The Atlanta Braves are moving to the suburbs. The team’s lease at Turner Field, built for the 1996 Olympics and then converted for baseball, runs out in 2016. Braves President John Schuerholz announced yesterday that the franchise will move into a new $672 million stadium in Cobb County, just north of city limits, the following year.

The move caught fans by surprise. And, as is typical these days with stadiums, it’s about public money. Cobb County will be responsible for $450 million in financing, according to the Atlanta Journal Constitution. What shape that financing will take is still unknown, but newly reelected Mayor Kasim Reed did not mince words.

“We have been working very hard with the Braves for a long time, and at the end of the day, there was simply no way the team was going to stay in downtown Atlanta without city taxpayers spending hundreds of millions of dollars to make that happen,” Reed said in a rare act of restraint toward stadium welfare. “It is my understanding that our neighbor, Cobb County, made a strong offer of $450 million in public support to the Braves and we are simply unwilling to match that with taxpayer dollars.” (To be fair, his hands are tied with the Falcons’ publicly financed $1.2 billion stadium, also set to open in 2017.)

Cobb County residents may feel excited about their new neighbor, but they should really storm City Hall about the promise of financing. Budget shortfalls for this school year cost 182 teachers their jobs, while the remainder of the school district will have five furlough days. At one point, superintendent Michael Hinojosa proposed moving a “large portion” of high school classes online to help close a $86.4 million deficit.

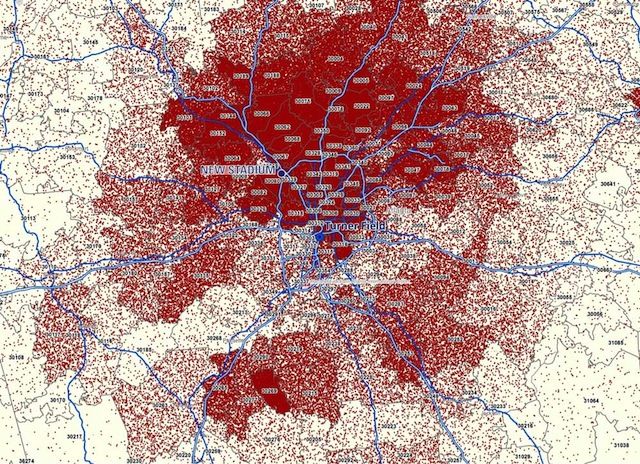

The map below shows that the majority of Braves ticket buyers come from north of the city, where the new ballpark will open. Club officials said in a press release that Turner Field needs upward of $200 million in infrastructure work, like seat replacement and new lighting. “Even with a significant capital investment in Turner Field, there are several issues that cannot be overcome — lack of consistent mass transit to the facility, lack of adequate parking, lack of access to major roadways and lack of control over the development of the surrounding area,” the release read.

Deadspin has a nice chart showing 19 Major League Baseball stadium moves from 1960 up to the Braves’ new home. In the majority of cities — including Houston, which could challenge Atlanta for Sprawl Capital of America — ballparks moved closer to the city center, or just a few blocks away. The Braves, meanwhile, will move 12 miles farther out. That’s not a huge distance, but it’s a symbolic one.

Schuerholz said the decision to move was made in part for transportation concerns, as it will be easier for fans to reach the new ballpark than navigate downtown Atlanta traffic. But Franklin Rabon at Talking Chop raises very real questions about how the new park will handle traffic flow.

The I-75 I-85 connector can indeed be pretty bad during a game day, but as those who live in the area can attest, the I-75 I-285 junction is not substantially better, and it has never had to handle 41,000 Braves fans (rumored capacity for the new stadium). While it is debatable as to whether the transportation situation would be improved in that area as is, it’s unclear what, if any plans, for linking public transportation to the area exist.

We can talk all day about how publicly financed stadiums are a boondoggle and ballparks are poor engines of economic growth. What’s equally unsettling here, though, is the new locale. Sure, the Braves will still have an Atlanta mailing address. But as outspoken Atlanta native and Grantland staff writer Rembert Browne noted yesterday, “Suburbs are where you go to buy multiple pairs of slacks.” Although a team’s allegiances will spread across a region, its heart and stadium belong in the urban core.

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Bill Bradley is a writer and reporter living in Brooklyn. His work has appeared in Deadspin, GQ, and Vanity Fair, among others.