Implementing ambitious programs to promote sustainability can be tricky. Sometimes the long-term vision promoted by city planners clashes with the immediate needs of the people. For Medellín, this conflict is epitomized by plans for an elaborate “green belt,” a string of parks that aims to add green space to the city while simultaneously acting as a barrier to sprawl.

When the Cinturon Verde de Medellín (Medellín Green Belt) was officially inaugurated in December 2012, Colombia’s most popular national newspaper El Tiempo branded it “the most ambitious project of the (Medellín) Mayor’s Office.” Since renamed the Jardin Circunvalar de Medellín (Medellín Circumventing Garden), the project is intended to tame Medellín’s exponential growth, which has seen unplanned neighborhoods sprawl up the sides of the Aburrá Valley. In places, jumbles of ramshackle dwellings have already inched their way up to the valley’s ridge and the waterways running into the city. The green belt’s purpose is to shield the surrounding valley from such development and guard Medellín’s ecosystems and waterways.

“It’s fundamentally a planning strategy,” says Dora Beatriz Nieto, a senior architect at the Area Metropolitana del Valle de Aburrá, a public agency involved in the project. “The principal objective is the betterment of the quality of life for metropolitan citizens. It’s also orientated around consolidating the territory in a balanced and equitable way.”

According to Nieto, the importance of the green belt is not just in restraining unregulated growth, but also in the protection of water basins and forests, which help counteract the city’s chronic pollution, and stretches of countryside which are key to the region’s biodiversity.

It’s a sentiment echoed by Dr. Carlos Ignacio Uribe, the project’s manager for Empresa de Desarollo Urbano (Urban Development Company – EDU), the public entity responsible for the project. “This is a plan for sustainability and viability,” he says. “Given the landscape we have and the infrastructure we have, we cannot keep growing into the mountains. We have to place a limit on the city and that is what we are doing with the green belt.”

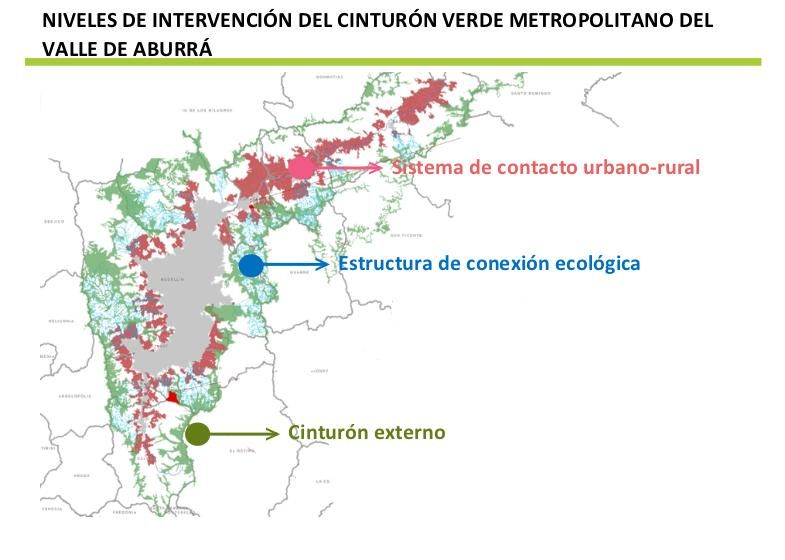

The green belt is divided into three distinct zones: a zone of protection (green), in which measures to preserve the natural habitat will be implemented; a zone of consolidation (blue) where peripheral settlements that have expanded beyond the city limits “require structural intervention,” according to Uribe; and a zone of transition (red), which has the highest concentration of residents living in conditions that often lack basic amenities and are spilling beyond the city limits.

But one year after the project’s establishment, the question of how it will manifest remains unanswered. El Tiempo highlighted the doubts swarming around the project at its initiation, many of which persist to this day. “It’s not a green belt, it’s a belt of questions,” says César Mendoza, a legal representative at human rights NGO Sumapaz Fundacion, which is working extensively with communities that will be affected by the scheme.

According to Mendoza, the people living in regions where rehousing or relocation is set to occur are still in the dark about their fate. How relocation away from unstable terrain will be managed and what form new housing will take is still unknown. Many are opposed to the idea of being evicted from the houses they built with their own hands and moved into city-built tower blocks.

As both Mendoza and Winston Gallego, the NGO’s human rights coordinator point out, many of those living at the city’s extremities are displaced people – victims of the country’s ongoing internal conflict who fled violence in the countryside. They’re new to the city and would struggle to adapt to the rapid, one-size-fits-all urbanization the scheme would create. “These buildings depersonalize people,” says Mendoza.

To Mendoza, the amount of money being proposed for a project that remains so undefined (the estimated total cost is a reported $260 million USD), as well as the inclusion of elements like a monorail, shows a lack of sensitivity to the affected communities, which feel the green belt is intended more for tourists than themselves.

“Where is the green belt in Poblado?” Mendoza asks, referring to Medellín’s most affluent district. “That [neighborhood] has gone beyond the city’s border, but they are not being moved.”

But most of all, the NGO is critical of the city’s sudden interest in the outlying communities, which were previously left to their own devices without access to most city services. “These are towns the people built,” says Mendoza, “and the city came later and told them how to live.”

While these concerns are certainly justified, it is clear that some kind of action is needed, not only to improve the living conditions of the most vulnerable and impoverished on the city’s outskirts, but also to manage the potentially destructive relationship between those communities and the ecosystems surrounding them. Whether the Medellín Green Belt is able to resolve the questions surrounding it and strike the balance necessary to meet those many competing needs as yet remains to be seen.