Charleshon Goodman was born and raised in a housing project out in Hunters Point, the historically African-American enclave along San Francisco’s southeastern edge. The neighborhood is well known for its legacy of heavy industrial pollution, but Goodman’s one of a new generation of local youth who’s getting green education and a paycheck from environmental jobs.

The 21-year-old went through a training program called Roots of Success, offered by Hunters Point Family, a community organization, when he was 16. The program includes 10 weeks of learning about wind farming, solar farming, sustainable agriculture and other green practices, and promotes more than 125 different green careers in the process. At the end, students get a certificate honored by employers throughout the Bay Area. They’re also paid to attend.

Now, Goodman helps Hunters Point Family run a community garden in his neighborhood. He says the work is changing lives.

“It’s definitely helping the youth open up and make those day-to-day changes,” he says, citing healthier eating habits and an awareness of how they can reduce pollution. “Working with them you get to understand some of the challenges they face in their housing, and how the outside environment can extend into the home.”

Hunters Point is home to one of California’s Superfund sites, an Environmental Protection Agency designation that flags “the nation’s most contaminated land.” The local U.S. Navy port pumped tons of contaminated water into the San Francisco Bay and onto port grounds, tainting water and soil with discarded “paints, solvents, fuels, acids, bases, metals, PCBs, and asbestos,” according to the EPA.

When the port first opened up in the 1930s, African-American workers from throughout the U.S. moved in to construct ships. Its closure in the 1970s pulled the rug out from beneath the neighborhood’s economy, which the city is now trying to remedy with private development and workforce training. Fears of displacement, however, are on the rise.

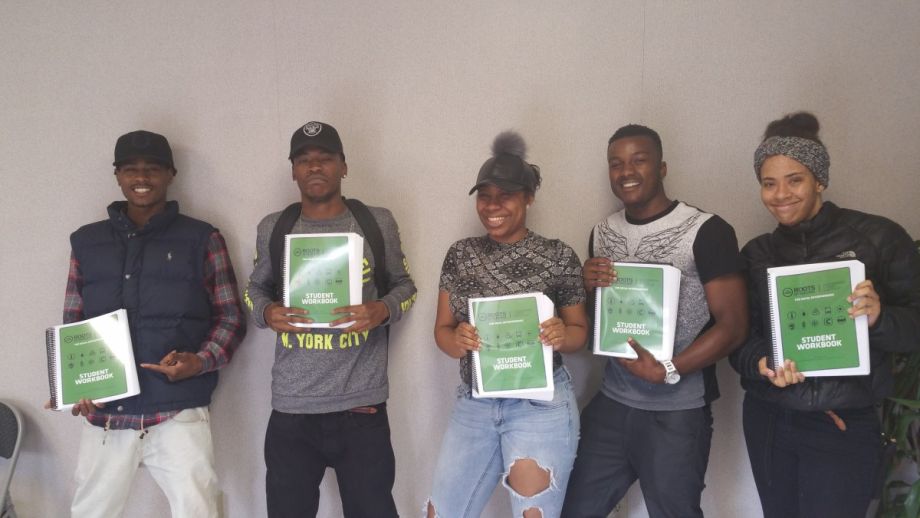

Roots of Success trainees in San Francisco

She started working with local advocacy group Literacy for Environmental Justice when she was 18 years old, joining park cleanup efforts and helping out in a local garden right across the street from public housing in Hunters Point.

“They provided jobs for the youth in the community, but also provided little spaces for the community to come in and plant their vegetables,” remembers Vargas, who has since worked for the San Francisco Recreation and Parks Department. “It’s awesome that they got that opportunity and it was so close to their home.”

The neighborhood has around 36,000 people, the majority of which are African-American. About 83 percent of the entire population identifies as belonging to a minority group.

But even though San Francisco is riding a job boom, with unemployment rates dropping to 2.7 percent in July 2017, nearly one-fifth of Hunters Point residents are struggling to find work. Throughout the city, black unemployment rates are critically high, ranking between 17 and 64 percent even though black communities only make up 4 percent of the population citywide.

“It’s unacceptable,” said Board of Supervisors President London Breed, during a hearing on San Francisco’s workforce programs in March. Eighty-nine percent of the San Francisco Office of Economic Development’s workforce training support ends up going to workers of color from areas like Hunters Point. A recent report from the Brookings Institution, however, showcased that San Francisco has the greatest employment gap between black and white communities in the country outside Detroit.

“We flaunt this economic prosperity, its booming healthcare sector, technology, hospitality, construction — all of this incredible prosperity in San Francisco [yet] clearly what we’re doing is not working” for African-Americans, Breed said.

Meanwhile, the city’s high cost of living is pushing inner residents out to cheaper real estate markets like Hunters Point, where a private construction company is building 12,000 new homes, and restaurant sales tax in the region spiked 135 percent between 2015 and 2016. The white population percentage jumped from 10 percent to 17 percent in the neighborhood between 2000 and 2015; African-American populations dwindled from nearly half to one-third in the same time period.

But programs like Greenagers, Friends of the Urban Forest, the YMCA’s Environmental Advocates Program, and others have found a niche by giving Hunters Point youth job experience that battles local environmental and health ills. High school locals are signing up for summer opportunities that start out at $13 an hour, the city’s minimum wage, and pair them with leaders and peers from their slice of San Francisco.

“Kids are really, really interested in working in the garden, but it’s that economic incentive that comes with it,” says Kenneth Hill, a program director for Hunters Point Family. “They’re getting the experience, but they’re also getting paid.”

Hill started with the organization after working with programs like the Southeast Food Access Working Group Food Guardians, which promotes nutritious food choices to Bayview-Hunters Point residents. He’d host stands at local grocery stores in the neighborhood, demonstrating to customers the types of recipes you’d find at a Whole Foods. Recently he ran into an old neighbor who told him she still makes the black bean mango salsa he mixed up one afternoon.

The next step, he says, is to get neighbors like her to use the produce his kids are cultivating. Hill says they’ve brought in 60 kids, ranging from ages 9 to 19, to work their local gardens this year. In them, Charleshon Goodman sees the seedlings of a new Hunters Point generation.

“They’re all relatable,” he says. “I see a little bit of myself in each and every one of them.”

Johnny Magdaleno is a journalist, writer and photographer. His writing and photographs have been published by The Guardian, Al Jazeera, NPR, Newsweek, VICE News, the Huffington Post, the Christian Science Monitor and others. He was the 2016-2017 equitable cities fellow at Next City.