Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberLate morning on the first day of school this year in Jersey City, N.J., Paul Valleau sat in a café waiting for a bagel. Like any self-respecting, middle school-aged young man, he leaned far back in his chair, as if waiting for the two adults chatting nearby to say something patently ridiculous. Paul, 11, still seemed deep in summer, or just very hungry.

A few blocks away and two weeks later, in the waterfront city’s gentrifying Hamilton Park neighborhood, Molly Sheridan was checking on her cat and finishing up a Japanese manga volume of InuYasha. Molly stretched out on a comfortable chair, in shorts, and let the sun from the front windows catch her light brown hair. She had the luminous, permanently backlit skin of a preteen and the kind of wise-for-her-ages silence of a character out of a Bronte novel.

Molly looked across the room to the Eiffel Tower. The first third of it, en papier, sat on her dining room table, which doubled as a desk. She had climbed the real tower last year with her parents, on a rare whirlwind visit to France. She stared at the half-built tower and talked Minecraft, which is, she says, really cool because you can build whatever you want and choose the right metals for your blocks — not all of them are right. She wants to set up her own server to be a master. Like Paul, Molly is initially shy but easily conversational around adults, an age group both get to spend a lot of time with as homeschooled children.

Molly and Paul do school at home, at a time when doing school in school increasingly means taking tests, writing to rubrics and solving “real world” math problems on worksheets. They are city homeschoolers who live in apartments and use public transit and who defy the popular — and increasingly erroneous — stereotype of homeschooled children as the brood of fundamentalists off a country road, whose parents don’t want their kids exposed to evolution and Miley Cyrus. Or of a separatist sect taking their children’s education into their own hands: Think Amish, Mormon, Lubavitchers, fundamentalist Christians, off-the-grid hippie libertarians.

Far from disconnected protestors against the mainstream, urban homeschoolers use the city as a resource — and in turn, can become deeply embedded in the city’s wider life. Aleta Valleau, Paul’s mother, is someone who does everything so against the grain that she ends up a trendsetter. A working mom who co-owns Jersey City’s only bookstore, Tachair, she is gently, good-naturedly and near-singlehandedly yoking together a book culture for this city of a quarter million. A former teacher herself, she is in charge of Paul’s curriculum, although he is old enough now to make decisions about what to read or practice with her. Aleta’s mother and collaborator, Carol, is also a former teacher and runs the bookstore, which has become a central meeting place for local homeschoolers.

Paul has already raised more than $5,000 for the local library, continually threatened with shortened hours due to budget cuts, through a charity he started called Opus Jr. Last spring he got children’s book author R.L Stine to read at a fundraiser for the cause. Paul also works a plot at a community garden that opened last year in an empty lot that used to serve mainly as an open-air pissoir and thoroughfare to a local liquor store.

City kids who learn at home are relatively worldly, exposed daily to the complexity and social problems that densely populated areas make impossible to ignore. But they, and their parents, have withdrawn from one major element of that shared urban public sphere — the schools. They’ve made the decision for many reasons, but in a large part because these families have the confidence that they can do better by their kids. Nationally the number of homeschooling families has increased steadily, going from 13,000 in 1970 to about 2 million today, according to the National Home Education Research Institute (NHERI), or to 1.5 million if you believe the Department of Education. In total, homeschoolers represent almost 3.5 percent of the country’s school-age population. The Department of Education only started tracking homeschoolers by regional density in 2007 and found them distributed fairly equally in thirds among rural areas, suburbs, and cities and towns.

Exact numbers of homeschoolers are hard to come by in New Jersey, the most heavily urbanized state in the country, where families don’t need to report to the department of education or even local boards if they opt out. Estimates from NHERI founder and president Brian Ray put the number at between 35,000 and 47,000 out of 1.36 million schoolchildren. On a local level, the Jersey City Board of Education reports varying numbers of homeschoolers, from a high of 47 in 2011 to only 12 this year. But that represents, in the main, those students who leave the public schools in any given year and must say why. Various Yahoo groups and Meet Up pages for homeschoolers in the area have dozens of names, and several local families say they never informed the local BOE one way or the other. In neighboring New York City, where families must report, 2,766 school-age children were homeschooled in 2011-2012, versus 1 million in the schools — a rate of around one-quarter of a percent and lower than the national average. City homeschoolers have not yet reached the mainstream, but their numbers are trending upward.

Most striking in the Department of Education data is the upward trend of parent income and educational attainment. In 2003, homeschooling parents came from all income strata relatively equally. By 2007, more families were upper income, with about a third making more than $75,000 a year. They tend to be well educated, with 50 percent possessing a bachelor’s or higher, compared to 28 percent in the general population. And this figure has climbed further. Ray conducted a 2010 study that found 65-66 percent of homeschooling parents have at least a bachelor’s degree, compared to less than 30 percent of the general population. Most are married, with mothers taking on the homeschooling duties. While only about a quarter of homeschooling families call themselves secular, many of these are urban.

Inside Tachair, a Jersey City bookstore-café co-owned by Aleta and her mother Carol.

The trend toward more educated, middle-class homeschooling parents should give high-poverty city school systems pause, since the success of these districts hinges in large part on wooing the same demographic. In Jersey City public schools, 75 percent of students receive free or reduced lunch, the standard measure of poverty in schools. Citywide, just 40 percent of households with school-age children had incomes low enough to qualify, indicating a large disparity between the city and school district’s poverty rate. Many urban districts have tried to entice the middle class to stay through magnet schools or other marketing efforts, such as Philadelphia’s Center City Schools Initiative, since reducing poverty in schools goes a long way toward lifting achievement for all.

(Scholar Richard Kahlenberg has examined this at length, and defines middle-class schools as having less than 50 percent of students eligible for free and reduced lunch. “Socioeconomic integration is one of the most important tools available for improving the academic achievement, and life chances, of students,” he wrote in the winter 2012-2013 issue of American Educator.)

“I would love to see more involved, invested parents opt into public schools,” says Ellen Simon, a downtown Jersey City parent of a young child in public school and a newly elected member to the Board of Education. “That’s one of the things that will improve public education for everyone. There used to be a population that just moved away when their kids became school aged. We are seeing more people staying.” Evidence of that comes from the burgeoning demand for the city’s excellent, free prekindergarten program. Simon’s son’s school, PS 5, has had to add four pre-K classrooms for 3-year-olds, up from one three years ago.

In the public conversation about potential upsides to gentrification, the assumption is often that middle-class families staying in central cities will be a force in public schools. But many parents have had enough of the increasing conformity required of common standards and high-stakes tests, and the very real consequences low-performing districts face for not upping their scores. Some protest by keeping their children home on standardized test days. Others pull together low-stress, enriched, project-based days for their children at home. Arguably, instead of advocating for better public schools for all children, these homeschooling parents are choosing to opt out and build a private-sector alternative that exists on a spectrum of choice, from private to charter to public.

Far from disconnected protestors against the mainstream, urban homeschoolers use the city as a resource — and in turn, can become deeply embedded in the city’s wider life.

Today, homeschooling holds allure as a symbol of radical independent-mindedness. Part of it is the attraction of going off the grid in an increasingly boxed and gridded world. It affords the luxury of time — time to read a book during the day or build a garden or form a charity at the age of eight. But does a parent who knows the benefits of a great education so much that she is willing to set aside her own time to learn with her child owe anything to students other her own? And how bad must a school be to explain giving up on the whole premise?

While homeschooling families are rare enough that they by no means represent a mass exodus from urban schools, the attraction of doing it yourself for educated parents does, however, represent an ongoing failure of the public system to portray itself as a defender of idiosyncrasy and individuality. Urban homeschoolers don’t reject society. They embrace it — they chose to live in densely populated cities, after all. But they do reject the one-size-fits-all, industrial-era schooling model that they see as a hallmark of universal education in the U.S., particularly in city systems anxious about preparing high-poverty students for success on state tests.

Molly attended pre-K and early grades at the nearby public school for 5.5 years until the fourth grade, when she and mother, Becky, realized that going to school every day was an exercise in misery.

“In first grade, the teacher says, ‘I see we have a square peg. That’s not going to work.’ In third grade, the teacher would turn her desk to the wall,” Becky says. “They took a happy-go-lucky, inquisitive girl and turned her into a sad, anxious child. Let’s get back to love of knowledge, a thirst for knowledge.”

Keeping children on grade level, across subjects, in order to “meet standards” is one of the main undertakings of schools these days. The 2001 passage of the No Child Left Behind Act ushered in a new era of accountability, a business term applied now to the fuzzy enterprise of inculcating insight in young minds. Students from third grade on up needed to take annual tests, where their scores served as referenda on their schools, which stood to lose funding if they didn’t keep up.

Under the Obama administration the testing mania has only increased, even as many of the NCLB’s mandates, such as the statistically impossible requirement that all students show 100 percent proficiency by 2014, have been abandoned. Now states administer tests to judge the effectiveness of teachers, making the annual ritual that much more fraught and high-stakes in classrooms. With the slow rollout of Common Core Standards-aligned tests in 45 states, new tests for every grade in English, math and science will decide the fate of teachers as well as students.

Many parents want no part of this. Of the half-dozen families I spoke with, and across many homeschooling message boards in the area, parents emphasize that they didn’t run away from testing because their children can’t do well, but because their children can. These parents want a less rigid schedule of learning for their curious, already learning children. “He could already read,” Aleta says of her son at five years old. “We needed flexibility because he was gifted for one area and then average for another. I think most kids are like that. One teacher said, ‘You know, my daughter was gifted, too, but by the time she was in third grade she evened out.’ And I thought, that’s horrible.”

To be fair, many good public and private schools across the country eschew these hallmarks of standardization. Most urban public schools, however, don’t have that luxury. Under No Child Left Behind and later under the Obama administration’s Race to the Top mix of incentives and penalties, schools that fail to raise student performance, as judged by test scores, face diminished funding and even closure. This is either highly motivating or dispiriting, depending on your perspective.

Either way, the threat looms. Five Jersey City schools are New Jersey “priority” schools, which means they fall in the bottom 5 percent of performers in the state and risk closure if they don’t improve within two years. In 1989, the city’s schools were the first in the nation to undergo a state takeover due to poor performance. To this day, the state of New Jersey still runs three of five local board of education functions. In a major coup for “local control” two years ago, the elected board was able to choose a superintendent for the first time since 1989, selecting a former New York City and Delaware deputy superintendent named Marcia Lyles. She has already made improving high dropout rates and low test scores her priorities.

But this is not nearly enough for committed homeschooling parents, such as Aleta and Becky and the dozens who attend Aleta’s science and book clubs at Tachair. Their concerns focus more on respect for individual learners. To woo them, public schools would probably have to offer comprehensive magnet Montessoris, with tiny student-teacher ratios and where children learn at their own pace and engage in lengthy projects — an approach unlikely to appear anytime soon in a district where up to 60 percent of students are below grade level, depending on the subject and grade.

Paul, 11, has never attended school. “The concept of a place where education is available to anyone who wants it is fantastic,” says Aleta, his mother. “But school has turned into a lot of dysfunctional things instead.”

Paul never went to school, not in San Jose, Calif. nor in Princeton, N.J., where he had lived before. But Molly spent the first years of her educational odyssey inside the public school down the block, which has a “not-so-bad” reputation among Jersey City’s growing New York-commuter class with children. In P.S. 37, also known as Cordero, 54 percent of students are economically disadvantaged and just 50 percent met standards for proficiency in language arts in 2011-12, while 60 percent were proficient in math. (In New Jersey, proficiency indicates grade-level standards, as the state transitions to the Common Core Standards next year.)

Rusty pedagogy, however, was not what drove Molly away in the end. The breaking point, Becky says, was the “chicken nugget” incident. In the third grade, another girl tried to force-feed a chicken nugget to Molly, who is vegetarian. The vice principal brought both girls up at once to give their accounts at the same time. “I said, ‘we’re done,’” says Becky, who previously worked as a child-care provider, which she still does part-time. For her part, Molly says she has no desire to go back to school. She sees plenty of friends in the park or on outings to Aleta’s bookstore, which holds a weekly book club for kids and a semi-monthly science club.

At home, the Eiffel Tower progresses slowly. October is all things French, Becky explains. Scented candles set the mood, as Becky looks for a chanson on the iPod and Molly digs out a French bread recipe on the iPhone. Molly asks the phone: “What is water in French?”

“How many ingredients?” Becky calls out from the kitchen, in a little alcove off the main room.

“Six.”

“How many were in the one we bought at Key Foods?” She hands Molly the empty bread bag.

“Twenty-five.”

Becky gives her a significant look. Molly gets the lesson.

Molly asks Siri the words for salt, egg and sugar in French, and haltingly pronounces them on her own.

The heart of the lesson, as with the bread itself, is the yeast. Molly guesses warm water and sugar will help it grow. Her mother applauds the intuition. Books spill off the shelves into a curriculum area, where an illustrated edition of The Odyssey sits near a math series called Life of Fred, which is written like a novel with some word problems thrown in.

As the bread bakes, Molly paints the tower. Behind her on the bookshelf sits a completed, intricate paper London Bridge that, Becky points out, took way too much adult help.

“Why does everyone think it’s silver?” Molly asks of the Eiffel Tower. “It’s bronze.”

“Just like the Golden Gate isn’t gold,” Becky says. “It’s named for the sunset. How many tons of paint does the Eiffel Tower need each year?” The phone comes out again. “55 tons. So how much paint is that?”

These kinds of parent-child conversations are the ones many of us reserve for the weekends or the ride to school. For homeschoolers, the days open up. Lessons only take so long — conversation and projects fill their place. Molly and Becky will return to the art store this afternoon, for more paint. Later, they may head to the park to watch some kids that Becky often takes care of.

“The only thing I learned in art at school was you use one side of the brush, then the other,” Molly says.

“We needed flexibility because he was gifted for one area and then average for another. I think most kids are like that. One teacher said, ‘You know, my daughter was gifted, too, but by the time she was in third grade she evened out.’ And I thought, that’s horrible.”

At Aleta’s apartment about five blocks away, Paul sits on the couch and surfs YouTube on a flat screen TV. He’s looking for the next video in a series called “How to Architect.” He has already done the first sketch for a dream house and needs to move on to putting in HVAC, on paper. The Internet, widely used, has been great liberator for homeschoolers. As Paul surfs, Aleta pulls together journal prompts she has cut out and stored in an envelope for him to use as he reads Paulo Coehlo’s The Alchemist. Paul’s dog, a highly communicative dachshund, snorts and stretches along his feet.

Aleta checks his answers from the previous day to problems in a basic college algebra textbook. She points out where he keeps doing a procedure wrong, and after a prompt or two he leans over to correct it. While some companies, such as the for-profit K12 Inc., are trying to leap into the market opportunity virtual homeschooling offers, these parents avoid canned curriculum. K12 tried to start charter schools in Newark last year — if approved, it would receive state money per pupil — but has not yet been successful proving to the Department of Education and the legislature that it can effectively educate children through a wholly virtual school.

Nearby, also in Cordero’s catchment area, lives Vikki Michalios, an artist, with her two daughters and husband. Michalios homeschooled her youngest daughter for two years and pulled her older daughter out of a charter school to join them. The two young girls attended Aleta’s sign language class and book club out at Tachair. They also would go to Manhattan, just 15 minutes away on public transit, to meet up with other homeschoolers in Central Park, or work on an extensive vertical garden in the family’s backyard. Within walking distance were dance classes, theater classes just for homeschoolers in Jersey City, capoeira and the library.

After the two or three hours of school at home, the children move out into the world. The gardens they built are the best physical evidence of their transformation of the place. Paul and Aleta have painted the raised wooden box in the former empty lot. Watermelons and tomatoes grew inside this summer. Michalios had 50 varieties in the vertical garden in the yard. The girls would draw pictures and identify plant parts, then ask why the soil for their garden was purchased. Since their yard flanks a former raised railway, which local activists have been trying to turn into a High Line-esque pedestrian park, the land was contaminated with coal dust. It is still the city, after all.

Although both Paul and Molly live in modest apartments, their neighborhood, Hamilton Park, is rapidly gentrifying. Apartments here can command rents comparable to parts of Brooklyn. Since the 1980s and the transformation of the derelict local waterfront with tall condos, young professionals — writers, teachers, tech workers — have been moving to Jersey City to find a bigger home in the greater New York City area. A few years in, many have suddenly found themselves with children. This educated class has choice in schooling: They can give public or charter schools a go, move to a suburb, scrape together tuition for private school, or opt out and do it themselves.

The latter choice is not an altogether new one for educated parents. Learning from a parent — or a tutor, if you were upper class — was actually the principal means of acquiring an education prior to the spread of schoolhouses in the 19th century. We know from the essays of Montaigne and Rousseau of their elaborate educations at home in pre-revolutionary France. Yet in the U.S., 19th-century reformers such as Horace Mann argued for the benefits to democracy of state-sponsored schools. “Under a republican government, it seems clear that the minimum of this education can never be less than such as is sufficient to qualify each citizen for the civil and social duties he will be called to discharge,” Mann wrote to the Massachusetts Board of Education in 1846. The Massachusetts legislature eventually responded by passing the nation’s first compulsory attendance law, and by 1918 all states except Alaska had passed legislation requiring children to go to school.

The move toward mandatory public education was implicitly about creating a common American identity. Public schools were a way to assimilate immigrants into the “melting pot” while offering a ladder for economic mobility. The very low numbers of homeschoolers until the 1970s were perhaps a testament to how much everyone bought in to the democratizing and elevating potential of public schools.

Becky and Molly in preparation for Halloween, painting a staff for a costume.

In cities today, the educated classes know they have choices, including the choice to withdraw from schools they feel are not fulfilling this democratic requirement well enough for their child. But for those who do go the DIY route, the choice doesn’t feel like a move away from socialization and integration with the larger world, but rather, they say, the opposite. “I homeschool because I want him to have better social skills,” says Aleta, who points out that the standard school structure of one teacher with 20 or more kids is an artificial social setting in which the children have little authentic interaction. Her children engage with other neighborhood kids at the music school, in dance classes, at the park. Just as if they attended the local public school, and more so than in the local private schools, the economic diversity of these homeschoolers’ peers is more determined by neighborhood than school — and this swath of downtown has been in the midst of wholesale gentrification for a decade.

But these choices are in fact political, according to Henry Levin, professor of economics and education at Columbia University and director of the National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education. “If we go back to the distant past, the main purpose of education was not to prepare people for the workforce, was not to maximize achievement, but really to maximize social cohesion,” Levin says. “The idea that people should be able to choose the kind of educational experience they want for their children and it’s up to them — that loses completely that idea of schooling for social cohesion and creating a strong society and a society that can work together.” (Full disclosure: For a brief time many years ago, Levin was my boss when I worked as an undergraduate for his Accelerated Schools Project.)

If families able to give their own children an education through other means abandon the schools, then the schools are clearly losing a resource.

Many homeschooling parents agree with Levin’s critique of the idea of education as solely preparing a child for a life of wage work. “We believe in the public school, the common school, but the public in public school no longer exists,” says Darryl DeMarzio, associate professor of education at the University of Scranton and the parent of two young children. DeMarzio is speaking of his own family but also, in a sense, for parents skeptical of recent market-based trends in education. Separately, Aleta Valleau echoes his sentiments. “The concept of a place where education is available to anyone who wants it is fantastic, but school has turned into a lot of dysfunctional things instead,” she says. “The school system does not deliver an education to every student. It’s impossible to give that responsibility to a teacher on a ratio of one or two to 30. Even children can’t be forced to do or learn anything that they don’t want to.”

DeMarzio identifies that dysfunction as, in a large part, an overreliance on the discourse of choice as a more conservative “entrepreneurial view of your children.” There’s this prevailing idea, he points out, that parents need to “invest” in their children’s education and have the freedom to make choices in schooling, as if schools were just another consumer product. “But I also believe choice and freedom in education should be about taking forms of action that have to do with reforming or transforming educational systems,” DeMarzio says. “So homeschooling as a form of action could be a kind of subversive act.”

This past summer, Jersey City elected Steven Fulop, a former Goldman Sachs trader and city councilmember, as its new mayor. Fulop won in large part thanks to the growing class of educated parents in the city’s gentrified downtown area. These families tend to like a mayor who adeptly walks the fine line of embracing the language of school reform (support of charter schools, teacher accountability and “innovation”) and supporting the public workers and district schools that educate 28,000 children.

“I view how a parent decides to educate their child as a personal decision, whether it be public, private or homeschooling,” Fulop says. “I consider these all personal choices, and definitely homeschooling is another choice on the spectrum. As the mayor of Jersey City, I value any parent’s choice, but my mission remains committed to the best possible public education for our entire city and all of its families.”

The new mayor, new superintendent, new Board of Education and, perhaps most off all, the new sense of Jersey City as a desirable place to live may in fact have made the local public schools more appealing in the last year. It’s notable that the spike in declared Jersey City homeschoolers — most likely those families already in public school who have to say that they are leaving — occurred in 2011, the year a newly empowered board fired the previous state-appointed superintendent. In the most recent two years, declared homeschoolers have decreased dramatically, from that 47 to 18 and then 12.

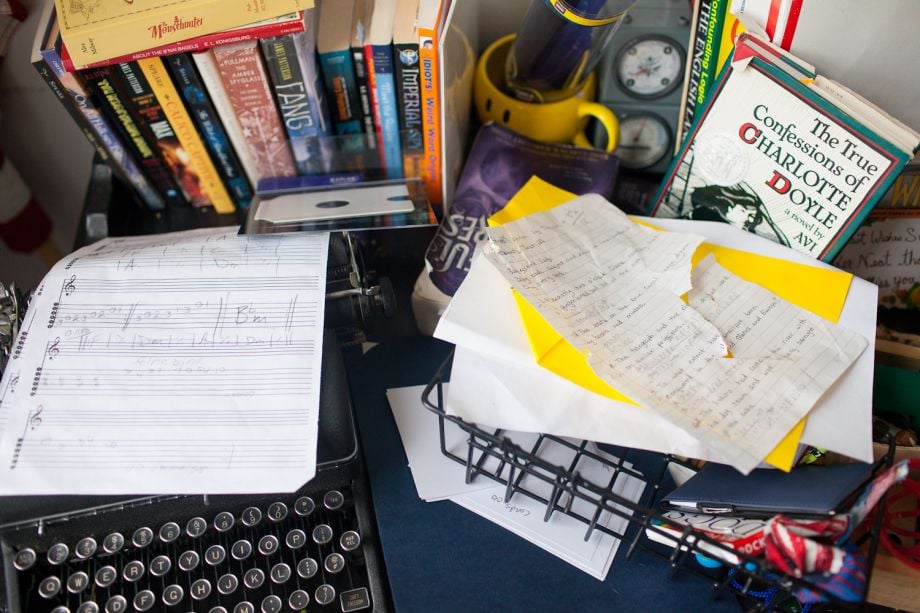

Paul’s desk. When he was eight years old, Paul started his own charity, Opus Jr., to raise money for libraries. He’s raised more than $5,000 to date.

Could the stemming tide of homeschoolers speak to a tentative confidence in the city’s schools at a moment of historic change, as a new superintendent and mayor attempt to cater to both a gentrifying class of parents with choice and the more impoverished, less mobile parents uptown? (A spokesperson for the BOE says they have no information to account for the fluctuating numbers.) Parents such as Simon are cautiously optimistic about the potential for public schools to cater to their expectations of more open, exploratory learning. City schools may one day be strong and diverse enough in their methods to keep even the most disinterested students, from skeptical high schoolers to elementary students who want to draw string beans uninterrupted.

Many homeschooling parents, such as Sheridan, Michalios and Valleau, a former teacher herself, still feel a nagging loyalty to perfect that grand experiment we began two centuries ago called school. It may be a flawed mechanism to transmit democracy and opportunity, but currently, in our poorest cities, it is the closest thing available. The difficulty faced by poor families in helping their children approach the literacy of education-rich families can feel insurmountable, yet city schools keep welcoming legions of kindergartners who are not yet reading on their own. If families able to give their own children an education through other means abandon the schools, then the schools are clearly losing a resource.

But even if 50 homeschooling families joined the 28,000 children of Jersey City public schools, they would not budge the socioeconomic makeup of the district. The parents may be potential catalysts, but at present they are serving as examples by standing apart, not by joining in. They are like canaries for a school district struggling to right itself, singing a subversive gospel of another kind of education, with tests, homework and grades replaced by reading, watching, responding, building, making and doing. It is the kind of school many parents dream of for their children, if only each child had all the time and attention a single devoted adult can give. Yet since no school district will ever be able to budget one-to-one ratios, it can approximate by experimenting — running “How to Architect” mini-modules, perhaps, or bringing back serious home ec as applied math, rather than paying for rote curricula from education software conglomerates. It takes a truly visionary leader to find, within existing constraints, the freedom to tinker.

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Carly Berwick writes about education and culture for Next City, as well as The New York Times, ARTnews, and other publications.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine