Just about every workday for the past month, Stephanie M. Smith has walked into Baltimore Police Department Headquarters, at eight in the morning, prepared to talk about the city’s legacy of segregation and systemic underinvestment in communities of color. She goes to represent the city’s Department of Planning at a daily interdepartmental meeting, convened by Mayor Catherine Pugh, to coordinate efforts to respond to Baltimore’s wave of violent crime.

Smith is the planning department’s assistant director for equity, engagement, and communications. She is the first person ever to hold that position, created in July after a two-year internal soul-searching process at the planning department that pioneered the use of zoning as a tool for racial segregation in 1910, when the New York Times reported that Baltimore was the first city in the United States to pass an ordinance mandating separate neighborhoods for white and black households.

“We’re here in the 21st-century operating off of a game plan that in many ways was conceived in the late 19th, early 20th-century,” says Smith, an attorney by training who has worked in environmental justice. “That system outlived its creators, but we have an opportunity within planning to un-plan some of the inequities in ways that will outlive us.”

While Baltimore’s violence and loss of life have been tragic, the daily meetings at the police department are helping to connect the dots: The places where there is the most violence are the same that the city has historically neglected with its own public dollars. Those conversations about the short-term are tee-ing up Smith for longer-term conversations coming up this fall. In Baltimore, the Department of Planning manages the city’s capital budget process, in which it helps other agencies decide where to spend their capital budgets — funding for infrastructure, public spaces, recreation centers, building or improving all kinds of city-owned “brick and mortar” projects.

“[The daily meetings are] teaching people to think holistically about communities in a way that I think will be helpful as the capital budget conversations get going, so that later on I can lift up that their agencies are concerned about these communities experiencing high levels of violence, and from there how can we think about how this capital budget process can also alleviate some of those issues,” Smith says.

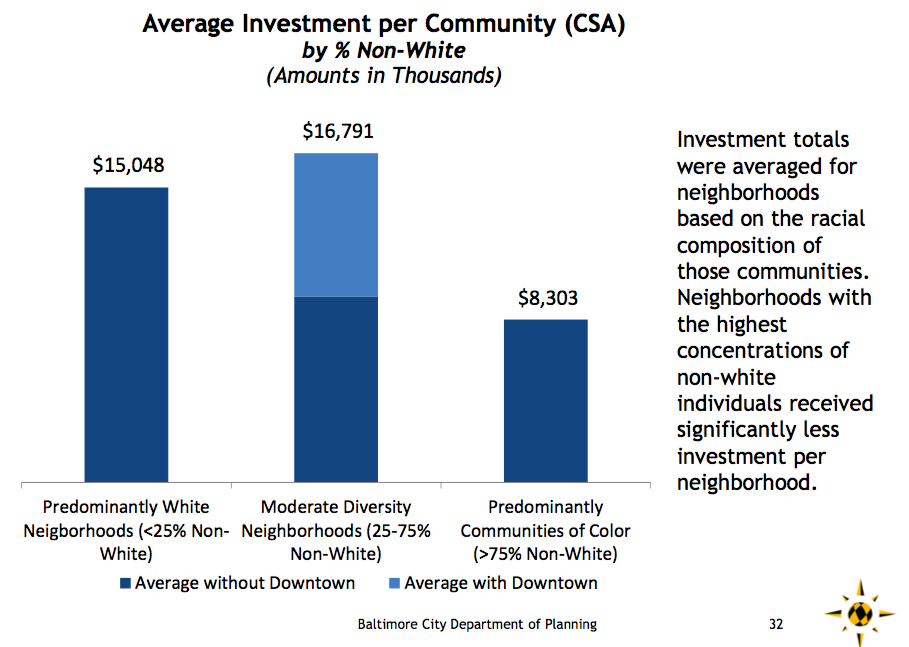

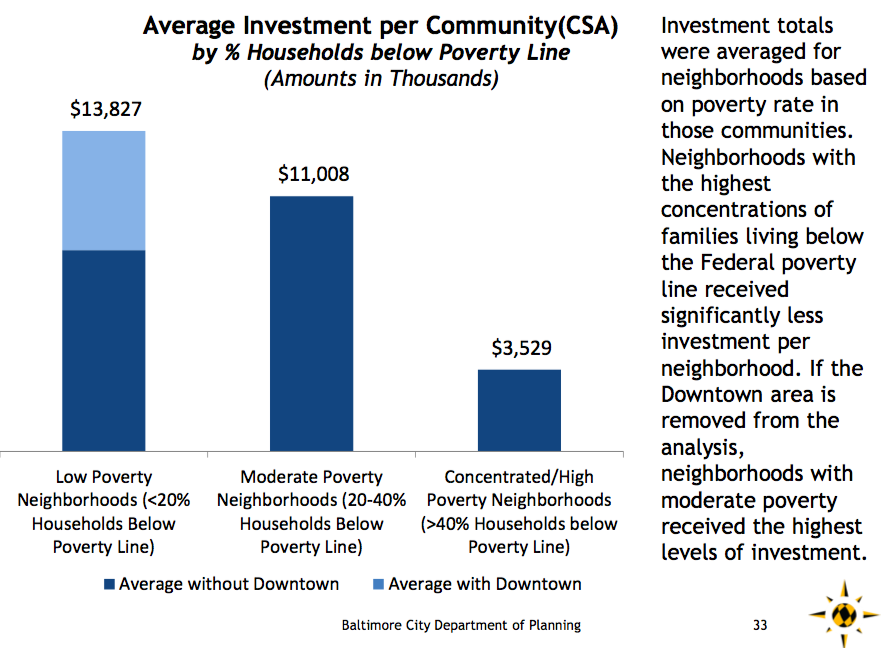

Thanks to the research done by the planning department, Smith can walk into those discussions armed with data that shows the city itself has been “redlining” — intentionally or unintentionally avoiding investments into areas that are predominantly people of color or low-income.

Data from a preliminary equity analysis of capital budget dollars. Planning is currently working with other city agencies to close data gaps and strengthen the equity analysis.

Data from a preliminary equity analysis of capital budget dollars. Planning is currently working with other city agencies to close data gaps and strengthen the equity analysis.

Smith’s position came about after two years of internal discussions at the planning department that trace back to March 2015. That month, there was an optional staff training on racism in the food system inspired a group of around a dozen in the department to begin meeting monthly to discuss Baltimore’s racial legacy and how to fix it. The group became known as the planning department’s Equity in Planning Committee.

The next month, Freddie Gray died while in custody of Baltimore police officers. It added urgency to the internal discussions, which eventually resulted in an equity action plan, with five goals for the planning department.

“Because it was very democratic, with no particular person in charge or responsible for it, it took a lot of time to get to anything that was finalized,” says Elina Bravve, a city planner with the department who became part of those early discussions.

The committee decided on an equity lens with four components, with a core question encapsulating how to bring each component into the various discussions that the planning department regularly holds internally, with other agencies, and with others outside city government:

- Structural Equity: What historic advantages or disadvantages have affected residents in the given community?

- Procedural Equity: How are residents who have been historically excluded from planning processes being authentically included in the planning, implementation, and evaluation of the proposed policy or project?

- Distributional Equity: Does the distribution of civic resources and investment explicitly account for potential racially disparate outcomes?

- Transgenerational Equity: Does the policy or project result in unfair burdens on future generations?

“This was a staff driven effort … acknowledging as staff that we inherited a legacy of decisions that have often been inequitable, often decisions from the planning agency itself, and we are in the present grappling with some of those decisions,” says Smith, who came onboard in July, taking on an assistant director position that had been re-shaped to focus on equity.

Leveraging the planning department’s role in the capital budget process is one of the five goals of the equity action plan. Using the data they’ve gathered on where city capital investment dollars have been spent, they can raise the equity question throughout the process. “In real time, we’re working with agencies to think about how you use an equity lens to prioritize capital investments,” Smith says. “They’re having preliminary conversations right now, and I’m introducing myself, reminding them of some of the things we’ve been working on, and extending myself as a thought partner around how equity can be embedded into their budget process.”

In addition to offering herself as a resource, Smith hopes to remind everyone that the planning department itself is going through this same journey of understanding its role in creating and perpetuating racial inequity and how they can all work together to change that pattern. “Having that level of humility in these conversations gives space to have more courageous conversations, because you’re not putting an agency on their heels,” Smith says.

Another equity plan goal: improve and increase the dialogue and connections between the Department of Planning and underserved communities in Baltimore, perhaps by being more thoughtful about where planning takes place within the city. “We know that space is itself not neutral,” Smith says. “Having someone come to the planning agency where there’s not a lot of parking, not quite easy to get into, you’ve already created levels of distance before conversation has even begun.”

Helping to get all that done, Bravve is now Smith’s second in command. “I think one of the challenges is to see whether we can take this beyond the planning department and to see if we can be a model for other agencies thinking about this,” she adds.

“The city has to consistently challenge itself on these issues,” says native Baltimorean Rodney Foxworth. As co-founder of Invested Impact, a nonprofit advisory firm, Foxworth has spent years helping bring an equity lens to philanthropic capital in Baltimore.

“The way that the city develops its budget, where it allocates investment, is telling,” says Foxworth, who recently took on a new position as executive director of the Business Alliance for Local Living Economies, a national leadership network focused on building stronger local economies. “I applaud the city planning department for undergoing that process to unearth those disparities, and I would also offer up that community activists in Baltimore have consistently cited systematic underinvestment in these places.”

In addition to gearing up for Baltimore City’s capital investment budgeting process, Smith and Bravve are looking ahead to figure out how they can bring in more of those community activists and residents into city planning discussions on a more ongoing basis — because if they want more city agencies to invest in communities they’ve long neglected, they want to make sure those communities have a say in those dollars, too.

“Unfortunately I think there’s been a lot of people assuming what communities want without just asking them,” Smith says.

Smith hopes to launch next year, in February, an ongoing working group or focus group around equity, a space where community members can help us improve the planning department’s work. She’s looking also to launch in the fall a resident planning academy for Baltimore residents to enhance their understanding of Baltimore’s zoning and land use scheme, which is about to go through a massive overhaul.

“What city government has done so far hasn’t worked,” says Foxworth. “Why not now do something different? Why not now entrust the community to understand where are there investable projects in their neighborhoods? I don’t doubt that in underinvested communities across Baltimore, there’s infrastructure that the city could plug into.”

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)