Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberEvery street tells a story, but there are some that capture an entire history. On Orchard Street in New York, tenement buildings that a century ago housed working-class immigrants and makeshift garment factories once represented the city’s industrial economic drivers. Now, as home to affluent professionals and sleek boutiques, the narrative has changed to reflect today’s white-collar, consumption-based economy. In Chicago, 47th Street has evolved along with the African-American community that made the corridor a center of commerce and culture upon arriving from the South during the Great Migration. After the 1950s, it became one of the many paradoxes of the Civil Rights movement, as relatively well-off blacks began moving into other neighborhoods from which they had hitherto been shut out, leaving disinvestment and blight behind.

In Newark, perhaps the most storied street is Halsey Street. Named after William Halsey, the city’s first mayor, Halsey Street served as the retail center of New Jersey’s largest city throughout much of the 20th century. Home to three major department stores and an iconic clock tower, this strip was for decades the place to see and be seen in Newark. Until Macy’s bought the regional department store Bambergers and whisked its Thanksgiving parade to Manhattan, the annual holiday rite began on the corner of Market and Halsey streets.

But by 1992, the Thanksgiving Day parade and the department stores that hosted it were a long-off memory. Retailers had followed the city’s middle class to the suburbs, leaving behind derelict buildings and wide, empty sidewalks. Nowhere has the decline of Newark been more apparent than on once-grand Halsey Street.

Until now. These days on the same thoroughfare, customers at a new lunch spot, The Coffee Cave, munch on jerk-turkey paninis in the shade of the abandoned edifice of Hahne & Co. department store. Down the block, another new dining spot, Cravings, counts Mayor Cory Booker as a fan. “This is just such an extraordinary contribution to what I believe is one of the most critical streets in our city,” Booker said at the restaurant’s 2010 opening.

All this points to a burgeoning regeneration of the street’s commercial life, a rebirth that holds implications for cities nationwide as well as for the future of business.

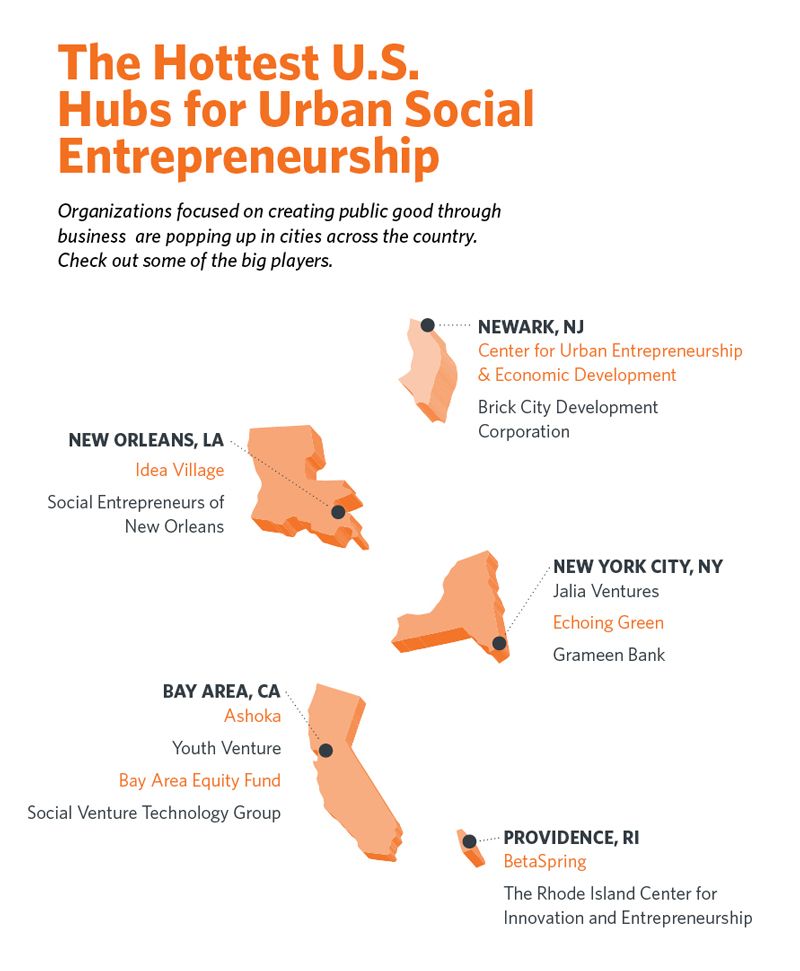

Throughout the past several years, entrepreneurship has risen to the level of choice buzzword among policymakers and politicians. Programs intended to spur or support entrepreneurship exist at all levels: Neighborhood, municipal, national. Some programs handpick businesses worthy of startup investment and guidance. Others target specific parts of cities, which often focus on areas like Halsey Street that suffer from severe disinvestment. For-profit entities looking squarely at these areas — including the 22-employee merchant bank Next Street and venture capital firms like Jalia Ventures — frame their work around what they call a “triple bottom line,” taking into account the social and environmental impact of their business as well as its profitability. In the case of Halsey Street, a rebound would likely not be happening without the support of a Harlem-raised former jewelry manufacturer named dt ogilvie (she doesn’t capitalize the letters in her name). ogilvie founded the Center for Urban Entrepreneurship & Economic Development at Rutgers Business School, and most recently became dean of the E. Philip Saunders College of Business at the Rochester Institute of Technology. In 2008, she began to eye the boarded-up avenue as a laboratory to test her center’s founding principle that small-scale urban entrepreneurs hold the key to unlocking neighborhood renewal.

“By concentrating on a small geographic area, you see traffic generators,” ogilvie said. “We believe that by helping people to grow businesses you create wealth, which inspires other people to grow businesses and generate more wealth.”

Newark’s biggest department stores operated on Halsey Street until the late 20th century, when the retailers followed middle-class city residents to the suburbs, building new outposts there while their old headquarters decayed downtown.

Over the next several years, CUEED has invested more than $1 million into the strip, much of it going toward funding four businesses: A coffeehouse, a caterer and restaurant, an art supply store and a print shop. All four still exist today. And their presence has drawn other businesses, not at all them funded by Rutgers.

Omar Sharif Townes is one of those entrepreneurs drawn to Halsey Street by the new commerce. There, in a storefront next to The Coffee Cave, he operates a second location for his popular Cut Creaters barbershop. “I saw growth back here and I saw a new community,” Townes said. A decade ago, he never would have predicted the move. “It was a desert [then]. There were no businesses here,” he said.

Townes’ story illustrates a phenomenon that an increasingly influential segment of urban economists have worked to prove for more than a decade — that for-profit enterprise is an efficient tool for generating wealth in urban cores. As economist Michael Porter wrote in “The Competitive Advantage of the Inner City,” an influential 1995 Harvard Business Review article: “A sustainable economic base can be created in the inner city, but only as it has been created elsewhere: through private, for-profit initiatives and investment based on economic self-interest and genuine advantage.”

In the decade that followed the appearance of Porter’s article, his words were credited with influencing the design of important public policy (including President Bill Clinton’s 2000 New Markets and Community Renewal legislation, which created tax incentives for businesses operating in distressed neighborhoods and expanded empowerment zones, creating more incentives for businesses in urban cores). Still today, Porter’s non-profit think tank, the Initiative for a Competitive Inner City (ICIC), compiles data on urban-based companies and promotes public policy to encourage more private investment in these areas. But even with its emphasis on economic return, ICIC believes a multiple bottom-line approach is essential to growing urban businesses, especially in today’s post-recession America. “I would hope that some day it would be possible to approach supporting inner-city businesses with a purely profit-based mindset,” said Mary Kay Leonard, ICIC president and CEO, in a recent interview.

Indeed, in many respects, simply setting up a business is a risky proposition. Fewer than half of all businesses established in 2010 remained in business a year later, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. And in the majority-black neighborhoods that comprise much of urban America, the challenges are particular and steep, thanks in large part to scars left by redlining. A 2010 report published by the Minority Business Development Agency concluded that black-owned companies have an average revenue level that’s one-sixth than that of the average of white-owned companies. Also noted in the MBDA report: Minority business owners make just 3.7 percent of all pitches to potential angel investors.

“We believe that by helping people to grow businesses you create wealth, which inspires other people to grow businesses and generate more wealth.”

Yet despite the hurdles, entrepreneurship is an attractive avenue to earning money in distressed urban environments where there simply aren’t many other clear avenues toward employment. And for many of these entrepreneurs, rewards are plentiful. In 2011, a study done by Porter’s group found that when compared to non-urban areas, cities boast a higher proportion of businesses that earn more than $100,000.

“If you look at the concept of risk, risk is something that people often misunderstand,” said Magnus Greaves, who runs the 100 Urban Entrepreneurs program, a nationwide initiative aimed at early-stage business owners in American cities. “If you are from a tough community and had a tough go of it, starting a company isn’t a scary proposition. If you have all this mentorship and guidance, you aren’t going to have as much risk.”

Whether considering all this from the vantage of Halsey Street or Wall Street, it’s obvious that urban entrepreneurs are critical to building stronger economies. The more support they receive, the less risky investments in their communities will seem. But right now, the big question is: Can betting on this class of people who are taking on economic risk be the way to deliver positive social impact to traditionally disadvantaged urban communities? Furthermore, how intertwined are the goals of making a profit and promoting social change in these neighborhoods? Must those goals be treated differently?

Urban entrepreneurship didn’t always need a hand from philanthropy. In fact, it wasn’t until the mid-20th century one-two punch of manufacturing’s decline and suburban flight that downtowns began to wane. As middle-class white families left the city for jobs and homes in the expanding suburbs, cities began to lose investment to redlining, a racist practice that declared entire communities, rather than individuals, ineligible for financial products. Technically such discriminatory practices were federally outlawed in the 1970s, but scarcity of such services continued by mere fact that banks weren’t naturally drawn to economically depressed areas.

Enter the social investing movement. In the 1980s, non-profits such as Ashoka and Echoing Green emerged with a mission to level the playing field between small-scale entrepreneurs and the business sector at large. While these organizations once focused on less-developed countries, over the years they expanded their attention to cities in industrial nations, including the United States. It’s safe to say these organizations laid the groundwork for the work that is being done on Halsey Street and across the country.

Kesha Cash serves as director of investments for Jalia Ventures, a venture capital firm that funds entrepreneurs of color, particularly those aiming to make a social impact in urban neighborhoods. Part of the larger Serious Change L.P., a $50 million fund that encompasses social entrepreneurship broadly (going beyond just cities), Jalia invests $250,000 to $500,000 in companies that have short histories and business models that signal future growth. Much of its attention has focused on New York City, which those involved in the firm know best. Their roster is impressive with financing going to the likes of Peartree Preschool, an eco-friendly school in Harlem, Return Textiles, a sustainable yarn and fabric company that hip-hop mogul Pharrell Williams also invested in, and Red Rabbit, an East Harlem-based provider of healthy and locally sourced school lunches.

Rhys Powell, founder and CEO of Red Rabbit, said his company connected with Jalia in 2010, at just the right time. “Other minority-owned, urban businesses…have struggled with finding the funding that is necessary for them to grow,” Powell said. Red Rabbit had “hit the same point when we were approached by Jalia.”

When Jalia approached Red Rabbit, the startup had only a few employees and contracts with 30 schools. The funding jolt allowed the company to pick up the pace of its growth. Today, Red Rabbit works with 70 schools in the New York City region. Rhys said his goal is to expand the reach of his company to other communities.

This past June, Jalia launched its $3.5 million Impact America initiative aimed at supporting budding social entrepreneurs at historically black colleges and universities. This variation in supporting businesses at various levels of development is important to Jalia’s mission. “In order to move the needle there needs to be that support at all levels,” Cash said.

Impact America will hold competitions similar to those held by 100 Urban Entrepreneurs, an Atlanta-based organization established in 2010. Supported by rapper Sean Combs and filmmaker Tyler Perry, 100 Urban Entrepreneurs holds elevator-pitch competitions that end with winners receiving up to $10,000 in startup funding, as well as technical assistance from a network of other businesses going through the same growing pains.

“If you are from a tough community and had a tough go of it, starting a company isn’t a scary proposition. If you have all this mentorship and guidance, you aren’t going to have as much risk.”

One urban entrepreneur helped out by Combs and Perry is Jennifer Burrell, an African-American Chicagoan and the owner of Frock Shop, a small clothing rental outpost based in Chicago’s Lower West Side. Burrell began her business in a makeshift store she ran out of a storage facility close to her home in a neighborhood south of downtown, otherwise bereft of economic activity. These days, her shop is in Pilsen, a post-industrial outpost of budding entrepreneurs and artists. Slightly bigger than the average closet, the shop is colorful and welcoming, with pink walls, a funky border trim and hundreds of bright, neatly hung dresses.

Burrell, who also works full-time in sales and marketing for a pizza company, put her $10,000 grant from 100 Urban Entrepreneurs toward buying more dresses and developing an e-commerce operation. “They really help small businesses think big,” Burrell said. “Urban Entrepreneurs is about networking within organization and getting access to their expertise within their network so you can grow and expand your business.”

“There are a lot of good urban, small businesses that deserve [such support],” she said.

In the jigsaw landscape of urban entrepreneurship, there is indeed a missing piece in the disparity between support resources and the need for them. These initiatives, while laudable, ultimately may not be broad-based enough to really make a difference in communities where deep structural challenges make the survival of any one business risky. Greaves acknowledges that a portion of grant recipients don’t make it past a first year of business. Those causalities, he says, come with the territory. “We’re often dealing with young, first-time entrepreneurs,” Greaves said. To him, the failure of a business doesn’t amount to a failure of the program. “By and large, it has been mostly success, but I don’t mind these failures,” he said. “These entrepreneurs are young and will get something out of the experience.”

Across the board, entrepreneurs who have received loans or support from social investing groups say it is this attitude of person-to-person support that defines the mode of lending.

“It wasn’t just that they were willing to give me a loan,” said Fauzia Abdur-Rahman, who runs two Jamaican-fusion food carts in the Bronx. “They work with you in terms of your business plan and how to construct your business.” Abdur-Rahman receives funding from ACCION USA, a microfinance organization that provides low-interest loans to entrepreneurs.

It’s no accident that Newark is emerging as a center for urban entrepreneurship. An inspirational figure known to save people from burning buildings and responding via Twitter to residents in need of snowplows, Mayor Cory Booker has made improving long-neglected neighborhoods his mission, and a big part of that is bringing them commerce and jobs. “When you create wealth and community like this, it has a multiplier effect,” Booker said at a recent press conference. “The dollars recycle within the community. It’s really the philosophy we take. It creates a dynamism that affects the whole city.”

In 2007, Booker established Brick City Development Corporation (BCDC), a quasi-governmental economic development arm that allowed his team to aim lending and other resources at new business owners. The administration looks at construction developments across Newark and luring businesses like Panasonic and Audible.com within its limits as victories that will reverberate throughout the city’s economy. But while the investment in corporate residents is nothing novel for a city, the twin emphasis on small-scale entrepreneurship is emblematic of Booker’s progressive approach to economic development.

Newark is a poor city. In 2010, its median household income was $36,000, compared to a national median income for all American households of $52,000 and $55,000 for Essex County, the largely suburban county that includes Newark, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. In March, the city’s unemployment rate was disturbingly steady at 14.5 percent, five percentage points higher than all of New Jersey and more than six percentage points higher than the nation as a whole. The population hovers around 277,000, more than a third less than the population recorded by the city at its peak in 1930.

Efforts to support entrepreneurs on Halsey Street have continued to draw small businesses such as art kitchen, pictured above.

Despite the grim numbers, City Hall officials and their allies, many handpicked by Booker, say the tide is turning. As evidence, they point to the big successes and developments of downtown. Among them are minority-owned restaurants across from the New Jersey Devils’ home ice at the Prudential Center and a new hotel along the city’s main drag, Broad Street. The hotel development is the first of its kind in 40 years. There are also plans for a $150 million development south of downtown that would house charter schools, schoolteachers and hopefully a number of retail options to sustain a new population.

Despite the high-profile groundbreakings, Newark has a long way to go. Downtown bustles, especially around the Prudential Center and Penn Station, the gateway to New York City. But walk a few blocks in any direction and the streets grow deserted and the storefronts humble, if they are open at all. Even the city’s most vocal boosters admit that big-ticket projects won’t transform the city without smaller-scale business openings in the neighborhoods outside of downtown. “When you think about great cities, it is the big companies, but it’s also the entrepreneurs throughout that matter,” said Lyneir Richardson, CEO of BCDC.

Richardson’s organization functions like economic development departments in other cities, except that it’s a non-profit corporation spun off from City Hall. Over the past five years, Brick City Development has lent out nearly $14 million to businesses in loans ranging from $40,000 to $2 million each. In the past year, BCDC has provided technical assistance to 130 aspiring entrepreneurs in town, and is preparing to provide a few with $5,000 startup grants. The biggest loans go to high-profile downtown businesses, big stores and major restaurants, though the organization makes room for the humbler businesses, such as one run by a woman who makes hand soaps and creams at home. Richardson said that BCDC’s impact is bridging entrepreneurial ambition with economic reality.

Among those with such ambition are Toxi Roane and Rick Richardson, who dream of opening a restaurant called The Fish Grill in the city’s South Ward, a part of town that hasn’t felt the economic effects of high-profile developments downtown. Rick Richardson (no relation to Lyneir Richardson) said BCDC’s technical assistance classes “got the ball rolling,” helping to solidify a business plan, put up cost and revenue projections and make a pitch to lenders. Roane said BCDC’s support was essential to start what she hoped would be a chain with “an upscale, classy interior with many varieties of healthy fish being served at a fast-food pace.”

Richardson agrees with Kesha Cash and others who say that access to capital is the biggest challenge facing these entrepreneurs. “Startup is the hardest financing to get,” he said, “They need support from organizations and government-based institutions like ours.”

“When you think about great cities, it’s not just about the big companies, but the little entrepreneurs,” said Richardson.

It’s not breaking news that businesses attract other businesses and that together, these small operations have the power to generate wealth. What is news are the resources that previously ignored or overlooked urban entrepreneurs are now from foundations, venture capitalists and even government.

Established in 1994, the Department of the Treasury’s Community Development Financial Institutions Fund gives financial assistance and information to community development financial institutions, or CDFIs, that function as financial institutions and credit lenders in disadvantaged areas. As of May 2010, there were 862 such CDFIs nationwide. These organizations range from entities that mimic the work of traditional banks, which unlike CDFIs don’t need to keep their funds within a specified community, to microfinancing organizations such as ACCION, which give small loans to new businesses when traditional banks won’t. Cumulatively, these smaller and less traditional banks hold great power; in April, banks with $10 billion in assets approved 10.6 percent of all loan requests while smaller banks approved 45.9 percent of loans. Alternative lenders approved 63 percent.

In addition to supporting non-traditional lending, the CDFI Fund also administers the federal New Markets Tax Credit program, which offers tax incentives to investors in low-income communities. Since the credits were established in 2000, the Treasury has given away more than $33 billion in tax benefits — and helped bring new investment to neighborhoods in New Orleans, Chicago and dozens of other cities. The program officially expired at the end of 2011, though the CDFI Fund continued by allocating $3.6 billion in tax credits in 2012. President Obama, who voiced support for CDFIs when he took office, included a $100 million boost to the program in the 2009 stimulus package. More recently, Obama’s proposal for the fiscal year 2013 budget includes $221 million for CDFIs, the same amount as allocated last year.

“When you think about great cities, it’s not just about the big companies, but the little entrepreneurs.”

In tandem with entrepreneurs like Abdur-Rahman, these government programs aspire to reshape the urban economy, and potentially usher in a new generation of market leaders. “There’s often an assumption that you need non-profits or the government to help the city,” said Tim Ferguson, founder of Next Street, a Boston-based commercial bank focused squarely on businesses based in urban areas, mostly in the Northeast. “At the end of the day, when you want to deal with poverty or other economic issues afflicting the same communities, you want to deal with it by building business. I don’t think social and for-profit goals are at odds at all.”

In other words, the important thing is putting a culture of entrepreneurship in place. For Magnus Greaves at 100 Urban Entrepreneurs, embedding the program more deeply in local urban ecosystems is its logical next step. He envisions storefronts where aspiring entrepreneurs could meet with mentors, receive technical assistance and learn about new avenues of funding.

The members of Booker’s economic team, as well their colleagues doing similar work around the country, believe that building businesses with a socially minded approach will transform cities. And indeed, there are signs on Halsey Street and similar places around the country that they are right. One thing is certain: There are plenty of budding entrepreneurs out there. What still must be determined is how best to ensure they the have the tools to beat the odds and survive.

Support can come from government-based entities, non-profit or for-profit sector alike, and will likely need to flow from all sources, if a movement is to truly reshape urban economies. The entrepreneurs on Halsey expect their street to continue its evolution with more businesses cropping up, and their own businesses growing.

Omar Sharif Townes, for one, is planning to approach traditional banks for funding. Cut Creaters, he said, can and will be a job creator for his city.

“People ask me, why do you keep investing in this town?” said Townes. “Well, there are six or seven McDonald’s in town. Why not six or seven Cut Creaters? I want to give to my community. I want to invest in my community.”

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Tanveer Ali is a multimedia journalist based in Chicago. His work has been featured on the Chicago News Cooperative, WBEZ, WhoRunsGov.com and Mashable, as well as in publications including the Columbia Journalism Review and GOOD. Tanveer is a graduate of Columbia University and the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University.

Adi Talwar is an award-winning photographer based in New York city. He shoots for various publications, corporate and non-profit clients. He is passionate about photographing people and capturing their emotions.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine