In the annals of urban highway eyesores, the Elevado Presidente Costa e Silva that slices through the heart of Brazil’s biggest city is a strong contender for worst of the bunch. Better known as the Minhocão (Big Worm), the elevated hulk runs for 3.1 kilometers through dense neighborhoods, casting a forlorn shadow over the streetscape below. For decades, public opinion has demanded its demolition as part of a global trend in highway teardowns. But in a city starved for public space, a group of paulistanos hope that they can save the big worm from the wrecking ball thanks to another global trend: elevated parks.

Mayor Paulo Maluf — an infamous character wanted by Interpol on conspiracy charges — oversaw construction of the Minhocão in 1971, at the height of Brazil’s military dictatorship, and named it in honor of the general-cum-president who had appointed him to office. “Coincidentally, the Minhocão ends right in front of Maluf’s company headquarters,” says Athos Comolatti, president of the Friends of Parque Minhocão, an advocacy group that hopes to preserve the highway as a permanent park. “Everyone says he built it to get from his house to his office without traffic lights.”

That origin may be apocryphal, but the Minhocão is an undeniable anomaly, running a short length without connecting to other highways. After a decade of complaints over traffic noise and frequent nighttime accidents, in the early 1980s the Minhocão began opening only from 6:30 am to 9:30 pm, Monday to Saturday. How paulistanos use the highway on its day off, meanwhile, has made the Minhocão one of the most vibrant places to be on a Sunday in the concrete jungle of São Paulo.

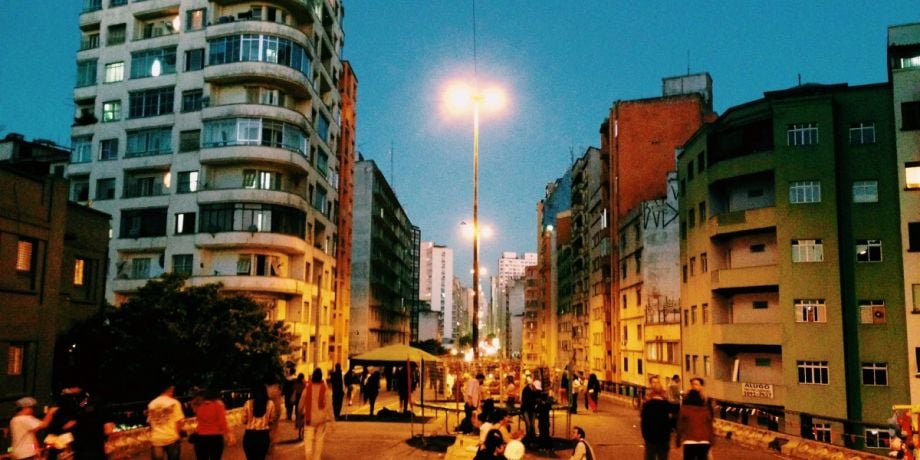

The Minhocão at twilight. (Rodrigo Vieira on Flickr)

“All it takes is removing the cars for people to use the space for exercise and cultural events, all organized by everyday citizens,” says Jeniffer Heeman, president of the Brazilian Placemaking Leadership Council. Unlike other elevated parks like the High Line in New York, the Minhocão is laissez-faire territory accessible by gates that block cars, but easily bypassed by pedestrians. It’s a DIY park — open to all and infused with the thrill that comes with frolicking on a suddenly still highway.

“Officially, city hall doesn’t recognize it as a public space,” says Comolatti. “They tolerate it, but you won’t find it on any maps.”

While plenty of people lace up their shoes for a short jog or help their kids master training wheels, the wide roadway accommodates plenty of other uses. Sidewalk chalk art takes on a bigger scale, like the enormous flower designed by artist Felipe Morozini’s Hanging Gardens of Babylon in 2009, one of the first artistic installations to envision the highway as a park. Rolling out sod for a makeshift parklet, à la (Park)ing Day, along with some cheap plastic furniture and a portable sound system equals instant dance party. Inevitably someone hauls up a charcoal grill for churrasco (barbecue), a Brazilian Sunday tradition.

A collaborative of activists, artists and residents called Baixo Centro (rough translation: Lower Downtown) has organized some of the more involved events with the explicit mission of appropriating the public space for interaction across class and cultural lines. They call it a “civil occupation.”

Baixo Centro’s motto is “streets are for dancing.” This photo was taken at a festival the collaborative held on the Minhocão in 2012. (Photo by Lets on Flickr)

“We thought the structure could become a stage with the tagline ‘streets are for dancing’ that would bring together both Upper and Lower Downtown [the two ends of the Minhocão, one more and one less affluent] for a discussion about public space,” says Thiago Carrapatoso, who made it clear he speaks individually and not on behalf of the decentralized movement.

These efforts imagine another life for the decrepit highway also another way of interacting in São Paulo, the largest city in South America and one with a long history of extreme disparity between the rich and the poor

“It’s hacking the streets, like in our mission statement,” says Carrapatosa.

A cyclist rides down an empty Minhocão. (Photo by Bruno Fernandes on Flickr)

The Minhocão has become a diamond in the rough, an unpolished and unexpected contribution to a city that, like many in the U.S, has failed to deliver the same level of parks to rich and poor areas.

Gritty and unmanicured, it stands in stark contrast to the immaculately landscaped Parque Iberapuera, São Paulo’s answer to Central Park, located in a rich area with no subway access.

But even as the crowds who flock to the park each Sunday prove the demand for the concrete park, the city’s political leaders remain unconvinced.

“All the mayoral candidates get asked what they will do to it,” says Comolatti, “But no one will touch it.” The first park proposal emerged in 1987 and was deemed ludicrous. When New York’s elevated gem opened, the Friends of group dug up the old plans.

“Once the High Line was built, I realized they can’t knock down the Minhocão. But to my surprise, everyone kept talking about demolition,” Comolatti says. The previous mayor even put out an RFP, but a technical error in the bid documents slowed the process until he left office. The current mayor, Fernando Haddad, has been more equivocal, saying publicly that it never should have been built, a less enthusiastic response than Friends of Parque Minhocão had hoped, especially after they hosted a critically acclaimed exhibit on the High Line in their office – an apartment overlooking the highway – during the 10th São Paulo Architecture Biennial in 2013.

The Minhocão becomes a space for relaxation above the crowded city on Sundays.(Photo by Lets on Flickr)

“City hall is out on a limb on this one,” Comolatti says. “For forty years everyone has been talking about knocking it down. This idea of making it a park has only been in the wider public conversation for a year. They can’t just turn around on a dime and say it will become a park.”

While politicians dither, the city continues to grow around the elevated highway, which skirts many of downtown São Paulo’s major attractions, from the bohemian nightlife of Rua Augusta to the stately symphony hall and runs along the edge of the gentrifying Luz District. In many ways, the highway’s blighting effect has been a boon for low-income families looking to gain a toehold in the mega-city, where commutes can stretch to hours for residents on the urban periphery, home to most affordable housing.

“The Minhocão cuts through neighborhoods that were or still are relatively nice,” says Patricia Samora, a professor of architecture and urbanism at the Universidade São Judas Tadeu. “But when it was built, higher income people left and since then it’s served as a rental alternative for poorer families.”

For these families, Samora says, the idea of turning the highway into a park is complicated by fears that the new amenity would drive up real estate values and eventually, make it unaffordable for them.

“The mere mention of revitalizing the Minhocão, whether demolishing it or turning it into a park, is already being used by real estate developers as a sales pitch,” she says. “With the expectation of something happening soon, families are already reporting difficulty in renewing their leases.”

While the debate rages over a potentially transformative public space in São Paulo, the lessons from the Minhocão’s initial top-down construction are clear: Without careful and inclusive planning, even as a park, the big worm could prove a leviathan.

The column, In Public, is made possible with the support of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

Gregory Scruggs is a Seattle-based independent journalist who writes about solutions for cities. He has covered major international forums on urbanization, climate change, and sustainable development where he has interviewed dozens of mayors and high-ranking officials in order to tell powerful stories about humanity’s urban future. He has reported at street level from more than two dozen countries on solutions to hot-button issues facing cities, from housing to transportation to civic engagement to social equity. In 2017, he won a United Nations Correspondents Association award for his coverage of global urbanization and the UN’s Habitat III summit on the future of cities. He is a member of the American Institute of Certified Planners.

_920_690_80.jpg)