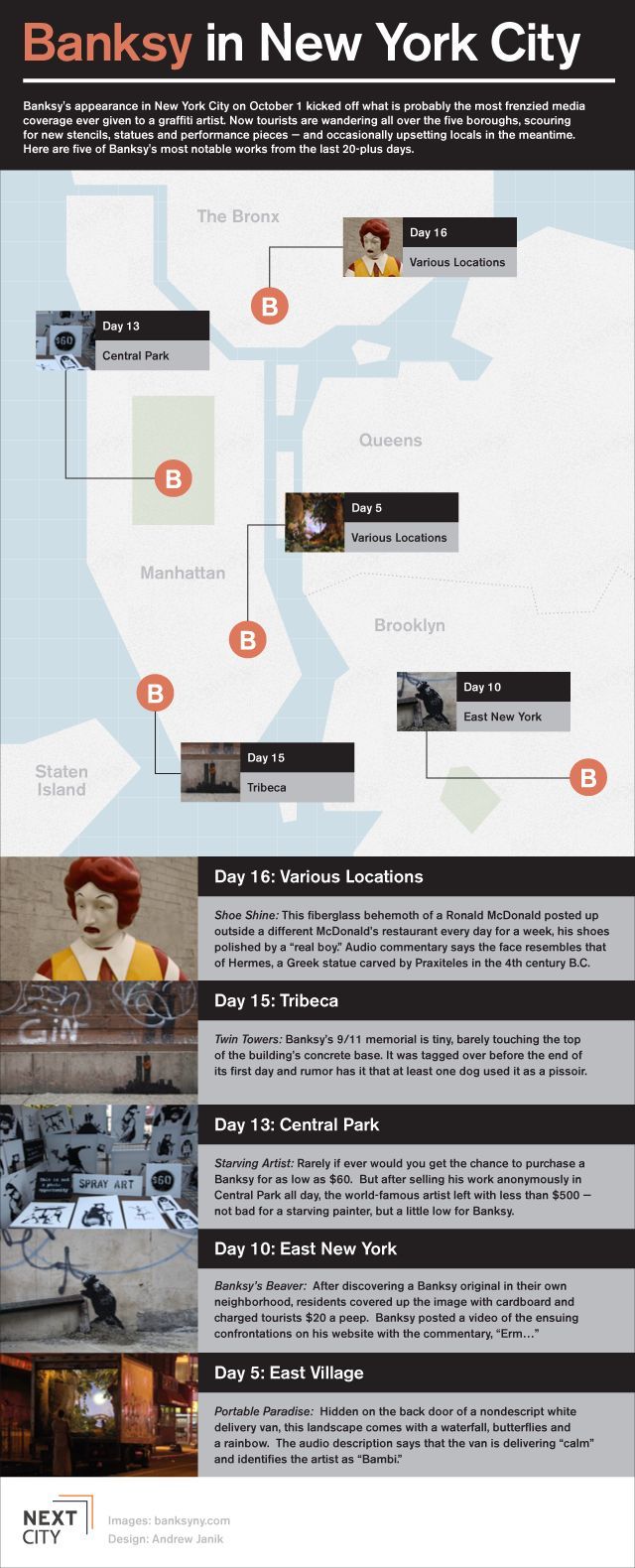

U.K.-based street artist Banksy’s arrival in New York City has already earned a lot of press, but not for the all reasons you’d expect. Called Better Out Than In, after a Cezanne quote about the importance of working outside the studio, Bansky’s New York residency features daily pieces that culture reporters and tourists alike have spent the better part of a month hunting for.

These include some of his signature ironic stencils as well as less typical works, such as a delivery truck filled with screaming stuffed animals, called Sirens of the Lambs, that drives around the Meatpacking District. Banksy chronicles all of the pieces on his website and Instagram, creating a mad treasure hunt by giving only vague clues as to each work’s location.

Banksy’s newest installations come with an audio tour on his website. Take his October 16 piece: A fiberglass Ronald McDonald, with giant clown shoes and accompanied by a live shoeshine boy, that welcomes visitors into a different McDonald’s location every day for a week. “The result is a critique of the heavy labour required to sustain the polished image of a mega-corporations,” the narrator deadpans, mocking trite questions visitors may have about the work. “Is Ronald’s statuesque pose indicative of how corporations have become the historical figures of our day? Does this figure have feet of clay and a giant footprint?”

World-famous and coveted by celebrities, Banksy never fails to attract a crowd. But given that the residency takes place outside museums or galleries, viewers were surprised when asked to pay to see one of his latest works. An October 10 stencil features an adorable beaver who has apparently chewed down a No Parking sign. The piece is located in East New York, and entrepreneurial locals were among the first to find it. They promptly covered the image with a piece of cardboard and began charging admission.

Cord Jefferson of Gawker praised the men, writing that the proprietors of the faux museum, “[H]eroes that they are, have elevated the original work, turning it into a performance piece about the commodification and hipster-fication of people’s homes.” Indeed, many Banksy fans have little reason to visit the high-crime area otherwise, but some were still outraged at the assumed scam.

Banksy’s high profile has made his “real” identity a subject of much speculation and prompted numerous attempts, and just as many false alarms, to unmask him. These attempts have only intensified this month: Someone affixed a tracking device to the Sirens of the Lambs delivery truck, which the artist then found and reattached to a car service vehicle from Queens. Banksy’s distinctive style and artistic themes have also made him an easy target for forgeries, some better than others.

In addition to forgers and amateur detectives, this month’s residency has brought saboteurs to the scene. From the beginning of the month, Banksy’s works have been tagged or written over completely, some within hours of their completion. He seems to expect this — often, the audio recordings keep pace with a work’s destruction, still maintaining their jaded tone and faux-tour guide lingo.

Banksy’s works have been defaced, erased or even chiseled from buildings before, but the speed at which the New York residency pieces have been disappearing has prompted some to take action. One piece in Red Hook, a floating red balloon with bandages, had already been tagged by the time the owner covered it with plexiglass (which itself has also been tagged).

Others have gone even further. Owners of the Williamsburg apartment building where Banksy painted two geishas crossing a bridge have spent thousands on the work’s protection, hiring $200-an-hour security guards and installing a $2,000 metal gate. Bystanders tackled a disguised vandal who tried to paint over the geisha piece and then scrubbed the piece clean by hand.

On October 18, the city awoke to another faux museum, this one created by the artist. Beneath the High Line on West 24th Street, Banksy created a temporary art gallery for spectators who prefer galleries with “more gravel in them.” Accompanied by a bench, and plenty of gravel, are two canvases. One is dark, grey and filled with armored soldiers and a lone, headscarved person. The second is warm and colorful, featuring many masked and scarfed figures and one grim, armoured soldier. This piece, too, has a security guard.

These recent controlled viewings once again raise questions about the commodification of Banksy’s work. Even away from the snooty galleries the artist likes to scorn, residents fixate on his works. Why? Because they are bonafide Banksy pieces. New York isn’t interested in graffart, it is interested in Banksy.

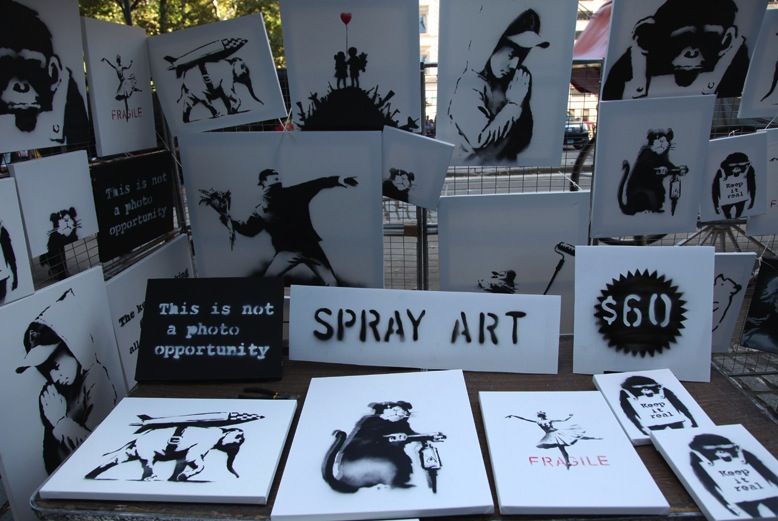

The artist is aware of this, too. On October 13, while Banksy maniacs prowled the streets looking for his newest work, he set up a stall in Central Park and sold small, limited editions of his work for $60 a pop, and left at the end of the day with less than $500. Authentic Banksy pieces have gone for six or seven figures, but only when customers can buy the name along with the work.

The conflict-filled nature of Banksy’s residency has kept people coming back for more, and other groups have taken advantage of the press. Mayor Bloomberg took the opportunity to speak out against graffiti. On a much more serious note, a man gave a speech in front of one stencil, chiding New Yorkers for spending more time looking for Banksy pieces than for Avonte Oquendo, an autistic 14-year-old who has been missing since October 4.

“I know street art can feel increasingly like the marketing wing of an art career, so I wanted to make some art without the price tag attached,” Banksy told the Village Voice earlier this month. “There’s no gallery show or book or film. It’s pointless. Which hopefully means something.”

That isn’t exactly the way things have played out. Banksy is the talk of the town like never before. Even if he started out using New York City as a blank canvas, it has still turned into one big gallery. Ironic, right?

A fun addendum: The Twitter account Banksy Ideas, which has more than 25,000 followers, has been posting ironic ideas for Banksy art for months. Some of the Tweets are hilarious:

Stencil of Nigel Farage wrestling a man-sized croissant. The croissant has him in a headlock, yeah?

— Banksy Ideas (@BanksyIdeas) May 5, 2013

Some are obvious:

Stencil of a robotic Uncle Sam on a poster. The caption reads ‘I want YOUR private data.’ Prism, yeah?

— Banksy Ideas (@BanksyIdeas) June 11, 2013

Almost all, however, are feasible Banksy pieces. Aside from mockery and publicity, what is Banksy bringing to the art world these days? Maybe this entire residency can be summed up by Banksy Ideas’ favorite sign off: “Well ironic, yeah?”

Stencil of Kate Middleton holding her baby. It’s got Will Smith’s grinning face & wearing a back-to-front baseball cap. Fresh Prince, yeah?

— Banksy Ideas (@BanksyIdeas) August 6, 2013