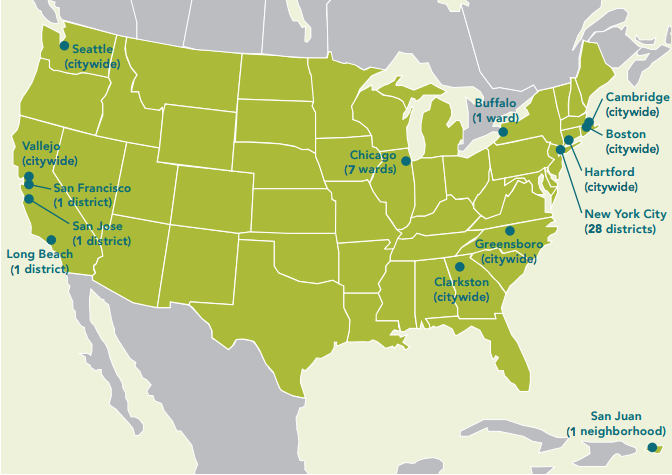

Participatory budgeting, a process that allows citizens a say in how public money is spent, is a fast-growing local governance trend in the U.S. Just one council district used the process in the 2009-2010 cycle. In 2015-2016, 47 cities or city council districts did.

But according to a new report by Public Agenda, whether this trend continues to grow and take root is largely dependent on whether elected officials are motivated to implement it, and stay dedicated once they do. The report, based on confidential interviews with 43 elected officials — 28 who’ve used participatory budgeting, and 15 who haven’t — lays out some of the challenges and successes.

Interestingly, most officials who had adopted participatory budgeting told Public Agenda they hadn’t necessarily done so to make the budget more responsive to community needs. Rather, they saw it as a way to educate their constituents about politics and get them more involved in local affairs. That motivation wasn’t devoid of self-interest, either: Most expected the process to build trust and gain them popularity within their communities.

And when it came to generating excitement and engagement, the process seemed to work. Officials reported that residents not usually involved in politics had participated, and many noted that bringing new players to the table seemed to foster relationships among previously disconnected community groups. Another Public Agenda report released earlier this year found that in most communities that had implemented participatory budgeting, lower-income and black residents took part in the process at rates at or above their neighborhood representation, according to census data. Women made up 63 percent of participatory budgeting voters.

Thus while elected officials said the process had led to frank and necessary conversations about equity, they also said the process could be frustrating for residents, who got to see firsthand just how inefficient government spending can be.

One official worried this could lead to voters becoming apathetic again. One quote: “The capital process is so dysfunctional. I’m worried that when people opt for projects and then see no immediate results, it is only going to add to their disenchantment.”

Others seemed irritated that people didn’t seem to understand the limits of what government can and cannot provide.

Still, through the process, even officials who said generating new ideas wasn’t their primary goal in implementing participatory budgeting reported that it had indeed made them more aware of their communities’ needs and beliefs.”

Before, one official said, they’d heard a limited set of ideas, primarily from organized groups of residents: “Now I am tapping into ideas that were not available to me before.” Another reported that the ideas generated through participatory budgeting, even if they don’t make it into the budget, could still be used “for legislation ideas, for policy changes, for community organizing opportunities.”

Officials also said that just as citizens connected in new ways through the process, government departments had to work together in new ways to make it happen. That led to some growing pains, as new partnerships formed, and points to one of the biggest roadblocks to implementing participatory budgeting: a lack of staff capacity. Time, money and staff were among the biggest challenges cited by officials. Reaching people who wouldn’t normally show up for political meetings required extra resources, and officials worried that only the well-off and well-represented would attend. Overall, officials felt more funding would need to be committed in order to do the process well.

Other frustrations included the difficulty of explaining the process to constituents and keeping participants interested even when they learned their ideas didn’t fit the type of projects participatory budgeting could fund. Including youth and utilizing technology for outreach both proved more difficult or controversial than expected.

Still, the report states that with few exceptions, officials who had engaged in participatory budgeting didn’t see these struggles as reasons not to keep trying. “I kept on hearing from other officials that every ounce of energy, and money, and whatever staff time was put into it, you get three- or fourfold back,” one official said.

For those officials who have chosen not to implement participatory budgeting, resources were a concern, but many also said they were attuned to constituent needs without it. “I was elected to represent my community. I speak with my civic leaders and to my constituents every single day through Twitter, Facebook, meetings, letters, calls. I have the pulse of my district. I’m here to take my community input, to use my experience, my knowledge of the inner processes of government and my judgment and make decisions that I think will have the best bang for taxpayer dollar,” one said. Another was more succinct: “I’m going to do the right thing, not the popular thing.”

The report concludes with recommendations for those who still want to try participatory budgeting. For officials and city staff, Public Agenda suggests partnering with community-based organizations and civic leaders to overcome the dearth of city resources and help spread the message to increase engagement. It also urges them to be prepared to see the best and worst of their constituents emerge. “Be ready for messy democracy,” it warns.

Jen Kinney is a freelance writer and documentary photographer. Her work has also appeared in Philadelphia Magazine, High Country News online, and the Anchorage Press. She is currently a student of radio production at the Salt Institute of Documentary Studies. See her work at jakinney.com.

Follow Jen .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)