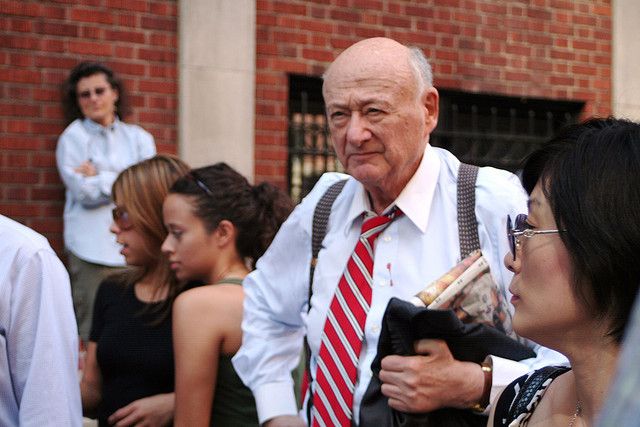

At the inauguration for his first term as mayor of New York in 1978, Edward Koch spoke of the hardships that had plagued the city for more than a decade.

“These have been hard times,” said Koch, who passed away this month. “We have been drawn across the knife-edge of poverty. We have been shaken by troubles that would have destroyed any other city. But we are not any other city. We are the City of New York.”

It was this belief in his hometown’s resilience that led Koch to embark on what many regard as his greatest achievement as mayor: His plan to use billions of city dollars to build and rehabilitate nearly 200,000 units of affordable housing.

Koch’s efforts would go on to revitalize neighborhoods that many at the time had written off as hopeless. His housing plan would be responsible for the construction of 180,000 affordable units across the city, an amazing feat of modern governance. The plan did more than create housing — it gave New Yorkers hope that their neighborhoods could once again spring to life.

Koch approached the city’s problems in a very different way than his predecessor, Mayor Abraham Beame, whose housing commissioner, Roger Starr, advocated for “planned shrinkage” in areas like the South Bronx. “Planned shrinkage” basically meant that the city would cut its losses, pull back investments and services in certain neighborhoods, and hasten population decline. Derelict buildings, and the people that inhabited them, would be abandoned by the city.

Koch had a different vision. Not only would the city continue to provide services, but it would also take the unprecedented step of investing billions of dollars into rebuilding devastated neighborhoods. Most importantly, the new housing would be affordable for low- and middle-income New Yorkers.

But eight years would pass between Koch’s inauguration and the announcement of his Ten Year Capital Plan to build and rehabilitate 100,000 affordable units. Initially Koch had expected the federal government to step up its efforts. In 1978, a visit by former President Jimmy Carter to Caroline Street in the Bronx had lifted hopes that federal dollars were on the way.

But it was soon apparent that the feds were slipping into a pattern of neglect with respect to cities, a trend that continues today. Speaking 30 years later, Koch acknowledges that his housing program was a direct result of this neglect. “[It] came about as a result of President Carter’s refusing to keep a commitment he made to me in 1978 to rebuild the South Bronx, most of which looked like bombed-out Berlin,” he said in 2006.

Koch would have to deal with neglect from future presidents as well. “At its inception, the Reagan administration declared an end to the federal government’s historic commitment to build low and moderate income housing,” he wrote in 1989. “My administration was not immobilized by the federal retreat.”

It took years of pressure from grassroots community organizations before Koch made the decision to use the city’s capital funds. “Koch was a bit late to the game,” says Benjamin Dulchin of the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development, an affordable housing advocacy organization in New York. “But he became a visionary on affordable housing.”

Key to the initial success of Koch’s housing plan was the city’s ownership of 100,000 units of in rem housing, or properties that the city had acquired because of property tax foreclosure. Initially a liability, Dulchin notes that Koch “imagined this housing as the core of his program and put a lot of money and resources into them.”

These buildings were given or sold at low cost to non-profit or for-profit developers. The city then contributed low interest financing and provided tax credits to carry out rehabilitations or for new construction.

Perhaps the boldest aspect of Koch’s plan was the use of the city’s capital funds, unheard of before in city governance. New York ultimately invested over $4.4 billion over 15 years under the programs utilized by Koch. This is a huge sum, and as Koch pointed out, “In fiscal year 1989 alone… New York City spent $740 million in capital funds — more than three and one half times the amount of the local funds expended on housing by the nation’s next 50 largest cities combined!”

In return the city got more than just housing. “The Koch housing program was primarily an economic development program,” argues Jonathan Soffer in his book, Ed Koch and the Rebuilding of New York City. “Koch aimed to rebuild areas devastated by abandonment and neglect into neighborhoods that were viable and self-sustaining without continuing cash subsidies or maintenance expenses.”

A lot of care was used to ensure that building owners would be able to cover operating expenses, and the city used over 100 programs to get the right mix that would allow owners to maintain and repair their buildings. Many of these programs existed before Koch’s Ten Year Plan, but the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development used them with new ingenuity and zeal.

Koch has bolstered his legacy — otherwise tarnished by his handling of the AIDS crisis and race relations — with these housing achievements. Today, once-devastated neighborhoods are thriving. In fact, the issue of housing has swung in a completely different direction: Many New Yorkers now struggle to find places to live that aren’t priced too high. Even as the city strives to create and preserve 165,000 units of affordable housing over 10 years, it loses 10,000 units a year as apartments slip out of rent regulation. In some instances, such as in central Brooklyn, the seeds of Koch’s investments have sprouted gentrification and displacement.

But at his first inauguration in 1978, Koch knew a different city. Speaking at Koch’s funeral last week, current Mayor Michael Bloomberg said:

The New York that Ed inherited is almost unimaginable today: Graffiti-filled subways, miles of abandoned buildings, filthy streets that were unsafe to walk in daylight, much less at night, a municipal government that was broke and had stopped functioning. In the decade before Ed became mayor, we had lost our way. Thanks to him, we became great again. And let me tell you, that was not inevitable. Ed made it so.

It was Koch’s belief that New York could do something about affordable housing, even in the face of neglect from Washington. The city today is a much different place for it.