Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

The side of the road in Gurgaon is a bad place to be if you’re on foot, because there isn’t much of it there. The sidewalks, if they exist at all, tend to be narrow, busted up and blocked by overgrown foliage or random piles of garbage. Pedestrian signals are nonexistent. Everywhere is traffic, which roars and coughs along without pause, surging and blaring and jamming. It churns up a thin mist of dust that coats everything.

Yet here I am, standing like a fool by the side of the road, head scrambled by the noise and an omnipresent sun, on my mobile with a citizenship activist named Vinita Singh. She is somewhere in the river of cars, auto rickshaws, motorbikes, trucks and buses.

She tries to guide me. “Keep going to your right and you should see me,” she says. I look to the right. I see only a wall of trees. She rings off.

Just then, a group of feral pigs runs past me from behind, snorting and tossing their heads. I look ahead and see that a motorbike rider, tired of waiting for the traffic to move, has jumped up onto the sidewalk. He is headed straight for me, followed by another, and another, and another. I am clinging to the narrow peninsula of pavement between the bikes and the pigs when my mobile rings again. “I can see you,” Vinita says. “You just have to cross the road to get to me.”

She is smiling and waving, standing next to her neat little white car. Between us swirl four lanes of two-way traffic. Or five lanes, or six lanes, or none, depending on the way the ever-shifting chaos resolves itself at any given moment.

Once I make it to the other side and jump into her car, everything is, literally and figuratively, cool. The inside of the vehicle is air-conditioned and spotless. I am sweaty and shaken, but Vinita herself has not a hair out of place. Her white kurta is crisp and immaculate.

As she puts the car into gear, I lean back and relax, looking through the window at the people walking along the roadside. I am not one of them anymore.

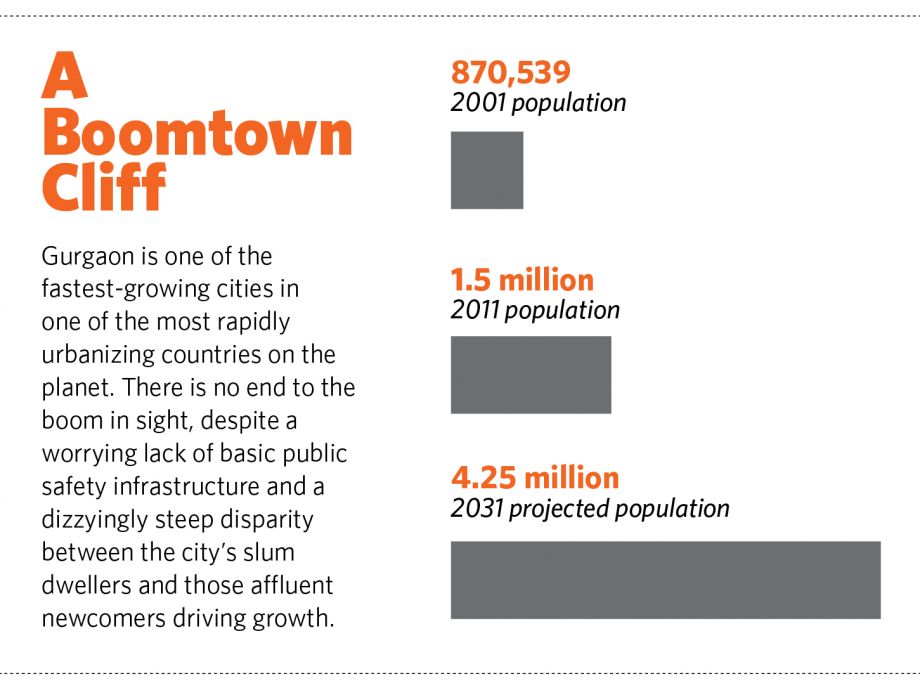

This is the way it is in Gurgaon, India, a suburb of New Delhi and one of the fastest-growing cities in one of the most rapidly urbanizing countries on the planet. It’s growth that has been financed and supervised almost entirely by the private sector. A quarter-century ago, Gurgaon was a village backwater. Now there are 1.5 million people living there, and more moving in every day. The city’s median income is the third-highest in India, and it produces 70 percent of the revenue for the state of Haryana, where it is located.

The roads leading to Gurgaon may not be easy to navigate, but global capital has managed to find the way. In the beginning, Suzuki’s Maruti car plant was the marquee employer here (the brand controls 46 percent of the high-octane Indian car market). Now, 400 of the Fortune 500 are said to have offices in Gurgaon. You’ll find outposts of Honeywell, Konica, Pepsi, Deloitte, Panasonic and pretty much any other brand name you would encounter in the flashing lights of any global city.

Visiting executives can get off the plane at the sleek new Terminal 4 of New Delhi’s Indira Gandhi International Airport, get picked up by a driver and be whisked directly toward Gurgaon on a modern expressway. In a matter of half an hour or so (that is, if there isn’t a hellacious traffic jam, which there often is) they can be checking in to a ritzy high-rise hotel, as well appointed as any in the global business sphere.

If they were to open the windows of those chauffeured cars or pricey rooms, they could smell the cooking fires burning in the slums that fill in the spaces between the skyscrapers, where hotel workers live with their families.

Sandals and cooking utensils topped the list of what of what jhuggi-dwellers needed the most in the wake of a fire that destroyed an entire slum.

Indeed, Gurgaon is all about inside and outside. On the inside — of the cars and SUVs, of the scores of gated communities and office parks, of the high-end malls and five-star hotels and hospitals that cater to medical tourists from abroad — you will find the prosperous “new India.” Everything is peaceful. Everything works. The power might go out for a few seconds or even a minute, but it always comes back on, because there are backup generators that provide electricity at a premium rate. Turn the tap, and water comes out, trucked in from somewhere else. The toilets flush, and the sewage is taken care of, by somebody. Entrepreneurs plot international business moves over high-speed WiFi connections. The garbage is hauled away, even if you don’t know where it goes. The flowers blossom.

On the outside of the windows and walls, the poor and working class sweat it out, facing constant power and water shortages. Outside, people scramble for inadequate and even dangerous transportation, and watch as rising food costs eat away their small wages. Outside, the feral pigs roam free. Gurgaon has come to embody unprecedented upward mobility and economic opportunity, but also gaping disparity and dysfunction.

And yet the city’s Wild West atmosphere, while frustrating and sometimes destructive, makes this a place where just about anything seems possible — even a better, cleaner, safer Gurgaon. The same entrepreneurial energy and openness that has made Gurgaon an international destination is beginning to manifest in the civic realm. Increasingly, ordinary citizens are stepping in to mop up the mess left behind by unchecked development, corruption and lack of planning. People like Vinita Singh — who on the day I met her was on her way to help a group of poor women in an unauthorized settlement to secure food aid they’re entitled to — are no longer willing to be bystanders to a corrupt, ineffectual public realm.

If they were to open the windows of those chauffeured cars or pricey rooms, they could smell the cooking fires burning in the slums that fill in the spaces between the skyscrapers.

Even in the political sphere, which in India is notoriously marked by apathy among the educated middle class, that sense of possibility is inspiring a new generation to wade in and get to work. Nisha Singh is a good example. Singh (no relation to Vinita) is a member of the new city council that was voted in for the first time just last year, but she’s not a career politician and enjoys bucking the stereotype. Her Twitter bio reads, “Contested Municipal Elections. Followed every rule and still won! Now trying to make a difference. Hope to inspire others to take up ethical politics in India.”

She deals every day with constituents who come to her for solutions to the city’s cascade of problems, but hasn’t lost sight of the tremendous energy Gurgaon has to offer. “People love the freedom, diversity and newness of Gurgaon,” she says. “Right now, it’s a love-hate relationship. Fifty percent love it, 50 percent hate it. Someday I hope the balance will tip.”

Tipping that balance is critical not only for Gurgaon’s future but for the future of globally interconnected cities everywhere: Can a place that has become the unwitting model for untrammeled, privately led growth model a new breed of city built by the private sector but shaped by public interests?

There is an ancient Indian proverb that says for a city to come into being, it must have one of three things: An emperor, a river or rain clouds.

Gurgaon gets some rain during the yearly monsoon, but it is a mostly arid place with poor farmland over which rain clouds are a relative rarity. It does not have a river. But Gurgaon does have something a bit like an emperor, in the form of a company called DLF Limited.

DLF stands for Delhi Land and Finance, and it is the largest real estate company in India. Founded in 1946, DLF began by developing land within the capital itself. In the 1970s and ’80s, constrained by land use regulations in Delhi, the company began buying up land in Gurgaon at a bargain price. In other words, DLF made a gamble. A big one. They put their money on the idea that on cheap, dusty, sleepy fields of Haryana State, they could build a new Indian way of life — and that people would be ready to buy.

Smart thinking.

When the Indian economy was liberalized in 1991, opening the way for multinational corporations to invest in the country and for Indian businesses to get their piece of the pie as well, Gurgaon was perfectly positioned. Just 35 kilometers from the center of the capital, but lacking its restrictions on land use, Gurgaon was a blank slate for the dream of a new India. DLF was ready to sell that dream, and as the company correctly anticipated, there were plenty of people ready to buy. By 2007, DLF’s initial public offering stood at $2.3 billion, setting a record for India.

The company’s holdings in Gurgaon now include the 3,000-acre DLF City, which encompasses malls, offices, residential complexes and a golf course, as well as an additional 4,000 acres. But DLF is by no means the only player in town. Many other major interests have entered the booming market: Between 1980 and 1991, DLF received 56 percent of the real estate licenses in Gurgaon; in 2011, it got only eight of 73 licenses issued. Last year alone, between 1,500 and 2,000 luxury housing units went on the market. Some property values in the area have increased 15-fold since 2003.

Ads for the city’s countless housing developments promise “the finest golf lifestyle,” “the last word in luxury living” and “the privilege of ownership.” There are occasional dips in real estate prices, but the market keeps coming back. One luxury housing offering sold more than 700 unbuilt apartments in one day last September. In a nation where even members of the current middle class grew up in a culture of scarcity, Gurgaon offers abundance.

“Gurgaon is like little islands of development, fortified,” says Rwitee Mandal, a young architect and planner who lives and works in Gurgaon. It’s a city she freely admits to disliking, for its lack of street life, its oppressive and contextually inappropriate glass-and-steel architecture, its crazed and dangerous roads.

There is a reason that Gurgaon doesn’t look like a traditional Indian city, and it’s because development here didn’t follow a traditional path. The forces behind the much-touted “Millennium City” haven’t looked to the government for planning and infrastructure. Instead they have built their own, like the soon-to-open, state-of-the-art light rail system that will connect several DLF properties. DLF and all the other developers in Gurgaon have been custom-manufacturing a city for a rapidly growing professional class that wants, and expects, to live in fine style.

There are public costs to the never-ending private development, and one of those costs is safety.

Privately owned and operated high-speed roads have been built without regard to pedestrians who might have to get from one side to the other, leading to dozens of deaths as people make the crossing anyway. In some cases, bridges and underpasses were constructed later, as afterthoughts.

Sexual violence against women is rampant, and the law enforcement response is widely viewed as inadequate. Last spring, the Gurgaon chief of police suggested that the best way for women to protect themselves was not to work after 8pm. Meanwhile, incidents like the gang rape of a 6-year-old routinely grab headlines. Guns are a fashion accessory for many of the town’s high rollers; gun ownership in India is second only to the U.S., and the National Capital Region, where Gurgaon is located, is well known for pistol packing. The newspapers are filled with tales of kidnappings and sometimes-violent extortion schemes. Security, like everything else, is privatized, with uniformed guards standing at all the gates. Gurgaon’s malls, its closest thing to public spaces, have a militarized feeling as a result.

During the monsoon, the streets are often impassable due to flooding. Meanwhile, the water table has been depleted so drastically that as an emergency measure, new regulations have been put into place to prohibit the use of well water for construction. The multitude of wells in the city have often been a deadly attraction for the children of the city’s poor, with a number of them falling to their death in the gaping open holes.

There are public costs to the never-ending private development, and one of those costs is safety.

The fast-paced, completely privatized model of development that Gurgaon exemplifies has led to lots of spectacular construction, but it has also led to some ongoing debacles that affect the wealthy as well as the poor. Take the main toll road that leads to Delhi, which carries 180,000 cars every day. Last August and September, the high court of Haryana temporarily prohibited the private company that runs the road, Delhi Gurgaon Super Connectivity Limited, from collecting the 21-rupee toll because of the congestion that resulted at the 32-lane toll plaza. The traffic there backed up for as much as two hours at a time.

There was plenty of blame to go around. Why is the toll a ridiculously uneven 21 rupees rather than 20? Why isn’t there better enforcement of people who enter the electronic toll lanes but are carrying cash? Is it the fault of the police? Or of the Haryana Urban Development Authority, which awarded the contract to begin with?

The toll plazas were reopened in late September, on promises that problems would be fixed. But the traffic jams immediately started up all over again. The toll plaza was blocked by residents from a nearby housing colony who were protesting the elimination of a U-turn that allowed them to reach their homes. Now the Haryana state government is looking into buying out the private operator in order to end the debacle.

Saurav Adhikari is an experienced corporate executive who lives on a high floor of a swank apartment building, with a fine view and full amenities — pool, tennis court and all the rest. The luxury surroundings, however, aren’t enough to completely shield him from the chaos that defines the city outside of his complex’s walls. And he, like a growing number of his peers, feels a responsibility to work for change.

Adhikari was in the earliest wave of upwardly mobile professionals to make his own wager on the new Indian dream. Back in 1998, when working for Pepsi, he moved to a high-rise in Gurgaon. Builders were still in the early stages of constructing the first malls and golf courses. The sleek metro connecting the city to central Delhi was a future vision. Adhikari was the first resident in his building.

He had been reluctant to consider Gurgaon. “No one ever came here,” says Adhikari, a dapper and gracious man with graying hair. But building a home in Delhi was “impossible,” and financing a purchase of an existing one wasn’t much easier. Adhikari decided to take a chance. “I’m a betting type, a measured betting type,” he says, over a cup of tea. “That’s how I got this place.” And he has watched his investment prove its worth, not just in appreciating value, but in the changing surroundings. “I used to have to go to Delhi for everything,” he says. “But now I don’t need to leave Gurgaon at all.”

Yet the ever-increasing ease of his own life doesn’t erase the chaos he observes in the world outside his corporate-owned mini-city. Several years ago, he decided to channel his frustration with the dysfunction into a non-governmental organization called SURGE, which stands for the Society for Urban Regeneration of Gurgaon and Its Environment. Among other actions, the group has sued the state for improved infrastructure, bringing a public interest lawsuit to the courts. The courts, Adhikari tells me, are a relatively robust civic instrument in India, even if their workings are sometimes arcane and slow.

Through SURGE, he and his colleagues have fought to combat some of Gurgaon’s most pressing problems, working to expose the local government’s sketchy financial dealings and pressing for organized rainwater collection to avoid further depletion of the rapidly sinking water table.

SURGE is just one of dozens of NGOs working to improve conditions in Gurgaon. One of the biggest of these citizens’ groups, I Am Gurgaon, has been instrumental in getting thousands of new trees planted around the city and in fighting to preserve a biodiversity park that provides much-needed open green space at the city’s edge. Another citizen activist, Priya Singh, has been working with local government to improve sanitation across the city and has gotten tangible results. NGOs like Adhikari’s take on all the problems the city has to offer, from the schooling of poor children to the preservation of trees.

Outside of Gurgaon’s gated communities, office towers and high-rise condos, slum-dwellers deal with rising food costs, constant power and water shortages, and unsafe, inadequate transportation.

Social entrepreneurs have been drawn to Gurgaon as well. Surekha Waldia, 34, moved to the city with her husband and young son a few years ago. Like so many her age in the city, she is an entrepreneur, trying to get her piece of the new economy — although she laughingly admits that she and her husband are still renters, having repeatedly missed out on buying an apartment at a price they can afford.

Surekha has developed an educational program she calls ELNA (Experiential Learning via Nature-Based Activity) and is trying to bring it to some of the numerous local private schools. The kids learn about things like recycling, conserving power and water, and the importance of vegetation to a healthy ecosystem.

Surekha has watched the green of Gurgaon disappear as the city has grown up around her. “This used to be all mustard fields and sunflowers,” she says, waving her hand as she drives me down a rutted road with skyscrapers going up on either side. “Within four years, all have vanished.” She jokes that when the city fixes potholes, she no longer recognizes what street she is on, because those are her landmarks.

Then she grows serious. “The environment is getting suffocated, and we are going to see a concrete jungle,” she says. “It’s so important for children to appreciate the problems they see all around them, especially as it relates to the environment. Students have to be prepared for the tomorrow they are going to face.”

That tomorrow is coming not only for the children of Gurgaon, but for all the swelling cities of India and indeed for the entire urbanizing world. Projections for the growth of Gurgaon vary, with one estimate putting the 2031 population at 4.25 million, while others say the number couldn’t possibly go that high. What seems certain is that the privately driven model that Gurgaon represents, where the state takes a backseat in planning and regulation, is badly strained already.

In a September essay for Outlook India, writer and intellectual Gurcharan Das traces the evolution of his own thinking, which has paralleled the transformation of modern India, of its rising middle class and of Gurgaon itself. When he was young, Das had the socialist ideals of the nation’s founders, he writes. Then, disillusioned by economic stagnation, he took a libertarian tack, believing that a laissez-faire approach would let the country and its people thrive. He welcomed the economic reforms of 1991.

Now, with the cautionary example of Gurgaon before him, he has changed again. He defines himself now as a “classical liberal,” newly convinced that a stronger state role is necessary to protect the national interest. Das writes of how India’s central government has always been weak, in contrast to that of China, where new cities are highly planned affairs:

India has historically had a weak state. But it has always had a strong society, and the average Indian has been defined by his place in that hierarchical society. It is quite unlike China, which has had a strong state and a weak society…

Given this past, it is not surprising that after Independence, India went on to become an untidy democracy rather than a tidy autocratic state. And in the twenty-first century, true to character, India is rising from below, quite unlike China whose success has been scripted from above by an amazing technocratic state that has built extraordinary infrastructure.

India’s advantage, Das writes, is its self-motivated populace and the entrepreneurial energy that infuses not only economic life, but also the intellectual arena. India’s advantage, he writes, is its people.

The people of Gurgaon, as talented and industrious as they may be, are laboring under a system of governance that is almost as confusing and cobbled-together as its streets. For years, the city had no elected government. The Haryana Urban Development Authority, or HUDA, an urban planning authority of appointed bureaucrats, was for a long time the only government in charge. Residents have long complained about its sweetheart deals with developers, its lack of transparency and accountability.

Then, in 2008, the city got its own government, the Municipal Corporation of Gurgaon, or MCG. Last year saw the first MCG elections, and 35 councilors were chosen democratically to represent different neighborhoods of the city. The move toward a more functional democracy happens piecemeal; HUDA still has control over privately developed areas. The traditional villages that remain within Gurgaon’s city limits (and those of other Indian cities as well) are exempt from many regulations. Known as lal dora, these lands are meant to be used for the common good of the community. In practice, they are havens for illegal housing, development and businesses. There are few avenues to improve the inadequate infrastructure ostensibly supporting the lal dora.

This mishmash of governance has contributed to a perennial disconnect between the city’s elected officials and middle-class constituents, many of whom have never relied on government for basics like running water and trash pickup.

“In cities, if you don’t have resources to solve problems, you should involve the people.”

The image of the disaffected middle-class voter is an Indian political truism bordering on cliché. Nearly every person I spoke to brought it up. Getting prosperous, urban citizens to vote is a difficult task in India, says Anupam Singh, a software entrepreneur who has worked to increase civic engagement among the middle class. “They are cynical,” says Singh, a meticulously neat man sitting with me in one of Gurgaon’s many Western chain outlets, this one a branch of the British chain Costa Coffee. “They think politicians are there just to make money.” In the last election, Anupam Singh took on the issue directly, campaigning for Nisha Singh (no relation).

Her victory at the polls was not necessarily expected. “People like me almost never win elections,” says Nisha Singh. She explains that the political structure in India is still heavily dependent on caste-based voter turnout, and that the educated elite usually sits the whole thing out in favor of private sector work. “When attempts are made, we almost all the time lose.”

Nisha Singh, who studied engineering in college before receiving her MBA, was working in development and education for the poor when the elections were announced. Sitting in the tastefully appointed living room of her bungalow-style home, looking out onto a green and leafy garden, she explains why she ran against the odds to become one of the 35 representatives in local government.

“When the elections were announced, my simple logic was, here I am,” she says. “I am perfectly capable of doing things.” As a member of the Residents Welfare Association of her housing colony, she had dealt with the authorities about various infrastructure issues, and her work in development had given her additional knowledge about the workings of government.

Since her election, she has worked on a variety of nuts-and-bolts issues — improving roads, laying sewer lines, installing street lights, enforcing laws against advertising roadside liquor shops. These are early days, and the going is slow.

“There’s a lot more I’d like to do, and at a faster speed,” she says, “but I don’t have that ecosystem around me.”

Nisha Singh had to overcome India’s infamous middle-class political apathy to get elected last year as one of Gurgaon’s first batch of 35 councilors.

I ask her about the huge gap between the rich and poor in her city, and whether she sees it as a threat to Gurgaon’s long-term stability and growth. As more of the land is developed for high-income housing, will all but the very rich be displaced?

She sighs and looks down at her hands. “That gap in wealth is there, and probably growing. These people are very much part of the city. I employ four people at my house, they have to live somewhere. The erstwhile villages [in the lal dora] have become the provider for this housing, by building structures that are illegal. It’s not right, and it’s not safe, and it’s not healthy.”

Nisha Singh, like any reform-minded politician, is performing a balancing act. She needs to deal with the realities on the ground, like slum improvement and infrastructure upgrades. But she also sees the need to rewire the entire system, and to change the perception of government among voters. “Corruption and inefficient functioning are the bane of most government institutions in India, including MCG,” she writes in an email. “You will be surprised at how cynical and detached the citizens have become from governance and government institutions in India. Our constitution starts with the words ‘We the people of India,’ but we seem to have forgotten that the power and responsibility to revive our institutions lies with us, and that we only will have to demand and raise level of governance in India.”

Singh notes the role that social media played in organizing nationwide anti-corruption demonstrations last year. Gurgaon’s government, she says, should be leveraging open data and social media to harness the power of the city’s concerned citizenry. Already, the MCG has a website where people can report problems like piles of garbage, but that is just a beginning, she says. She is urging local officials in departments such as transportation to create more transparent and responsive agencies. In the traditional, paper-based and opaque culture of Indian bureaucracy, it’s a heavy job. But she keeps at it.

“Government departments are not giving out enough information, and people are forever distrusting them,” she says. “In cities, if you don’t have resources to solve problems, you should involve the people. There are enough brains in this city. I’m one of those people pushing for change.”

I spend 10 days in Gurgaon, and meet plenty of people who are working hard, doing what they can to make Gurgaon a better city in the face of rampant chaos, corruption and greed.

Vinita Singh, the woman who picked me up from the side of the road, described one of the poor women she works with as having himmat, a Hindi word that loosely translates as “guts.” Vinita has himmat herself. I saw it when we took the slum-dwellers to petition government officials for their benefits. I saw it when she maneuvered her little white car through brutal rush hour traffic. And I saw it when she was conducting a citizenship workshop with middle-class people at a comfortable café — work that she says in some ways is the hardest of all because, unlike the poor, the well-off can buy what the government does not provide and often don’t see the use of trying to work within the system.

I admired the himmat in Kiran Chaturvedi, who worked for more than two years to get her 700-unit housing complex to start composting instead of sending food waste to be dumped in a landfill. She overcame initial skepticism with hours of educational efforts and door-to-door work. Now a tidy, state-of-the-art composting facility occupies a previously unused building on the grounds of the complex, and hundreds of pounds of food waste are being put to good use. Kiran proudly shows off the bins of completed compost, poking at them and urging me to smell them.

The complex’s workers are as important to the program as its residents. “They perform it to the T,” Kiran says. The finished product is spread on the extensive landscaped grounds around the apartment towers. It is a small victory, but emblematic of the type of actions taken by individuals and housing associations around the city to fill the government void.

Kiran and I travel together to a local park, one of the very few public open spaces in Gurgaon, to see another composting effort she has helped to organize. In a spot where all sorts of garbage was once piled indiscriminately, neat pens of corrugated tin now enclose composting leaves and garden waste. Kiran tends to them as if they were in her own backyard, adjusting a protruding wire so that it won’t snag a passerby, sifting through the rich dirt and exclaiming over its restorative properties for the nearby rose beds. Now HUDA, the state development authority, is floating plans to improve the park further with new landscaping and lighting.

I met Kiran through Richa Dubey, another woman with himmat who has organized actions such as Gurgaon Girlcott, a one-day “stop shopping” event that protested violence against women.

I also met Mukta Naik, an architect and planner who has been helping slum-dwellers recover from a fire that leveled their crowded shantytown. In older slums, such as the infamous Dharavi of Mumbai, families have lived for years, building a city within a city, with its own social networks and infrastructural solutions. The jhuggis of Gurgaon are more ephemeral, hurriedly constructed on land that has yet to be developed and that will soon serve as the foundation of another office tower or luxury condo complex. Sometimes you see two or three shanties sandwiched between an office building and a mall, just steps from the parking areas where luxury cars await their owners’ return.

But as makeshift and uncertain as the jhuggis are, you still have to pay to live in them. In Gurgaon, all real estate has a price. The landowner sets up an agreement with a member of the migrant labor community who becomes, in effect, a contractor, collecting rent from the people who live there and who work at building and polishing the economic engine that is Gurgaon. A place in the cheapest one of these unauthorized slums costs about 700-800 rupees a month, Mukta tells me, or between $14 and $16. That’s a lot of money when food costs are rising and you’re making less than $4 per day, as the lowest laborers do.

Many of these workers are from far-away parts of India, such West Bengal. They have no connection to Gurgaon and don’t plan to settle. They speak their own languages and many of them — at least the older adults — plan to return home, having gleaned their small share of the piles of cash now being farmed in these fields. Mukta tells me that these people, for the purposes of the government, essentially do not exist.

And yet here they are, building a dream city, transforming Gurgaon into the place promised to the middle and upper classes in the glossy advertisements that line the roadsides and fill the newspapers.

These slum-dwellers are working people, and that is why no one was at home in the jhuggi we are looking for when it burned to the ground several months back. Parents were laboring and children were playing nearby when the blaze leveled the place.

As we jolt along in her black SUV, the roads growing narrower and the pavement vanishing, Mukta points out a partly constructed building that will serve as future home to the local mosque. She and a friend worked with this mosque to help the jhuggi-dwellers. The friend’s teenage children did a family-by-family survey to find out what the people needed most, and then gathered the goods together. Sandals and cooking utensils topped the list. “They lost everything in the fire,” Mukta tells me. “People were showing us burnt banknotes.”

We leave what semblance of a road we have been on and turn onto a dirt path that heads out into the fields. Eventually, we come to a stop in the middle of a field. About a dozen people emerge from a few brick huts as we emerge from the SUV – mostly kids and women, with a couple of young men. With the help of her driver, Mukta questions them.

Most of the people who lived in the burned-out jhuggi are gone, she discovers. These few who remain will be moving along before too much longer. The proprietor of a little tea shop that still stands on the site — a relatively sturdy structure of corrugated tin, selling a few basic goods — tells Mukta that they won’t be coming back.

Before we get back into the SUV, Mukta looks back at the mostly abandoned settlement. In the distance, the crane-topped skeletons of high-rises under construction fade into the darkening sky.

“Who ever thought Gurgaon would ever happen?” she says, surveying the incongruous scene. “We should have had a more inclusive vision.”

Many of the jhuggis, or slums, in Gurgaon are hurriedly constructed on land that will soon serve as the foundation for another office tower or condominium.

As filled with inequity and division as Gurgaon is, perhaps that vision is emerging. So many of the people I met in the city — Anupam and Saurav, Nisha and Mukta — told me Gurgaon was “unsustainable” as it is today. But each one of them, in his or her way, is working to make it more sustainable. And each small action undertaken by individual citizens is building a stronger civic foundation.

That incremental process is being helped along by steady and growing calls for reform, such as the Anna Hazare movement, and buttressed by new legislation like the Right to Information Act of 2005, which guarantees citizens the right to obtain information from the government within 30 days, and requires government agencies to computerize their databases in order to comply.

It is an incremental process, but Nisha Singh, for one, sees reason to hope that the gigantic, shambling creature that is Gurgaon can be brought into line. “If you don’t have ethical people running things, it’s not going to happen,” she says.

There is a new generation of leaders, she says, that is not content to continue with the corrupt and crippled politics they inherited.

“I am very optimistic about our ability to change the political system in India,” the councilwoman writes in an email. ”There is a wide consensus among the various reformists and civil society groups that the highest-impact reforms are the political and governance reforms. Winds of political reforms are blowing in India and will be the root for all other reforms that are required to take Indians to further growth and prosperity.”

Her email closes on a kind of promise. “Ten years from now, you will see better implementation, she says. “It’s the start of a revolution”

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Sarah Goodyear has written about cities for a variety of publications, including CityLab, Grist and Streetsblog. She lives in Brooklyn.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine