The Delightfully Weird World of Pirated Video Games

The front desk at the entertainment room, manned by an employee. Photo credit: Joe Keiser

Emerging markets have a way of giving birth to unexpected amalgamations – Beijing’s Obama Fried Chicken, for instance, is a particularly unsettling example. But Grand Theft Auto: Saw, a mashup of the thugs-with-guns video game franchise and the blockbuster torture-porn series may be among the strangest yet.

This is but one of the oddities offered up by Nairobi’s black-market video game industry. In Nairobi, as in other cities not serviced directly by manufacturers, video games are expensive, often priced at around 7,000 shillings ($80 USD) or more. Even before taking disposable-income disparities into account, this is an exceedingly high price for products that typically start at $60 USD — and get discounted quickly — in what manufacturers consider their major markets. This leaves smaller markets like Kenya to importers, who treat games as a high-end luxury product.

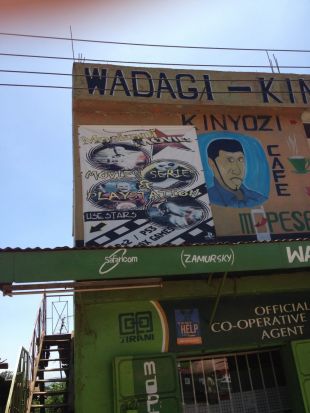

The external façade of an entertainment room in the neighborhood of Kinoo. The room is on the second floor. Photo credit: Joe Keiser

Yet video games are a global, populist medium, which creates a window for the informal market to fulfill demand using a variety of methods. In Nairobi, this includes the proliferation of “entertainment rooms,” small businesses that charge for the use of a television and a video game console like PlayStation 3. While these rooms are typically used to screen bootleg movies, they also turn into game rooms in the afternoon, with players paying two shillings per minute (about two cents USD) and switching off regularly. Not all of these rooms pirate the games they offer, preferring instead to keep a small cache of very popular games designed for short play sessions, like soccer and racing.

But piracy is another way the informal market meets consumer demand for video games. I first discovered Nairobi’s pirated game products at Diamond Plaza, a shopping center well known for its constantly mutating architecture and employment of illegal immigrants from the Indian subcontinent. Here, retailers were selling games for between 250 and 500 shillings (about $3 to $6 USD), depending on how recently they had been released. And as I recently wrote about on the website The Gameological Society, these products can be strange and beautiful to unfamiliar eyes.

The interior of the entertainment room, featuring a relatively modern television and PlayStation 3. The photo was taken during a blackout, which are frequent and hugely detrimental to business. Photo credit: Joe Keiser

While most pirated content is simply direct copies of whatever games are available, many are repackaged with nonsensical box art, like the bootleg Robocop game box flush with rainbows. Others are repurposed with local culture in mind, such as a version of Guitar Hero II in which all the songs contained within have been extracted and replaced with Bahasa rock and rap. And a few, like the aforementioned Grand Theft Auto: Saw and its even stranger cousin, Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas: Kirk Douglas, are crudely hacked into something somewhat new. (I highly recommend a glance at the pictures of these — Ed.) In some cases, this seems like an effort to sell slightly different versions of the same game to repeat customers; in others, it’s hard to fathom what the end goal was supposed to be at all.

What is likely, however, is that most if not all of the hacked content originates outside of sub-Saharan Africa. Preliminary research has traced the possible origins of the content to Brazil, Indonesia and Syria. Though this is largely speculative, it seems likely that video game piracy is an international industry imported by Nairobi, rather than a local industry meeting regional demands. Pirated games are cheap to manufacture, so there’s little risk in applying a “spray and pray” approach to the retail channel, where you just sell whatever product is available anywhere in the world and see what sticks. There are few other plausible explanations for why products so clearly made for other, distant cultures, like the all-Bahasa versions of Guitar Hero II, could appear in this city.

Joe Keiser is a traveling reporter and a contributor to The Gameological Society. Follow him on Twitter @joe_keiser