Bongani Dube doesn’t care about recycling. All he cares about is his ability to hustle each and every day to earn enough money to feed himself. “On a good day I can make R150 ($15), on a bad day, R30.” he says.

The diminutive 23-year-old Zimbabwean immigrant is one of hundreds of waste-pickers in Durban. He’s lived on the streets here since he arrived in the city three years ago. Discarded supermarket packing boxes, empty cigarette cartons and other items cast aside by Durban’s better-off residents have kept him alive in that time.

But though it may not concern him, Dube is a critical player in a forward-thinking collaboration between Durban’s municipal waste system and the city’s informal recyclers. While other cities have embroiled themselves in conflict with their waste-pickers – declaring their efforts illegal and pushing for full formalization of trash collection – Durban has actively worked to incorporate workers like Dube into its overall waste-management strategy.

“If we didn’t have the waste pickers our drains would be clogged and the streets would flood whenever it rained,” says senior Durban city official Hoosen Moola.

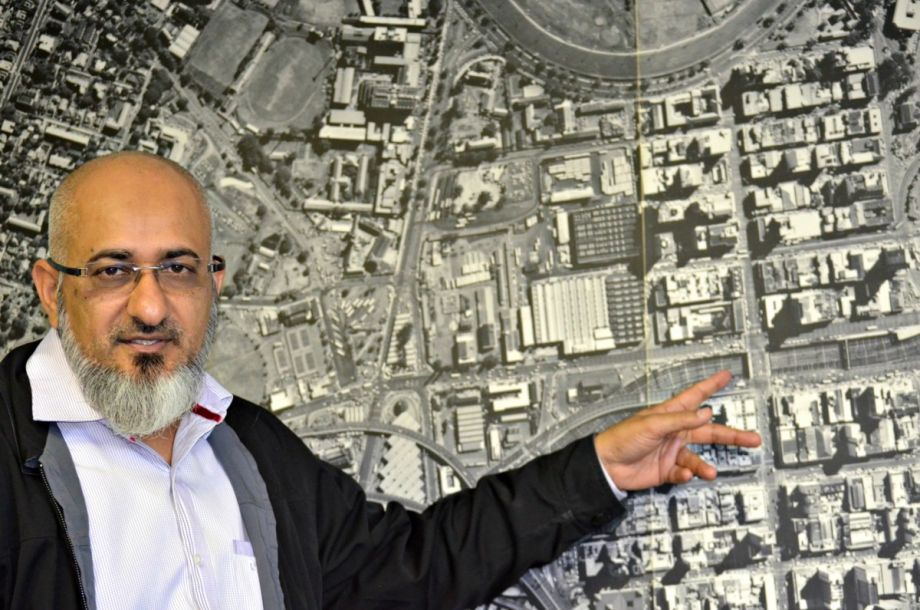

Moola is the head of iTrump, the Inner Ethekwini Regeneration and Urban Management Program, a position he’s held for the last six years. iTrump was originally founded to stem urban decay, but has since morphed into a supercharged clean-up unit that has done wonders in its work around keeping Durban livable. As head of the interdepartmental program, the soft-spoken Moola connects with a range of city agencies, including police, health, solid waste, water, electricity, architecture, roads and business support.

“We have integrated management meetings monthly. We identify the pressing issues and work together to fix them,” he says. “Sometimes this means teams working through the night with police and the solid waste department.”

Hoosen Moola, the head of iTrump.

For instance, Warwick Junction, where Moola’s office is, is a throbbing inner-city node and a nexus of rail, road and pedestrian traffic. An estimated 600,000 of the city’s four million residents pass through Warwick every day. Vendors hock cheap Chinese cell phones, corn on the cob, fresh produce, boiled bovine heads and traditional medicines. Shoppers discard plastic packaging on the ground. Street food piles up. It all ends up in the city’s drains, says Moola – if it’s not bovine-head cookers discarding chunks of meat, it the taxis being serviced on the roadside, dumping their oil onto the ground.

Under Moola’s direction, municipal staff have pulled sheep’s heads, building rubble and even fetuses out of the city’s drains as part of the iTrump program. They make sure streets are clean enough to attract foot traffic and keep business activity viable. “In some areas people defecate and urinate on the pavements,” he says. “We take to hot spots with high-pressure hoses once we’ve swept.”

But the iTrump program’s most progressive efforts revolve around incorporating waste-pickers into its work – indeed, Moola says the city’s waste-pickers are an essential component of Durban’s efforts to stay on top of the mess. Durban actively encourages the waste-pickers to participate in the system with two city-run waste buy-back centers in Warwick Junction. At these two centers alone, 189 tons of cardboard and paper is recovered every month. All in all, eThekwini is able to divert eight percent of total waste from landfills. Moola believes smart organization, regular clean-ups and tolerance for everybody’s need to make a living enables iTrump to keep Durban’s clogging with junk. “Large numbers of people will obviously put a strain on infrastructure,” he says, “but if we work together and understand that everyone, including the waste-pickers, is trying to survive, then we get along fine.”

This strategy will only become more crucial to South Africa in the coming years. According to the 2012 National Waste Baseline report, South Africa as a whole generated approximately 108 million tons of waste in 2011. At a recent meeting conducted by the country’s Institute of Waste Management, environmental consultants Jeffares & Green said this volume of waste is expected to double by 2025.

According to Richard Dobson, who helped launch iTrump and now works for Asiye eTafuleni, a non-governmental agency that has worked to help waste-pickers and others in the informal economy, Durban is far better positioned to respond to this future than many other South African cities, thanks in part to the iTrump program as well as other initiatives the city has taken to diversify its waste management. For instance, he points to an pilot program launched in Durban five years ago in conjunction with the paper firm Mondi, in which orange bags are delivered to households every week to be filled with paper and plastic. The initiative saves 117 tons of recyclable garbage from the landfills each month.

“Durban stands out as one of the few cities in South Africa that has multiple efforts to reduce waste,” says Dobson. “It has an efficient formal collection service, but it has supplemented that with recycling efforts like the orange bag initiative and through the waste-pickers. It has also started to engage around how to evolve these multi-sectoral initiatives appropriately. Durban is coming to grips with these challenges.”

As for Dube, he could care less about these perks, though they benefit him as they do every Durban resident.

“I would rather work in somebody’s garden or doing odd jobs,” says Dube, who earns an average of seven cents per kilogram for the waste he sells at the buy-back centers. “But I can always make money from this. There is always enough cardboard to collect and enough people to buy it.”

Photos by Greg Arde

_1200_700_s_c1_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)