The Life of an Imaginary Girl, All Grown Up in the Year 2040

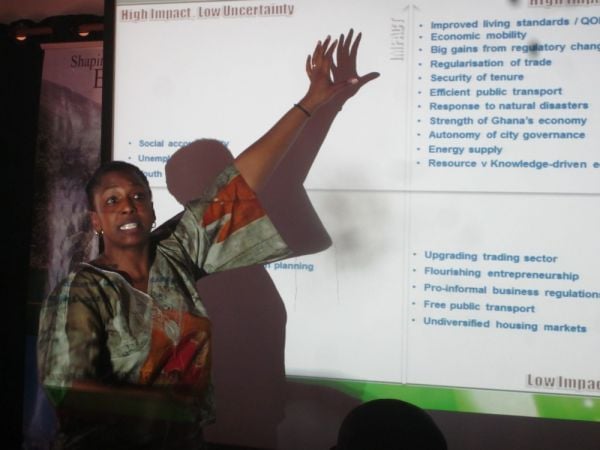

The final scenario group presenting their “play” at the Futures Scenarios Workshop in Accra. Photo credit: Sharon Benzoni

The Rockefeller Foundation’s Informal City Dialogues project recently completed its first series of workshops in all six of the cities participating. In these initial workshops, attendees were asked to participate in developing “futures” for their city. Please click here to learn more about the process, and find out what will take place in upcoming workshops.

“Let’s start making Amina,” Maame Rose said, her voice rising above the debate that had started at the table where she was sitting. Amina was to be an imaginary girl, born in Accra in 2013. The group’s task was to create her future: To imagine the life of this girl in 27 years. The table started buzzing. They decided when she would get married, dreamed of the kind of car she might drive. They were one of five groups of Accra’s citizens, heavily weighted toward representatives of the informal sector, that had come together for the first of a set of workshops to answer the question, “What will Accra look like in 2040?”

The making of Amina and her imaginary contemporaries was the first task in a two-day Future Scenarios Workshop. It marked the beginning, in earnest, of Accra’s part in The Rockefeller Foundation’s Informal City Dialogues. Designed to bring together representatives of the informal sector with business, government and non-profits, the local goal of the Informal City Dialogues is to “explore the forces driving or resisting change…and identify, build or propose an innovation that will help their city achieve a more inclusive and resilient future.” Based on these proposals, Rockefeller will then fund some of the cities’ initiatives.

The first step, however, was to dream.

Even before the dreaming began though, the African Center for Economic Transformation (ACET), Rockefeller’s partner organization in Accra, hosted workshops with representatives of three segments of the informal sector: Informal traders, informal settlement dwellers and members of the informal creative community. In each workshop, participants identified the major issues of importance to them, and began thinking about what they’d like to see in their future Accra. After this, all three groups came together to identify their most critical shared issues, and representatives from each group were selected to attend the Future Scenarios Workshops. Finally, ACET kicked off the project by screening a film about life in one of Nairobi’s slum communities, Nairobi Half Life, which they had dubbed in a mixture of Twi, Ga and English in collaboration with actors associated with Ehalakasa, a local spoken word and poetry collective.

So, last week, inside a room in a small beachside hotel in central Accra, the five groups bent over tables with paper and markers and began creating Amina and others who might people a future Accra. Outside hung a banner quoting Chinua Achebe: “Thinking about the future requires faith and vision, mixed with philosophical detachment, a rich emotional life and creative fantasy as well as the rigorous and orderly tools of science.” Inside, Maame Rose Amudjah, a retired teacher who lives in Old Fadama, presided over the table making Amina. The joyful and smart Sammy, a trader with decades of experience in Accra’s huge Makola market, debated. Abdulai, who works as a kayayo – one of the women who carry items for shoppers in markets in large bowls balanced on their heads — shyly made a few thoughtful observations. Two Rockefeller representatives and one representative from Forum for the Future, another project partner, carefully observed. And bringing with her the science of futures was Geci Karuri-Sebina, a Kenyan futures expert and the workshop’s facilitator.

Geci, the Kenyan futures expert, explaining potential driving factors the group identified. Photo credit: Sharon Benzoni

One group created a future in which e-waste, the health and environmental scourge of Agogbloshie, was not burned but instead processed safely with technology invested in by the government. Another imagined a young man who would find work as a community organizer. Yet another carefully discussed the potential household income of their character. There were some difficult questions. Regarding the low-income indigenous Ga area, a city planner from the Accra Metropolitan Assembly asked, “Do we believe that Jamestown will change?” Some discussed the character of Ga Mashie, another area where many indigenous Ga live — did they want it to be like the wealthy Labone, or something else? How would they preserve their culture?

Dreams prominent in the lives of many in the informal sector quickly came out in the lives of their characters — lucky Amina would receive a good education, funded by money from an oil trust. Slum dwellers in Old Fadama would gain legal status, secure land tenure and a clean, beautiful Korle Lagoon. Public transportation would be efficient (though one woman in this group interjected: “In 27 years, I want my own BMW!”) Somewhat poignantly, others were not so optimistic. One imagined college student would have a great education but no job opportunities when they graduated.

The People’s Dialogue on Human Settlements and the Ghana Federation for the Urban Poor, two of the project partners, helped to facilitate, bringing their enthusiasm, knowledge and language facility (they helped translate much of the proceedings for those more comfortable with Twi and Ga). They also brought their chants. The call I’d first heard on my visit to the Old Fadama susu (savings) cooperative: “Information!” and its response: “Power!” became a kind of refrain that evolved along with the scenario-building progress. “City Changer!” was added, along with its response: “Agents of Change!”

By the end of the two days, another chant was added, echoing the first:

“Energy!”

“Power!”

The group had identified a stable energy supply as one of two major drivers of change in Accra in the years leading up to 2040. The other was standard of living/quality of life. They had reached these conclusions after breaking down issues of relevance to the city’s future, like the use of environment and resources, the legal and regulatory framework, Ghana’s economic situation and distribution of political power. The groups suggested changes like a better taxation system, soundproofing religious centers and building high-speed rail for urban transit. Overnight, the organizers identified eleven such issues that could be the most significant drivers of change for Accra’s future; the participants spent the second morning debating and voting to bring the eleven down to two.

Farouk from the People’s Dialogue on Human Settlements translating the conversation into Twi and Ga. Photo credit: Sharon Benzoni

“Our cultures love stories,” Geci had said at the beginning of the first day. After lunch on the second day each group was gathered around a table, passing around calabashes of candy and creating stories, now narrowed to four scenarios: one best-case, one worst-case, and two in-between. The group that was assigned the best-case scenario soon disappeared mysteriously. When it came time for them to present, they set up their story as a sort of play. “Bring an old woman to tell the story of our country,” they began. “Old lady,” one of them said to Maame Rose, who was playing the role of a wise woman in 2040 who had seen Accra change through the years. “Old lady, can I ask you a question?”

Maame Rose sketched out the story: In the city of Nima (a large informal settlement in Accra) in 2013, things were bad, she said passionately. She rattled off a litany of grievances: no water, spotty electricity, poor education. The residents, she said, came together in a demonstration that sparked real change over the years.

The other scenarios were not so rosy, of course, and served as cautionary tales. Over the next month, Rockefeller, Forum for the Future and ACET will develop the scenarios further, in preparation for the Innovation Workshops, where actionable proposals will be developed.

Still, despite the productivity of the process, questions remain. The creative community part of the workshop was not well attended, resulting in the loss of some significant issues for the creative economy, and raising the question of how representative the workshop participants really were. Some of the abstract and complex terminology in English was difficult for those whose main languages were local or whose education level may not have prepared them for these kinds of exercises. The choice of driving factors seemed, perhaps, a bit rushed: one question that came up was whether “quality of life” is really a driver of change or an outcome of it. Some of the scenarios, too — like relying on street demonstrations to bring about lasting change — seemed unrealistic.

But the process, I was reminded, is an experimental one, and ultimately a beginning for a longer series of conversations. At the end of the day, Sheila Ochugboju, head of the ACET team, thanked The Rockefeller Foundation for the “space to dream.” A couple of days later she told me that she was most happy with the stories within stories, and all the diversity in the room. Abu Haruna, a longtime Old Fadama resident and member of the Ghana Federation for the Urban Poor, told me that the real progress of the day was in beginning a dialogue between the formal and the informal sectors. “In this project,” he said, “it is possible to have eye-to-eye contact.” Most of the time, he continued, officials would not acknowledge members of the informal sector. Now, he says, since they have sat in the same room together, talking things over, he thinks that they should be able to call or visit their offices. “It’s very good for us to be building this kind of relationship. This forum is not about attacking, it’s about what can we do? How can we work together?” He concluded, “We have a saying: We are the problem. We are the solution.”