Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberOn a sticky Friday morning in mid-July, Nuala Gallagher stood inside a chicken run in the back corner of a recently restored community garden in East New York. As a dozen white, brown and black hens strutted about the wood-chipped earth at her feet, pecking at scraps of green, she pointed out the laminated cards attached to the chicken wire, each carrying a comment from a field-tripping first or second-grader. “The chicken coop is an amazing learning tool for children that’s year-round, unlike the garden,” said Gallagher, project director for Cypress Hills Verde, the sustainability arm of a community improvement group.

The hens of Pollos del Pueblo, as the coop is called, will soon start laying nearly 200 eggs per week, all of which are to be distributed free in a neighborhood where a third of adults are obese, the rate of diabetes is nearly double the city-wide average and the leading cause of death is heart disease. “It’ll be a constant source of protein and fresh, organic eggs in a designated-food-desert neighborhood,” Gallagher said.

A wide swath of that neighborhood — nearly 80 individuals — pitched in to fund the coop, with matching contributions from Deutsche Bank Americas Foundation. The financing, all $6,200 of it, came together on ioby, a crowd-funding site for green neighborhood improvement projects that is at the forefront of an explosion of new media innovations for civic improvement.

Generally these tools expand the 311 concept, embrace the crowd or build on government data. Some might connect users directly to their municipal government or enable larger, more complex planning projects, but few match ioby’s polish and potential. Already the site is able to: Increase citizen engagement, particularly in low-income neighborhoods; bring local leaders closer to their community; build reusable networks between neighbors, local groups, city officials, developers and foundations; and track the social and environmental impact of a single project and the citywide impact of all projects.

Short for “In Our Backyard,” ioby boasts a proven sustainability plan and has inspired a slew of copycats. Citizinvestor, which launch this month in Philadelphia with other cities to follow over the next few weeks, offers small-scale government projects for funding by locals. Neighborly, launched this summer by a group of tech entrepreneurs, offers major planning projects proposed by cities and civic organizations. MindMixer, launched last year, also offers city plans for discussion and support from the crowd. All are emblematic of a broader ideological shift away from traditional public financing, as cash-strapped governments, desperate for new ways to generate revenue, begin to see these virtual passes of the hat as a reasonable, even necessary, recourse.

The concept has already caught on among those at the very top.

In April, President Obama signed the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act into law, allowing businesses to raise up to $1 million via crowd-funding sites. The U.S. Department of Energy recently awarded a startup named Solar Mosaic, which plans to crowd-fund solar energy projects, a $2 million grant. And Miami-Dade County just announced a partnership with ioby to use community-devised, community-funded projects to implement part of its long-term sustainability plan.

What ioby, its competitors and even Obama are betting on is a future in which we’ll all be urban planners. You’ll open your city app over morning coffee and get news, traffic and weather as you geo-map a monster pothole and donate to a new charter school proposed by your neighbor with three studious daughters. And look, the transformation of that former meat-packing house on Oak Street into a brewery with a rooftop farm is on schedule, and expected to cut neighborhood greenhouse gas emissions by 12 percent upon completion.

But that day is some ways off, as most of today’s tools are toddlers. Cracking the sustainability code remains elusive, as does reliable government responsiveness on any effort larger than a pothole. And, for the most part, low-income communities remain on the outside looking in.

“A lot of these tools are in their early stages,” said Jennifer Pahlka, founder of Code for America, a program that places freshly graduated programmers inside U.S. City Halls for one-year fellowships. “You’re opening a door and getting people to walk through it, but you have to build out the walls, the rooms, the rest of the house. Still, it’s so powerful coming from a place where the doors had been shut.”

In 1798, the philosopher Thomas Malthus concluded that urban living inevitably led to epidemic and famine. In his “Essay on the Principle of Population,” he portrayed density as an incubator of bacteria and a showcase for human frailty. We now know the opposite to be true. Recent research from Geoffrey West and Luis Bettencourt has found that as a city’s population increases its denizens become more productive, more efficient and better at generating ideas and solving the problems of civilization.

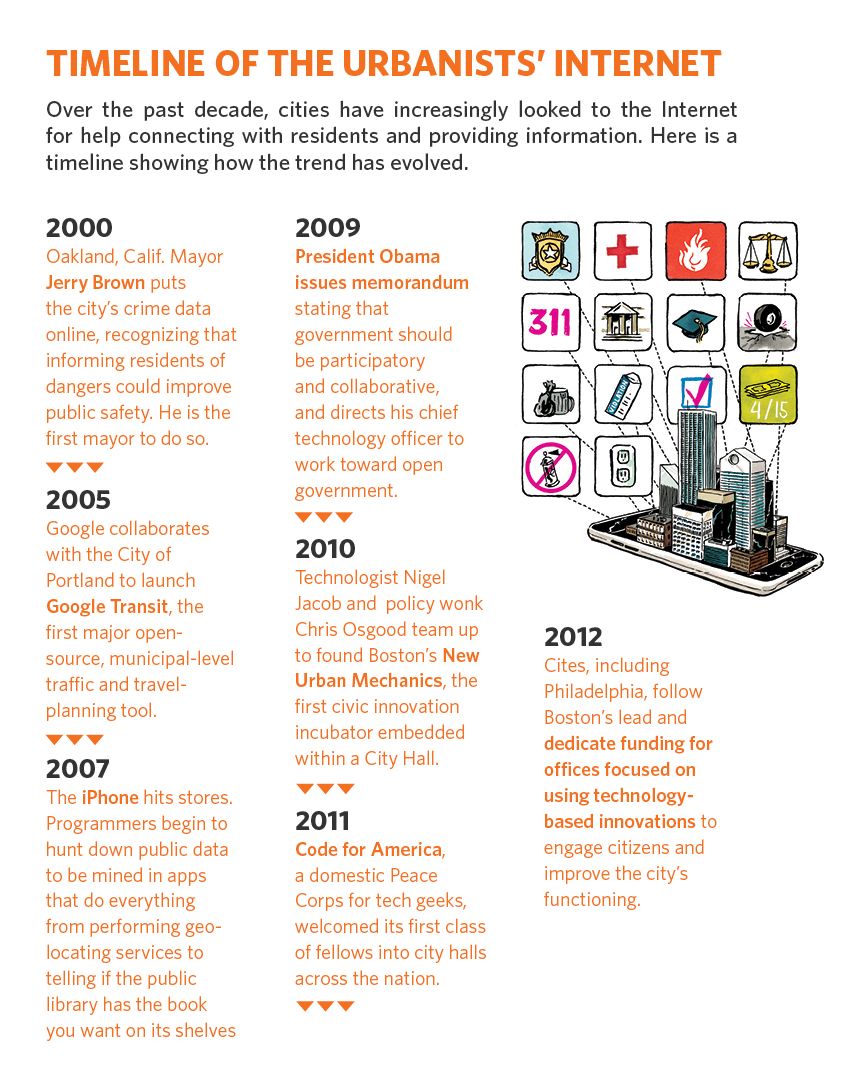

Among the first to appreciate this in the Internet Age was Jerry Brown, who, as mayor of Oakland in 2000, put the city’s crime statistics online to inform residents of danger areas and, ideally, improve street safety. Five years later Google partnered with Portland to launch Google Transit, revealing the promise of the civic-minded open source tool. The 2007 release of the iPhone and the subsequent proliferation and maturity of smartphones vastly expanded the possibilities for mobile engagement and presented the perfect, coder-friendly platform for civic tools: the app.

Governments and young programmers soon jumped on board. On his first full day in office, in January 2009, Obama issued a memorandum stating that government should be participatory and collaborative, and directed his chief technology officer to work toward open government. That same year, Pahlka, then a 39-year-old tech industry executive, came up with her idea for a domestic Peace Corps for tech geeks. Code for America has since created and promoted dozens of civic apps and helped many major municipal governments understand open source and better appreciate the possibilities of technology.

These fellows found that the most difficult challenge in bringing open data to bear is not a programming issue, but a conversational one. In many cases, to create real impact, a tool needs to facilitate two-way conversation — often easier said than done. Chicago, for instance, pushes out data with tools like Plow Tracker, which allows locals to see where city snowplows are during and after a snowstorm, but has no interface to help residents tell the city where a plow is needed. Textizen, developed by Code for America fellows in Philadelphia this year, allows residents to submit input on future development projects via text message. But while the feedback is incorporated into the city’s long-term plan, according to Mark Wheeler of Philadelphia’s planning commission, responders never know the impact of their input. Without that gratification they have little incentive to participate.

“You’re opening a door and getting people to walk through it, but you have to build out the walls, the rooms, the rest of the house. Still, it’s so powerful coming from a place where the doors had been shut.”

The same could be said of any number of tools. IBM’s City Forward offers reams of data to help launch conversations and ideas, but fails to connect citizens to their city. Commonplace is more about building community than connecting citizens with officials to effect local change. Neighborland, a New Orleans-based local projects business backed by Twitter co-founder Biz Stone, is for now little more than an online coffee klatch. “The challenge everyone has right now is closing the loop on public input,” said Frank Hebbert, director of Civic Works at OpenPlans, a non-profit that builds tools for urban engagement. “If you make a contribution to some kind of process as a citizen you don’t necessarily see that resolved or its ultimate impact.”

Quick fixes, such as potholes and streetlight outages, are the exception. For these there are a handful of tools, like SeeClickFix, created in 2008 by entrepreneur Ben Berkowitz. Open the SeeClickFix app or website and report a pothole on a city map, and the system routes your report to the appropriate government department for response. When the issue has been fixed, the user receives an email notification. In 2012, SeeClickFix’s average time to close an issue is 11 days, down from 39 days last year and 100 days in 2010, according to Berkowitz.

It’s an imperfect, if popular tool, with citizen reports up more than 50 percent this year.

It’s also a take-off on FixMyStreet, created in 2007 by mySociety, a UK-based non-profit network of civic-minded developers and consultants. In June, mySociety released FixMyStreet for Councils, an upgrade managed directly by governments that offers FedEx-level issue tracking. Status updates include Investigating, Planned, In Progress, Fixed and Closed.

A few cities are developing these tools internally. New York City has developed more than a dozen mobile apps, including NYC 311. Beijing has partnered with the World Bank to create a platform for citizens to notify the city of problems with biking and pedestrian infrastructure, via the web, social media or mobile app. In early 2010, Nigel Jacob and Chris Osgood founded Boston’s New Urban Mechanics, the first civic innovation incubator embedded within a City Hall. “Government often does a bad job with this sort of thing, not really treating tools like this as products but as government services,” Jacob said. “So we went with more of a product.”

New Urban Mechanics’ most popular product thus far is Citizens Connect, a SeeClickFix-style app that has been downloaded more than 25,000 times since its 2009 release (Boston’s population is about 620,000, according to 2011 census figures). Using the app, a local reports a problem — pothole, nonfunctioning streetlight, graffiti, etc. — then receives an expected response time based on departmental estimates. Importantly, NUM staffers track how often they hit their marks. Some 95 percent of pothole reports are taken care of in the two-day window, according to Jacob, while 75 percent of streetlight outages are fixed in the expected 10 days.

With many cities looking to improve services inexpensively, it’s little surprise that these faster, cheaper 311 tools are proliferating. A 15-city study by the Pew Charitable Trusts in 2010 found that, due to the required phone lines and headset-wearing operators, 311 calls cost a city an average of $3.39. Cities around the world are therefore turning to apps like FixMyStreet, which has been copied in Canada, Germany, Georgia, Korea and Norway, among other countries. The New Urban Mechanics concept is also catching on. The office of Michael Nutter, mayor of Philadelphia, is readying the first NUM franchise. Similarly, San Francisco officials recently launched an internal civic accelerator to mentor and fund local start-ups that use technology to improve government efficiency. The advantage of having an in-house urban mechanic is direct communication between citizens and local officials. “That is really the sweet spot,” said Jacob.

Still, informed observers like Hebbert of Civic Works believe governments need to be more accountable on projects larger than a pothole, like a new stop sign or dog run. “It’s not ridiculous to think we can give people the same level of tracking on small-scale local projects,” said Hebbert.

Good thinking, as it turns out the small stuff is not so small. As Alan Ehrenhalt notes in his new book, The Great Inversion and the Future of the American City, grand public plans often achieve very little, while modest changes can spark significant neighborhood change. Many credit the Chicago Transit Authority’s decision to increase the number and length of elevated trains serving Sheffield, for example, as a driver for the neighborhood’s rebirth.

It’s an unfortunate reality that the neighborhoods most in need of rebirth tend to be those on the far side of the digital divide, which often aggravates the phenomenon. For that reason, many of the latest civic tools aim to reach those who may not have the latest smartphone or spend a great deal of time online. Textizen, an SMS-based mobile phone platform, is one such example.

Another is ioby, which has focused on low-income communities since Erin Barnes founded the site with Yale classmates Brandon Whitney and Cassie Flynn. The trio earned graduate degrees in environmental science, water conservation and climate change, yet also had a good deal of experience with community development and organizing. “One of the reasons we started is because we wanted to bring people who are not part of the environmental movement into the movement,” Barnes said.

Three years after launching in New York City, the site went national in April. So far, it has successfully funded 162 projects totaling over $380,000. ioby claims a success rate of 85 percent, dwarfing Kickstarter’s 44 percent — though ioby defines success as any project that generates enough funding for implementation. Unlike on Kickstarter, where a project’s funding goal must be met within a specific time frame in order for any money to change hands, the final target for an ioby project may, after a late-stage revision, be up to one-third less than the initial goal.

Nearly 60 percent of ioby projects have an explicit social justice goal. Getting these projects off the ground in areas with minimal resources requires strong local leaders, people who know their community and can bring those offline networks online. ioby has found that in addition to being charismatic, caring and inspiring, the best project leaders are collaborative. “If a project has two or more leaders it’s going to be funded six times faster and get deeper involvement from the community,” Barnes said.

Pollos del Pueblo is the child of many parents. Cypress Hills is a small corner of East New York, a sprawling northeast Brooklyn neighborhood with a diverse population and some of the city’s highest rates of violent crime. To improve their community, a group of residents and merchants formed the Cypress Hills Local Development Corporation in 1983. Its spring benefit, this May, raised nearly $40,000. It has provided housing to thousands of local residents, boosted economic activity along key corridors and, working with the city’s Department of Education, opened a community-supported, bilingual K-8 public school in 1997.

The school’s rooftop greenhouse helped highlight the area’s limited access to fresh foods. A group of parents began to rally around the issue and, with help from Cypress Hills, launched the People’s Food Project in late 2010. The two organizations soon eyed a makeover for the community garden on Pitkin Avenue. “One of the things they wanted was year-round use, so we thought of the chicken coop,” said Nuala Gallagher of Cypress Hills’ Verde.

A couple months later, Sam Marks, vice president of Deutsche Bank Americas Foundation (DBAF), saw Barnes make a presentation about ioby at an event for environmental donors, and a light bulb went off. DBAF has supported community development organizations and green projects in New York for years. With ioby, Marks saw a way to link the two. “We’re interested in how community economic development and the transition to a low-carbon economy can be done hand-in-hand,” he said.

Marks contacted Barnes and suggested a matching grant. He then spoke to several development corporations, including Cypress Hills, about funding some of their neighborhood projects via ioby. DBAF soon committed to a $13,000 matching grant for all ioby projects sponsored by New York City community development corporations.

Once Pollos del Pueblo went up on ioby last November, Cypress Hills began to promote the matching grant. “We would send out an email blast saying, ‘Your $5 is worth $10!‘” Gallagher said. “That was really a great tool for fundraising.” The project met its funding goal in April, construction began in May and the hens arrived in early July. They are expected to start laying eggs this month, about two dozen per day, which are given to locals who help care for the chickens.

Deutsche Bank’s matching grant is also funding a green infrastructure project in Brooklyn’s Gowanus neighborhood and a greenhouse in the Bronx, among other projects. If by the end of the year the grant funds have been fully matched by local donations, the bank is likely to make a larger commitment. “A lot of community development philanthropy is premised on the idea that low-income communities don’t have their own resources to bring to the table,” Marks said. “One of the appealing things about ioby is that it has this crowd-sourcing, funding-generation element. We’re hoping more projects will be coordinated and developed with community organizations as part of a broader sustainable community vision, not just a one-off like a local chicken coop.”

Cypress Hills controls six more vacant lots and plans to use ioby again. To further its engagement in low-income communities, ioby is rolling out a text-to-give feature early next year, along with a smartphone app. Other outfits are launching similar efforts. Boston’s New Urban Mechanics is piloting a Spanish-language text-messaging version of Citizens Connect and partnering with the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative, a respected community organization, on an interactive storefront that would be placed in prominent locations and offer transport, jobs and other apps.

Change By Us NYC, a city projects website run by the New York City mayor’s office, awards mini-grants to some of its most needy projects. In May, the Isabahlia Ladies of Elegance Foundation received $1,000 to use their community garden in Brownsville, Brooklyn, to educate the neighborhood about the value of nutrition and healthy eating. “These are the kind of projects we like to boost if we can,” said Robert Richardson, who is the director of strategic technology development for the mayor’s office and leads Change By Us.

The problem, Richardson admits, is a lack of funds. Right now, Change By Us generates no revenue. The mini-grants are funded not by taxpayer dollars, but by grants from the site’s main backers: The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation and the Case Foundation. “As we were digging in and trying to figure out how to achieve our goal of more informed and engaged communities, this seemed like a perfect fit,” said Damian Thorman, head of Knight Foundation’s two-year-old Technology for Engagement Initiative, a Change By Us funder. “It was clear that there was extraordinary power and potential in this space. But we’re very aware that we’re still at the frontier of this work. It’s still very experimental.”

Indeed, Change By Us began life in November 2010 as Give A Minute, created by Local Projects and CEOs for Cities. That initiative asked Chicago residents to contribute ideas, on a website or via text message, about what would make them walk, bike or ride transit more often. It evolved into Change By Us, launched in New York in mid-2011. Code for America fellows then made the new tool open source and, a few months ago, helped launch Philly Change By Us.

Now Buenos Aires is readying its Spanish-language version and Jake Barton, head of Local Projects, expects Change By Us to expand, with help from the Knight Foundation, into three as-yet-unnamed U.S. cities early next year. He’s also adding crowd-funding capabilities to the New York and Philadelphia franchises. That seems to be the civic tech M.O.: Ship a lean tool; incorporate market input into version 2.0; rinse and repeat in other cities, adding emerging technologies as needed. In a few years you’ve got something useful, possibly even sustainable.

The seriousness of that latter challenge is underscored by the plethora of innovation competitions. Code for America’s Civic Accelerator, New York City’s Big Apps competition, TED’s The City 2.0 project and New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s $9 million Mayor’s Challenge are among the efforts looking to nurture the best new urban solutions. Still, a grant or cash award rarely builds a yellow brick road. “We’re learning that it’s really hard for these things to survive,” said Thorman, of the Knight Foundation. Crowd-funding sites have great potential, he believes, as do those linked to government. But Change By Us NYC is part of the mayor’s office, yet still must go hat-in-hand to its foundation sponsors.

We know a community is capable of funding a new bakery or a chicken coop, but can the crowd fund the crowd-funding site? To do so it will most likely need serial project leaders who build strong local networks — people like Tami Johnson. An active resident in the greater Park Slope area for nearly a dozen years, she created one of the first projects to appear on ioby: A cleanup of the lake in Prospect Park. After hitting her funding target of $460, she and a few friends rented pedal boats and pulled trash from the bottom of the lake, including two barbecue grills.

A couple years later, Johnson, who works as a quality assurance manager for a local game developer, convinced the owners of three adjacent vacant lots on Bergen Street to allow her to temporarily use their space for the community. Her ioby project, A Small Green Patch, proposed a 6,000-square-foot vegetable garden that could host concerts, kids activities and other events. After receiving a gardening license from the city, the project quickly reached its target of $4,500.

Johnson recently launched a second, more ambitious phase. The new Small Green Patch project has a $12,000 funding goal and partnerships with several local organizations. An arts group, a mobile urban farming lab and a nearby church are each planning a variety of uses for the space. Johnson hopes to receive full funding soon. Meanwhile, she’s building out the garden and solidifying relationships with local groups, neighbors and the city.

Imagine a Tami Johnson with the resources of a Donald Trump, and you begin to appreciate the revenue potential. Right now, ioby funds its operations via grants from more than a dozen charities and foundations, and receives support from a long list of local businesses. But its long-term sustainability hinges on tips. Upon contributing to a project, each ioby donor is asked to give a 20 percent gratuity. Thus far, three out of every four ioby donors have agreed to the gratuity.

The model has succeeded before. In fiscal year 2011, DonorsChoose covered more than 100 percent of its operating expenses using a similar system, according to a supplement to the Summer 2012 Stanford Social Innovation Review. Considering that DonorsChoose was founded in 2000, and by 2011 had received some $75 million in donations, ioby has a handful of years before it might reach a similar tipping point.

Its latest partnership should provide a boost. Early this year, Nichole Hefty, manager of Miami-Dade County’s Office of Sustainability, was casting about for partners with which she hoped to apply for a local grant. After a staffer suggested ioby, Hefty checked out the site and called Barnes. The county ultimately partnered with ioby and the Health Foundation of South Florida, winning the $65,000 grant from the Funders’ Network for Smart Growth and Livable Communities, an environment and community improvement donor based in South Florida.

“It’s an innovative partnership that will help us engage the community,” Hefty said. “That’s one of the areas where we haven’t made a lot of inroads, but that’s where the good work gets done. An organization such as ioby is a really great way to get into the community and let people know that this is a plan for them and to let them be a part of it.”

The trio will work together to help locals generate project ideas that fit into the county’s long-term sustainability plan, “GreenPrint,” which includes promoting biking, urban reforestation and community gardens. With the first projects going on the site this fall, Barnes hopes to complete at least 20 projects by May. In her view, the crucial factor is that projects are community-led, not force-fed from the city. “We had a pretty explicit conversation with [Miami-Dade officials] about how we don’t tell the community what the project is,” Barnes said. “It’s very likely that the projects will fit inside the ‘GreenPrint’ plan, but we won’t make them.”

This is in stark contrast to Citizinvestor. On that site, a city government posts a project, often in the five-figure range. Citizinvestor, which receives a 5 percent transaction fee only when a project wins full funding, then launches geo-targeted promotions and ads to spark donations. As an example project, Raynor likes to cite the problematic stairs of one New York City subway station, which had been built incorrectly and kept tripping unsuspecting commuters. It’s a clear and simple example, yet underscores the potential problems of this model. Some people may not take kindly to being asked by their government to pay for a project that their tax dollars should have paid for in the first place. It’s akin to SeeClickFix in reverse.

Jeff Friedman, manager of civic innovation and participation in Mayor Nutter’s office, in Philadelphia, supported the creation of Textizen and helped franchise Change By Us and New Urban Mechanics. On September 12, Citizinvestor launched with Philly as its first pilot partner city, and Friedman said he’s not worried about potential backlash. “People understand the problems in the national and local economy and how that’s impacted local budgets,” he said. “We’re interested in experimenting with crowd-funding to see how it works and if we can use it to fund smaller dollar projects to start.”

Crowd-funding larger public projects, such as Neighborly’s $10 million Kansas City streetcar proposal, could pose an even bigger problem. If such a project were to succeed it would undoubtedly be hailed as a triumph. But it might also lower our expectations of government. “I think these models are very effective, very impressive, but they also scare the pants off me,” said Ethan Zuckerman, director of the Center for Civic Media at MIT, referring to sites that crowd-fund public projects. “In the long run they could end up shrinking what we expect from our governments. You end up with systematically underfunded governments and individuals picking up the slack, so that neighborhoods with money are the only ones that get things done.”

Few would portray Glyncoch, a small former mining town in Wales, as a place with money. In fact, Glyncoch officials had been trying to build a community center for years, but had failed to rally the necessary $1.2 million, despite considerable local support. The project looked set to die until it was posted on Spacehive, a London-based crowd-funding site focused on urban planning, early this year.

It soon became a minor cause célèbre. The local community hosted fund-raising stunts, like a sponsored silence of the town loudmouth, attracting media attention. Celebrities like Stephen Fry stepped in to support the project, drawing contributions from corporate sponsors such as Tesco. Glyncoch met its funding goal in April (though only a sliver of the total — about $47,000 — was raised via Spacehive) and the community center is set to open next month.

“I think these models are very effective, very impressive, but they also scare the pants off me.”

Launched in the UK last March, Spacehive is the brainchild of Chris Gourlay. While covering architecture for London’s Sunday Times, he noticed that a small cabal of designers, developers and city officials generally controlled the urban planning sphere. Spacehive is meant to upend that paradigm, giving input and even a measure of control to the people whom the project will impact most.

“The process of trying to bind communities together allows you to get a significant sense of how much buy-in you have,” said Gourlay, who hopes to expand abroad. “A lot of councils we’ve spoken to really like the idea, in part because it takes projects out of their hands, takes away the risk. They can simply back off when it becomes clear that there’s very little community support.”

After nine months, it’s impossible to know whether Glyncoch is the exception or the norm. Thus far, only three Spacehive projects have completed their funding periods (one more is now in fundraising, with a half dozen on the way, according to Spacehive staffers) and all were successful (the community center, an exhibition on rebuilding the riot-ravaged Tottenham neighborhood, and a giant replica of Queen Elizabeth’s head, costing 377 pounds, that was floated down the Regents Canal for the Diamond Jubilee celebration in June).

As on ioby and other sites, anyone can propose a Spacehive project. If the idea receives strong community support, the project creator takes it to a designer, architect or other collaborator, addresses zoning issues and other red tape, and submits a detailed plan for review. Spacehive staffers then verify the project’s viability, confirm planning commission consent and move the project to funding, which can last as long as a year. Because Spacehive projects are, like those on Kickstarter, all or nothing, project leaders are encouraged to set the lowest possible funding target.

Spacehive has a liaison inside the British government and strong connections at Design for London, the city’s planning office. It is also part of a thousand-member business group that supports social enterprise. If and when they choose to fund a project, Spacehive allows major institutional funders — governments, foundations, possibly businesses — to impose additional reporting requirements, such as periodic feedback on the project’s social or economic impact.

Nick Grossman, a visiting scholar at MIT’s Center for Civic Media, sees partnerships between cities and crowd-funding sites as crucial bellwethers. “It’s going to be really interesting to see how government can work with that sort of network, can support more services like ioby, because it delivers considerable leverage and creativity,” he said.

Few are better placed to assess the progress of this space. Grossman helped create and led the Civic Works program at OpenPlans for nearly six years. He is the executive director of Civic Commons, a clearinghouse for civic tech tools, and an advisor to Code for America. In the years to come, he envisions Urbanism 2.0 tools taking on larger, longer-term civic issues, like a major redevelopment project or a bill wending its way through the legislature. “We’re getting better at the smaller stuff,” Grossman said. “But there’s still a tension between doing what we can do and attacking what’s really important at heart.”

Jacob, of New Urban Mechanics, echoes this view. “If all we’re doing with these technologies is finding a quicker way to fix potholes and ignoring the hard issues, we’re not really affecting anything,” he said. “Cities are about those core issues — education, healthcare and safer, better streets. All these point-and-click mechanisms should be aiming to build trust, build networks and really take on the tough problems.”

In a May 2010 paper for Polis, Brian Davis, an architecture professor at the University of Virginia, and Peter Sigrist, of Cornell’s city planning department, lay out their ideal new civic tech tool. Transparent and secure, it would bring together the best local leaders and community groups and engender broad-based funding and buy-in, much like ioby. It would offer engagement tools like Citizens’ Connect or OpenPlans’ shareabouts and the infinite design capabilities of the Open Architecture Network.

One might add the resources and know-how of foundations and the business community and the heft and political skill of city officials, with constant feedback and opportunity for input.

Such a tool could start with small-scale projects — a bike rack, a chicken coop — and slowly expand, refining its processes, moving up to an arts center and finally a transit extension or a new clinic. It could also fund temporary uses, like musical events, parklets and pop-up markets (Kickstarter was born in part because a New Orleanian had wanted to hold a concert). The final step would be connecting across cities, so that a resident of Tuscaloosa could learn about a successful trolley project in Toronto, and reach out to its leaders. The end result would be an international network of the finest tools, practices and solutions for rallying communities to build everything from a stop sign to a High Line.

“If all we’re doing with these technologies is finding a quicker way to fix potholes and ignoring the hard issues, we’re not really affecting anything.”

It’s ironic that after decades of developing means to avoid our neighbors — hedges and fences, locks, garages and security systems — technology looks set to help us reconnect. Yet new tools are popping up every day, and the millennial generation, probably the most civic-minded since the days of FDR, is likely to keep pushing the envelope. Still, some patience is required. For starters, translating the tech-speak of Coders for America into the bureaucratese of civil servants and straining that into the do-gooder language of foundations and environmentalists takes time. “Those circles have been separate and are now inching closer together,” said Grossman. “I imagine a slowly converging Venn diagram of hackers getting educated about how cities work and people in cities getting educated about how technology can help.”

Further, investment for social good is miniscule compared to the funds being poured into for-profit technologies by the likes of Google, Facebook and IBM. This space is dominated not by the lords of venture capital but by tinkerers and tech geeks, environmentalists, civil servants and Coders for America. Lastly, innovation is a messy, fits-and-starts business. To keep moving forward, officials and developers mustn’t “get addicted to the quick win,” as Jen Pahlka puts it. Building extensive networks that improve planning and city services, particularly in disadvantaged communities, takes time — and failure. Much of what we’re seeing now is fast, cheap and minimally useful.

Thus far, crowd-funding seems the best way to organize people, rally resources and enable local projects to affect change in cities. By next year we’ll likely have more than a dozen such tools at our disposal. Neighborland and Popularise, a D.C.-based company that crowd-sources development projects, are said to be considering a crowd-funding element. Patronhood is set to debut soon, as is Fundrise. There’s also Brickstarter, a well-considered effort from the Finnish Innovation Fund, and Civic Sponsor, which is open-source and focuses on public goods like schools and green infrastructure. Most are generally incapable of funding large-scale development (ioby’s largest successful project to date totaled $8,000). But that may not be a bad thing. After all, DIO urbanism (do it ourselves) is no replacement for government action. Municipal bodies should continue to take the lead on major planning projects, with crowd-funding sites — which inevitably work better in wealthier neighborhoods — filling the gaps.

Yet ioby does offer another, longer-term advantage: the power of metrics. For each project, staffers track the total volunteer hours, involvement of neighbors and the community’s change in perception about public space. They also track the number of trees planted, pounds of waste composted and open acreage protected, among more than a hundred other eco-metrics.

By next fall, Barnes expects to be able to extrapolate the collective environmental impact of projects in a specific urban area and, a few years later, to present specific data on how a certain project is equivalent to such-and-such level of reduced greenhouse gas emissions. “They’re going to be able to show at a city-scale how small-scale efforts add up to something really big,” said Hebbert, of OpenPlans. “It’s a funding network but also this monitoring network for successful strategies with metrics for total impact.”

Some project consequences are impossible to measure. Back at Pollos del Pueblo, the comments from first and second-graders hint at a generational shift. A girl named Brooklyn said she wants to be a veterinarian; another, Jocelyn, proclaimed, “Chickens need to eat healthy so they don’t get fat and can’t walk.”

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

A freelance journalist and editor based in Istanbul, David Lepeska writes about Islam, technology, media, and cities and sustainability, and has contributed to The New York Times, The Economist, The Financial Times, The Guardian, Metropolis, Monocle, The Atlantic Cities and other outlets.

Alex Lukas was born in Boston in 1981 and raised in nearby Cambridge. With a wide range of artistic influences, Lukas creates both highly detailed drawings and intricate Xeroxed ‘zines. His drawings have been exhibited in New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, San Francisco, London, Stockholm and Copenhagen as well as in the pages of Megawords, Swindle Quarterly, Proximity Magazine, The San Francisco Chronicle, The Village Voice, Philadelphia Weekly, Dwell, Juxtapoz, The Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, Art New England and The New York Times Book Review. Lukas’ imprint, Cantab Publishing, has released over 35 small books and ‘zines since its inception in 2001. He has lectured at The Maryland Institute College of Art, The University of Kansas and The Rhode Island School of Design. Lukas recently partnered with the The Borowsky Center at The University of the Arts in Philadelphia to produce an eight-color offset lithograph as part of the 2011 Philagrafika Invitational Portfolio. His work was also recently acquired by the West Collection as part of the 2011 West Prize. Steven Zevitas Gallery presented an exhibition of new works on paper this spring. Lukas is a graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design and now lives and works in Philadelphia.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine