This interview is the second in a series of conversations with friends and members of Living Cities, a philanthropic collaborative of 22 foundations and financial institutions. On September 27th, Living Cities will be hosting a 20th anniversary event with a live webcast available on their website.

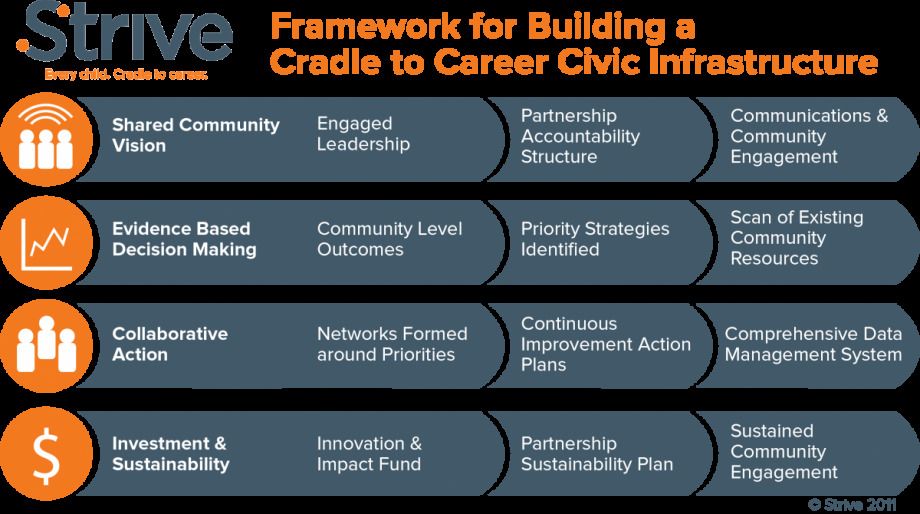

While Living Cities is best known for its work in helping cities overcome their infrastructural, administrative and housing challenges, it also happens to espouse an education strategy that will help cities educate students and create homegrown talent. That model is Strive, a collaborative network of 300 organizations preparing children for success from the cradle until their careers. Founded in 2006 in Cincinnati as a local education reform initiative, Strive is now expanding across the country with participating programs from Texas to Oregon, California to Virginia.

Chad Wick is the CEO of KnowledgeWorks Foundation, which helps redesign urban high schools and supports student-centered approaches to delivering a better education through programs like Strive. He talked with Next American City about Strive’s successes, the need for collaborative leadership and philanthropy as a catalyst for education reform.

How is collaborative action integral to the success of a program like Strive?

For so many decades, our cities were guided by power structures defined by an era of powerful companies. It’s the model best exemplified from the era when the common frame of reference was, “What’s good for GM is good for America.” We relied on corporate leadership to guide not only the well-being of our cities in terms of employment, but in all kinds of development and social well- being issues. It’s a manifestation of the post-industrial reality that new, sustained leadership is not going to come in the form of a group of CEO’s of new companies. The new leadership models have to b) much more collaborative and involve individuals coming from different perspectives — and specifically not just from the business community. This collaborative model is wonderful in that it empowers people who are close to the issues that affect them, but it’s also complex in that it requires everyone to put their own cultures aside for the greater good of the community.

How has the Strive initiative shaped your definition of what good leadership is?

The most acute issue for every city is figuring out how to evolve a base of talent and leadership. It’s not just the school system that has to deliver skilled people; creating talent has got to be everybody’s business. How do we sustain that base of talent in our communities so that we grow the next Einstein? Everything from parenting, health and nutrition down to the way we employ people plays a factor in building the next generation of leaders. So instead of pointing fingers at a school superintendent, Strive brings everyone to the table, helps different organizations see that they have a role to play together in educating children and creating talent, and believes that we must measure effectiveness of these combined actions and continually learn from them and improve.

What role can philanthropy play in changing the education system in cities?

There is that saying that “Those who have the gold make the rules.” There is a bit of that in terms of how organizations and foundations work together. Resources often guide people’s attention and behavior. The advantage of philanthropy is that we can be patient, strategic and aligned. And yet while philanthropy can set some things in motion, it takes the commitment of the broader community to put in the muscle to make their ideas and programs work.

Strive seeks to revolutionize the education system. What kind of timeline does that take — ten years? A generation?

Some would say it takes generations to revolutionize the education system, but we don’t have generations to figure this out. There is a real sense of urgency about this issue among all the people I meet. There are 88 cities around the country adopting or considering the Strive approach; people are willing to set aside their egos if they feel that their collective impact will produce rapid innovation and create a network to share innovative practices in education and overall youth success.

Many people would say cities are more attractive places to live than they were in the ’90s. In terms of education issues, what are the main challenges cities face in the coming 20 years? And what successes do you think cities will be celebrating in 2031?

There’s no doubt our cities feel more livable than they did 20 years ago. But it’s critical to remember that there is still a silent epidemic: most cities are only graduating something like 60 percent of their kids. When you look at graduation rates for minorities, it’s much worse than that. Education is the critical issue for the long-term health of our cities. Over the next two decades, the field of education will undergo a transformation: schools will still distribute core knowledge, but learning will no longer happen only in schools. Everyone, from civic organizations and cultural institutions like museums to commercial enterprises will share in the responsibility of educating students. This collaborative approach makes me very hopeful about our cities; with everyone depending on a successful city, they will have to get off the sideline and get directly into the game. And that will help build a new civic infrastructure.

Diana Lind is the former executive director and editor in chief of Next City.