Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberIn a small classroom on the southeastern edge of Memphis, 20 fifth-graders in khakis and polo shirts work in small groups on a geometry lesson. The room is strikingly quiet when the teacher, Martha Mason, calls the class to sit in a semicircle before a large digital whiteboard. “Let’s shake and bake!” Mason says, challenging them to make the transition in a minute.

At the whiteboard, the group slowly works through calculating the surface area of a rectangular prism: Height x width x 2 + width x length x 2 + length x height x 2. Remember?

The students do remember, in a large part because the previous week they made Rice Krispie treats as a practical lesson in calculating surface areas — and then eating them. Mason holds up a cereal box and reminds them of how they worked through each side. She asks a student to try working the steps through at the whiteboard, and the other students walk the girl through it.

“Hands up if you have the answer.”

Hands shoot up.

Mason makes the tough job of captivating a room of 10-year-olds look easy. Winridge Elementary School’s principal, the upbeat Linda Campbell, chose Mason to represent the city’s teachers in a sweeping new initiative to improve teacher effectiveness precisely because Mason exemplifies a teacher in command of both content and the classroom. As a result, the face of the 34-year-old longtime Memphis resident has been splashed across a local billboard, a poster inside Winridge, countless brochures and a web site funded by the Gates Foundation. If the attention seems out of proportion, it’s because all of Memphis — as well as an influential coterie of philanthropists — is counting on Mason and 6,600 teachers like her.

Consider these statistics: In Memphis, where 83 percent of the city’s 105,000 schoolchildren are low-income and qualify for subsidized meals and 85 percent are black, only about 70 percent of students graduate from high school on time and average student scores on state tests hover in the 30th percentile. Memphis also has the highest poverty rate of any large metropolitan area in the United States, at 19.1 percent; in the metro region’s urban core, that rate soars to 26.5 percent.

In an attempt to resolve both these issues — low educational achievement and an unending cycle of poverty — Memphis is undergoing a substantive change to its education system. The hope is that improving the city schools will have a host of ramifications for the livability and viability of Memphis overall, from stopping the flow of families into the suburbs to developing human capital that might diversify and build the city’s economy.

Many American cities want to revamp their schools. But Memphis stands out because of the multiple strong forces of reform aligning at once. In 2008, a savvy school board and strong superintendent arrived, leading to more outside money — upwards of $100 million over several years — flowing to the district. The money all depends on the promise of the latest vision of progressive change to hit school systems around the country: teacher reform.

“But how realistic is it to hope to improve cities, from Detroit to Fresno, by improving teachers through better teacher evaluation.”

As long as there has been government funding of American schools, state and federal governments have been trying to fix them. The current wave of teacher evaluation is just the latest idea in a series of well-intentioned attempts to improve school districts, from the development of standardized curricula in the late 19th century, to the introduction of the corporate structure of school governance in the 1910s, to the innovation of IQ and other classificatory testing in the 1920s and, more recently, federal mandates for student achievement via former President George W. Bush’s controversial No Child Left Behind Act.

“There’s no question that this is a watershed moment for the specific area of teacher evaluation,” says Michael Grady, deputy director of Brown University’s Annenberg Institute for School Reform.

The question remains, however, whether a focus on teacher skills will in fact create better teachers, who can in turn transform students into productive learners and, finally, whether these newly minted critical thinkers will be able to, by virtue of their enhanced prospects, transform the ailing communities wherein failing schools are often located.

But how realistic is it to hope to improve cities, from Detroit to Fresno, by improving teachers through better teacher evaluation? One of the founding philosophers of our public school system, Horace Mann, wrote in 1848, “Education, then, beyond all other devices of human origin, is the great equalizer of the conditions of men … It does better than to disarm the poor of their hostility to the rich; it prevents being poor.”

Today’s logic extends that thought to consider the main influence on students in schools: the teacher.

“Highly effective teachers might add 1.5 years of growth, while the least effective would actually subtract a half-year of learning.”

In 2005, economics professor Eric Hanushek, a fellow at the conservative Hoover Institution at Stanford University, published a study arguing that teacher quality had a dramatic effect on student performance, and even more controversially, that teacher quality was not correlated with advanced degrees or time on the job. Hanushek, working with two other researchers, Steven Rivkin and John Kain, used economics modeling to determine the impact of a year with a particular teacher on a student. Highly effective teachers might add 1.5 years of growth, while the least effective would actually subtract a half-year of learning, he and his researchers found. This extra learning is the “value-added” impact of a teacher, based on a formula that compares the scores on a test her students took this year to the scores the formula predicted them to have received based on their demographic characteristics.

Deploying the study’s detailed statistics and charts, Hanushek helped promote the standard maxim of the high-stakes teacher-evaluation advocates: That the single most important school-based factor in a child’s success is the quality of his or her teacher.

After years of stagnating test scores and growing backlash against Bush’s complicated No Child Left Behind policies, the clarity of Hanushek’s message won it attention. Within five years, the idea had traveled beyond academia and into the policy handbooks of deep-pocketed school reform advocates such as the Gates Foundation, the Broad Foundation and New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

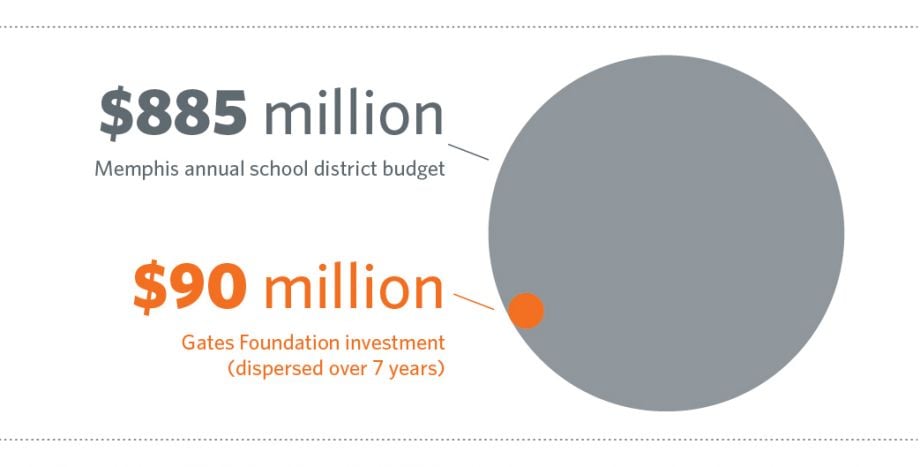

Yet the now-trendy idea had already taken hold in Tennessee. In 1992, the state became the first to use such analyses, based on the formula developed by another value-added pioneer, William Sanders. In 2009, the Gates Foundation committed $90 million, spread out over seven years, to Memphis to help the city develop its own system of teacher evaluation. (The Memphis grant was one of four public school districts to receive money from Gates to implement teacher evaluation programs.) Given all the investment into Memphis teachers, it made sense that the state would become the nation’s most high-stakes proving ground for the idea come 2010. By the start of the next school year, the value-added scores could decide whether a River City teacher should keep her job or be fired.

The current emphasis on improving teachers to improve schools is in contrast to the Bush-era effort, which focused mainly on student and school test scores. No Child Left Behind, passed in 2001, required every student be 100 percent proficient on state tests — as if every district were Lake Wobegon, where all the children are above average. Schools also had to make annual yearly progress (AYP), which meant that each year children in a grade had to do better than last year’s class. Stakes were high: If a school failed to make AYP for five years, it could be closed. Both AYP and 100 percent proficiency have proved to be so impractical that the Obama administration has allowed states to apply for waivers from No Child Left Behind; 10 states won waivers in February, among them Tennessee.

The Obama administration designed the Race to the Top Fund to be a less punitive approach to school reform. Instead of endless sticks, carrots — $4 billion worth of grants were handed out in 2010 — go to school districts who voluntarily change systems in ways that the administration believes will lead to higher test scores, including changing their teacher evaluation systems to include growth in student achievement as a measurement of teacher effectiveness, and to use these evaluations in hiring and firing decisions. In 2010, Tennessee was the first state to win a Race to the Top grant, in part based on the work Memphis and the state had already done to develop systems to evaluate teachers. In February, Obama proposed adding to his budget an additional $5 billion in competitive grants to states, following the Race to the Top model, focused solely on teacher improvement.

“You have these converging forces — the focus from the Feds, through Race to the Top, private funders such as Gates and Broad — placing emphasis and investing deeply in the methodology of evaluation,” says Grady, from the Annenberg Institute for School Reform. “Within the states, there’s a certain interest among commissioners and governors.”

The annual, taxpayer-funded budget for Memphis City Schools in 2011-2012 is about $885 million, roughly one-fifth of the total federal Race to the Top money. And while the Gates grant is huge, $90 million spread over seven years is dwarfed by the annual operating costs of a big school district such as Memphis. Still, the Gates money and the Race to the Top money drive policy on the ground.

“Some critics of the Gates Foundation and deep-pocketed reform advocates such as Bloomberg see a misguided, corporate agenda (sometimes morphing into right-wing union-busting and wholesale privatization of government services) behind the embrace of teacher evaluation.”

In an era of shrinking tax bases and cash-strapped local governments, there is no doubt in anyone’s mind that grants, whether from Washington or foundations, will play an increasingly critical role in public education. Still subject to debate, however, is whether or not this is a good thing. Some critics of the Gates Foundation and deep-pocketed reform advocates such as Bloomberg see a misguided, corporate agenda (sometimes morphing into right-wing union-busting and wholesale privatization of government services) behind the embrace of teacher evaluation.

“A lot of people who see Gates as a mainstream liberal who has tried to form dialog with the American Federation of Teachers,” says Stan Karp, an editor at the magazine Rethinking Schools. “But they have given funding to ALEC — which has a hard right privatization agenda. There’s a real overlap between mainstream corporate agenda and aggressive hard right.”

In last winter’s Dissent magazine, writer Joanne Barkan argued at length that big foundation support of education reform amounts to a struggle for private influence over public policy. Karp also notes that when private funders and hedge-fund donors discuss the $600 billion annual education market, it is explicitly as a “good business opportunity.” Adding to the confusion that surrounds a data-centric approach to evaluating teachers is the fact that only economists understand these formulae, and the computer software that runs them is often proprietary and sold on a state-by-state basis, making it hard for public agencies to explain the data points that are guiding decisions, and easy for critics to find business motivations among boosters.

Not all critics take specific issue with the merger of business and private industry with public education. Some simply say that reforming the way we train and retain teachers is not enough. To them, the depth of poverty and unequal distribution of wealth in the United States will simply beat out any earnest efforts at school-based change.

“The elephant in the room is that the real education challenge is not the kids with stable families,” says Marcus Pohlmann, a professor of political science at Rhodes College and the author of Opportunity Lost: Race and Poverty in the Memphis City Schools. “The problem is the kids with unstable families. I don’t see that putting great teachers in the classroom for six hours a day is going to make that much difference.” The mobility issue, where families or children move several times in a school year, he says, is likely a “derivative of poverty,” and one he is now studying.

Or to put it even more simply, Diane Ravitch told Jon Stewart, in March 2011, on no less a public forum than The Daily Show: “Wherever you find poverty and racial isolation, you will find low test scores — kids are hungry, homeless, sick, not getting any medicine — those things matter.”

(The Gates Foundation too acknowledges that there are factors beyond a teacher’s control that play into a student’s success. “We believe dynamic individuals selected well and with great leaders can make a huge difference in the lives of kids,” says Josh Edelman, the Gates Foundation’s program officer in Memphis. “By no means do we think that’s the determinant. But we think that a great teacher can make a difference working with the family and outside circumstances.”)

Yet despite the differing opinions on the motivations or approaches of these outside philanthropists, no one disagrees about their power to reshape America’s classrooms.

“The Gates, Walton, and Broad foundations came to exercise vast influence over American education because of their strategic investments in school reform,” writes Ravitch in her 2010 critique of the latest wave of school reform, The Death and Life of the Great American School System. “As their policy goals converged in the first decade of the twenty-first century, these foundations set the policy agenda not only for school districts, but also for states and even the U.S. Department of Education.”

Kriner Cash arrived in Memphis in 2008 from Miami-Dade County, where he had been chief of accountability in the nation’s fourth-largest school district. His hiring by the school board came after a yearlong search precipitated by the departure of the previous superintendent for Boston. When interviewing with the Memphis school district, Cash was called a would-be Memphis celebrity by the local alt-weekly, the Memphis Flyer, which wrote, “He is telegenic, with an intriguing, Obama-like biography” — referring to his biracial heritage and educational pedigree, with degrees from Princeton, Stanford and U Mass. With a resonant, slightly southern lilt to his voice, presumably from his years growing up in Cincinnati, and easy references to a bevy of educational statistics, Cash brought much-needed charisma and experience to the project of reinventing Memphis’ schools.

Cash spent four months taking stock of his new district. He identified eight “fault lines” in his kindergarten through 12th-grade students. These fissures were based on striking and stark data, among them a lack of pre-literacy skills in half of incoming kindergarteners; high retention (or “holding back”) rates leading to a third of all students being overage for their grade; high mobility, with an average of 50 percent of students changing schools at some point during the year; low college-readiness revealed by just 6 percent of the 3-4 percent of students taking the ACT receiving a “passing” score; and a graduation rate of just 66 percent. Finally, there was the issue of teacher training, effectiveness and retention.

“Within the first three years of teaching, I would lose 40 percent of my teachers,” says Cash of the numbers he confronted. “We didn’t know why, we didn’t have exit data. I said we have to look at our whole teaching staff.”

Around that time, Cash got the invitation from the Gates Foundation to apply for a grant that could help him answer some of those questions and hopefully, as a result, create a more effective corps of teachers.

In 2009, one year after moving to Memphis, the foundation promised the $90 million that Cash would put toward a massive reboot of the district’s professional development system. While those funds were soon met with $20 million more in donations by local businesses, among them FedEx, AutoZone and International Paper, the Gates money, with its data-driven approach to improving teacher effectiveness, set up a new structure for reform.

At the core of the Gates program is a new Teacher Effectiveness Measure (TEM), implemented system-wide in September 2011 after a year of study funded by the Gates grant. The TEM uses five measures to judge if a teacher is contributing to student learning. Observations count for 40 percent and are conducted by an administrator, usually the principal, who has gone through a summer plus several sessions of training in how to measure teaching aptitude. The next most important items are student learning, based on the controversial value-added test scores (35 percent) and student learning based on state tests (15 percent). Student evaluations and teacher subject knowledge make up the rest of the pie. Using the TEM, a classroom observer can score a teacher between one and five, with five the highest, based on a detailed checklist that itself required extensive development.

Often these numbers give an accurate sense of a teacher’s skill level. Principal Campbell knew that Martha Mason was a great teacher based on Mason’s leadership in the school and orderly, productive classrooms. But TEM proved it numerically: Mason scored not only between four and five on her observations but also between four and five on the amount she increased her student’s learning, as judged by the test.

To evaluate the evaluation systems, Gates has also funded the four-year, $45 million Measures of Effective Teaching (MET) research project. The project recruited 3,000 teachers in six school systems around the country, including Memphis, to allow themselves to be observed and rated by many people, in many ways. The most recent findings demonstrate that the more measures — and more different kinds of measures — used to evaluate a teacher’s ability to improve her students’ learning made the entire effort more predictive. “One of the key things that we gleaned from MET,” says Josh Edelman of the Gates Foundation, “is that multiple measures matter and that the use of student surveys enhances the predictive power of the TEI.”

Memphis City Schools is just halfway into their seven-year, Gates-funded project and has spent just $20 million of the money. Since 2009, the school district recruited 500 teachers to choose the evaluation rubric that they liked best. The teachers ended up choosing the model that had been used in Washington, D.C. called Impact, and then modified it substantially for Memphis.

The final product, the Teacher Effectiveness Measure, a 17-page manual of four different teaching benchmarks and subsets of checklists, is what principals and other evaluators bring with them when they walk into a new teacher’s classroom for the six observation sessions done through the year. A teacher would rate highly effective on one of the 11 measures only if there was visible evidence that she had been able to communicate lesson objectives in language the kids could understand, describe clearly what mastery of the objectives looked like, allowed the students to connect with prior knowledge and allowed the students to explain their answers themselves “authentically.” Mason, for instance, made the goal of the day clear — calculating the area of a prism — made sure the kids knew it, kept referring to the Rice Krispie Treats and asked the kids to explain their reasoning each step of the way. Still, if the kids on that particular day couldn’t get the lesson, she herself might be rated lower.

The second prong of the four-part TEI strategy was to hire and retain teachers more effectively. In Memphis, as well as in other districts grappling with that goal, much of the work is being outsourced to another Gates-funded initiative, The New Teacher Project. Cash and his deputies are just engaging with the most expensive part of the strategy: Changing teacher compensation, which accounts for 80-85 percent of the total schools budget and will take up a similar amount of the Gates grant, say Cash and Edelman.

“On the thorny issue of compensation, which takes up so much of the budget, Cash is blunt: ‘You can’t do it on the cheap,’ he says. ‘You are not building widgets.’”

Cash himself looks slightly exhausted by the minutia of the momentous changes he’s shepherding. Despite the momentum of his teacher effectiveness programming, he’s had a rough year. The entire city watched sympathetically as his wife of three decades battled cancer and then passed away last year. More recently, his closest deputy, Irving Hamer, resigned after harassment allegations. In addition, Memphis city schools face another massive logistical hurdle, as the city schools plan to officially merge with the suburban county district in a year, radically reshaping the region’s bureaucracy, and potentially, its classrooms. It is a union that could cost Cash his job, since the combined district will need a new superintendent.

On a recent spring day, he rushed in from a meeting with the editorial board of the local paper, the Commercial-Appeal. He looked distracted by pro-forma questions about the structure of TEI. But as he began to discuss the challenges facing the children in his district — from lack of vision care to high mobility rates — he grew animated, rattling off what he had done to address these critical issues. A new bus contractor had been hired, getting the kids to school on time, which hadn’t been happening previously. Pre-kindergarten enrollment has doubled. A STEM (science, technology, engineering, math) virtual school had enrolled 75 students and was by all accounts beloved. After-school programs had expanded.

On the thorny issue of compensation, which takes up so much of the budget, Cash is blunt: “You can’t do it on the cheap,” he says. “You are not building widgets.” Memphis currently has one of the lowest per-pupil costs in the country, at $8,300 per child annually. “I’m not for wasteful spending, but once you make a commitment to make sure all kids are globally competitive, that means that’s going to cost something,” says Cash. That is particularly true, say many education experts, in cities and regions with concentrated poverty, where the families of the students don’t have the means to provide enrichment themselves.

When Marcus Pohlmann wanted to study impact of poverty independent of race on student achievement in Memphis schools, he sought to compare schools with student bodies of middle-income black children to those with poor black children. But he could not identify any majority black middle-income schools in Memphis, so he compared somewhat poor to deeply poor (86 percent free or reduced lunch with 97 percent). The very poor schools had some advantages, such as lower average class size and more experienced teachers. Yet across the board, from grades three to five, in math and English, from 1995-2002, the poorest children did many percentage points worse on state standardized tests than the merely poor children.

Many towering figures in education, including Diane Ravitch, Gary Orfield and Edward Fiske (editor of the Fiske Guides), have pointed out the link between poverty and poor educational outcomes. In a December 2011 op-ed for the New York Times, Fiske and professor Helen Ladd pointed out that on the 2009 Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) reading test, poor students did worse within every country. Ravitch has argued in the pages and blog of the New York Review of Books that poverty and social conditions “are the root causes of academic achievement.” She also reminds us that Americans have never done particularly well on the PISA and that education “crises” are often most noticed because of compelling political needs. In fact, the National Center for Education Statistics notes that math scores on national tests have actually been steadily improving among middle-school students.

Many programs have tried to zero in on this connection between poverty and achievement, through all-encompassing “cradle to career” initiatives that tackle barriers to learning from the prenatal environment to housing and environmental health. These include the Harlem’s Children Zone, Cincinnati’s Strive, a similar multi-city initiative funded by the Living Cities philanthropic collaborative, the federal Early Head Start program, and state initiatives such as investment in universal pre-kindergarten (one of which, in Washington, is partially funded by Gates). These programs usually do show limited success, either in keeping children in school longer or leading to better overall life outcomes. Unfortunately, they are also quite costly, which makes implementation a challenge.

Poverty and class have also become ways of talking about race without talking about it, since class and race are strongly aligned in the cities of this country. Overall, according to the most recent census data, just over 9 percent of white families live below 125 percent of the poverty line, while nearly 23 percent of both black and Hispanic families do (the overall rate in the U.S. is about 11 percent). At the same time black students have been scoring at least 20 points lower than whites on national standardized tests (on a 500-point scale), since 1978.

Few school officials, however, emphasize race anymore. Many school districts (including Memphis) were under court order to desegregate in the 1960s and ‘70s (and some of those orders held until as recently as a decade ago). Now districts that are concerned about achieving racial and economic parity in their schools use tools such as magnets or expanded metropolitan region boundaries.

One reason may be “the broader discussion of, are in we in a post-racial society, do we need race-conscious efforts,” says Genevieve Siegel-Hawley, professor of educational leadership at Virginia Commonwealth University, who has studied systems in Chattanooga, Tenn., and Louisville, Ky., among others, which took both approaches. “The other reason might be directly or indirectly dealing with Parents Involved” — the 2007 Supreme Court decision that held that districts cannot attempt to balance their schools racially — “and knowing that court isn’t favorably looking at race as sole criteria. So they are trying to craft these multi-pronged plans.”

The de-emphasizing of racial desegregation as a tool for equity and achievement may also come in part because the presumption that separate is inherently unequal has lessened, especially as more black politicians have come to power since the 1990s. In a broad reevaluation of the rationale behind Brown v Board of Education, from both the right and the left, from John Roberts to Lani Guinier, legal scholars are wondering if the idea that black children feel inferior if they are not in white schools is itself inherently demeaning. Arguments on the left go one step further, however, and say talking about race is still critical — but to examine structural forces reinforcing inequity rather than psychological ones.

Touting teacher evaluation as a way to improve schools means generally states, districts, funders and school employees can avoid conversations about race and class and focus instead on procedures and processes. But Cash says there’s no reason not to attack both procedural and social problems at once. In fact, he says, they are interdependent. “If you have high poverty and high economic segregation and low level of college attainment and you don’t do something about that, it’s a human capital issue, you are in a losing ballgame,” he says. “And that’s why the Teacher Evaluation Initiative is important part of growth of county as a whole — it produces stronger and more competent human capital.”

Since the Gates money started coming to Memphis in 2009, the district’s schools have raised their graduation rate to nearly 71 percent from 66 percent. That must still go up more than 4 percent by 2016 to meet the district’s pledge to Gates.

Another indicator of success: Now, all students take the ACT. Previously, just 3-4 percent of high school students chose to, and just 6 percent received “college-ready” scores of 19. That means, however, that the proportion of students who hit a “college-ready” score has slightly declined to around 4-5 percent.

Yet right now, the data is still out on whether the teacher evaluation has been a success by the numbers, in a large part because this is the first year of district-wide implementation. Gates’ Edelman praises Memphis as a whole, already, for integrating student perceptions into its teacher effectiveness measure for involving local philanthropists and businesses from the outset.

But most important, say Mason and other teachers, individual teachers, schools and indeed the entire district are taking hard looks at themselves. A principal, having undergone training in conducting observations under TEI, now must have a conversation with every new teacher six times a year, before and after each observation. (Experienced teachers do this four times a year.) In turn, principals with abrasive managerial styles might themselves get some collegial conversations from district administration.

Knowing what is expected in very concrete terms makes things easier, even if there’s more work. “This year versus last year, I am teaching the same concepts, but the difference is phenomenal,” says Mason. “I think it comes from being planned, prepared, looking at the indicators ahead of time.” The ebullient Principal Campbell also points to the intensive peer observation — teacher-to-teacher — and mentoring.

A handful of teachers even work the classroom with earbuds and unseen coaches whispering of-the-moment tips, thanks to another Gates pilot program run by former English teacher Monica Jordan. All teachers now have 360-degree cameras in their rooms, which they elect to turn on. If they choose, they can upload footage of themselves teaching to a centralized website and ask for tips, plan collaboratively or show off a particularly great lesson.

Even if she didn’t have the fancy gadgets at her fingertips, says Jordan, the important thing is “just a district sitting down and talking about what constitutes effective teaching. Those conversations are now not nebulous. We are able to get really clear — it says right here [on the TEM rubric] ‘you are going to engage the students in this manner.’”

Still, the state requirement that 50 percent of a teacher’s evaluation be based on student achievement strikes some outside observers as counterproductive. “The tests people use to establish the amount of student learning are not very good, they are seriously flawed,” says Charlotte Danielson, a leading education researcher whose own measure of teacher observation is being used by the Gates MET project. She continues: “Even if the tests are good it’s virtually impossible to attribute to individual teachers the learning of individual students. These numbers are very unstable.”

Similar critiques of the use of value-added in teacher evaluation come from Ravitch and other scholars such as Aaron Pallas, professor of sociology and education at Teachers College. He argued in the Washington Post that the attachment of a ranking or performance category to the value-added ratings is itself highly subjective and even arbitrary.

States and districts are barreling ahead anyway, and deploying value-added scores in more or less nuanced accounts of what’s happening inside our classrooms. In Memphis, at least, teachers helped develop the way 40 percent of their evaluation would be scored, through the TEM, and multiple other inputs, such as student views, are making up some part of the evaluation pie. In addition, district administrators are taking lessons from the past three years of study and using them to adapt.

Early in the year, when principals and teachers first started discussing their observations, they realized no one had given examples of what, say, using “strategies that challenge students to probe for higher-order understanding, synthesize complex materials, and arrive at new understanding” (one of the criteria for receiving a top score on the MET) actually looked like in a fifth-grade classroom. So they came up with examples and annotated an already small-type-filled document. “It was about empowering teachers as much as focusing on high expectations,” says Tequilla Banks, the coordinator for TEI in Memphis. “Has it been flawless? Absolutely not, But we’ve kept teachers involved in the design and the refinement.”

And what about school systems trying to refine themselves without the $90 million? Memphis and Gates officials hope that the model can be replicated at a low cost, since their work will stand as example and incentive. Using the Gates grant, Memphis has itself in turn given $5,000 seed grants to other regional systems. How the thorny, expensive issue of improved teacher compensation will unravel remains to be seen, however.

There’s one other big challenge facing Memphis City Schools. It is, perhaps not surprisingly, also about money and power. The Memphis schools get a large portion of their operating budget from the surrounding suburbs that comprise Shelby County, even though the two are currently separate school districts. Shelby County and MCS pool their education-related taxes and then divvy them up based on student population. (MCS has 106,000 students but has been losing students slowly for years, while Shelby County has around 48,000.) For years, this arrangement was more or less protected by a Democratic majority in the state assembly. But after the assembly swung Republican in 2008 and 2010, the Memphis School Board of Commissioners worried that law would be rewritten to allow the county to separate permanently from the city, leaving it in deeper financial distress. So in 2010, the Memphis Board of Commissioners voted to dissolve the city school’s charter, which had existed since 1869.

That meant that the county and city schools would become one in function as well as in finances. “It was purely an economic issue,” says Commissioner Tomeka Hart, who took issue with one report calling it a move toward integration. “The county could have created a district with a separate tax authority, and that would have meant less money for Memphis schools.”

Those in Memphis stress the opportunity that comes with consolidation. They have no other option. “It’s time to look at both systems and say both have some challenges,” says Hart. “Both educate kids who don’t need us very well but both don’t educate the kids that need us.”

In the end, the suburban county schools may need Memphis and its reform work as much as Memphis needs the suburban money. Banks, the TEI head, says that the county’s ACT college-readiness is only 20 percent. “That points to me the need to really focus on education in our entire community.”

No one knows yet what will stay and what will go in consolidation. Cash may lose his job, or not. The carefully focus-grouped and researched TEM may be scrapped for the state’s off-the-shelf TEAM evaluation metric. Edelman, of the Gates Foundation, says he will continue to work as a “facilitator figure” for both the county and the city, which must unite by August 2013. Consolidation, he says, “has created a lot of anxiety, but it’s a huge opportunity to think about how we use resources and people effectively, in both Memphis and Shelby.”

As much as local officials brush off the idea that this particular opportunity may involve desegregating by race and economics, recent academic research points to the potential salutatory effects of making school districts as wide as possible. “The consolidated district will diminish the segregating impact of school district boundary lines — powerful but invisible constructs that remain among the most fundamental barriers to equal educational opportunity today,” wrote Siegel-Hawley, the educational leadership professor, in an opinion paper on Memphis published last October in the Teachers College Record. Siegel-Hawley and colleagues such as Gary Orfield at UCLA have long looked at how the composition of schools reflects neighborhood compositions. Federal programs such as Title VI sought to desegregate schools economically and racially, in part by providing federally subsidized mixed-income housing.

But Siegel-Hawley’s provocative paper and recent research suggest that, instead, desegregated schools in regional metropolitan areas can in turn integrate housing and lives. “Black-white housing segregation fell twice as fast in Louisville, which had the most comprehensive school desegregation policy, as in Richmond (VA), which had the least,” she explains. Or, to put it another way, there’s no point, if you are a suburban family looking for less troubled schools, in moving away from a school system if you have to go incredibly far to get beyond similarly integrated schools. Siegel-Hawley’s recent research focuses on Chattanooga, where “residential racial isolation” declined substantially after an urban-suburban school system merger, coupled with the development of magnet schools within the new district. (Consolidation of regional school districts to integrate is perhaps particularly meaningful in the South, where blacks were expressly prohibited from learning to read until emancipation, where black schools were underfunded or unfunded until the 1960s, where court-ordered desegregation plans were flouted throughout the ‘70s and where relatively open space means those who can move often do.)

Schools can reflect and even magnify social problems, such as poverty and crime. But they are also among our most powerful national institutions. They are drivers of systemic change, not the passive objects of outside forces. Our schools accrete all kinds of capital — human, social, economic — and then spit it back out again in new forms. We pour millions or billions of dollars into districts all around the country. In turn, they employ us, they care for our children while we work elsewhere, they teach our children not only to perform higher-order math functions and write a five-paragraph essay, but how to understand and perform within an ordered system.

The Memphis schools are themselves being shaken up by not only the Teacher Evaluation Initiative but also by consolidation. As the Gates Foundation’s Measures of Effective Teaching itself stresses, multiple inputs tend to make for the most accurate and valuable assessments. In the same way, two accidentally colliding, hugely ambitious programs of school change, as crazy-making and difficult as they may be, may have a chance of budging the most intractable problems of racial and economic inequality.

“The real benefit to everyone is you get children going to school together, to classes together, in after-school together and traveling together,” says Cash, speaking about consolidation — although he might as well be talking about a well-marketed, fully functioning urban public school system. “I just met an eighth-grade girl — she’s already doing advanced calculus. She could be mixed with other kids who may not be doing as well. She is a Memphis student and could help a Shelby county student. These are adult boundaries, not children’s boundaries.”

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Carly Berwick writes about education and culture for Next City, as well as The New York Times, ARTnews, and other publications.

Tim Gough has been working in Philadelphia as a designer and art director for various agencies and design firms for the past eight years. His art is influenced by the screen printed process and mid-century graphics. In 2007, Tim left the agency life behind to pursue illustration and art full time. His work has been found in books, magazines, newspapers and other ephemera nationwide and abroad. Tim also publishes a limited-edition zine called ‘Cut and Paste,’ a collection of drawings and things. He frequently shows his drawings and screen prints in various galleries and shows.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine