Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberOn a recent Friday evening, D.J. Trischler is settling into an IPA and talking about climbing mountains. It’s only 30 minutes after the end of the workweek, and the Flying Squirrel Bar in Chattanooga’s Southside neighborhood is packed. At one booth, some of the city’s leading architects gossip. A small pack of women whisper amid the music as their eyes scan the room. Guests at the LEED-certified hostel next door, where outdoor enthusiasts rest their heads, are settling in. Down the street people finish up productive days at Camp House, a former artist studio-turned-coffee shop and venue where, under clerestory windows, Chattanooga’s entrepreneurs talk potential partnerships.

Eight hours earlier, the bespectacled 29-year-old freelance graphic designer and Pittsburgh native was among them, meeting with potential clients and coworkers about projects. Trischler’s work on co-creating Chatype, the country’s first municipal font, helped him make a name for himself.

Trischler pops Sriracha-tinged falafel sliders as he talks about the city he adopted as his home six years ago. He loves it here and wants to stay, but not everyone can. He clips off the names of friends and colleagues, both Chattanooga natives and transplants, who have left over the past few years. Maybe they found an opportunity that wasn’t available here, or were ready for another challenge that this mid-sized city of a little more than 170,000 couldn’t deliver.

“You know Jimmy Webb, right?” Trischler asks our server, a bearded outdoorsy type.

“Of course,” he responds, obviously aware of the acclaimed climber.

“Why did he leave Chattanooga?” Trischler asks.

“Because he climbed everything,” the server says as he whisks away our plates.

“And that’s why talented creatives leave Chattanooga,” Trischler says.

Chattanooga’s Southside neighborhood is home to such businesses as Camp House, a former artist studio-turned-coffee shop and venue where D.J. Trischler meets with potential clients and coworkers.

It was, in a way, too perfect. In the last few decades, Chattanooga has been riding high on the steady wave of favorable national press that comes with transforming itself from the poster child of pollution into a postcard-perfect downtown, strongly pushing small-business incubators, start-ups and, most recently, building its own gigabit Internet network. New residents, including upwardly mobile young families, have flocked to the city’s center and to growing neighborhoods on its periphery. The student population at the local branch of the University of Tennessee is overflowing. Volkswagen churns out Passats from its first U.S. manufacturing plant since 1988. Amazon has a distribution center. Bands that used to bypass the city now play to as many as 1,700 people in Track 29, a former ice skating rink behind the convention center where the famed Chattanooga Choo Choo resides. Outside Magazine readers voted it “Best Town Ever” for its wealth of outdoor opportunities. And Mayor Andy Berke is a young, ambitious leader who appointed Chattanooga’s first innovation officer and is importing wonky crime-reduction strategies that get airtime on NPR.

Chattanooga is in the midst of a boom. So what happens next? How does the city, after stemming population loss and attracting new homeowners and businesses, stabilize the growth? How does it grow from the kind of city that attracts residents with low rent and a hip vibe to the kind of place that retains residents with good schools, plenty of jobs and safe streets?

“The candy-coating, bright and shiny, attracting things wear off over time,” says Mike Lake, CEO of Leading Cities, a research center formerly based out of Northeastern University. Its predecessor organization, the World-Class Cities Partnership, conducted a study researching talent retention and attraction in the greater Boston area. Lake and company found that after seven years in the region, people had basically established roots and stuck around. “What you want to do is not give them reasons to leave,” says Lake, who is now running for lieutenant governor of Massachusetts. Those reasons are basic: The place should be safe, the schools decent and the housing affordable.

It was November 2012, and Daniel Ryan had options. The 36-year-old Florida native had spent more than a year helping President Obama get elected to his second term. As director of front-end development for the campaign, Ryan oversaw the design for online tools that helped raise hundreds of millions of dollars, register voters and more. That entry alone on his resume could have propelled him to Silicon Valley. But four days after the votes were counted, he was back in the city he loved.

“To me, it was the fact that this is a place someone could come in with an idea and get something accomplished,” says Ryan, who now consults for non-profits and progressive groups.

Caleb Ludwick, a 41-year-old design writer, first came to the Scenic City for college and has moved back twice. In February, he politely declined an offer to join a respectable design firm in Chicago. In addition to the lure of the mountains and a more affordable home, he was compelled to stay by the opportunity to create a niche for himself in Chattanooga’s tight-knit design community.

“In Chattanooga you can be a big fish in a small pond,” says Jim Russell, a Richmond, Va.-based geographer who writes about migration. “I saw there was major ambition in Chattanooga. Because Chattanooga was open, small, actively revitalizing, it created opportunities that you’d have in no way in Boston or the Mission District in San Francisco.”

Ask boosters in town, and they’ll tell you that young people like Ryan and Ludwick are flocking to the city. The numbers, too, show that the city has been gaining more people than it loses. In 2005, it recorded its first population net growth in several years, mostly due to evacuees from Hurricane Katrina. The trend continued. According to U.S. Census estimates, about 17,000 people moved to the greater Chattanooga area between 2007 and 2011. Many of these newcomers were young people, according to researchers at the University of Wisconsin and the National Institutes of Health. Hamilton County, which encompasses Chattanooga, saw a gain in population among 20-29 year olds throughout the 2000s. Though the spike in millennials was not nearly as high as in Fulton County, which includes most of Atlanta, and Travis County, home to Austin, it reflects many of the same trends that have transformed those larger Sun Belt cities.

What Austin, Atlanta and Chattanooga have in common is a recent history of massive investment in their respective urban cores. In Atlanta, millions of dollars in public and private cash has been spent building bike lanes and more walkable streetscapes, as well as turning abandoned rail corridors surrounding the urban core into the Atlanta Beltline, an award-winning $4.3 billion loop of parks, trails and transit surrounded by mixed-used development. Since the late 1990s, Austin has marketed its homegrown musical culture and, like Chattanooga, turned its waterfront into a popular public space.

But an open question in all these cities remains: Once we lure the talented migrants, what do we do to keep them?

“The candy-coating, bright and shiny, attracting things wear off over time.”

Tiffanie Robinson runs a program in Chattanooga focused solely on this problem. WayPaver, a project of a local venture incubator called LampPost, aims to lure tech and design talent from across the country to Chattanooga. Formally launched in January, its strategy includes helping newcomers become part of the community rather than simply view the city as a place with a job. The group partly does this with a beta program that helps subsidize professionals’ downtown rent for a year.

“Over the last several years I’ve watched people move here for a job and then leave,” Robinson says. “There seems to be an issue of getting great talent here and getting them connected to the community.”

In a city like Chattanooga, which has no major Fortune 500 employers like Dell in Austin or Delta in Atlanta providing a local career ladder to climb, people like Robinson face the double challenge of attracting residents and then helping them build their own professional trajectories. Ryan, the former Obama developer who also serves as a resident technologist at WayPaver, notes that “one of the things we hear a lot from local candidates is they feel like they lack mentorship here.”

Like WayPaver, the New Orleans-based business incubator Idea Village has a mission to attract and retain talent. After 14 years of supporting emerging entrepreneurs, CEO Tim Willamson has found that people lured to cities for work ultimately need to feel like they’re a part of something greater. “For talent to stay in a city they need to be connected,” Williamson says. “And they need to be engaged in the future of the city. What we do is to look to make the links from the talent into the existing leadership and partner them with envisioning the future of the city.”

No matter how great a city is or how connected people are to it, not everyone will stay forever. Williamson calls the migration of talent a “natural churn” and says people who leave New Orleans are just as valuable as those who stay, because they become advocates for the city.

Tiffanie Robinson tries to lure tech and design talent to Chattanooga through the WayPaver program.

Russell is also a sort of brain drain mythbuster. His Twitter feed is a fount of news about migration trends, and a forum of debate where he and other academics discuss the latest “dying cities” or regions emerging from a slumber. He says that governments’ fixations on stopping brain drain by building the latest bait to trap creative talent is misguided and fails to understand how people move. Cities, he argues, should realize that creating jobs and focusing on economic development won’t stop brain drain — which, after all, is a natural part of all economies. He points to the state leading the country in domestic out-migration: New York.

“No one thinks it’s the most terrible place in the United States,” he says. “People move there and deal with horrible living situations. The economic opportunity is so compelling that people make themselves absolutely miserable and put themselves in economic and financial peril.”

In the case of Chattanooga, like New York, out-migration isn’t necessarily bad. During his most recent trip to the city, Russell noticed that many people he met had returned to Chattanooga from somewhere else. According to IRS data he reviewed prior to our conversation, Chattanooga “churns” its talent primarily with Atlanta. People may leave the city for Atlanta, where they “refine” their talents, make a name for themselves, and then return to Chattanooga. In some cases, they might venture to Nashville.

“When you’re trying to plug brain drain, you’re essentially trying to economically handicap your local graduate,” Russell says. “It’s like telling them to not go to college. ‘Don’t go because it means you’ll leave. And if you leave it means this place is dying. And then I’m sad.’”

But making sure that the city doesn’t lose the young people it’s worked hard to attract is important, says Josh McManus, a consultant (and Next City Vanguard) who co-founded a Chattanooga non-profit CreateHere that helped professional development and training aspiring business owners, offered grants to relocate artists in the urban core, and surveyed community residents during its five-year span. According to McManus, the non-profit helped start more than 300 businesses. He recently began experimenting with how to replicate the CreateHere model in Detroit and other cities seeking population growth.

“Cities are not doing their emerging leadership talent retention work,” McManus says. “You get someone who makes it to 65 or 70, they retire, there’s no one competent to take over their roles. You bring someone in from outside. You get fresh ideas — but you lose institutional knowledge.”

There is a story that everyone in Chattanooga will tell you when trying to describe the city’s turnaround. It involves Walter Cronkite. One night in 1969, the legendary broadcaster announced on the evening news that the federal government had declared Chattanooga’s air the filthiest in the country. Decades of manufacturing had left residents breathing smog. The city now known for its beauty had been branded on national television as a smoggy wasteland.

“When I came here there was no civic pride whatsoever,” says Stroud Watson, the architect widely credited for making Downtown and City Center the neighborhoods they are today. “There was nothing about our public realm, the ‘our city.’”

The shuttering of manufacturing and the passage of the Clean Air Act in the following decades, along with some local environmental initiatives, slowly helped abate the pollution. How to convince people to visit and see the changes for themselves, however, was a whole other problem. Slowly, the city began to think about how build a post-industrial identity for its downtown. Local foundations, businesses and elected officials pumped resources into the decrepit area hugging the river. Watson’s design studio at the University of Tennessee-Chattanooga paired up with the River City Company, a private economic development firm, to brainstorm pie-in-the-sky ideas and lead public charretes reimagining the wasteland as a lively public space centered on an aquarium.

A dilapidated yet historic bridge spanning the river was renovated and reopened as a pedestrian bridge. When real estate magnate (and current U.S. senator) Bob Corker was elected mayor, the momentum continued with the rerouting of a state route to clear the way for a river park and public art investments. In the 1980s, when Watson first came to Chattanooga, there were only two places between 15 miles where Chattanoogans could visit the water. Now the city is intimately connected with its river.

The long nights at charrettes and squabbles with developers over design paid off with a downtown where people want to be — even traveling to visit from afar. But the rent in the area and in nearby neighborhoods has gotten pretty damn high. In some cases, there’s not enough places to stay. “Affordability is really an issue for us,” Berke says. “Because we have a desirable downtown with lots of activity, more young people want to be in this area. That causes an affordability crunch. And it’s not just young people. Retirees. Empty nesters.”

“When you’re trying to plug brain drain, you’re essentially trying to economically handicap your local graduate. It’s like telling them to not go to college. ‘Don’t go because it means you’ll leave. And if you leave it means this place is dying. And then I’m sad.’”

Perrin Lance, executive director of Chattanooga Organized for Action, a social justice group, says the group found that more than half of residents renting in the urban core “from the river to the ridge, Hill City to St. Elmo,” are paying more than 30 percent of their income on housing plus utilities. More than a quarter of renters, he says, are spending more than half their paychecks on rent. In 2011, Chattanooga had the third highest rising rents in the country, behind New York and San Francisco, according to a surprising report by real estate research firm REIS.

“Go and check the minimum rent of the condos that are being created, and then you do the calculation,” Lance says. “You end up needing to make a salary that’s out of whack with what the U.S. Census says is the median. Literally, the housing that is being created is not for the people who live here.”

For people making less, the outlook is even grimmer. An estimated 1,200 people are on the waiting list for housing vouchers, according to the CHA. Rents are rising across the city. The result is a place far less economic diversity.

City officials and the development community have proposed several fixes to the housing problem. Berke’s administration is considering a tax break for developers if their projects include affordable housing, and may put up city-owned property for development. He hopes the panel he’s tasked to help bolster downtown will bring in additional ideas. Some developers are starting to explore whether Chattanooga has the market for “micro-apartments” — much smaller, non-traditional living spaces that have been piloted in New York, Boston and San Francisco.

In its most recent plan, the firm River City identified some buildings that it could convert to residential use, according to CEO Kim White. The group is now waiting on the city to return with potential incentive programs to help developers and building owners make the changes. Last September, the new owner of the 11-story Chattanooga Bank Building was weighing whether to follow through on plans to convert it to 74 apartment units or a boutique hotel. And in late March, local non-profit arts advisory council ArtsBuild, with the help of the Lyndhurst and Benwood foundations, announced a partnership with a Minnesota-based developer that specializes in low-cost housing for artists.

Affordable housing is only one piece of the puzzle. As Russell notes, people move to and from places for a variety of reasons. Sometimes it’s wanderlust. Maybe they have family issues. Or they simply found a new job that will pay more, and a similar experience isn’t available in the same place.

Behind the Chattanooga that people see in tourism commercials and news reports is a city with struggling public schools, poverty and concentrated crime. Its suburbs are sometimes at odds politically with the city — an openly gay city councilmember is currently facing a recall effort by citizen activists in the ‘burbs. City officials have high hopes for what the gigabit-per-second Internet could become and say it has created around 1,000 jobs since it switched on, the New York Times reports. But that wasn’t enough to make up for the approximately 3,000 jobs lost during the same period. Crime has dropped somewhat but remains high in impoverished pockets. Forty-four percent of single mothers with children under the age of five live below the poverty line.

A pedestrian on Glass Street, a formerly buzzing East Chattanooga corridor where, today, shop spaces are covered with plywood and surrounding homes sit in the middle of unkempt lawns.

Since taking office, Berke has placed much of his focus not on big capital projects but on making sure basic government works. To him, fine-tuning the operational side of City Hall is just as important as a big legacy project. When I ask if his administration will reemphasize quality urban design, he seems a tad peeved, as if I’m blind to the biggest issue he deals with on a daily basis.

“It is critically important to my constituents that we reduce crime,” he says. “It’s the number-one issue in the city. And it’s the predicate for everything else that goes on. We can build all the pretty buildings we want. And if we don’t have safe streets, no one will populate them.”

“Chattanooga has a burgeoning tourism district,” he continues. “Our crime issue is affecting it. People will not invest in their own homes and neighborhoods unless it’s a place they can see themselves staying over the long run. It’s hard to have your business succeed if people think they might get harmed in that area. It’s fundamental.”

Berke’s most ambitious crime-reduction program to date is the High Point initiative, a deterrence strategy that targets a small number of violent offenders and aims to get them to put down their guns through a process of dialogue. The program works by bringing offenders, community members and federal law enforcement officials together in a conversation about sentencing, alternative sentences and opportunities for the offender. A 2012 study by criminologists Anthony Braga and David Weisburd found that nine of 10 cities using the approach had “statistically significant reductions in crime.”

Just as critical as reducing crime is fixing the city’s troubled schools. Chattanooga and Hamilton County schools merged in the late 1990s, bringing together two distinct districts: One largely African American and poor in the urban core, and one white and middle or upper class in the suburbs. In the following years and continuing until now, educational gaps helped perpetuate what the Ochs Center for Metropolitan Studies, a Chattanooga-based think tank, last year called “a two-tiered society” in the region. “In one of those tiers, children attend successful schools that adequately prepare them for future success,” reads the center’s report. “In the other, children too often fail to break the cycle of poverty.”

“We can build all the pretty buildings we want. And if we don’t have safe streets, no one will populate them.”

As in many places across the country, proximity to higher-performing schools in Chattanooga means paying a premium for housing. Many parents bypass the issue altogether by sending their kids to one of the city’s bountiful choices of private schools. “If we have kids and we want them to go to the best school,” Ryan says, “those schools are $20,000 a year, and there goes the cost of living that benefits Chattanooga.”

In some cities, such as New Orleans, parents in gentrifying areas have pushed to start charter schools meant to serve as “melting pots” of income and racial diversity. In Atlanta, too, parents fed up with lackluster neighborhood schools in newly desirable communities like Grant Park have turned to charter schools. Some argue that the alternatives have kept families in the community, which helped stabilize the areas in question, and that now parents are once again buying into the public school option. In Chattanooga, the Public Education Foundation is in the early stages of creating a program that gives educators the freedom to solve problems themselves. In addition, it has created an intensive, multiyear Teach for America-style course. Mozilla, the open-source tech behemoth, said earlier this year that it would give grants ranging between $5,000 and $30,000 to Chattanoogans who would harness the gigabit to create education or workforce development tools.

“Ultimately, Chattanooga’s renaissance remains unfinished for far too many people, and a renaissance unfinished is one that can be undone,” says Lance, of Chattanooga Organized for Action. “The future success of our city depends upon bridging the gap and connecting poorer communities to the amazing opportunities that exist here.”

Patrick Sharkey, an associate professor of sociology at New York University and author of Stuck in Place: Urban Neighborhoods and the End of Progress Toward Racial Equality, says local governments must first focus on the people who already call the city home.

“Instead of trying to lure or retain a specific type of city resident, cities should focus on making the city livable, safe, enriching and prosperous for all,” Sharkey says. “This means making sure that there are no communities left on their own without high-quality schools and child care centers, responsive institutions, and well-maintained parks and sidewalks. The first step in this process is to take control of public space and reduce crime through steps that involve community residents, community groups and the police together. Once crime and violence are under control, then public spaces become more inviting and public life returns.”

You can find Glass Street roughly four miles from the aquarium, in East Chattanooga. In the early 20th century, this neighborhood anchored by a commercial strip was abuzz with activity. Today its shop spaces are covered with plywood and surrounding homes sit in the middle of unkempt lawns. CHA’s nearby Harriet Tubman housing project, which closed in 2012, sits vacant.

In autumn 2005, Katherine Currin settled into a small bungalow in North Chattanooga, across the river from downtown and the aquarium. The University of the South graduate had settled on Chattanooga before even having a job set up — it was between Scenic City and Asheville, N.C. She wanted a place that boasted a vibrant arts scene and lots of outdoor recreation opportunities. The Alabama native, who now lives in Southside, had watched Chattanooga change over the years and was intrigued.

“I liked the idea of being a part of a community that was evolving and finding a way to be a part of that process,” she says. The people were welcoming and the cost of living was low.

In 2012, Currin and a group of young people were working with CreateHere, nearing the end of its five-year term, began to brainstorm their next project. The group zeroed in on the ZIP code for East Chattanooga, which encompasses Glass Street. When CreateHere ended, they started working on giving a voice and visibility to a part of town that had little of both for two decades.

The first time Currin visited Glass Street she saw many fences and other “structures that separate people and keep them out.” Vacated properties, rundown buildings, litter, broken windows. Sidewalks had fallen apart. There was little if any green space. Some faith-based initiatives had been attempted with projects such as murals, but they weren’t in top condition and there was little to no pedestrian activity.

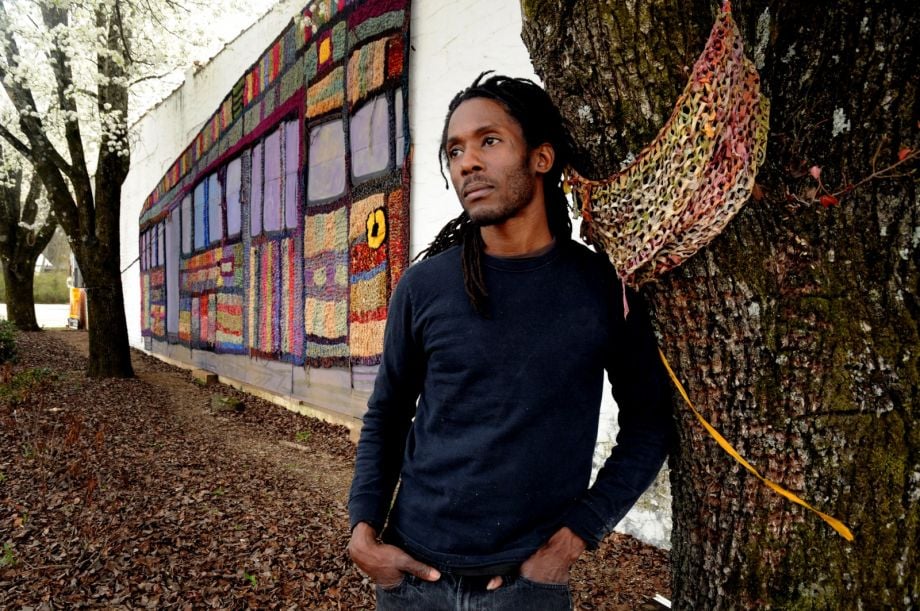

“A pretty dismal picture,” Currin says. Securing grants from Art Place, the Lyndhurst Foundation and an early seed fundraiser of community members, she started working in the neighborhood, using art as a way to bring people together. At first, Currin says, the community was somewhat skeptical — the new Glass House Collective arrived on the heels of promise by a businessman to open a grocery store. (He simply took off without building anything.) But residents have since become engaged. People who never came to community meetings are showing up. Artist-in-residence Rondell Crier, who moved to Chattanooga from New Orleans with his wife after Hurricane Katrina, holds classes in the groups’ offices. Busted-out windows have been boarded up, new sidewalks installed and benches added.

Currin hopes that, by improving the built environment, the collective can help stabilize the neighborhood. Such focused projects in the short term could pave the way for long-term change, leading to reductions in crime, convincing people to walk the streets, and helping build a broader sense of community that, over time, could inspire more people to move to the neighborhood. To prosper, Currin says, Chattanooga needs a variety of housing, neighborhood and lifestyle choices for all its residents — not just downtown newcomers.

Artist Rondell Crier moved to Chattanooga from New Orleans with his wife after Hurricane Katrina.

Chattanooga has grown up and established itself. Now, Trischler says, it needs to move on from the image of a scrappy small town it has crafted over the years. It needs to take risks. It needs to do what he did, which was fail. Last year, the design firm Trischler started with his friend shut down. It was a setback, but one that he’s thankful for. He learned from it. In the wake of the firm’s collapse, Trischler started his own company. And thanks to Chattanooga being Chattanooga, he was able to make it work. You hear this type of story more and more in the Scenic City, where newcomers not gripped to the old narrative about a cleaned-up polluted town are coming to start something. And if things work out, they’re staying.

“We spend a lot of time talking about our reinvention from the dirtiest city to this eco-outdoor destination wonderland,” Currin says. “And I think one of the things that’s hard for us is to embrace the idea of what the city has become. We know how to reinvent but not mature our identity. I think we’re at an interesting crossroads right now, where we need to realize we’ve patted ourselves on the backs enough and it’s time to go to work. We’ve told our story of reinvention time and time again. Now we need to start telling the next chapter.”

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

An Atlanta native who spent nearly 12 lost years in the suburban wilderness, Thomas Wheatley is an award-winning writer who covers transportation, the environment, urban development and state and local politics. A graduate of the University of Georgia and former New Yorker, he enjoys crossword puzzles and C-SPAN. As an award-winning staff writer at Creative Loafing, Atlanta’s alternative weekly, Thomas has covered the Georgia capital’s notorious transportation problems, urban development projects such as the Atlanta Beltline, and the politicians who help decide how the region will (or won’t) grow. He has an intense fear of spiders, clowns and old black-and-white movies in which men court women.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine