The winter sun is shining as I step into the office of David Gouverneur – urban designer and Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture at PennDesign. Gouverneur gives a wry smile as I look over the stacks of papers piled high on his tables and desks. “At least the sun is out,” he says. “Even if I can’t go outside it’s nice to know it’s there.”

The winter sun is shining as I step into the office of David Gouverneur – urban designer and Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture at PennDesign. Gouverneur gives a wry smile as I look over the stacks of papers piled high on his tables and desks. “At least the sun is out,” he says. “Even if I can’t go outside it’s nice to know it’s there.”

For a man so invested in navigating the intersection between the built, social and natural environments, it’s a telling response. A native of Venezuela, Gouverneur has made a career out of injecting environmental and social values into the process of placemaking. He was kind enough to take some time out of his sunshine and paper-filled morning to share his recipes for healthy cities.

Johanna Hoffman: How did you first come into the design profession?

David Gouverneur: I was interested in design from the time I was 10 years old. I would play and construct things inside my home and out. I’m from Venezuela, from Caracas, and from the time I was little, I was already surrounded by construction, whether it was the things I played with in my house or the construction going on outside in the city.

So through that I started fooling around with the idea of placemaking. I also read a lot of history. I’m from a multi-cultural family – my mother is a second-generation American Jew and my father is African- Venezuelan – so I was exposed to cultural diversity at a young age. In respect to the role of history in placemaking and design, I think that humans, just as they do with cooking, storytelling and art, build things as ways to express themselves. Built environments are reflective of the cultures that create them. There is a power in place and culture, which seeps into architecture. Personally, I’m interested in the former, in placemaking, more so than buildings themselves.

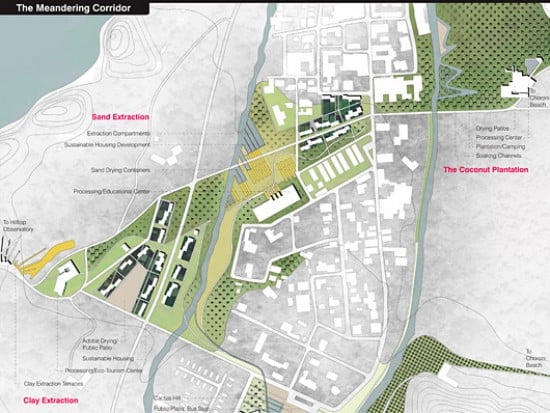

Preservation and Progress: Choroni’s Productive Traverse: The Meandering Corridor (Photo: Marisa Bernstein and Nicolas Koff) – Gouverneur served as Faculty Advisor

What is the role of the designer in society?

As artists, designers are responsible for responding to the cultures they belong to. At the same time, they’re also tasked with taking society to new levels. They must respond to the origins of a society while looking to shape and innovate for the future… But, unlike a painter or sculptor, a designer can’t cut away from a city’s past and start from a blank canvas. A designer’s role is to walk that line between past and future, to take into account the history of a place while providing for the future.

How do you think planning and design inform each other?

That’s an important question. Interdisciplinary work is necessary because cities are so complex. Planners are generally better on issues like policy, economic sustainability, service provision, legal frameworks, etc. But ultimately it’s those issues that largely create urban form! Conversely, if the design of an urban form isn’t successful, improvement of those issues becomes near impossible. So there has to be a strong liaison between these two strengths….. But this is not to say that interdisciplinary approaches lead to lack of distinction in focus. The reality is the opposite — each has to be very strong in what he or she does.

Do you have a conception of the “ideal” city?

An ideal city doesn’t exist. The task of responsible designers is to digest the nuances of individual places. It’s all about creating designs that are appropriate for their contexts. You have to understand place and culture to be able to design.

Still, there are certain challenges that tie us all together. Climate change, for example, affects us all. Availability of water is an increasingly major issue. I’ll repeat what so many others have already said and say that the next major wars will be over water access. So water management and preservation in natural and built environments is something that everyone will have to invest in. Shifts towards greater energy efficiency and food production – these are all issues that will have to be addressed throughout the globe according to the different conditions of each region.

And while doing all this, we still need to bring different cultures together to understand the disparities between us. It’s not about eroding the differences between people and localities but in increasing understanding.

So there is no “ideal” city. But, I will say that generally successful cities have good systems of public space. This means networks of streets and plazas, spaces of human encounter. Good cities place priority on the public turf – those are the places where you can most effectively deal with all the issues I just named – water, energy, etc.

When it comes to designing and improving cities, do you approve of the grid plan, like the one we have in Philadelphia?

In some ways, the grid plan has great value. It’s an open plan. If you need to accommodate growth, you just expand it. It’s flexible and adaptable. It’s been used since Grecian and Roman times. The Spaniards adopted it in Europe and brought it to their Latin American colonies.

In the case of Philadelphia, the grid plan poses pros and cons like everywhere else. The city’s gone through a lot of change – following WW2 it lost over 1.5 million people because of changes in industry and transportation. There was a lot of white flight, people moved out into the suburbs and the whole fabric of urban life changed. But recently that trend has also changed. Center City is a great example – you look at it now and it’s come back to life.

The poor areas in Philadelphia now are the regions that lack economic drive. Neighborhood fabric has eroded, there are increased levels of vacancy, and the grid is full of holes. I think of it like dental work that’s losing teeth. It’s much easier to create new centralities in small compact neighborhoods, like in the barrios in Venezuela or the favelas in Brazil. Those places, which were built much more informally than Philadelphia, are laid more like medieval towns. They’re made up of networks of narrow, winding paths. Most homes can only be accessed on foot. There’s little car access, which means there’s less police access, which makes them hotbeds for drug trafficking. It’s more difficult to retrieve garbage and perform other municipal functions. All this creates a circle of violence and poverty, which creates social tensions that have only been increasing in Latin America.

The challenge for designers in those places is to understand the logic of the formal versus the informal cities, to see where they can come together. It’s about connecting them spatially and conceptually, which is hugely powerful.

But in here Philly, neighborhoods are on a spread grid. So here, when it comes to creating new centralities and reinvigorating a space, I think of applying design interventions like systems of acupressure – in isolated pressure points. This means investing your resources, and community and institutional efforts on specific places that you think are most likely to ‘succeed.’ In the US, there’s available data you can use to do that, data that maps out the lowest crime rates, rates on unemployment, public transportation access, number of vacancies… There’s available data in the US where there isn’t in a country like Venezuela.

What about the impact of civic improvement projects on gentrification?

In the US, unlike in Venezuelan barrios, most people are renters. So any improvements made in most US neighborhoods seem inevitably to lead to gentrification. Let’s take the example of Northern Liberties and the Piazza project. The Piazza project created a new centrality in an extremely run down area. Architecturally, it’s considered a big success. It took advantage of a big lot in an old brewery and created a new centrality, with outdoor movie theatre and markets. It’s also led to a lot of gentrification. So to the old timers there, the Piazza is not a big success – they largely prefer things how they were before.

But there are techniques to deal with gentrification, like facilitation of ownership, asking developers to include subsidized housing, using design and managerial techniques.

So the question is how do we create stronger communities and economies without creating social displacement?

Sounds like a long answer. Like a lifetime’s worth.

It is.