How India’s Landlords, Both Benevolent and Self-Serving, Create Affordable Housing

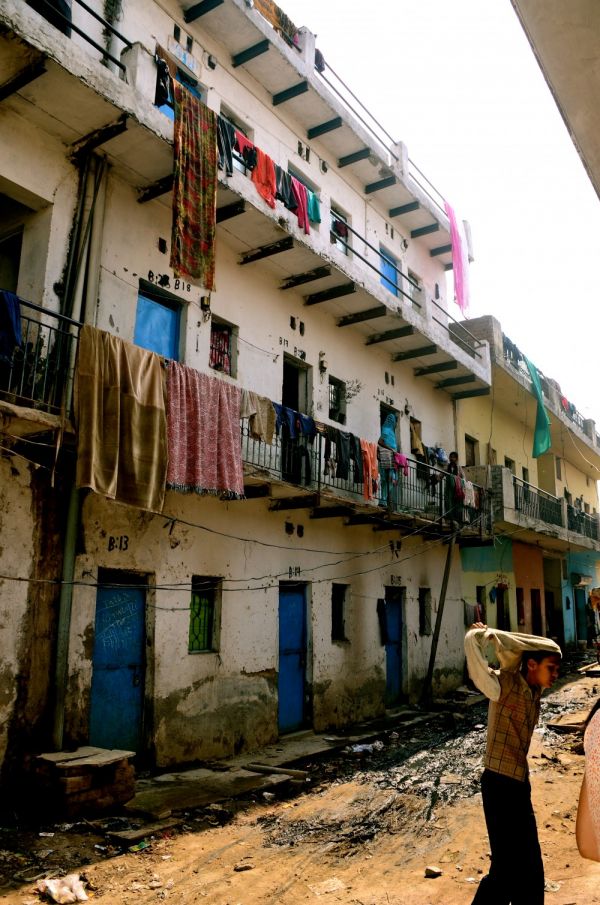

A tenement building in Gurgaon. Photo credit: Mukta Naik

The city of Gurgaon, India is booming. In a guest blog post, architect and urban planner Mukta Naik argues that its local landlords, who provide affordable housing to migrant workers, must not be pushed out by rising costs and a formalizing housing supply.

I agreed to meet Billu outside his grandfather’s samadhi, a memorial that contains a bust to the forefather, clad in black marble and sheltered from the elements by glass-and-aluminum windows. As I followed him down a narrow street we reached a courtyard and crossed it to enter a small room. An efficiently bustling assistant turned on a noisy desert cooler and I was shown a place to sit on a takhat (a seat that’s more like a bed) covered with a crumpled, colorful bed sheet while Billu drew up a chair and sat squarely facing me barely a few inches away.

With sharp eyes, a broad face and an affable smile, Billu is a landlord in Nathupur, one of the oldest and largest villages located on the Delhi-Gurgaon border.

One of 16 cousins in the village who between them own over 500 rental rooms and land worth millions, his simplicity belies his considerable monetary worth. But Billu didn’t acquire his wealth by building and renting out high-end properties on his land, nor does he milk his tenants for every rupee they can afford. In fact, as a landlord in Nathupur, where migrant workers occupy many of his units, he inhabits a role that’s as much benevolent father figure as it is property owner.

Tenements like these provide affordable housing for migrant workers. Photo credit: Mukta Naik

From 1982 to 2003, Billu supplied from his large dairy business, on bicycles, hundreds of kilos of milk to far-off sectors in what is now considered old Gurgaon but were then swank residential areas of the city. After 2003, as the city boomed, he and other family members, like many landowning families who had sold their agricultural land to real estate developers, started building tenements on land they owned within their villages and renting rooms to poor migrant workers from Bihar, Bengal and Uttar Pradesh. Starting with eight units, he has built his business up to some 80 units, all of which he manages personally, selecting tenants, organizing maintenance and dealing with infrastructure-related issues. His assistant, also a migrant from Rajasthan, runs a grocery store on his premises but primarily collects rent and keeps accounts, putting his education and intelligence to good use.

For Billu, these rentals are not a very profitable business. Management costs cut deeply into his revenue; occupancy is never above 80 percent and is often lower. Some tenants abscond the day before their rent is due, he tells me without apparent malice. He describes, with not a hint of derision, the poor hygiene of some tenants and how he needs to repaint and overhaul rooms after they vacate. They waste water and damage pipes and taps. Nevertheless, Billu speaks of them with affection. They know not better, is what his tone implies, and I hear in his voice a fatherly sincerity.

This kind of sympathy for migrant-worker tenants is common among landlords like Billu. In Nathupur, landlords have only recently begun charging migrants for electricity, now that the per-unit rates are too high to provide it for free. But water – the biggest concern in Gurgaon, where the water table falling fast – is still included in the rent. Billu can’t bring himself to charge his tenants extra for it, despite the frequent maintenance needed for submersible pumps and even the occasional tanker that must be called in to augment the vanishing groundwater supply. “They barely have enough money to pay rent,” he says, spreading his broad hands out and shrugging his shoulders. Evicting them or charging more than they can afford simply isn’t on the table.

A migrant worker with his child. Photo credit: Mukta Naik

After conducting extensive fieldwork in Nathupur and other areas of Gurgaon, I know enough about the unequal power structures in villages to understand that Billu’s seeming benevolence actually springs from an immense sense of security and entitlement. As a member of the landowning Gujjar community, who have not only inhabited northern India for centuries but have also been local rulers in the past and are well connected politically, Billu is comfortable on his own turf. His tenants, extremely poor migrants far from their homes, are absolutely no threat to him at all. Yet the relationship between tenant and landlord in Nathupur is not driven by fear. Though migrants are haunted by exploitation and a general loss of identity, most will swear to the compassion of their landlords. In this feudal climate, landlords become patrons and protectors, standing between their tenants and the rest of the village when a dispute arises. Their motivation isn’t charitable – assuming the role of their tenants’ advocate helps ensure they stay in business. There was a time not long ago, after all, when Nathupur was notorious for violence and poor hospitality, and no outsider dared live there. Today, the village landlords are its ambassadors, protecting its improved reputation.

These landlords benefit the entire community. Local villagers are assured of a steady income through rent receipts, while tenants come with low expectations – proximity to work, a roof over their heads and basic amenities is all they ask for (and get). The occasional drunken brawl aside, villagers report that they’re satisfied with this status quo, though I could detect hints of frustration when I quizzed Billu about what alternate business models could work for him. Frankly, he doesn’t see many other options. Landlords like him, contrary to popular belief, don’t have the liquid capital to start new ventures, nor the education or street smarts to bring in investors. They are, in fact, most comfortable in the business of letting rooms. One wizened tau (an affectionate term for old man, literally meaning uncle) in Nathupur joked that they now grow rooms instead of wheat.

For a city that has grown way too fast—Gurgaon’s population grew by 74 percent between 2001 and 2011 and now stands at 1.5 million—landlords in urban villages like Nathupur provide an essential component of affordable housing that the city has failed to plan for. The rental rooms they offer are crucial to ensuring that the low-wage migrant workers who form the backbone of this city have a place to live as they establish themselves.

The landlords, many of them simple folk who have barely travelled outside the district, have instinctively grasped the intricacies of this market demand. Some want to integrate better construction technology into their building practices, using reinforced concrete frames instead of the traditional load-bearing structures, while others aspire to build one-bedroom sets and studio apartments for migrants who work in business process outsourcing and information technology, and can afford to pay more rent.

As Gurgaon continues to grow, it becomes important to ensure that these local landlords aren’t pushed out of business by rising real estate and utility costs or by the growing formal housing supply. Policy makers need to recognize that the flexibility and agility of a rental market in which landlords and tenants can co-exist in a state of mutual dependence might not be replicable in a formal, institutionalized form. In as much as Gurgaon is an example of complex and energetic urban growth in India, the city’s landlordism is a valuable homegrown mechanism that deserves to be recognized and encouraged.

Mukta Naik is an architect and urban planner working to develop effective delivery mechanisms for housing the urban poor in India, with a focus on migrant communities. She is a graduate of the School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi (1999) and did her Masters in Urban and Regional Planning at Texas A&M University (2002).