On a recent afternoon, the Second Street Tunnel in downtown Los Angeles was not jammed with noxious, idling cars. Instead, hundreds of bicyclists rode through, whooping and shouting to hear the acoustics of the gloriously free tunnel. They could enjoy the sounds without the congestion of cars because of CicLAvia, a wildly popular event where miles of streets are closed to cars for the day. People walked or pushed strollers along the tunnel’s sides, snapping photos of the more outlandishly decorated bikes and pedalers. At one end, musicians handed out xeroxed lyrics for a sing-along featuring songs about transportation. A group of paused walkers and bicyclists gathered around them, raucously yelling out the chorus to the early ‘80s song: “Nobody walks in L.A.!”

The words rang out against the stream of walkers and bikers, highlighting the current shift in how this city’s residents are thinking about transportation. Between 2000 and 2010, the number of Los Angeles residents who regularly commute by bike rose 56 percent. The total number of bicycle commuters is still less than two percent of the population, but vocal bicycle and pedestrian advocacy groups, 120 miles of bike lanes built in the past five years, and ten CicLAvia events since 2010, with five more planned for 2015, are helping change that.

Thousands of people participate in CicLAvia. (Photo credit:CicLAvia)

Later this week, six miles of Los Angeles streets will again be closed for the eleventh iteration of CicLAvia. It also marks the first time a CicLAvia is being held in South Los Angeles, a historically African-American neighborhood that is now about half Latino.

The South Los Angeles route will travel along Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard, a central thoroughfare and site of parades and protests. Riders will pass the historic jazz corridor of Central Avenue, the arts center of Leimert Park, and the gardens and museums of Exposition Park. Along the way, an eclectic selection of landmarks will be called out in CicLAvia’s free, pocket-sized brochure, such as the former headquarters of the Black Panther Party for Self Defense; the Aquarian bookshop, the oldest continually Black-owned bookstore in the nation (founded in 1941); and the Duke Brothers’ Car Shop, home of the largest and longest-running lowrider car club. Several hubs along the route will offer activities run by sponsors and partners, such as bike repairs, food trucks, health screenings, bike valet, live music, and kids’ workshops, while local businesses have been encouraged to set up sidewalk vending.

Since launching in 2010, each CicLAvia has been held in a different part of Los Angeles, opening up new areas to about 130,000 to 150,000 participants for the day’s events. This intentional perambulation encourages a mix of residents from the local neighborhood with those coming from all over the county and other nearby cities. As participants stray from their usual commutes, the imagined lines between neighborhoods soften. The city is experienced at a slower, smaller, more human scale that offers real possibilities for engagement.

“CicLAvia is not about celebrating itself; it’s about celebrating these streets and neighborhoods,” says Aaron Paley, co-founder and executive director of CicLAvia.

On a Stanton Fellowship in 2008, Paley visited Bogotá, where 75 miles of streets close down for bicyclists on a weekly basis. He met with Jaime Ortiz, who launched the Cicloviá (cycle way) program in the mid-1970s, creating a template that has now reached cities around the world. As Paley recalls, Ortiz emphasized how crucial it was for such events to be malleable and enable citizens to adopt it to their own needs.

In Los Angeles, no two CicLAvia’s have been the same—they seem to magnify the character and eclecticism of whatever street they overtake. Despite the emphasis on modes of transportation, Paley calls CicLAvia an “open space project” that aims to transform our streets so that they “function as living rooms instead of corridors.”

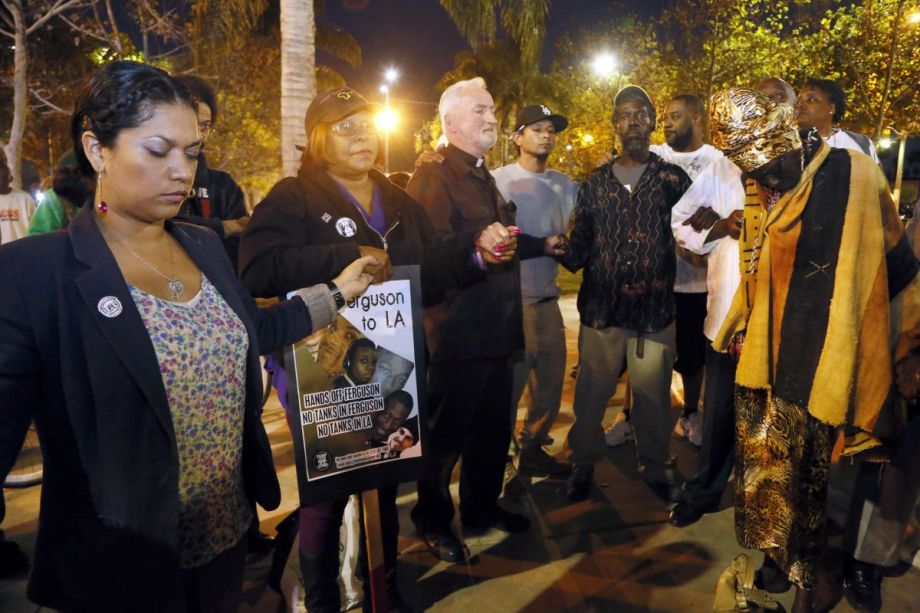

CicLAvia will descend on Leimert Park this weekend. Last week, peaceful demonstrators gathered there to protest a grand jury’s decision not to indict Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson in the fatal shooting of Michael Brown, an unarmed black 18-year-old. (AP Photo/Nick Ut)

Of course, creating a truly public living room, even for one day, invites differing perspectives. During October’s “Heart of L.A.” CicLAvia, part of the route ran through Boyle Heights, a Latino neighborhood now grappling with rising property values and displacement. In the weeks before the event, a few business owners voiced concerns that CicLAvia might make things worse. “First come the cyclists, then comes gentrification,” said art space co-owner Erendira Bernal in a radio interview.

“This has made us cognizant of how successful we have been and that our success brings other responsibilities,” Paley later told me. “If people can use CicLAvia to galvanize other issues, that’s a good thing.” Statistics on the participants in CicLAvia, or its economic impact, are not yet available, although a RAND survey conducted at last April’s CicLAvia revealed a racial diversity close to that of the city itself.

Elsewhere, cases of transportation strategies forced into areas without proper input from local stakeholders have resulted in backlashes, as seen in bicycle-infrastructure conflicts in Portland, Oregon and Washington, DC. While CicLAvia is trying to promote awareness about the possibilities and advantages of car-free mobility that might lead to civic adaptations, it is doing so through different means: inclusive, ephemeral, celebratory events that involve the local community and honor the historic and current spirit of diverse neighborhoods.

“We must always enable people to give feedback, and give them the feeling and reality of ownership to ensure that the character of the community is allowed to shine and is part of the event,” says Tafarai Bayne, a community organizer and native South Angeleno who has been instrumental in bringing CicLAvia to his region of the city. Noting the tensions inherent to any urban public space venture, he adds, “CicLAvia is fun and we’re just hangin’, but we’re also poking at equity, race, and class.”

CicLAvia staff and volunteers begin holding community meetings months or even years before a scheduled event. They post bilingual flyers, do social media outreach, and contact businesses along the proposed route multiple times to explain logistics and answer questions.

Vendors and artists play a big role in CicLAvia. (Photo credit:CicLAvia)

And then there’s knocking on doors. Bayne, who was inspired by attending the first CicLAvia in 2010 and later joined the organization’s board, gave me an estimate that he has personally talked to thousands of people face-to-face about the South Los Angeles route over the past few years. He has also organized meetings about pedestrian safety and infrastructure and ran community bike rides to gather ideas about what the route should include, to get people “more grounded and connected to their urban space.”

“South L.A. has a bad reputation,” Bayne says. “I’m excited for the opportunity for it to showcase itself and what’s actually really cool about the neighborhood. People here don’t bite.”

Paley notes that the popularity of CicLAvia and the demand for more of them all over the greater Los Angeles area signals a real shift in what residents expect of their city. “We have spent a very long time on a different paradigm: emphasizing private space at the expense of public space; private over public transportation; single-family homes vs. other kinds of living.”

“CicLAvia just answered a basic longing that was lacking in people’s lives,” he notes. “We have pivoted. We’re voting with our feet.”

The column, In Public, is made possible with the support of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

Lyra Kilston is a writer and 4th-generation Angeleno. Her writing has appeared in Artforum, Los Angeles Review of Books, Time, and Wired, among other publications.

_920_518_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)