Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

A heavy haze of pollution blankets Delhi during the morning rush in this November 2017 photo. In cities with a population greater than 14 million, Delhi ranks the worst for air quality.

AP Photo/Manish Swarup

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberThe cloud of toxic air that envelops much of northern India casts a grim shadow on the country’s economic growth story. Frustrated Indians and puzzled visitors wonder why an aspiring global superpower cannot control its record-breaking air pollution levels. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), India is home to all but one of the world’s 15 most polluted cities. So imagine the surprise when, in April, gas stations in the capital, Delhi — which has the dubious distinction of being the world’s most polluted megacity — quietly started selling ultra-low sulfur fuel that aligns Indian vehicular emissions with the highest standard legislated by the European Union.

All vehicles in Delhi now run on Bharat Stage-VI (BS-VI) fuel, which is equivalent to Euro-VI standards. How did India, notorious for failing to tackle its pollution problem, get on the fast track to using the cleanest available fuel? The answer lies in judicial activism, a uniquely Indian approach to curbing lethal air pollution. “In most countries, government agencies implement environmental plans. India is the most dramatic example of judges taking the initiative on pollution control, while there is apathy from the government,” says Jay Pendergrass, Vice President (Programs) and leader of India Program at the Washington D.C.-based Environmental Law Institute (ELI).

Starting in 1999, when India introduced the first-ever fuel specifications based on environmental considerations, the push for higher emission standards and the implementation on accelerated timelines have come from India’s Supreme Court. Over the years, public-interest litigation (PIL), or a lawsuit in the public interest, has been the primary tool for Indians seeking environmental protections. On PIL related to air pollution, the Supreme Court has famously observed that health of people is “far, far more important than commercial interests” of car manufacturers.

India’s transition to the cleanest available fuel for vehicles is remarkable for many reasons: Delhi has leapfrogged from BS-IV to BS-VI grade fuel, skipping the BS-V stage, at a negligible cost to Delhi’s 10 million-plus car owners. Following a smooth rollout of the BS-VI fuel supply across Delhi’s gas stations, the Supreme Court has asked the government to roll out the clean-burning fuel not only across Delhi’s sprawling suburbs (called the National Capital Region) but also in 13 additional metro areas as early as next year. The rest of India will shift to BS-VI norms for new vehicles in 2020, four years ahead of the schedule set by the Road Transport Ministry. Had India followed that roadmap, BS-VI norms would not be implemented until 2024.

Will shifting to Euro-VI emission standards mark a measurable turning point for India? What’s next in Indians’ fight for clean air, which many frustrated citizens worry is a losing battle, despite steadfast judicial support for their cause?

The accelerated BS-VI rollout reflects an urgent health crisis. India’s toxic air quality was quantified in May, when the WHO ranked air pollution in more than 4,000 cities across more than 100 countries. The report compared average amounts of PM2.5, or particulate matter less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter. PM2.5 are very fine particles that penetrate the lungs, triggering or worsening chronic diseases such as asthma and coronary heart disease. The world’s most polluted city, Kanpur in India, has an average PM2.5 level of 173 micrograms per cubic meter (µg/m³), compared to the WHO’s recommendation of no more than 10 µg/m³. Delhi averages PM2.5 levels of 143 µg/m³, while the cities of Faridabad, Varanasi, Gaya and Patna fall somewhere in between Delhi and Kanpur. All of these cities are in north India, which bears the brunt of India’s gigantic air pollution problem.

Students in Delhi wear masks to protect their lungs during a November 2017 protest over the dangerously high levels of air pollution in the city, which caused school closures as well as disruptions to flight schedules and cricket matches. (AP Photo/Manish Swarup)

Skeptics question whether adopting Euro-VI standards that have produced results elsewhere will be sufficient to reduce the toxicity of the brew Indians inhale on a daily basis. To understand how vehicular emissions contribute to north India’s deteriorating air quality, look to a 2016 study conducted by two Indian Institute of Technology (Kanpur) professors for the government of Delhi. The study identified the top four contributors of PM2.5 emissions in Delhi as: road dust (38 percent), vehicles (20 percent), domestic fuel burning (12 percent) and industrial point sources (11 percent).

You’d think air pollution would be India’s destiny, given that it’s a dusty country. Polash Mukerjee, research associate at India’s leading environmental organization, the Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), disagrees. “India is a dusty country by nature. But road dust is not toxic by itself,” he says. “What makes it toxic is when dust is mixed with vehicular pollution and circulated and re-circulated. People’s exposure to this toxicity is very high when you consider the number of people who live by busy roads in urban India.”

According to Mukerjee, vehicular emissions are the single largest source of both toxicity and exposure to air pollutants in India. In 2015, of the 6.5 million people killed by air pollution worldwide, the largest number — 1.8 million — lived in India. Diseases attributed to air pollution are now the second leading cause of death in the country, after child and maternal malnutrition, accounting for nearly 10% of all premature deaths. India’s present and future hang in the balance; one in every three children in Delhi, for example, suffers from impaired lungs. But North Indians hardly need these statistics to grasp the scale of the problem. Their day-to-day lives are marred by emergency visits to hospitals, school closures, disrupted flights, and delayed cricket matches.

The shift to higher emission standards hasn’t come a moment too soon. India’s domestic car market is now the world’s fourth-largest behind only China, USA and Germany. Automobile sales grew by 9.5 percent last year, adding more than four million vehicles to Indian roads.

The gains from transitioning to BS VI-grade fuel can be huge: 70 to 90 percent less particulate matter and nitrogen oxide per kilometer, according to various estimates. BS-VI is regarded as the cleanest fuel because its sulfur content is 10 parts per million (ppm) compared to 50 ppm in BS-IV. Less sulfur supports the use of more advanced after-treatment devices (an umbrella term for the filtering technology that reduces harmful exhaust emissions).

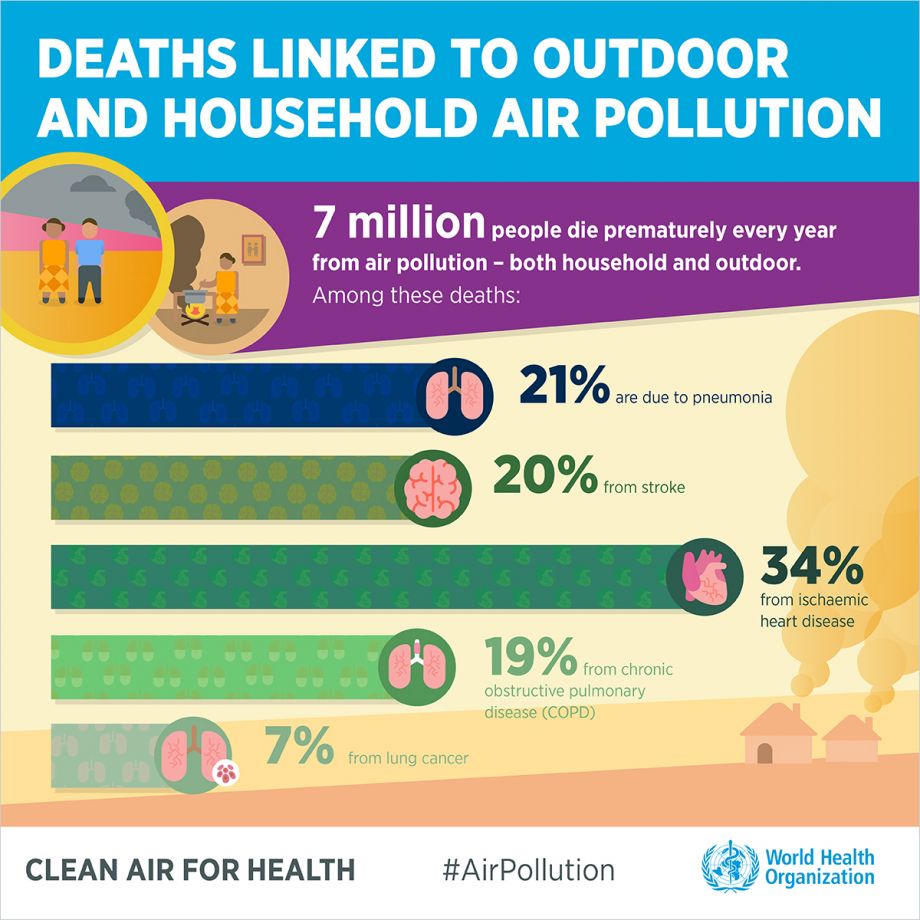

Credit: World Health Organization

Experts see BS-VI as a gift that will keep giving. “The health benefits of BS-VI will offset the increase in costs for the industry within the first few years of the program,’ says Debasish Bera, a director in the Oil & Gas practice of PwC India, noting that the early transition to BS-VI will have significant long-term impact: “Due to the long lifetime of heavy-duty vehicles, the early adoption of BS-VI standards will continue to generate emission reductions and reduction in premature mortality rates by 2030.”

Moreover, for the first time in India, auto emissions will be tracked and measured; In Euro-VI compliant cars, real-time driving emissions are monitored throughout the lifecycle of the vehicles. You have to only consider the Volkswagen scandal in the US to know why that’s important; the carmaker was found to be cheating emission tests and concealing the true amounts of pollutants in its exhaust. This real-time emissions monitoring represents a huge improvement over India’s current system of issuing “pollution under control” certificates, which are widely regarded as a sham formality.

However, Delhi can’t breathe easy just yet. While BS-VI fuel has come to India’s capital, BS-VI compliant cars are still a rare luxury in this country. Currently, only high-end automakers such as Mercedes-Benz and BMW sell these cars in India. Not until after April 1, 2020 will the volume players in India’s price-sensitive car market, such as Maruti Suzuki and Hyundai, be required to manufacture and market BS-VI vehicles. Until then, Delhi-ites will run their BS-IV cars on the BS-VI fuel. The vehicles that currently crowd India’s roads don’t have advanced technology such as diesel particulate filters and urea injection; because of this, they won’t see the full benefit from the new low-sulfur fuel.

India’s auto industry is switching gears, grudgingly. The Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers (SIAM) has a pending request before the Supreme Court, asking for not just two more years before selling BS-VI cars, but also an additional 3 month-window after March 31, 2020 to dispose of their existing BS-IV stocks.

What holds back the Indian auto industry from selling cleaner cars is not a problem of technology, but of scale and cost. Technology, in fact, appears to be the least of India’s problems when it comes to cleaning up its act. The country has rapidly increased its renewables capacity to generate clean electricity. By some estimates, it may even achieve 40 percent non-fossil fuel-based power capacity as early as 2020 — ten years earlier than India’s Paris Agreement targets.

Automakers have kept up with rigorous standards, but only for global markets. Maruti-Suzuki, for example, exports to Japan and Europe the made-in-India Baleno hatchback, which adheres to the highest emission standards in those markets. So the industry is familiar with BS-VI technology. The challenge appears to be one of scale, ramping up capacities and aligning suppliers to manufacture BS-VI compliant vehicles for the vast domestic market.

SIAM says the auto industry must invest more than $15 billion to meet the new regulatory standards, in particular to adapt Euro-VI technology to Indian driving conditions. That’s an expensive undertaking, particularly for an industry that in 2017 had to liquidate stocks worth $3.1 billion, based on an earlier Supreme Court directive. Similar to how it accelerated India’s transition to BS-VI technology now, India’s apex court in 2017 pushed for BS-IV compliant vehicles by ordering the auto industry to stop selling BS-III vehicles.

Time and again, the Indian Supreme Court has issued orders that have burnished its credentials as the environmental steward of India. Where successive Indian governments have faltered, the judiciary has stepped in. “What the Indian courts are doing fits their context. The judiciary’s role is needed and appropriate in India,” believes ELI’s Pendergrass. There is a strong constitutional basis in India for judicial activism on the environment. The right to life is fundamental, per Article 21 of the Indian Constitution, and Indian courts view a clean environment and public health as integral to Indians’ right to life. Pendergrass contrasts that with the U.S., where successful environmental legislation relies on the Commerce Clause in the American Constitution.

These identical perspectives show the visual difference in Delhi's air quality from one year to the next. In the top photo, traffic passes the India Gate landmark in October 2016. The bottom photo is the same view from October 2017, with smog so thick the monument is barely visible. (Top: AP Photo/Altaf Qadri; Bottom: AP Photo/Tsering Topgyal)

In India, judicial activism on environmental issues is not just the domain of the Supreme Court. In 2010, India established dedicated green courts in the form of the National Green Tribunal (NGT) to rapidly resolve environmental cases — a move that acknowledges both its raging environmental conflicts and the slow-moving judicial system. The tribunal’s first leader, Justice Swatanter Kumar, acquired a formidable reputation for being a defender of the environment.

But environmentalists worry about the future of India’s green courts. Since 2014, the NGT has been a thorn in the side of the big business-friendly, right-wing government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Environment ministers in the Modi administration have complained about the “extreme” and “overreactive” positions of the NGT. And leading environmental lawyers accuse the government of hollowing out the NGT, leaving it unstaffed and making its appointees subservient to the ministry of environment.

The long-term effectiveness of the Indian judiciary in upholding environmental rights remains in question. Judges typically don’t have the technical knowledge to decide on complex, multi-dimensional, scientific, health and environmental issues facing Indian communities. Moreover, courts can order, but only governments can enforce. “In India, there is so much reliance on public interest litigation, but very little happens by way of enforcement,” says Pendergrass.

Similar concerns surround the federal government’s new National Clean Air Programme, which puts the lion’s share of enforcement responsibility on individual state governments. Air pollution in north India is a regional issue that requires close federal-state coordination among different political parties. In India’s current fractious domestic political environment, to assume that level of cooperation is laughable.

When it comes to enforcement, the Supreme Court also has been known to step in. Certainly, that’s true of the court’s approach to air pollution — so much so that almost two decades ago, with the court’s help, Delhi came close to fixing its pollution problem.

To know what lies ahead for India, it’s important to examine how emission standards have evolved in the country.

In 1998, public interest litigations demanded cleaner air in Delhi. In response, the Supreme Court ordered the establishment of the Environment Pollution (Prevention and Control) Authority (EPCA), which continues to serve as a fact-finding body for the court. Back then, the EPCA worked with the Delhi government to recommend that the capital shift its entire bus fleet to Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) fuel, a cleaner-burning fuel compared to petrol and diesel. With that, the unthinkable happened; Delhi began running the world’s cleanest public bus system in the early 2000s.

Various independent and Indian government studies have established that converting commercial vehicles to CNG significantly improved Delhi’s air quality, which in turn, measurably reduced the risk of illnesses and premature deaths. Today, CNG is available in more than 50 Indian cities.

If EPCA recommended the CNG plan for Delhi, it was the Supreme Court that mandated the plan. In India, as in many places around the world, best-laid plans can falter as governments retreat and bureaucracies delay. Delhi managed to avoid such backtracking because the court set deadlines for first buses, and then for taxis and three-wheeled auto-rickshaws to switch to CNG. In addition, the court directed state-owned oil companies to establish more fueling stations to ensure an uninterrupted supply of the fuel.

Delhi’s choked citizens scored a key victory. But these gains from public transit switching to CNG were subsequently negated as privately owned diesel cars flooded Indian roads.

Many hold the automobile industry responsible. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the Indian car market took off. Car companies were eager to sell low-cost diesel vehicles to first-time car buyers and as private taxis. “We wanted buses to move to the cleaner CNG. We certainly did not want cars to use the dirty, toxic diesel!” writes leading Indian environmentalist Sunita Narain in her book, “Conflicts of Interest.”

The automobile industry, represented by ace lawyers — including none other than India’s present finance minister, Arun Jaitley, and past finance minister, P Chidambaram — succeeded in preventing a ban on diesel cars.

This literal dark cloud that hovered over India had a silver lining. “The Supreme Court, faced with this barrage of opposition from the industry… decided that instead of banning diesel in private cars, it would push for drastic improvement in fuel and emission standards,” writes Narain. And thus, in April 1999, the first-ever standards for emission-control technology and fuel were introduced in India, by the order of the Supreme Court.

More than any other contemporary milestone, BS-VI fuel represents a paradigm shift for India. The technology will not only help to clean India’s air, but it will also force modernization of the car market in important ways. Finally, the days of the dirty diesel car may be numbered in India. Euro-VI compliant diesel cars are more complicated and more costly to manufacture. Analysts expect diesel cars to become more expensive and fall out of favor with the Indian consumer. Further, India’s leap to BS-VI fuel means that something has to be done about its legacy fleet. It’s nearly impossible to envision the logistics of eliminating from India’s roads the vast number of privately owned, low-cost and emissions-belching diesel vehicles. But the government has proposed India’s first-ever scrap policy for commercial vehicles, a welcome step in a country where the ultimate fate of used cars remains unknown.

Even the reluctant auto industry knows that putting in place a modern eco-system of car production in India’s relatively low-cost labor environment would eventually make it more competitive in the global market. The country’s oil industry has been quicker to embrace change. “There has been a strategic push for refining capacity expansion from the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas of India. With BS-VI, in the next two years there will many technological advances from which India will benefit for years,” believes PwC’s Bera.

After the rice harvest, farmers in Punjab burn the remaining vegetation to quickly clear the fields so they can plant the next crop. Burning of crops in surrounding rural areas is a significant source of particulate matter air pollution for north Indian cities. (Photo by Neil Palmer/CIAT)

Indeed, India’s state-owned as well as private refiners are pursuing ambitious expansion plans, which reflect geopolitical concerns about energy security and economic concerns about crude-oil price volatility. Despite importing more than 80 percent of the oil it consumes, India is a net exporter of refined petroleum product. The shift to Euro VI-grade fuel, estimated to cost India’s oil industry US$4.5 billion, could help secure fuel supplies at home as well as boost exports to developed countries.

These benefits are real, but not immediately obvious to the average citizen. Indians, ever cynical about their country’s environmental degradation, won’t breathe noticeably cleaner air until BS-VI compliant cars have hit the fast lane in India, after two or more years.

Frustratingly, some factors responsible for north India’s air quality are beyond human control. Geography is one of them. Winds from throughout India and neighboring countries converge and stagnate in the landlocked Indo-Gangetic plains (encompassing northern India, eastern Pakistan and all of Bangladesh), situated on the foothills of the gigantic Himalayas. North India’s cooler winter air makes this bad situation worse by trapping pollutants and creating a choking blanket of smog. Last winter, PM2.5 levels in Delhi soared as high as 500 µg/m³ on certain days. In contrast, the bustling cities of southern coastal India, including Mumbai, Chennai and Bangalore, benefit from sea breezes that can flush out polluted city air.

In this topographic punchbowl, some additional, uniquely South Asian sources compound the air pollution, from villagers burning wood and cow dung for cooking to farmers burning crop to clear out pests and create fertilizing ash. In theory, substitute technologies such as seeders in farms are available and can make a huge difference. In practice, distressed, debt-ridden Indian farmers who themselves suffer the ill effects of smoke remain shackled in obsolete practices.

Taken together, population pressures, economic growth, inept politicians and geographical reality mean that in the foreseeable future, Indians cannot take their fundamental right to live in a clean, healthy environment for granted. In this long struggle, public interest litigation and judicial activism will continue to give Indians a fighting chance.

India’s leap to Euro VI standards is a stride in the right direction. Those on the front lines know that electric and autonomous cars represent new opportunities. “We don’t believe in replacing all Euro-VI compliant vehicles with electric vehicles,” says CSE’s Mukerjee. “We are looking at the future through the lens of shared mobility.”

Shared mobility for 1 billion-plus Indians? Now that will be another story.

Deepali Srivastava is a writer and editor whose articles on economic and environmental issues have appeared in Forbes Asia, MSNBC.com, and strategy-business.com. As founder and president of Script the Future, she also provides editorial services to organizations.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine