Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

A street corner in Seattle’s International District. (Photo by: Bari Bookout on Flickr)

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberMichael Scott misses Seattle. The 39-year-old moved to the city from San Diego in 1996 to be a part of the culture, the nightlife, a place “where everything is happening,” he says. Today, thanks mostly to a brutal commute up and down Interstate 5 each day, he rarely has the time or energy to take advantage of the things that drew him north.

When Scott first arrived he found a one-bedroom house in the Central District neighborhood for $500 a month. In 1999, he started working at Swedish Medical Center as a radiology assistant and moved to a $700-a-month studio apartment not far from the center on First Hill, willing to trade a little extra cost and a little less space for the convenience of walking just a few blocks to work each day. Over the years, his rent started creeping up, as rents tend to do in growing economies. A few years ago, facing down the barrel of a $1,100-a-month studio, Scott decided he could no longer afford the city he loved.

“I felt like I was already making a sacrifice being in a little box. I looked around for one-bedrooms and they were all in the $1,500 range. So my brother and I made a plan to move to Everett together,” says Scott.

Everett is a small city 30 miles north of Seattle. To get to work by 7 a.m., Scott has to get on the road before 6 o’clock each morning. The drive takes at least an hour on the way in and often takes even longer on the way home.

“The commute is miserable,” Scott tells me. “I get home and I have some dinner and I’m just exhausted. The stress of sitting in traffic affects you. I’m off work, but my stress is rising.”

The long drive is impacting his social life too. “All my friends in the city, they’re like, ‘where you at?’ They say ‘can we meet up?’ and I say, no man I’m not driving all the way in.”

Scott’s story is increasingly common in Seattle as the economy booms, rents skyrocket, and middle- and low-income renters get pushed to the margins and beyond.

Mayor Ed Murray wants to change that.

Murray was elected in 2013 on a promise that his experience as a bipartisan dealmaker in the state senate would help him push a progressive policy agenda in the city. Though affordable housing hadn’t played a major role in the mayoral race, once Murray took office it quickly became apparent that the issue was weighing heavily on many of the people who had voted him into office. With local tech behemoth Amazon and other industry titans such as Facebook, Google and Expedia expanding operations in the city and sending construction cranes — and rents — skyward, Murray realized he had to act. Last September, the Mayor introduced a Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda (HALA) and pulled together a 28-member committee of developers, builders, lawyers, urbanists, environmentalists, low-income housing providers and social justice advocates to hash out policy ideas that would drastically increase Seattle’s housing supply. He gave them 10 months.

In July, the committee released a list of policy recommendations ranging from upzones to developer incentives to renter protections.

Supporters say the proposed regulations could be a game changer for affordability and serve as an example for peer cities. Critics say they are coming too little, too late and could even destroy the city they love.

“Seattle wants to be a place where any art student or dishwasher can find a place to live and right now it’s not,” says Alan Durning, executive director of Sightline Institute, a Northwest think tank, and a HALA committee member. “The giant question is whether we can take this promising set of ideas of welding growth to equity and turn it into a political reality.”

By all accounts, Seattle is booming. Buoyed by a strong economy, a growing tech industry presence, hip restaurants, bars, music venues and art, and access to natural beauty like Puget Sound and the Cascade Mountains, Seattle has regularly been among the fastest-growing cities in the U.S. From 2012 to 2013, Seattle was number one, adding nearly 18,000 new residents.

That rapid influx of new people (many of whom are young and flush with the expendable income of a tech salary) coupled with a lagging housing market has helped rents explode. Those young tech workers are also helping raise the area median income (AMI), which is now around $70,000. From 2010 to 2013, Seattle had the dubious honor of largest average rent hike among the 50 most populous U.S. cities, increasing by 11 percent. In 2013, Seattle also slotted into the top 10 for highest rents in the country at a citywide median of $1,117 a month. That median has since climbed to $1,858/month.

As affluent newcomers continue to descend on the city, and expensive new apartments, office buildings (many of them full of Amazon employees), and retail replace the industrial workplaces and dive bars of neighborhoods like South Lake Union, Capital Hill and Ballard, the exodus of residents like Scott grows its own momentum.

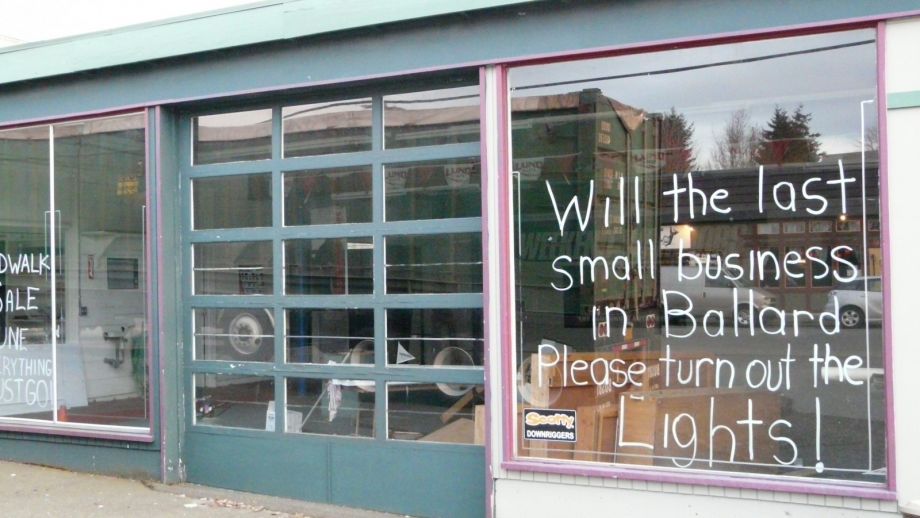

After 51 years in business, Nick’s Boats & Motors in Ballard closed up shop to make way for a tenant more in line with the neighborhood’s gentrifying residential character. (Photo by: Jay Cox)

Over 45,000 Seattle households (one in six) are paying more than 50 percent of their income on housing. Nearly 45 percent of Seattle renters are cost burdened — meaning housing accounts for over 30 percent of their expenses. There are over 3,700 homeless people on the streets in Seattle on any given night, according to the Seattle/King County Coalition on Homelessness.

“If a truly low-income tenant is still here, I can imagine them getting prepared to move,” says Liz Etta, interim executive director of the Seattle-based Tenants Union.

Displacement is notoriously hard to quantify, but because race is an indicator of displacement risk, demographic data can at least provide a glimpse at the problem Seattle faces. The city’s historically black Central District saw significant change from 1990, when black people outnumbered whites three to one, to 2000, when the number of whites surpassed blacks.

Many of those residents who stayed in the city moved to south Seattle’s Rainier Valley, one of the most diverse areas. In 2010, 77 percent of Rainier Valley residents were people of color, whereas they only made up 26 percent of the population citywide. From 2000 to 2010, the number of people of color in Rainier Valley only grew 5 percent, while the white population increased 17 percent. In the small, low-income suburbs south of Seattle, people of color grew 47 percent, while the white population shrank 2 percent.

That population shift is unsurprising given Seattle’s recent fire-hose growth and national trends that are propelling similar movement in cities across the U.S. But as Murray has learned over his first year and a half in office, there are factors beyond the city’s siren song that have made displacement inevitable in many desirable sections of the city. One of them is the mismatch between the city’s land use regulations and today’s needs. Almost two-thirds of Seattle is restricted to single-family zoning, which means there are few places to build the kind of multi-unit development that could relieve some of the pressure on the market.

“The Seattle lifestyle was for decades to live in a bungalow and have your car parked out front and be able to drive to REI and your job at Boeing,” says Durning. “Now it’s changing.”

Before taking over city hall, Murray spent nearly 20 years in the state legislature as a senator and representative. The career politician is a people pleaser, quick to promise initiatives and reforms (some of which he’s already delivered on, notably a $15 minimum wage and bike-share). He’s also known as a short-tempered dealmaker who loves to lock enemies in a room until they compromise and is unafraid to yell at them if they don’t. Both Murrays are in play with HALA.

The Mayor set a goal of creating 50,000 new units of housing in 10 years, 20,000 of which would be rent-restricted affordable units (6,000 units for residents earning less than 30 percent AMI, 9,000 units for residents earning 30 to 60 percent AMI, 5,000 units for those earning 60 to 80 percent AMI). It’s a wildly ambitious goal for a city that’s used to building about 800 affordable units at most per year.

The committee was asked to hash out a list of recommendations for creating more housing and better affordability. Only recommendations with committee consensus made it to the final report.

“It was a 10-month hair pull,” says Durning. “There’s almost no factual claim or a value statement that all 28 people would agree to.”

In the end, they produced 65 recommendations. It is an impressively comprehensive document, especially given the need for consensus among a disparate group. It recognizes the need for building much more housing stock, preserving existing affordability, protecting tenants’ rights, streamlining development, increasing the city’s affordable housing fund, rethinking land use and incentivizing the private market to create more rent-restricted units.

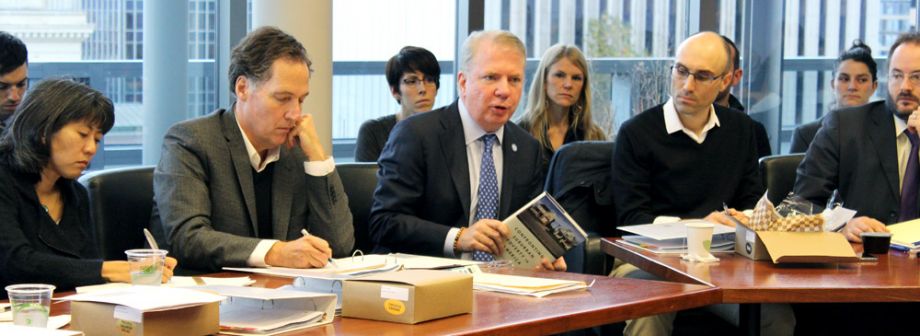

Mayor Ed Murray with Seattle’s Housing Affordability & Livability Committee (HALA). (Photo: The city of Seattle)

Of course, not all 65 recommendations are equally important, nor is it likely that City Council will take on all 65 policies. But, the HALA members say they’re politically salable and that’s critical.

“As policy, the HALA recs are third- or fourth-best options as far as I’m concerned,” says Durning, who helped represent the urbanist bloc on HALA. “But that’s the nature of a 28-person process. What’s exciting about them to me is they have political legs.”

The report highlights eight key recommendations that could have the greatest impact and will likely be the first City Council will consider implementing as policy. The committee recommends a citywide upzone and urban village boundary expansion since the vast majority of residential land is currently zoned for single-family homes. They want the city to build bigger buildings near transit corridors and clear the path for more duplexes, triplexes and mother-in-law apartments in existing bungalow neighborhoods. They want the city to create a preservation strategy to protect existing affordable multifamily homes (especially non-rent-restricted ones) as well as an investment strategy that could help curb displacement.

Funding is, of course, critical, and the report recommends the city create new housing funds through a real estate excise tax and expand old funding sources such as a property tax levy voters approved in 1981 to support the creation of affordable housing. In an effort to reduce cost and barriers for developers, which ostensibly gets Seattle more housing faster, HALA aims to streamline the permitting process.

Most importantly, the report calls for implementing a mandatory inclusionary housing policy and commercial linkage fees. They were the grand bargain around which the HALA committee was able to come together and agree to the rest.

With commercial linkage fees, developers will be required to pay the city a fee of $5 to $17 per square foot of new commercial development. The revenue generated will directly fund construction of new affordable housing.

Torsten North, a project foreman for Turner Construction Company, talks on his phone at the top of a 238-foot high construction crane working on a new building in Seattle’s South Lake Union neighborhood. (AP Photo/Ted S. Warren)

The mandatory inclusionary housing policy will require that 5 to 8 percent of units in all new multifamily developments be rent restricted for residents earning up to 60 percent AMI. In exchange, the city will offer them the option of building an extra 1,000 square feet per floor downtown or in South Lake Union or an additional floor outside of the city core. Theoretically those incentives allow developers to reap more profit from their buildings. Developers will also have the option to pay into the affordable housing fund “in lieu” instead of building on-site.

The mandatory inclusionary policy and commercial linkage fee combo came into the mix after an earlier scuffle between developers and housing advocates who had originally wanted to see linkage fees attached to all residential development (hence the “grand bargain”). Real estate interests, Durning says, “raised a war chest of money” to kill the proposal.

“Our perspective has always been whatever gets us to the most revenue, most units … . But we want to support whatever gets us there quickest. We don’t want to get tied up in court for 10 years,” says Lauren Craig, policy council at Puget Sound Sage, a nonprofit environmental and low-income community advocacy group. Craig’s colleague Ubax Gardheere sat on the HALA committee.

She continues, “Is it a silver bullet? No. Does it combat Seattle’s history of exclusionary zoning? Yes.”

Neither policy is groundbreaking. According to Robert Hickey, a senior research associate at the National Housing Conference’s Center for Housing Policy, a think tank based in Washington D.C., more than 500 cities and towns in the U.S. adhere to inclusionary housing policies, with some dating back as far as the mid-1970s.

Once a primarily suburban strategy, inclusionary zoning has migrated to cities over the last 15 years, with Boston, Denver, D.C., San Francisco, San Diego, Sacramento and, most recently, New Orleans, putting policies into place. Hickey says they are often tied to commercial linkage fees, as is the case in Boston, San Francisco and San Diego.

“The typical policy is built on the same win-win proposition of the grand bargain and has some kind of zoning benefit coupled with affordability requirement,” Hickey explains.

In a hot real estate market, inclusionary policy can get you affordable units and more funding, but Hickey says its strength comes from less objective measurements.

“A lot of cities struggle to distribute low-income housing throughout their neighborhoods,” says Hickey. “There’s been a lot of study of inclusionary housing versus housing choice vouchers and consistently, inclusionary housing programs have succeeded in locating lower-price homes in low-poverty neighborhoods.”

Still, the policies are sometimes criticized for serving middle-income earners and doing little for the lowest-income residents.

“Mandatory inclusionary is one of six or seven important tools. There’s no single policy solution,” Hickey explains.

With a 5 percent rent-restricted unit requirement, Seattle’s policy is expected to provide an additional 6,000 affordable units over the next decade. Hickey is surprised Seattle is setting the requirement so low.

“All of these policies really vary by local circumstance. There is the typical sweet spot where inclusionary policy will require 10 to 15 percent affordability. Seattle’s proposal seems extremely conservative,” he says.

By contrast, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio has proposed an inclusionary policy that would require at least 25 percent rent-restricted units in new buildings.

Seattle’s modest affordability requirement is no doubt a product of HALA’s consensus requirement. Small or not, Durning is excited about its possibilities.

“If you only get more subsidized units by upzoning and when you upzone a share of them have to be rent restricted, that’s a pretty good model,” explains Durning. “It lines up the entire social justice impulse of a progressive city like Seattle behind the upzone coalition, which is small.”

Anyone who has spent any time observing city politics in action knows that policy recommendations, even when they come from a group convened by a mayor, have a way of getting lost en route to implementation. In order for suggestions to become reality, City Council will need to vote for the ideas to become law. Each HALA recommendation will be taken up individually, starting with the controversial commercial linkage fees, over the next several years. Local observers expect the process to only get more contentious. If history is any indicator, Seattle’s many single-family homeowners will come out in force to oppose many of these measures. If they succeed in derailing the process, Seattle will be left with its affordability crisis unresolved and many of its neighborhoods trapped in the amber of prohibitive rents and limiting zoning.

“The staying power of neighborhood groups is extraordinary,” says Durning. “There are a lot of retirees with a lot of home equity and they have nothing else to do but defend it.”

Seattle got a taste of the opposition’s panic and power in early July after a leaked copy of the HALA recommendations made it into the hands of Seattle Times columnist Danny Westneat. He wrote that HALA wanted to upzone Seattle’s single-family bungalows, but failed to mention that the recommendation was to clear the path for more mother-in-laws, duplexes and triplexes everywhere, and taller buildings in the heart of urban villages.

The column set off a wave of hand-wringing media reports and angry calls to council members and the Mayor. By the time HALA actually released its recommendations on July 17th, many of the city’s single-family dwellers were convinced they would soon be living in the shadow of towers and life as they knew it would be irrevocably altered. A few weeks later Murray capitulated and took the single-family upzones off the table.

With City Council primaries just a few weeks after the HALA rec’s release, many worried that fury would lead to mandate-sized votes for certain candidates. Instead, neighborhood preservationist candidates mostly failed to make it to the general, giving HALA supporters a glimmer of hope.

“Most of the candidates who made it through said they’re pro-linkage fee,” says Rebecca Saldaña, executive director of Puget Sound Sage. “I wouldn’t say it’s an equitable development agenda moving forward, but NIMBYs didn’t win.”

HALA supporters are hoping to avoid the same premature death for the rest of the recommendations by organizing a sizable coalition to counteract the anti’s. Lead by Puget Sound Sage and Housing Development Consortium (HDC), the Seattle for Everyone Coalition is extending the unlikely partnerships of HALA. Though it consists predominantly of the social justice advocates, low-income housing providers and unions you might expect, it also has good representation from developers, architects and environmentalists as well.

“For all the time I’ve been working on affordable housing for Seattle and King County, there has been fighting and a lack of trust [among developers and urbanists and affordable housing advocates],” explains Marty Kooistra, HDC’s executive director and a HALA committee member. “Now, through an awful lot of hard work from a small group of people, we’re at a mutual understanding of how to work together.”

That work will mostly involve grassroots organizing among their disparate bases to try and create a formidable pro-HALA block that shows up to council meetings.

“You don’t need everyone marching in the streets. You just need a big enough force. If as many art students and dishwashers show up as there are single-family homeowners, or even half as many instead of just single-family homeowners, I think that’s all it takes,” says Durning.

Seattle for Everyone had its first opportunity to face off with the angry anti-development constituency in early September. City Council held a hearing for general public comment on the HALA recs. Over 60 people signed up to testify.

If previous development-related meetings were any indication it was only a matter of time before a council member was called a Nazi or growth was compared to cancer.

But it seems that this time things were different. There were some choice NIMBY quotes, to be sure, but the fireworks never really came. Even so, there’s little question that HALA will get lots more of that angry opposition in the coming months and years as Council considers its pieces.

But for now, Seattle for Everyone won. The vast majority of testimony was either in favor of HALA or critical that the recommendations don’t go far enough, especially far enough for protecting low-income renters and preserving existing affordability.

And it’s true. HALA falls short when it comes to stemming displacement, arguably the most difficult problem to fix.

“We see it really as a ‘yes, and,’” says Puget Sound Sage’s Craig. “We want to see HALA, but there are many elements that need to happen in order to flesh out a true anti-displacement strategy.”

Craig and Saldaña say first and foremost, an anti-displacement strategy is about engaging and empowering people historically left out of the planning process to shape the development of their own communities. Beyond that, they’re hoping to see equitable development around the light-rail buildout that “includes cultural anchors and affordable housing” and some form of rent control.

“If we just look to large commercial developers and large commercial land owners as a solution, we’re not going to get the outcomes we want,” says Saldaña.

There are some preservation and tenant protections in the HALA recommendations, such as the city dedicating money to its Office of Housing to purchase existing affordable properties and seeking authority from the state to offer tax breaks to landlords if they offer rents below market rate. The recommendations also make some gentle nods to increasing tenants’ rights, but nothing to the extent that might stop economic eviction that comes with the kind of 50 or 100 percent rent increases that Seattle renters now chance. (Seattle currently has no regulations about the amount landlords can raise the rent, so long as they provide 60 days notice.)

Hip, centrally located, and increasingly unaffordable, Capitol Hill is one of the fastest growing neighborhoods in the city. (Photo by Joe Wolf)

At Tenants Union, Etta says her dream program would include both a right of first refusal for a building’s tenants that would allow them to bar the sale of their building and give them time to work with a housing trust to purchase the building, and rent control or stabilization.

“Stabilization is a compromise. Landlords are supposed to be making money, but we need to make sure rents aren’t skyrocketing as high as they are,” Etta explains.

Stabilization, as opposed to stricter rent control, sets a maximum percentage a landlord could raise the rent in a given year to 10 or 20 percent.

That last piece is going to be tough. Rent control is illegal in Washington, and the first step toward getting there would be the state legislature overturning the ban. Senator Pramila Jayapal (who represents southeast Seattle) has vowed to introduce legislation to change that and Seattle Council Members Kshama Sawant and Nick Licata introduced a resolution that would have the Council call on the state to change the law.

But as is always the case, securing affordability and stability for the city’s most vulnerable populations is going to take an enormous effort. HDC’s Kooistra likens it to “standing at the bottom of a mountain.” But the HALA collaboration has left him optimistic about the ability to build beyond the 65 recommendations.

“The seeds are planted for people to think more openly now as opposed to holding posture in their court so they don’t go outside the scope of who they’re suppose to be as battling agents.”

The HALA process is, if nothing else, an excellent encapsulation of the impossible complexity of housing in American cities. The policies will still fall short for many low- and middle-income residents and yet by most accounts, they are as aggressive as they can be while still having a chance of surviving the legislative process.

“As far as policy goes, [the recommendations] are probably as comprehensive as you’re going to find,” says Kooistra.

One need only look 800 miles south to San Francisco to see what’s at stake. That city too is in the throes of an affordability crisis spurred on by zoning issues, a housing shortage, an impulse by existing residents to fight new development and an even larger influx of tech industry wealth. With median rent for a one-bedroom apartment now at an eye-popping $3,460, it is unquestionably a city for the wealthy. It’s little wonder that Seattleites fear becoming San Francisco’s northern twin.

But it’s not too late to prevent that fate. Renting and buying homes in Seattle is still half as expensive as San Francisco. If City Council can pass the most robust versions of the HALA recommendations, if the urbanist and social justice coalition can stand up to NIMBYs’ fear-driven opposition to change, if the city acts fast and resists its historical impulse to hand-wring and dither through endless process, then Seattle can stave off its San Franciscan fate and perhaps once again be a place where the artists and dishwashers and Michael Scotts can afford to live.

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Josh Cohen is Crosscut’s city reporter covering Seattle government, politics and the issues that shape life in the city.

Follow Josh .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine