Lack of Smart Regulation Causes Tension for Thai Masseuses

The author being pulled into “cobra pose” by Mai. Photo credit: Witchaya Pruecksamars

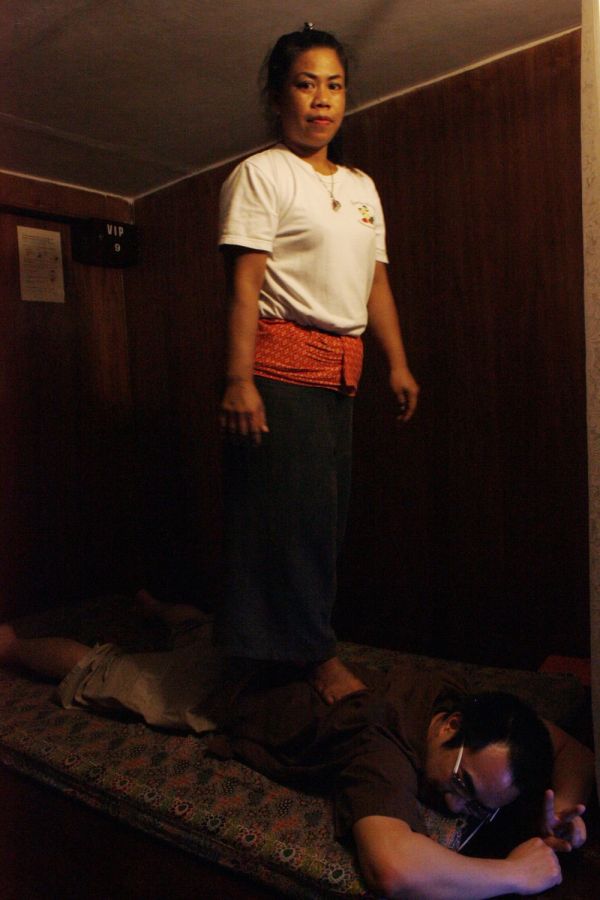

“How are you?” Mai asks, checking that I’m not in pain or unable to breathe. “Good!” I reply in a quick, short breath, a small lungful of air all that I can muster while she is standing on my back with both feet.

With its loudly whirring air-con, fake orchids and wood-veneer wallpaper, the tiny, dingy room I’m laying in doesn’t exactly scream rejuvenation. Yet as the stumpy lady continues to tread carefully on my back with perfect balance, doing a few little hops, using her toes to push down on the muscles along my spine, I can feel all the stress and bad energy dissipating from under my skin. With my face firmly resting on the pillow and my body lying unresistingly on the thin, plasticky mattress, I’m totally at her mercy.

After three-hours of kneading, stretching and twisting — an experience that can end in serious injury when performed by an amateur — I always end up as tender and happy as a Matsusaka cow. I come to Silom at least once a month for this. Mai, 38, has two regulars: Me, and a doctor who works at a nearby hospital. When not massaging a customer, she sits in front of her shop with her gang of masseuses to try to lure in customers. In an area saturated with massage shops, deciding where to find bodily bliss can be difficult. Finding a great masseuse is a godsend – for me, Mai is one of the best.

As a significant player in Thailand’s tourism industry, Thai “traditional massage” can be found in all places, especially where farang, or white foreigners hang out. The authority, of course, is eager to support the practice for this reason, but sadly, they don’t do a good job of separating the wheat from the chaff. (Some may find useful a guide to picking a good masseuse). As such, no one can tell if Mai is any better than the army of masseuses that the Ministry of Public Health churns out, which numbered more than 23,000 last year, plus tens of thousands more that have been trained by other institutions, supposedly totaling in excess of 100,000 altogether. That’s a lot, and they all have some kind of accreditation.

“How are you?” Mai stands on the author’s back. Photo credit: Witchaya Pruecksamars

Mai comes from a lineage of traditional healers. She was informally trained by her mother, also a masseuse, and her grandmother, a midwife and a practitioner of herbalism. Her training started as early in life as she can remember. “They used to trick me into collecting all these herbs and plants,” she says. “I didn’t care back then, but even now I still remember everything.” For more than 15 years, she has been massaging as a profession. Nowadays she works six days a week and usually more than 12 hours a day.

But being skilled and hard-working, unfortunately, is still not enough to get properly compensated.

For the past several years, Mai has been getting around 11,000 – 15,000 baht ($370 – $500 USD) per month. (As a point of reference, Thailand’s newly introduced minimum wage is 300 baht per day). “Nothing is certain,” she says while applying hot herbal massage pack on my back. (“It’s suitable for pregnant ladies and good for the skin,” she tells me). On a good day, she’ll massage non-stop, sometimes with less than one cumulative hour for eating and resting during a 12-hour-plus shift. She often comes to work at 10 a.m. and leaves after midnight. On the occasional bad day, she’ll see only two or three customers, and earn less than half what she usually makes. (She takes home one-third of what the shop charges its customers).

Her choices for the future are also limited. There’s no such thing as a career path for her, though having said this, there are a few routes she could take, some of which she actually has.

Her first option is to diversify her skills (and get more accreditations). She already did this. Mai can now practice Tork Sen (which translates roughly as “to knock on the energy line”) using a wooden hammer and a wedge or stake. I wouldn’t recommend having this done unless you find a masseuse you can really trust — an inexperienced practitioner can crack your pelvis bone with a misplaced knock. Despite all the training she underwent, Mai would make more money if she simply learned nail art, which is what many of her colleagues have done. For one hour of Tork Sen, an incredibly difficult art to learn, the shop pays her 150 baht; for an hour-long session of cleaning and painting fingernails, she could make 150 to 200 baht. But as much as she wants to make more money, she prefers making a living by healing stiff shoulders and tense muscles.

Mai and her smiley manager. She’s been working at the shop for five years and loves her workplace and her friends. “I wouldn’t go anywhere else,” she says. Photo credit: Witchaya Pruecksamars

A second option would be to open her own business. She also did this, selling a piece of land she inherited from her late father and investing all of the proceeds — around 300,000 baht — in her own salon. Sadly, it failed and she lost all of her investment.

Her third option is to go abroad. She hasn’t taken this drastic step yet, and likely won’t because she takes care of a brother who’s crippled from diabetes.

Finally, her fourth option is to quit her job at the shop where she works now (or cut down her hours) so she can work informally, sort of like a freelancer. Although she can provide a more customized service (such as preparing the hot herbal massage pack using 20 to 30 kinds of fresh fragrant plants instead of the ready-made ones) and could potentially charge more this way, doing so would require her to find and retain her own customers, set up appointments and travel around the city – a lot more hassle and risk, in other words.

“I will carry on doing this until I can’t do it anymore,” Mai replies when I ask about her retirement plan. Well, that didn’t really answer the question, but as opposed to having some kind of rosy plan, she chose to convey to me her strong, silent fighting spirit, as well as her commitment to what she does for a living, which is probably a better answer to the uncertainties of life.

The shop where Mai works is one of a few places in Silom where “happy ending” massages are strictly prohibited. Photo credit: Witchaya Pruecksamars

I see Mai as the embodiment of the true practice of Thai massage, compassionate and informal, always accommodating the needs of her customers/patients rather than performing routinized “rhythmic pressing,” which is how the Ministry of Public Health defines Thai traditional massage. From her, I learn that it’s not the techniques that count, but the heart of the healer.

I have had my share of massages gone wrong. One girl who clumsily stepped on my back simply laughed and kept stepping when I told her that I wasn’t sure whether she was trying to heal me or kill me. I also once saw a tattoo-covered male masseuse fall asleep while massaging someone. (He must have been recovering from the previous night out). All in all, I find it somewhat insulting and frustrating that these people make at least the same amount of money that Mai does.

The authority could do a lot to rectify this, but they seem to do just the opposite. Not only do they fail to recognize Mai and other life-long practitioners with informal training, their general inclination to standardize the art also discourages informal practices, i.e. maneuvers and poses other than what are prescribed by the shop owner or recognized by the responsible authority. Forcing these practitioners to follow formal protocols and standards could have a flattening effect (pardon the pun) as authentic practitioners are forced to conform to the generic maneuvers dictated by the formal system.

Rather than an art for healing, Thai massage is often perceived as relaxing entertainment for tourists (not to mention a way to find sexual release). It’s a bit like what’s happened to yoga, which gained popularity in the West as a mere exercise rather than the devotion of mind and body to make one’s self a fitting vehicle for enlightenment (deep stuff).

Believe it or not, Thai traditional medicine and massage were banned by the authority and shunned by those who considered themselves modern (and thus, in some sense, formal) for almost a century. Nowadays, people from all over the world visit Thailand for this experience — an experience that was enriched through informal training and practice. It is only natural that the art be allowed to grow and change, much like the human body itself.