Being a historical society in the 21st century means grappling with declining attendance, ebbing participation and dwindling sources of funding. It also means asking big questions about the value and purpose of public history.

Many local historical societies opened in the nineteenth century and existed to celebrate a specific history — namely, that of the white “pioneers” who first colonized that part of the world. They were founded by community boosters who are long dead, and the stories they tried to tell are not necessarily meaningful today. This leaves historical societies trying to figure out how to appeal to new audiences, many of whom are younger, as well as people of color who were often deliberately excluded from those histories.

Mahoning Valley Historical Society is an excellent example of this struggle. Founded in 1875, The Mahoning Valley Historical Society in Youngstown, Ohio, began as the sort of “pioneer heritage” institution that was common to many historical societies, but by asking tough questions and reshaping itself for the 21st century, it has not only survived, but it has expanded — even in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. By hosting community conversations on current events and painful parts of Youngstown’s history, the society has reinvented its mission as a civil institution.

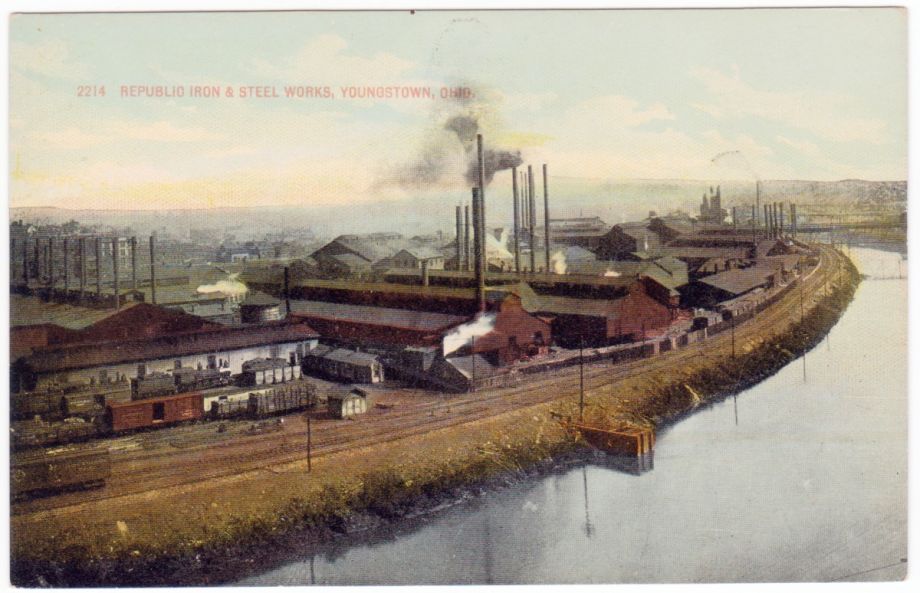

The success of the historical society is all the more striking given Youngstown’s association with industrial decline. The city has lost 60% of its population since 1959, and the steel industry that was once the city’s economic backbone is mostly gone. In recent years, it has taken a number of steps to attract new industries — tech in particular — but the process of rebuilding the city’s economic base, and therefore the historical society’s potential donors, is a slow one. Given the circumstances and the city’s history over the years, how has it managed to support a steadily growing historical society?

The historical society measures success not solely in “in the feedback we’re getting from the community, from people who attend our events,” according to Traci Manning, Curator of Education at the historical society. While tracking attendance and donations are important metrics, community response ultimately tells them how they’re doing. This means being willing to discuss uncomfortable topics, neglected histories, and occasionally contemporary issues.

Some of their successes have simply been down to good management and good luck. The society moved into new facilities in 2009, buying a vacant building and adapting it into the Tyler History Center. Moving that year allowed them to buy the building cheaply. Manning attributes the society’s fundraising success to good community relationships. A substantial portion of the center’s fundraising comes from smaller community donations from creative campaigns. A common fundraising campaign involves asking donors to sponsor an engraved brick; the Mahoning Valley Historical Society offered engraved Good Humor Ice Cream Bars — the company was founded in Youngstown — for people to put in their homes.

Some of those donations come from events that blend fundraising, programming, and community engagement. One example of that is the society’s cookie table fundraiser. Youngstown and Pittsburgh are home to this unique wedding tradition which was introduced by European immigrants early in the twentieth century. (Both cities lay claim to creating this tradition). John Slanina, a resident and volunteer at the historical society, says that Youngstown itself is a cookie table “…you have Greek baklava, Italian wedding cookies, Slovak kolache.” Beginning in 2011, the historical society began hosting “cookie table fundraisers” that drew people in, raising tens of thousands of dollars at a time.

Other community events have proved to be effective at reliably drawing younger people into the historical society. Slanina’s favorite event is actually a scavenger hunt, in which participants drive through the city looking for Youngstown’s historical ephemera. It’s called the Great Youngstown Race. “That was my entryway to becoming a volunteer with this organization,” Slanina recalled. Other events include cocktail nights, often held in collaboration with Youngstown’s various ethnic societies like the Polish-American Club.

This kind of programming builds community engagement, but the society is also committed to education. Manning spends weeks at a time working in schools in and around Youngstown, putting together programming for students. “We work for every school in two and a half counties,” Manning says. “We keep the groups really small so we can be interactive with the students and it’s always hands-on, whether that’s an artifact program for elementary-school students or a primary-source program for high school students.”

When the society presents at schools, “We don’t gloss over anything, we don’t whitewash anything, and I think a lot of the schools around here really appreciate that because a lot of times it’s stuff they’re not studying,” Manning says. Speakers’ series include histories of propaganda for eighth-graders, focusing on how the civil rights movement was represented by its opponents, or local histories of immigrants who came to Youngstown. They offer many of these curricula as teaching kits.

When asked how Mahoning Valley handles its recent and sometimes difficult history, including its decline, Manning laughs. “I don’t feel like that’s a difficult history at all.” In September of 2017, the historical society held a panel discussion on “Black Monday,” the day in 1977 that Youngstown Sheet and Tube abruptly closed, throwing five thousand people out of work in one stroke. The forum was packed full of people offering up their memories of that day, what it had meant to them, and what it had done to the community.

The society also helps to bear witness to events in the community today. On August 16, 2019, the city’s newspaper, the Youngstown Vindicator, announced that it would be closing its doors at the end of August. The society held a community forum for people to discuss the issue. Some people wanted to try and find ways to save the newspaper before it closed. For others, it became a place to remember the Vindicator and what it had meant to them, as well as the next steps to try and develop a new community newspaper.

Partnerships are another way to tackle those hard conversations. In addition to hosting programming on African American history in Youngstown, the society partners with other organizations such as Mahoning Valley Sojourn to the Past. Run by Penny Wells, Sojourn to the Past takes students from the areas on week-long tours to famous areas from the Civil Rights Movement. The historical society supports these tours by cooperating with Wells and Sojourn to the Past on programming. According to Wells, working with the historical society was a natural fit “not because it was a historical society, but because of the people,” Traci and Bill Lawson, the executive director, in particular. That willingness to collaborate has won respect in the broader community, including from people such as Wells.

Wells alluded to the importance of the society as a venue. “Before the Tyler [center] opened [and] there wasn’t a place to have meetings or speakers, the African American community didn’t relate to the historical society.” That’s changed with the combination of programming and space offered by society. In February of last year, the society and Sojourn teamed up to show the documentary After Selma, bringing Joanne Bland, co-founder and former director of the National Voting Rights Museum in Selma, to speak. They also collaborated to host a discussion with Simeon Wright, Emmett Till’s cousin, and Dale Killinger, an FBI agent who resumed the investigation in 2004. Wells says these types of events have drawn in African American audiences, noting that the room for the showing of After Selma was “packed.”

The society’s strategies are not unique. A much smaller historical society, Highland County in Ohio, developed an exhibit and documentary on the integration of its school district following Brown v. Board of Education; it was the first community outside the South to integrate this way. New York City’s historical society began collecting artifacts from the George Floyd protests almost as soon as they had ended to foster conversations about police violence.

But by adopting these strategies, historical societies in turn re-establish themselves as anchors of the community. For younger people, this means more entertainment and fun programming that can still be anchored in history, but can also draw people seeking more community connections. This also means participating in debates around painful history. “We have so much success when we partner with other organizations,” Manning says. “The more voices we can get, the broader the story is going to be and the more complete the story is going to be.”

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)