The Black Youth Project, a Chicago-based research center, released a wide-ranging report on black millennials earlier this month. The fruit of surveys taken across a decade, the report doesn’t solely share perspectives on black millennials, but also how their responses differed from their white and Latino counterparts.

Many outlets have called attention to the study’s findings on policing. Indeed, police violence is too familiar for black millennials: More than half said they knew someone who had been harassed or brutalized, or had been victims themselves.

There are many more telling results across the study’s 88 pages that have been much less explored. More than half of black and Latino respondents, ages 18 to 29, said their salaries didn’t allow them to cover their finances; more than a third of white respondents in that age group answered the same. One in five black millennials said that they had faced discrimination while looking for work; between three and four white young people out of 100 had. More than a third of black women said they had experienced some form of discrimination in the workplace.

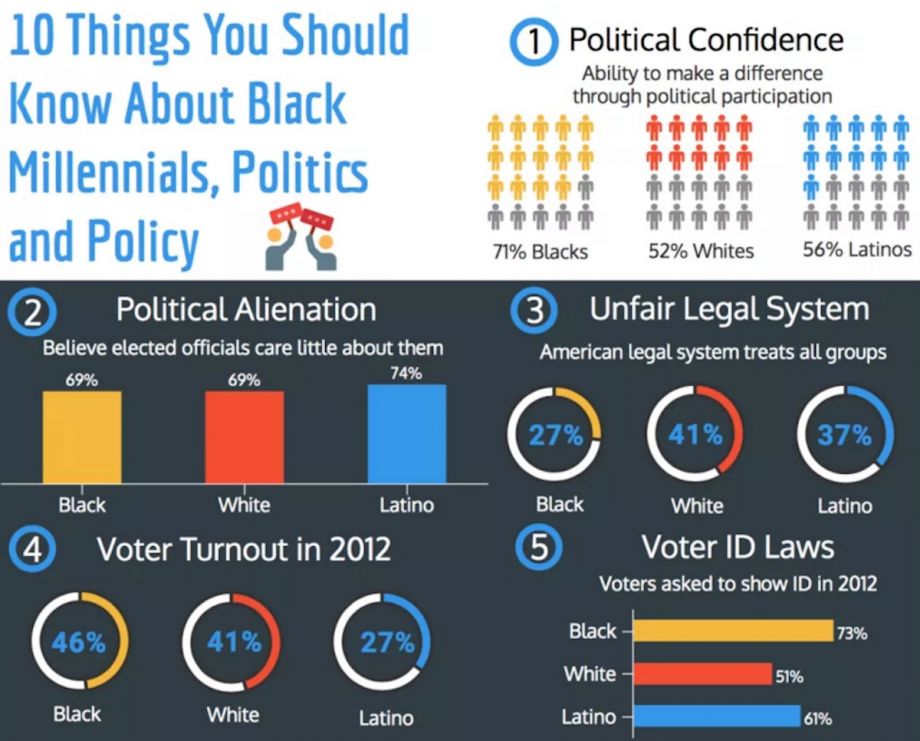

(From Black Millennials in America)

While around half of white millennials said they didn’t fear gun violence, only three in 10 black and Latino millennials surveyed could say the same. Millennials across demographics were in favor of gay marriage, allowing same-sex couples to adopt and equal employment rights for LGBT Americans at comparable rates, but blacks were more likely to name HIV prevention, not marriage, as the most pressing LGBT issue of the day. Blacks and Latinos were more in favor of requiring police to undergo transgender sensitivity training. Two-thirds of black college graduates have at least $20,000 in student loan debt; under half of white and Latino grads do.

To many readers, none of this may come as a surprise. African-Americans have long expressed that disparities in policing, hiring practices and treatment in the workplace exist. If you are a black millennial, you can likely name loved ones who’ve been roughed up by police, who carry heightened financial pressures, or whose views on LGBT rights don’t quite reflect the media’s portrayal of how a black person would see such matters.

Jon Rogowski, one of the study’s authors and a professor at Washington University in St. Louis, is aware that the information they’ve packaged on higher rates of incarceration, poverty and unemployment is not breaking news.

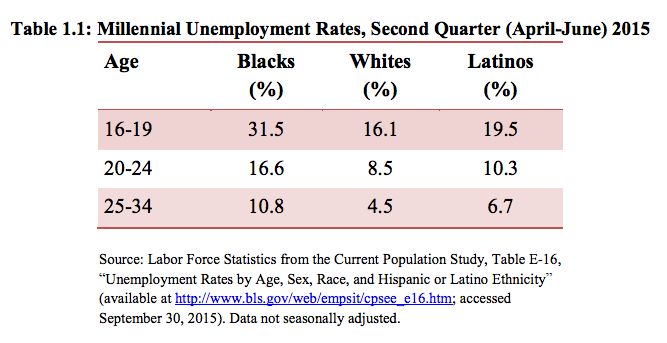

(From Black Millennials in America)

“We know these things are generally discussed, or sometimes talked about. But just looking at the numbers, seeing the numbers and statistics in front of you, really emphasizes the point that this is a group of young people who are experiencing in many cases vastly worse economic, health and criminal justice outcomes than their peers,” he says.

As Samuel Sinyangwe, Black Lives Matter activist and Mapping Police Violence co-founder, wrote for Next City, data is exposing truths in need of policy fixes, and young blacks are “using digital tools to sear a litany of injustices into the public consciousness.” The distance between what black youth routinely experience, and what whites know of it, is getting shaved in this process, and the links between data gathering and social change are tightening.

With the 2016 presidential election dominating the news, the report’s finding on political action is perhaps the most interesting story rendered. The majority of black millennials said that government cared little for them, but this group was most likely to believe they could make a difference in politics. Seven in 10 black millennials felt they could bring about change, according to survey results in 2014 (roughly half of whites and Latinos responded this way), a 30 percent leap over how black respondents answered just five years prior.

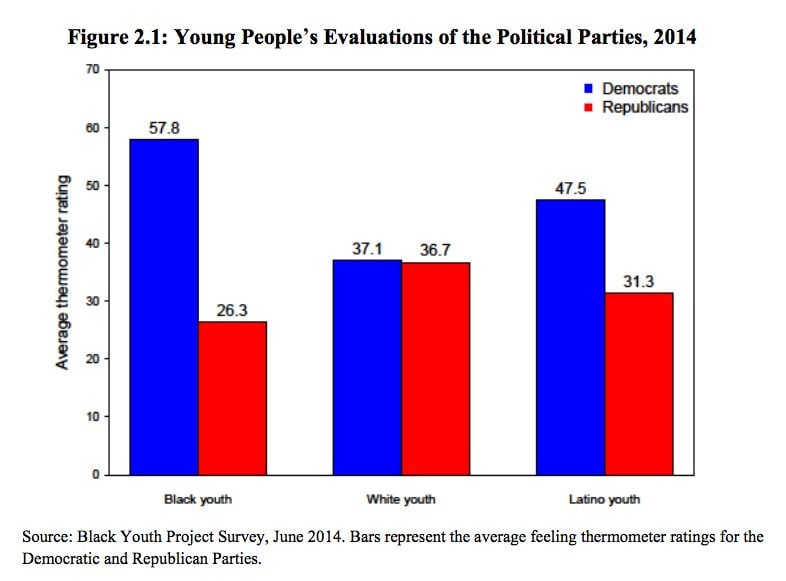

(From Black Millennials in America)

“The typical story is that wealthier people with more resources are more likely to participate, to feel like they’re included in the political system,” says Rogowski. “But here when it comes to young people, we’re seeing that it’s the groups that tend be at the other end, that are experiencing the worst economic outcomes that are the most localized and motivated to participate.”

Another thing Next City readers know: Millennials, and their politics, are changing cities. And yet, often when the media tells stories about millennials, it comes across as a coded term, one that’s really referring to a subset of this generation that’s white, educated and urban. This skew doesn’t reveal the full scope of millennial attributes. Did the Black Youth Project have this mind while preparing this study?

“Let me just say,” Cathy Cohen, Black Youth Project founder and co-author of the report, replies in an email, “that part of our reason for focusing on Black Millennials was to recalibrate the national discussion about young adults. There is no coherent group of Millennials. We do young people a disservice when we act like there is political agreement among this group. We need to disaggregate the data and pay attention to where young adults differ based on race, ethnicity, gender and class as a start. Only then can we say we take serious the political voices of young people in all their complexity.”

The study does not include perspectives on how black millennials feel about cities, but the Black Youth Project is hoping to launch a monthly survey in the coming months where they’d ask about topics like that one. Rogowski says that other researchers, like those at Pew, have released reports on millennials in cities, “but they don’t break it down by racial group,” and that, “my hunch is that they simply do not have large enough samples of people of color to do so.”

Data like this, to put it mildly, would be nice to see.

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Cassie Owens is a regular contributor to Next City. Her writing has also appeared at CNN.com, Philadelphia City Paper and other publications.

Follow Cassie .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)