Whenever some depopulated city’s sports team has a remarkable season, crotchety old columnists flock to town and write about how uplifting it is for citizens. Their columns are usually filled with purple prose and mostly untrue clichés. Also: A World Series doesn’t really benefit the people of Detroit or Pittsburgh, it just lines the pockets of franchise owners.

But hosting an annual event, like the Grand Prix of Baltimore, can generate some much-needed tax revenue — so long as the contracts are awarded with an eye for local businesses.

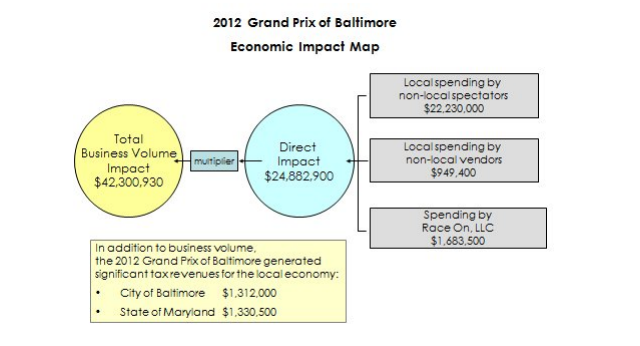

This weekend marks the third running of the Grand Prix, which generated roughly $1.3 million in tax revenue for Baltimore and $1.33 million for the state of Maryland last year. It won’t fill the coffers and tip the scales, but the extra cash is certainly welcome.

That is, if the business stays within city limits. Any time a sports owner or concert promoter talks about the economic impact of a festival or new arena, we need to question the procurement process. Are owners working with local businesses? Are they making sure contracts go to local caterers and construction companies instead of someone from, say, suburban Maryland?

This was my chief concern with the X-Games Detroit bid — which, sadly, went to Austin, Texas — and the economic impact numbers ESPN was touting. I asked J.P. Grant, managing partner of Grand Prix organizer Race On, LLC, if there was a plan in place for local procurement.

“Our local vendors range from our marketing and advertising agency to our ticketing provider and our legal counsel,” Grant wrote in an email. “As a private business, we enjoy the benefit of hiring the best-qualified partners available. Wherever possible, we give priority to Baltimore-based companies and make a significant effort to identify local businesses that can lend their expertise to this endeavor.”

“Wherever possible” is about as tepid an endorsement of local procurement as you can give. That said, I don’t deny Race On’s use of local vendors. It’s clear the company is trying. I understand that businesses operate to make a profit, and that Race On — and, for that matter, every other events coordinator out there — needs to do everything in its best interest to make money.

But I think it’s time for economic impact studies to take a long, hard look at what actually constitutes “economic impact.” There are always readily available numbers — $1.3 million in tax revenue, for example — fed to the press. I’d also like to see analytics firms and experts tell us exactly what they mean by “local.”

There are 28 instances of the word “local” in the 2012 report on the Grand Prix’s impact, which found a 10 percent decline to $42.3 million from the inaugural year’s $47 million. An example: “The local economy is further expanded as the direct business revenue ripples through the economy (referred to a multiplier effect) generating an additional $17.54 million in indirect impact.”

The report goes on to tell us the local spending by non-local spectators, but not to whom they give their money. For all we know, it could be someone slinging hot dogs from well outside city limits.

It’s unfair to put Race On in the crosshairs here. It’s not a villain. But it also isn’t telling us how many local contracts it’s doling out. It would be nice to know how local the impact really is.

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Bill Bradley is a writer and reporter living in Brooklyn. His work has appeared in Deadspin, GQ, and Vanity Fair, among others.