Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

AP Photo/Wayne Parry

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberOur new book, “The Arsenal of Exclusion & Inclusion,” examines some of the policies, practices and physical artifacts that have been used in the United States by planners, policymakers, developers, real estate brokers, community activists, and others to draw, erase or redraw the lines that divide. The book inventories these weapons of exclusion and inclusion, describes how they have been used, and speculates about how they might be deployed (or retired) for the sake of more open cities in which more people have more access to more places.

This small excerpt compiles some of the legitimate and illegitimate ways in which homeowners, municipal governments, and others restrict and expand access to a particularly contentious urban typology: the beach. We show in our book how access to parks, plazas, sidewalks and other inland urban spaces is controlled through things such as loitering ordinances, curfews, sidewalk management plans, busking bans and uncomfortable furniture. But the beach comes with its own set of contentious and often discriminatory policies, practices and objects that determine who gets to relax where, how and for how long. The beach is synonymous with fun and sun, and is of course where millions escape to on hot, summer weekends. But don’t let its carefree, breezy edifice fool you: The beach on which you are building sandcastles, body surfing and sunbathing is built on a battlefield.

The battle lines were drawn in 535 A.D., when the Byzantine Emperor Justinian declared in his Institutes that:

By the law of nature these things are common to all mankind — the air, running water, the sea and consequently the shores of the sea. No one, therefore, is forbidden to approach the seashore, provided that he respects habitations, monuments and the buildings, which are not, like the sea, subject only to the law of nations.

This “public trust doctrine” evolved into a legal principle that establishes rivers, oceans and other bodies of water as a commons to be enjoyed by all citizens equally — for recreation, fishing, navigation and commerce. Accordingly, jurisdictions that adopt the public trust doctrine (including the United States) are responsible for maintaining their accessibility and preserving their ecological integrity. Public trust lands typically extend to the “mean high tide” mark, which is the average elevation water reaches at high tide. The lands beneath waterways cannot be bought and sold either, except under circumstances where the public stands to benefit from their privatization. Public and private landowners may own properties adjacent to or even slightly past the mean high tide line, but they may not keep the public from accessing it.

That doesn’t mean they won’t try, as any beachgoer who has encountered a “PRIVATE ACCESS: RESIDENTS ONLY” sign knows. Residents who assume — wrongly — that the right to the beach is theirs and theirs alone will go to great lengths to defend their beach against perceived outsiders. In 1995, Michael Moore’s short-lived newsmagazine television show TV Nation staged an experiment: What if, on a hot summer day, a busload of racially diverse New York City residents tried to access the “public” beaches of wealthy, white Greenwich, Connecticut? After an unsuccessful attempt to enter the beach from the parking lot, the group boards a tugboat and, a mile offshore, gets into dinghies to start paddling toward the idyllic coastline. Minutes later, the Greenwich police arrive and form a barricade, prompting the New Yorkers to jump in the water and swim to the beach, where they are booed, accused of ruining a holiday, and threatened with arrest. “If you like the lovely beach, why don’t you buy some property in Greenwich, pay taxes, and come here and enjoy it,” exclaims one beachgoer. “I don’t see why we’re making a big fuss over this,” says another. “Just get ’em out. Have ’em arrested and throw ’em out.”

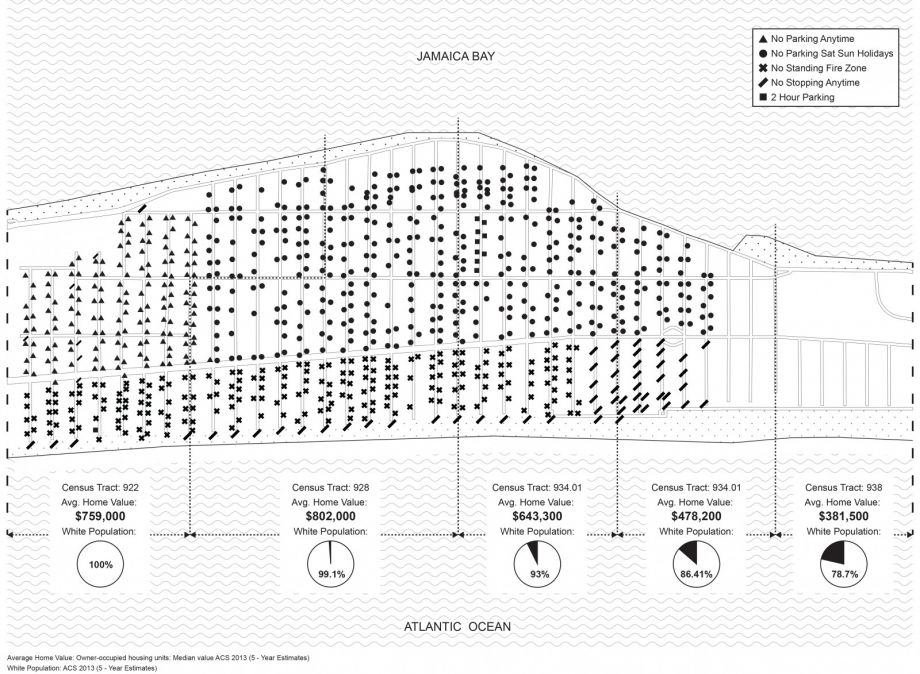

In the interest of not attracting the attention of beach access advocates, others use more covert tactics to defend “their” beach. Beachfront communities in most cases do nothing illegal when they institute a “residential parking program” on their streets, don’t provide public parking, or pass on a bus or rail stop that might provide non-residents with beach access. Maximum one- and two-hour parking spots are another way to offer public parking, without allowing them to be “gobbled up by beachgoers,” effectively preventing a nonresident from having his or her day at the beach and functioning as a tool of exclusion. Continue reading for a few more.

_920_613_80.jpg)

A booth wards off would-be beachgoers who don't have tags. (Credit: Interboro)

Beach tags and badges are used by municipalities, private homeowners’ associations, and clubs and resorts to restrict access to beaches, swimming pools, and other recreational amenities to residents and their guests, dues-paying club members, or hotel and resort patrons. Depending on state laws, coastal municipalities may allocate a certain number of beach tags to each resident as a privilege of residence that is unavailable to nonresidents. In other cases, tags may be available to residents and nonresidents alike for a fee. Among private clubs and homeowners’ associations, tags are rarely made available to nonmembers except as approved guests of members. On private or restricted-access public beaches, the wearing of a beach tag on a bathing suit signals to police or security guards a person’s right to occupy space on the beach. Failure to display a beach tag often results in a person’s forced removal and/or court-ordered fine. The use of beach tags is most prevalent in coastal municipalities and private, gated communities located in areas with high population densities and less-affluent, inland municipalities nearby. Other variants on the beach tag include bumper stickers or windshield emblems, wristbands and “dog tags.” The display of these markers, whether on one’s car or person, not only denotes one’s right to occupy a beach to law enforcement officials but also one’s status as a member of a private club or exclusive municipality. The power of beach tags as a weapon of exclusion (and exclusivity) thus extends far beyond the beach itself.

The use of beach tags proliferated in the 1960s and 1970s in suburban municipalities in the densely populated northeastern corridor stretching from New Jersey to Connecticut. The wealthy municipalities along Connecticut’s Gold Coast adopted some of the more extreme measures of exclusion, allocating beach access permits to residents only, installing guarded gates at points of entry, and aggressively patrolling beaches for violators. In this respect, beach tags were part of the arsenal of weapons used by wealthy and upper-middle-class communities to hoard taxes and resources, limit contact with inner-city residents, and reinforce the urban-suburban divide. It is important to note that the use of beach tags is rare in highly exclusive but remote summer communities where distance from urban populations serves as an effective means of exclusion.

While the use of beach tags and related weapons of exclusion was first adopted by wealthy and upper-middle-class coastal suburbs and gated communities, in recent decades beach tags have become a common weapon of exclusion used by planned communities situated along manmade lakes in which exclusive access to recreational amenities constitute a chief privilege of homeownership closely tied to real estate values.

The implementation of beach tags did not, however, go unchallenged. The public trust doctrine, a descendent of Roman law that became incorporated into American constitutional law, entrusts shorelines to the state for public use and, in theory, limits the ability of coastal municipalities and property owners to prevent public access. Legal challenges to the use of beach tags have often invoked the public trust doctrine to argue against the right of municipalities or private homeowners’ associations to restrict access to this public resource. Beginning in the late 1960s, an open beaches movement spread across the United States. Groups staged direct actions against restrictive beaches (including wade-ins and amphibious landings) and lobbied state legislatures to pass amendments ensuring the public’s right to access shorelines. As a result, the states of Texas, California, and Oregon passed open beach laws, but efforts to pass a national open beach act failed. Defenders of beach tags (and fees for beach access) have, in turn, argued that the cost of maintenance and staffing warrants their use and that without restrictive access policies, beaches would become overcrowded and, as a result, suffer environmental damage. In Borough of Neptune City v. Borough of Avon-by-the-Sea (1972), the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled that municipalities may charge fees to access public beaches but may not discriminate between residents and nonresidents. Though ostensibly open to residents and nonresidents alike, the requirement to purchase a beach tag results in a form of exclusion by income. In 2001, the Connecticut Supreme Court ruled in Leydon v. Greenwich that municipalities cannot enforce laws restricting access to public beaches to residents only. As a result of court decisions protecting the public’s right to access beaches, municipalities have adopted more subtle, but no less effective, means of exclusion, including severely limiting the availability of public parking and public restrooms in beachfront areas, enforcing prohibitions against wearing bathing suits on town streets, and passing laws against consumption of food or drink or playing of loud music on the beach. - Andrew W. Kahrl

Beach wheelchairs can allow more people to access the sand and water. (Credit: Interboro)

For individuals who use wheelchairs, accessing beaches is never easy and is often virtually impossible. Although beach wheelchairs don’t remove obstacles like dunes or stairs, their design enables users to move easily through sand, gravel, uneven terrain and even very shallow water. Models are generally made from lightweight PVC tubing and feature adjustable footrests, safety restraints, anti-roll handles, removable umbrellas, and extra-wide wheels for sandy landscapes. Some are even motorized. Others can float. Currently, beach wheelchairs are available to rent at many coastal sites across the country, from Santa Monica to South Carolina.

However, beach wheelchairs don’t come cheap. Purchasing one can cost thousands of dollars, and daily rentals range from $30 to more than $100. Alternatively, “Beachwheels,” a program in Long Beach Island, New Jersey, rents out beach wheelchairs free of charge. Thanks to local donations, it boasts five wheelchairs for children and 34 for adults, with one specifically designed for fishing. Each is available to rent on a weekly basis, delivery and pickup included.

A well-established sand dune is seen in Seaside Park, New Jersey. (AP Photo/Wayne Parry)

In 2006, USACE initiated a series of dune construction projects to shield New Jersey’s coastal communities from future storms. But USACE would only build dunes on the condition that shore towns become more accessible to the general public. Specifically, USACE required that communities submit to the public trust doctrine, thereby ensuring “public access, use and enjoyment of the beach and ocean.” Depending on the state’s discretion, enforcing the public trust doctrine might mean expanding nearby parking options, installing public bathrooms adjacent to the beach, building boardwalks, or simply eliminating physical barriers to public access. Importantly, much of the land upon which dune construction would take place belonged to beachfront homeowners, who had to sign contracts granting USACE permission to use sections of their property to create dunes.

In wealthy towns like Harvey Cedars and Mantoloking, New Jersey homeowners have cited a range of excuses for refusing to sign the easement contracts, even after the destruction wrought by Hurricane Sandy. For example, property owners argue that the manmade dunes will block their views of the ocean and thereby diminish the value of their homes or that the government contracts are too one-sided by granting the easements in perpetuity.

Additionally, many homeowners worry about the public trust doctrine being included in the contracts and would rather turn down the federal money than open up “their” beaches to the wider public. Most often, property owners have simply refused dune construction outright, putting their homes (and their communities) at risk. As of this writing, the Office of the Attorney General of New Jersey has begun using its power of eminent domain against the hundreds of “selfish” property owners who continue to stand in the way of a more comprehensive dune system along the shoreline.

_920_725_80.jpg)

A “fire zone” keeps outsiders from parking in this beachside neighborhood. (Credit: Interboro)

Back in May 2010, we noticed something strange in Rockaway, Queens. On the peninsula’s most exclusive, mansion-lined streets abutting the beach, not a single parked car was to be found. How was this possible on public New York City streets?

According to a series of signs, the area was a “Fire Zone” and parking was prohibited at all times. But what exactly were fire zones, and why were they only located in the wealthiest neighborhoods in Rockaway?

Belle Harbor and Neponsit are two of the whitest, most affluent neighborhoods on the Rockaway Peninsula in Queens, New York. They share a pristine strip of beach, which since 1939 has been owned and managed by New York City’s Department of Parks and Recreation. However, due to strict parking regulations, accessing the public beach as a non-resident is no easy task. On most residential blocks, signs declare that street parking is banned from May 15 to September 30; on others, parking is prohibited during weekends and holidays. Lean Locke, publisher of local newspaper The Wave, says that the parking restrictions were first implemented in the 1930s, when a number of judges and borough presidents called the area home. He speculates that the signs are too exclusionary to be erected today. Oddly, the city’s Department of Transportation has no record of most of them even existing.

Meanwhile, on more than 20 blocks of dead-end streets abutting the beach, other signs forbid parking year round. “No Standing/Fire Zone,” they read. Transportation officials have explained that if cars were allowed to park on the street, there would be no room for emergency vehicles (e.g., fire trucks) to turn around. That sounds reasonable enough. But why don’t the signs appear on the Department of Transportation’s website? And why is it that directly across the Belle Harbor–Rockaway Park border (the latter neighborhood being substantially less affluent), there’s no “Fire Zone” signage, despite the streets being the same relative width? Ultimately, given the neighborhoods’ stance toward non-residents, it doesn’t take a conspiracy theorist to sense a fake sign conspiracy.

A fake garage blocks beach access. (Credit: Interboro)

For those outside the top 1 percent, accessing Malibu’s public beaches can feel a lot like breaking the law. Hundreds of fake “No Parking,” “No Trespassing,” and “Private Property” signs litter the coastal strip. And fake signs are not the only decoy deployed by Malibu residents against the beach-going masses. One media mogul’s beachside mansion features a fake four-car garage and corresponding curb cuts which prevent beachgoers from parking near a public path, located directly next to the celebrity’s home.

The Los Angeles Urban Rangers lead a tour of Malibu beaches. (Credit: Los Angeles Urban Rangers)

Using maps and guided tours (called “safaris”), the Los Angeles Urban Rangers demystify Malibu’s 20 miles of beaches by identifying public spaces, access ways and easements that have been obscured by misleading signage and private development. As the collective of geographers, architects, environmental artists and historians states, “In a dense and diverse city hungry for public space, the Malibu Public Beaches project elucidates and activates the important public space of the beach … [and] offers an accessible format for navigating the often confusing interface between public and private lands, making these spectacular beaches easier to find, access and enjoy.” The map is available for free download on the Rangers’ website (where you can also find a Spanish-language version).

Armborst, D'Oca, and Theodore are the principals and co-founders of Interboro Partners, a New York City-based architecture, planning and research collective.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine