To be a cyclist in America is to be hated by mostly everyone else. I’ve been a committed urban cyclist ever since I first moved to a big city when I was 20 years old. On one of my first commutes across the city of Washington, D.C., I remember braving the center of Connecticut Avenue as I prepared to turn left, and getting so flustered that a cop pulled up to ask if I was okay riding there. I said I was, though then I really wasn’t. Now I can handle just about any street, but my attitude these days can only be described as “battle-hardened.” You shouldn’t have to be battle-hardened just to get across town. But that’s what it’s like to be a cyclist in this country.

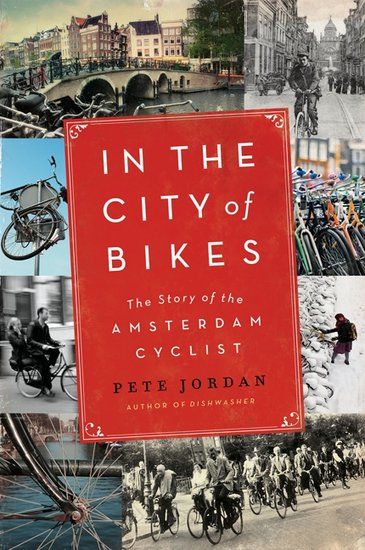

So I began reading Pete Jordan’s In the City of Bikes: The Story of the Amsterdam Cyclist with an optimism that the book promptly squelched. I had heard that, in Amsterdam, the culture of cycling is so strong that cars actually defer to cyclists. I had also seen this photo and wanted to read about a magical place where the rules and people were so different than they are here. It sounded too good to be true and, as Jordan tells it, that’s because it is.

In the City of Bikes reveals that it is indeed much, much better to be a cyclist in Amsterdam — but not because the powers-that-be have embraced the way cycling benefits the city, nor because the city is so well designed for it, nor because non-cyclists have a respect for people on bikes. The reason Amsterdam cyclists have it better is because so many people in Amsterdam ride bikes. Over the last decade or so, the city has finally begun to invest more in bike infrastructure and cyclist safety, but the war between drivers and cyclists raged in the Netherlands much as it has raged here. The key difference being that Amsterdam has so many more cyclists that they did, eventually, sort of start to win.

So are there any lessons we can learn from Amsterdam to encourage cycling in America? The answer I got from this book: not really. Not yet, anyway. Early on Jordan makes it clear that explicit, pro-bike policymaking is new to the city. For most of the history of cycling in Amsterdam, as he tells it, local authorities tried to rein cyclists in. Cyclists were banned from time to time on certain streets. There was even, for some time, a bike-specific speed limit (12 kilometers, or 7.5 miles, per hour), and failing to abide by it would result in a ticket — though cyclists still mostly ignored the rule.

Jordan has a series of explanations that, together, somewhat explain why folks in Amsterdam bike more than they do here. Most of it comes down to cost: The price of car ownership and operation is much more expensive. And then there’s the way that the Dutch value thrift. Jordan writes that there is less pressure in the Netherlands to look more prosperous than you really are, so no one will mock you for riding a bike even if you can afford an automobile.

I can’t say whether or not that’s really true for Dutch people, but I can say that the opposite is true for Americans. I’ve listened to groups of marginally and under-employed people make fun of others who use public transportation. It’s bafflingly myopic, but it’s the norm.

So here’s the recipe for getting more cyclists on the road in America: 1) Dramatically increase the price of gas, 2) redesign all of our urban areas after old European cities so there isn’t room for street parking, and 3) transform America’s relationship with money so that status symbols of material success no longer earn social approval.

Oh, and the U.S. could benefit from one more thing: Bike riding royalty. We kind of had that once but we seem to have lost it. Mostly.

In the City of Bikes tells the whole story of cycling in Amsterdam, from its early days — the days of the fietsjongens, or bike delivery boys — to the Nazi occupation, when almost all bikes were stolen for the war, to the end of the era of the zwijntjesjager (the bike thief, who operated with such impunity that nearly everyone in the city rode stolen bikes). It also tells Jordan’s personal story, from his decision to move to Amsterdam in grad school the opening of his wife’s bike shop and the birth of their always-on-a-bike baby.

You also learn that Jordan is a weird guy. First, he really likes to count things, and at one point even refers to counting bikes on the street as his “dream job.” Second, he reports spending a stunning amount of free time searching for a stolen bike that cost him maybe $100 (he doesn’t find it). He also spends several years working as a janitor just so he can keep living in Amsterdam and ride bikes with lots of other cyclists, even though he had already published one successful book by the start of the story and quickly earns his Master’s Degree in urban planning.

Strangely, I can relate to this last decision. To me, widespread cycling is the sign of a truly civilized place, one where folks choose to make (what appears to be) a sacrifice in individual comfort so that everyone can become more comfortable. In other words, if I opt to bike rather than drive, it may wear me out and make me sweaty, yielding less comfort than driving. But if everyone opts to bike, I experience less stress and more health so that I am, on balance, even more comfortable than I would have been in a car. They seem to have achieved that in Amsterdam. (And Copenhagen, too. I was disappointed when Jordan basically punted on the question of which is the better cyclist city, but maybe BikeSnob knows?)

Jordan shows us that irrational hatred of cyclists by drives isn’t unique to America. One lesson Amsterdam cyclists eventually learned, and that cyclists everywhere can emulate, is that they had to organize themselves. At first, bikes ruled — no need for organization. Then cars came along, and drivers formed advocacy organizations and with actual members. As Jordan tells it, it took decades for cyclists to seriously get organized (there were groups, but not many people joined), and once they did they were able to start pushing the city toward a pro-bike policy. America has had bike advocacy organizations for years, but they tend to take a pretty apologetic stance to cars, accept their place as second-class citizens and, most strikingly, advocate that cyclists abide by rules of the road that weren’t designed for them. Cyclists should not only organize but assert themselves as a different class of transport. As Randy Cohen wrote in the New York Times in August:

Laws work best when they are voluntarily heeded by people who regard them as reasonable. There aren’t enough cops to coerce everyone into obeying every law all the time. If cycling laws were a wise response to actual cycling rather than a clumsy misapplication of motor vehicle laws, I suspect that compliance, even by me, would rise.

If anything, In the City of Bikes is discouraging because it suggests that even in a place where cyclists are so prevalent, they still have to fight for their piece of the road (rather than everyone sharing the road and treating it like the commons it is). The book also makes it seem as though drivers share a universal entitlement that cyclists simply don’t have.

It’s also a portrait of a place where people really do live differently, even in the auto age. Where cyclists and drivers and pedestrians have grown accustomed enough to each other that so long as everyone keeps moving, it all works out pretty okay. If you’re a frustrated bike commuter, the book may give you some hope. If you’re like me, though, it may lead you to start looking into ways to move to the Netherlands. Because even if it isn’t a perfect place for bike riding, it sure sounds better.

Brady Dale is a writer and performer living in Brooklyn. You can find him on Twitter.

Brady Dale is a writer and comedian based in Brooklyn. His reporting on technology appears regularly on Fortune and Technical.ly Brooklyn.