced verse. His mind was a map of the African diaspora. Mr. B hipped us to the likes of Franz Fanon, Alexandre Dumas, Aimee Cesaire, Amilcar Cabral, CLR James and Patrice Lumumba, names we’d never heard and wouldn’t have heard in our classes. Ironically, the Rutgers English department, citing his shortage of scholarship — so I was told by another professor — had denied him tenure a few years before my arrival.

When the reading was all over, Mr. B would gather his papers and books and hurry off the stage. I sometimes wondered what it was like for him to remain so connected to the school that rejected him.It was after one of these campus performances that I gathered the nerve to introduce myself. I told him I wanted to be a writer and he looked right through me. Mr. B was polite enough, but I could tell he wasn’t impressed. He’d heard too many of my predecessors issue the same brave announcement. How many of them had he watched march out of college and into law school?

Over the next couple of years, I found myself spending time at the Baraka home in Newark. A small group of us would drive up from New Brunswick on Friday evenings to listen to Ras, their eldest son (and Newark’s newest mayor), deliver his weekly “State of Newark” address in the basement. We were self-styled activists and artists in our early 20s, and Ras was our exhorter. He would sit in the front of the room and break down the latest chapter of The Wretched of the Earth like it was basic arithmetic. He wasn’t the scholar that his father was, but he had the same speechifying gift and a similarly arched eyebrow that shot daggers into your conscience if you hadn’t completed the reading. We didn’t just read down there, though. We’d plan clothing drives, neighborhood clean-ups and campaigns against police brutality. It may have been the ‘90s, but those nights felt every bit like being in the movement. There was no other place I wanted to be on a Friday night and, for me, Ras played a large part in that.

On one of those nights, I wandered upstairs to the use the bathroom and found Mr. B sitting at the dining room table by himself. He and his wife, Amina, maintained an informal open-door policy for young people looking for direction. I told him I was taking the LSAT the following morning, and that I felt like I was giving up without trying to live out the ideals. Really, I wanted, and maybe even expected, him to talk me out of taking the exam.

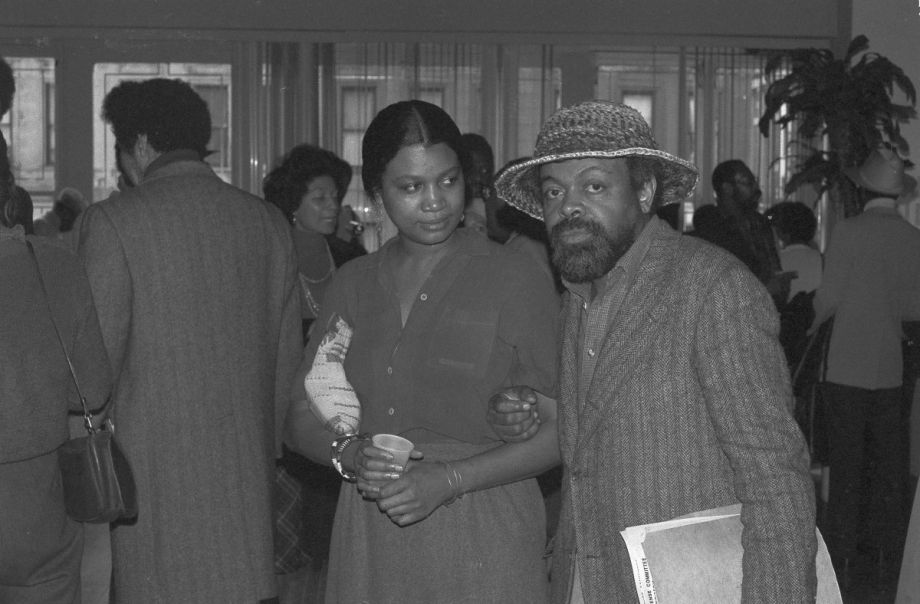

Amiri Baraka with his wife, Amina, during a party for Dizzy Gillespie in Harlem in 1980. (AP Photo/Burley)

I didn’t see Mr. B again until I moved to New York to pursue my own career as a writer after law school. In the interim, he’d been appointed poet laureate of New Jersey. It looked as though he was finally ready to assume his rightful place as a national (or at least Garden State) treasure. Likewise, the mainstream seemed ready to let bygones be bygones and invite him into the canon. Then 9/11 happened, and Mr. B wrote a poem called “Somebody Blew Up America”. It all but alleged that the Bush administration and Israel knew about the attacks ahead of time. I happened to be in the audience when he read it during a taping of the first season of Def Poetry Jam. A gasp shot through the audience when he was finished. Then came the strangest applause I’ve ever participated in. The country was still in the patriotic haze. The poem wasn’t going to air, but it was only a matter of time before less tolerant ears heard it. The applause seemed to convey “Godspeed.”

Sure enough, Mr. B read “Somebody” at Wellesley College later that fall and was accused of being anti-American and, for not the first time, anti-Semitic. When New Jersey couldn’t get him to relinquish his post, the state lawmakers abolished the poet laureate position entirely. At the very moment of his enshrinement, Mr. B cast himself out America’s good graces permanently. I’ve since often wondered if that was his intention.

Three or four years ago, I saw Mr. B standing on a platform at the World Trade Center PATH Station. It was late and he was standing alone like a regular bloke, which irritated me. Here was one of the most extraordinary living American writers, the very embodiment of an historical presence. Everyone should have known him. He should have received an impromptu ovation. Instead, they all just saw some geezer waiting for the train back to Newark.

I walked up to him and started talking. I didn’t remind him who I was. I just said “Hey, Mr. B,” which in itself was a signal, and we slipped into a perfectly casual conversation about the politics of the day that transitioned onto the train once it arrived. I got off before he did, though not without wishing him the best and thanking him for his efforts. That was the last time I ever saw him.

Baraka’s favorite allegory was the myth of Sisyphus. Having eluded Death, King Sisyphus is sentenced by the gods to carry a rock up a hill only to watch it roll back down at the end of each day as punishment. Albert Camus’ Sisyphus was a metaphor for the futile condition of the working man in the industrial economy. Baraka’s was a metaphor of the absurd situation black people in America found themselves in. Every advance begat a setback. He called it the “Sisyphus Syndrome.”

Newark Mayor Ras Baraka (AP Photo/Julio Cortez)

Meanwhile, Ras kept working in the community. He taught school and afterschool; he coached sports. He led one of the biggest and most challenging high schools in Newark. Eventually he was appointed deputy mayor, then won a seat on the city council. But he could never get over the hump. Even this time around, with Booker comfortably situated in the U.S. Senate, Ras faced stiff competition from another charming upstart, Shavar Jeffries. But four months after his father’s death, Ras was elected the new mayor of Newark after coming up short for 20 years.

Mayor Baraka has his work cut out for him. Booker brought a dazzle and cash to the city, but with his departure the boulder is back at the bottom of the hill. And inasmuch as Ras has announced, “We are the Mayor,” it’s on his shoulders to carry that stone back to the top. I can’t imagine the irony of his condition being lost on him or, if he were here, his father. But I also can’t imagine either of them begrudging his fate. How many people get the chance to restore their hometown and — maybe — restore their father’s name? Newark certainly has the tools: universities, hospitals, a major port, an international airport, cultural institutions, a major rail station, state-of-the-art sports facilities, highways, nearby suburbs, parks and, most importantly, people who love the city, blemishes and all.

“I leave Sisyphus at the foot of the mountain. One always finds one’s burden again,” Camus wrote at the conclusion of his allegory. “The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

Dax-Devlon Ross is the author of five books and has written essays and articles for a range of publications, including Time and the New York Times. He is a non-profit higher-education consultant and the executive director of After-School All-Stars NY-NJ. You can find him at daxdevlonross.com.