Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberThe long stretch of a road leading to Chicago’s Plato Learning Academy middle school is unpaved. Sewer lids rest above the torn asphalt. The road softens near the school, which sits, unassuming, among modest brick houses on Chicago’s Far West Side. On a Friday morning in spring, the street was fairly quiet. A few men congregated on the corner, another few chatted on a stoop. Inside the school, its principal, Vanessa Scott-Thompson, redirected an older woman who had mistaken the school for a church soup kitchen next door. Usually, the school tries to keep its doors locked, Scott-Thompson amicably explained.

Two miles west, in neighboring Oak Park, sits a Starbucks. On the same Friday morning, Joseph Quille paid for a coffee, and then handed over a five-dollar bill. This got Quille two red-white-and-blue wristbands, one gripped by a half-inch metal rectangle bearing the word “Indivisible.” A cardboard placard announced that 100 percent of his donation would go “to create and sustain jobs in communities across America.” Though he didn’t know it at the time, Quille was donating his $5 to Plato Learning Academy, to help the charter pay down a loan on the school a few blocks away.

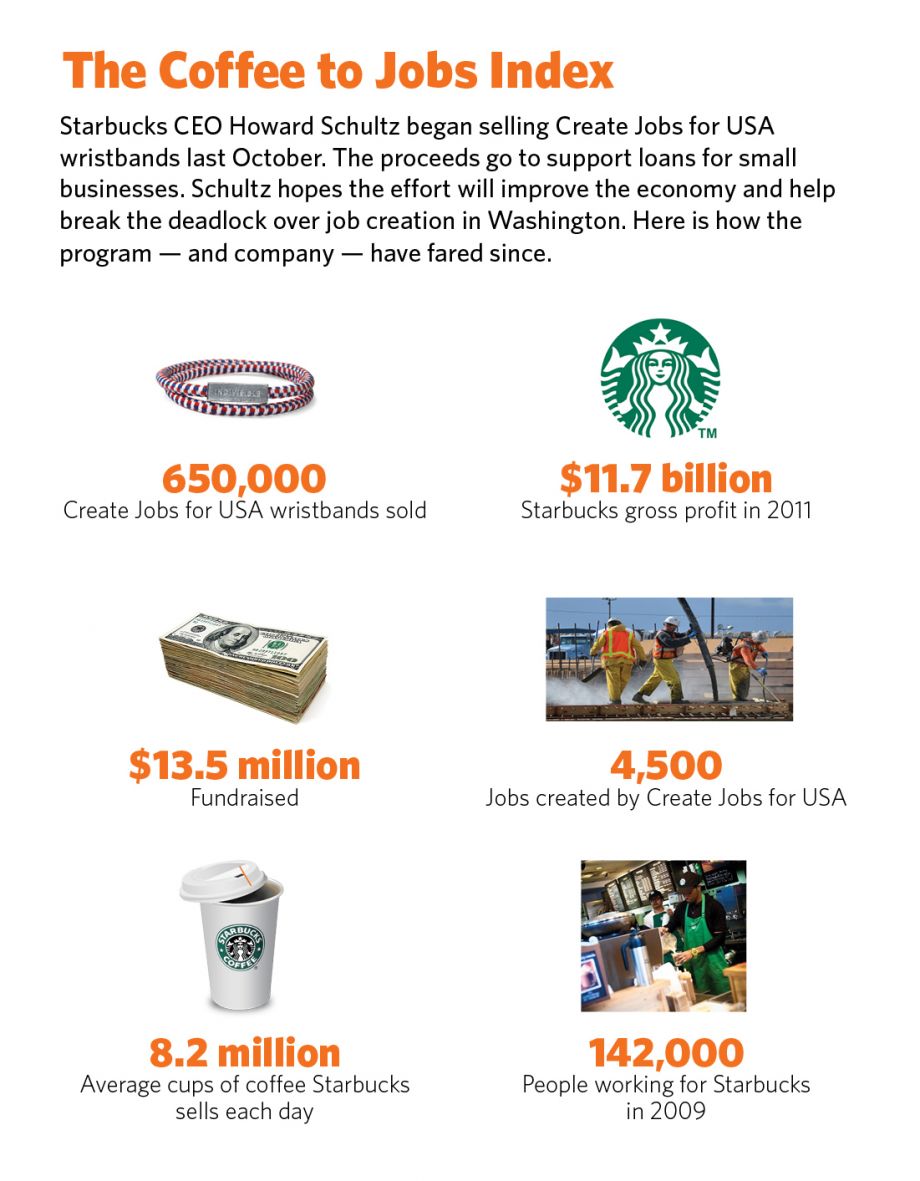

The wristband held by Quille is the official talisman of Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz’s latest attempt to reshape the American marketplace: Create Jobs for USA. Each wristband — 650,000 were distributed as of last count this summer — represents a donation made to Opportunity Finance Network, the nation’s largest consortium of Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) and Starbucks’ partner in the initiative.

CDFIs are U.S. Treasury-certified institutions that offer financial services to communities traditionally overlooked by mainstream lenders. Included among their ranks are small loan funds with several hundred thousand dollars in assets, as well as large depository institutions such as Self Help Credit Union, which has about $1 billion in assets.

When Quille bought his coffee and handed over $5 in Chicago, he contributed to a $13.5 million fund managed by the consortium of CDFIs. About a quarter of the fund came from Starbucks customers like Quille, while the rest came from the Starbucks Foundation and corporate partners. (For context, Starbucks brought in $3.3 billion in total revenue in 13 weeks over the summer.) The money from the fund goes from Opportunity Finance Network to the CDFIs that belong to its umbrella consortium and then, through the CDFIs to non-profits or small businesses approved for a low-interest loan. Plato Learning Academy received its $1 million loan from IFF, a non-profit lender in the Midwest.

So far, Opportunity Finance has given to more than 60 of the smaller banking institutions in 45 states, producing 4,500 jobs, a spokesperson for Starbucks said. Schultz calls the program “Americans helping Americans.” And while Scott-Thompson over at Plato Learning Academy, as well as hundreds of other recipients, can vouch that the program is indeed helping Americans — in her case, educators and school children — that is not its sole effect. With its indirect support of charter schools, the coffee seller has moved into one of the most contentious policy arenas in U.S. cities. And it has illustrated that creating, and sustaining, jobs is never as easy as it sounds.

On August 15, 2011, Howard Schultz penned an angry letter. His audience was Congress and the president, his demands twofold: They needed to create “a transparent, comprehensive, bipartisan debt-and-deficit package,” and they needed to speed up job creation efforts. Until then, the 331st wealthiest person in the country was not going to give another cent in donations.

Schultz’s boycott hits one party particularly hard. According to numbers compiled by the Center for Responsive Politics, Schultz and his wife, Sheri, have donated more than $183,000 to federal campaigns since 1994. The lion’s share, 95 percent, has gone to Democrats.

His assessment of our economic malaise sounds much like that of his party. “The more we stimulate demand and increase the purchasing power of middle-class consumers,” he said last November, “the faster we will recover.” Eight months later, the latest payroll data revealed we are not recovering. Three years after the recession formally ended, nearly 13 million people remain unemployed.

In his letter, Schultz plugged No Labels, a centrist coalition of business and political bigwigs that casts itself as the practical alternative to a Congress paralyzed by partisanship. The Starbucks program pitches itself the same way. Donations are met with larger gifts from the company’s philanthropic arm, which then go to support projects — like an affordable housing development in Baltimore — that are mostly agreeable to people of all political stripes.

Yet no matter how benign the program’s intent, its mission hurtles the man who brought the latte to Middle America smack dab in the middle of the decade’s trickiest political conundrum.

Since the recession struck, community lending has been on the menu of several job creation proposals pushed by economists and advocates. It was just far down on the list, below the main fiscal recommendations bought to Capital Hill — the wider-reaching policies to fund infrastructure projects, restore the housing market, slice the trade deficit and spur public hiring.

But then Congress reached its stalemate, clogging nearly every avenue. “The problem,” explained Dave Johnson, a fellow with Campaign for America’s Future, a liberal group that promotes job creation policies, “is that everything is being blocked.”

Advocates have had to get creative, often scaling down their proposals. James Hairston, an economic policy associate with the Center for American Progress, explained how his group began supporting the CDFI Bond Guarantee, an initiative to extend capital to lenders, in part because it didn’t require significant political action. “If we’re looking for new ways to spur job creation in communities that are underserved,” he said, “we have the infrastructure already.” But he did stress that support for community lending “wasn’t in lieu of a larger package.” Compared to wider fiscal stimulus, the effect of the Starbucks approach is minimal and uncertain. “It’s like a tiny stab in the dark,” said Johnson.

The history of this movement traces back to 1977 with the creation of the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA). Passed by Congress as a result of pressure from community activists in urban neighborhoods long ignored by banks, the act charged CDFIs with the responsibility of meeting the needs of borrowers in low-income or distressed areas, where banks traditionally would not go.

The act had enormous implications for cities. Widespread redlining and discrimination had turned swaths of inner cities into financing deserts, and for several decades CDFIs were one of the only lenders to homebuyers in impoverished communities of color. Until the early 1990s, virtually any affordable mortgage could be traced back to a CDFI.

At that point, private lenders quickly subsumed CDFIs as the primary originators of risky loans in the single-family market. When the housing bubble burst, some critics panned the CRA, with its urban lending requirements, for sparking the crisis. Yet evidence shows that the law, partially dismantled during the George W. Bush years, had virtually no role in the subprime debacle.

Community lenders did, however, maintain a steady presence in the multifamily sector, providing developers with initial acquisition funds that few traditional banks would hand over. And they pushed for the creation of the low-income housing tax credit, the primary subsidy for dense residential development in cities.

“CDFIS are the best-kept secret in American finance,” said Robin Hacke, director of capital formation at Living Cities, a funding collaborative of 22 foundations and philanthropic organizations. Unique to CDFIs is what experts call their “double bottom line,” a mission that strives for both financial growth and social impact. “They are able to balance the need to sustain themselves with the idea that they are not profit-maximizing,” Hacke explained.

Yet overall, CDFIs have not weathered the crisis and its aftermath well. They receive most of their equity from government and private donations, funding sources that have shriveled. In 2009, half of the CDFIs reporting to the Treasury said they felt constrained by insufficient capital. The anemic economy has not helped. Last year, for the first time, CDFIs reported a “charge-off rate” — the amount of unpaid loans written away — exceeding that of traditional banks. If you ask industry observers, however, some say that it’s more than a weak economy hurting these non-profit financial institutions.

“It’s been a tough five, 10 years for CDFIs,” said John Caskey, an economics professor at Swarthmore College, “mainly because they’ve sort of fallen out of fashion.”

Twenty years ago, a brazen presidential candidate first aspired to bring CDFIs into fashion. Bill Clinton pledged to spend $1 billion to create 100 new community lenders, but quickly revised his plan, once in office, to prop up current CDFIs instead. In 1994, Congress created the CDFI Fund.

Fresh out of the gate, it stumbled. As governor of Arkansas, Clinton had established a rapport with a co-founder of Shorebank, a CDFI based in Chicago. In the Fund’s first round, a substantial portion went to Shorebank, earning the investigation and ire of the opposition party. The Economist lamented the program’s start: “the CDFI fund [sic] in its early years was wasteful, politically naive and, at times, incompetent.”

In 2009, Shorebank posted crushing losses of $119 million. They lost another $40 million in 2010 before the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation stepped in. Spencer Bachus, the Republican chair of the House Financial Services Committee, rehashed his critique from a decade before, aimed this time at a Democratic president with deep Chicago ties.

Shorebank is now shorthand for the foibles of community lending. As such, practitioners rush to name the failed bank an outlier. Not long after its collapse, Mark Pinsky, president and CEO of Opportunity Finance Network, wrote, “the end of Shorebank seems to be an exception, not the start of a trend.” The banks’ problems stemmed from their status as a depository institution, competing with financial behemoths in a niche market, housing, that exploded in their face.

To a certain extent, Pisnky is right: Shorebank was an anomaly. Less than 10 percent of the 988 CDFIs certified by the Treasury, as of this May, are banks. A bulk of the institutions is loan funds, while credit unions, at 219, come in at a distant second. The remaining, tiny fragment of lenders is depository holding companies and venture capital funds.

By their very nature, CDFIs deal in risk. They lend in riskier areas, to riskier clients, to riskier markets. With that risk comes loan capital losses much higher than those at traditional banks. “I’ve seen CDFIs take significant losses when they do things that banks would not do,” explained Caskey. “They don’t take big losses if they act just like banks. But then there’s no reason to have them.”

CDFIs are largely unregulated, making comprehensive data on the industry nearly impossible to find. Yet numbers collected by the Treasury suggest that, as the economy continues to stagnate, their reasons to stick around are rising. More than half of the institutions reported a steady uptick in loan originations since the housing crash. Indeed, it may just be that CDFIs are once again in vogue.

The return to fashion is structural in its origin. Prior to crisis, when bank lending was rampant, CDFIs attracted borrowers with the shoddiest credit. Now, with banks reluctant to lend, even squeaky-clean borrowers have to look at such alternative institutions. “We’re actually seeing better qualified candidates than we have before,” said Galen Gondolfi, a senior loan counselor for Justine Peterson, a St. Louis-based lender. “This is the highest demand we’ve seen in our history.”

Pinsky, president and CEO of OFN, watched all of this happen. In 2002, President Bush appointed him to the advisory board of the CDFI Fund, the Federal oversight office housed under the Treasury Department. Pinsky served four years there, learning the industry’s evolving landscape and gaining a national reputation; nearly everyone I spoke with said his or her expertise was easily eclipsed by Pinsky’s.

He credits the cautious, thorough approach learned by CDFIs through their work in high-risk markets as helping them weather the financial storm of the last six years.

“When things went sour in 2007, we were probably better prepared than a lot of folks,” he said in a recent interview. “We make it our business to actually know our borrowers. We have balance sheets that are built to last. We specialize in distressed markets.”

Pinsky sits on the board of Net Impact, a San Francisco-based philanthropic group, along with Ben Packard, the vice president of global responsibility for Starbucks. But according to Hacke, the idea for the OFN program was first floated in a meeting with Adam Bortman, digital officer for the coffee giant. He was ecstatic about the idea, said Hacke. His presence there suggests the partnership, from its onset, was more than the flexing of the company’s social responsibility arm — it extends into its entire brand.

The faces Starbucks would like at the front of Create Jobs for USA belong to Amanda and Josiah Phillips. The Kansas City, Mo. couple is friendly and civically engaged. They are both Army veterans. They have five young boys. And they’re entrepreneurs: Two years ago, they started their own storefront bakery, Glass of Milk Cake Company.

Before it opened, Josiah was stationed in San Antonio, where the couple went through a rough patch; they had three miscarriages in as many years. During a fourth pregnancy, they threw a birthday party for their son, splurging their little cash on a cake. It was a disaster. The cake was so disappointing that it prompted Amanda to make her own. “I can’t do any worse than the bakery can,” she recalled.

They moved back to Kansas City, and Amanda’s time baking began to swell, making cakes for friends, then neighbors and co-workers. “There’s a point,” she said, “when you go, ‘Alright, this is turning into an actual business.’”

They expanded, adding more to the menu, and needed cash to back their projected growth. Naturally, they turned to their commercial banks, but came away empty. “These are our banks,” Amanda said, voicing her frustration. Without a ready cash flow or business background, the Phillips family met the new normal: “We were too big of a gamble for them,” Amanda said.

At a local chamber of commerce meeting, Josiah heard a talk on alternative finance. He flagged down the speaker afterwards, and was eventually connected with Gondolfi’s group, Justine Peterson. One thorough application later, the couple finalized a $15,000 loan to back their expansion.

The application the Phillips submitted to secure their loan involved significant financial disclosure and a deep vetting of their background. Once the loan was made, the fund sent along a CPA to the couple. They talk with Gondolfi about once a week. On the afternoon I called them, they had spoke only hours before. “It’s relationship banking,” said Saurabh Narain, chief executive with the National Community Investment Fund.

“We’re talking about changing the lives of people… not talking about making a loan to the next guy who’s buying a house.”

Justine Peterson primarily works in regions scorched by years of predatory lending, where loans for homes and small businesses poured in before the crash, often with little oversight and hidden variable interest rates. CDFI advocates draw out the distinctions between CDFIs and their for-profit peers adamantly. “Unlike banks or predatory lenders that invest in high-risk communities as just one of many money-making strategies, CDFIs have a granular focus,” said Narain. His organization, for instance, is a private equity trust with a singular charge to finance CDFI banks and credit unions operating in distressed urban communities across the country. Since their founding, in 1996, they’ve lent over $24 million to 37 institutions.

“The good thing about CDFIs,” said Hacke, “is that you can really see what the local needs are.”

While banks took huge losses when their hands-off loans began to default, CDFIs often lose money because they get too involved. Many loans come with “technical assistance” — a broad range of financial and legal aid provided to borrowers.

Some of the quirks of alternative finance surprised Josiah Phillips, who has a master’s degree in business orientation management. But he’s been very pleased with the arrangement. He “dusted off all the school books,” though they didn’t help him much. “The traditional stuff isn’t working for anybody,” he said.

The couple now has two full-time staffers and five part-timers, who they pay $8.25 an hour. They don’t offer benefits, but hope to soon. Two days after their loan closed, they hired two of their new employees.

Starbucks points to this news as clear evidence of their program’s success. Your dollars, dropped in the bin, went straight to making two new jobs.

It’s an elegant, hopeful story. But the reality is much murkier.

On February 27, Starbucks and OFN announced they were expanding Create Jobs for USA after raising $2 million. Earlier that month, approval ratings of Congress reached a new all-time low. A borrower in Maine told Businessweek that Starbucks was “doing something” about the economy.

Several of the Starbucks loans arrived in familiar CDFI terrain: Six urban housing projects; a health center in Buffalo; a service network in rural Oregon. A few others have gone to industries not typically considered job generators — a bookseller in Vermont, a furniture maker in Seattle.

The program has yet to venture down every CDFI avenue. In recent years, community lenders started underwriting grocery stores in poor neighborhoods. The two eatery borrowers — Glass of Milk and a specialty gelato store in Maine — look more like Starbucks itself than any proposed fixes to food deserts.

As of September 3, the program has raised $13.5 million, leveraged into $95 million in loans. By OFN’s count, those loans have created or saved 4,500 jobs. That rate is slightly better than the “conservative” estimates OFN made, at the program’s onset, of one job per $21,000 in loans.

It’s a shaky comparison, but consider the Obama stimulus: The high-end estimate was 3.6 million jobs created or saved, after roughly $831 billion. That’s more than $230,000 spent for one job.

Judged by those numbers, the Starbucks narrative compels. Thousands of small business owners, like the Phillips, are itching to hire but cannot access credit. “To the extent that the net new job creators in the U.S. are small business owners,” explained Hacke, “then lending is what you do.” For the lenders, the extent is clear. Gondolfi put it bluntly: “Small businesses aren’t just partnership. They create jobs.”

But evidence that small businesses create and sustain jobs better than others is flimsy. A throng of new economic research suggests that small businesses aren’t the best engine for employment growth. Start-ups, which plunge into new markets, are. And the most productive job creators are often big businesses.

In the first quarter of 2012, Starbucks opened, on net, 241 new stores.

“Do these things make jobs?” he said. “We really don’t know.”

In a 2003 review of CDFIs, Rutgers professor Julia Sass Rubin and her co-authors pointed to the central problem with small enterprises. “The businesses typically generate few jobs and offer few (if any) benefits to their employees,” they write. “It is unrealistic, therefore, to view micro-enterprise as a significant economic development or anti-poverty tool.”

Yet other analysts and practitioners argue that supporting small, local businesses benefits communities beyond just jobs and benefits. The Phillips, for instance, offer a “heroes discount” — a deal for customers that began with veterans, but now extends to firefighters, nurses and teachers. And the double bottom line lending is integral to this impact. “We’re talking about changing the lives of people,” said Narain. “We’re not talking about making a loan to the next guy who’s buying a house.”

Most CDFIs have a limited focus — a city neighborhood, a single street. Measuring a loan’s ripple effect at this scale is simple. “What’s fair to say,” Rubin noted when reached by phone, “is the jobs that they help create probably otherwise wouldn’t exist.” Without the loans, Amanda’s staffers wouldn’t be working in her bakery and the teachers at Plato Learning Academy wouldn’t be in those classrooms.

Yet the overall economic impact of these loans is less cut-and-dry. “If you care only about very local, narrow jobs, then it’s easier to answer,” Caskey said when asked about the employment question. Once you expand your purview, it gets complicated.

To illustrate his point, he used an example of a bakery, a story that could apply to the Phillips’ business. Missourians only buy a certain amount of cakes. They come to Glass of Milk to buy Amanda’s, most likely, because they taste better. But every cake bought there is one not bought elsewhere. Another Kansas City bakery, struggling from this decline in business, might lay off a few employees.

Caskey insisted he was an advocate of CDFIs, namely for their noble social mission. Yet, on employment, he and other researchers arrive at the same conclusion. “Do these things make jobs?” he said. “We really don’t know.”

Little else demonstrates the slipperiness of job estimates as well as charter schools.

In addition to Plato, the Starbucks program has financed three other charters: A middle school in San Jose, a math and science academy in Seattle, and another in Michigan. In the latter, a $1.1 million loan arrived to pay for construction of the Jalen Rose Leadership Academy, a high school founded and dubbed by the former NBA star and Detroit native.

To understand why a CDFI would back a charter school, you need to unpack its twin precepts. The first is to spur economic development; the second, to be a financing pioneer — to advance into markets whose risk, low returns or newness alone spurn traditional banks. As with housing, CDFIs were the first lenders to waltz into charter schools.

The uncertainty with these borrowers is immense. A school may not see its charter renewed. It could lose other funding, causing missed interest payments. Or it could get embroiled in a scarring cheating scandal.

“Meeting the needs of charter schools and figuring out how to create a market for it,” said Hacke, “is exactly the sort of thing that CDFIs are built for.” For Hacke and Pinsky, charter schools are a natural fit for community facility lending. Poor, minority communities are plagued with failing schools. And charter schools, advocates say, are a primary source for human capital development, although evidence for this claim is among the most disputed in policy research.

They are also prime partners. “Charters,” wrote a Philadelphia reporter in the Wall Street Journal, “were a natural for this type of hand-holding, almost intrusive, lender.” With a corner on the market, CDFIs learned the ins and outs of charter school finance better than anyone. Slowly, as with housing, banks began to get in the game, primarily financing capital expenses.

The recession slowed this trend, but several experts claimed that banks are continuing their involvement. Once thrifts move into an industry, CDFIs usually step aside. For charter schools, they stayed, and the two lenders will often work on the same loan. Banks, Pinsky explained, want the expertise CDFIs have.

But ample bank lending doesn’t spread everywhere. It won’t go to a place like Detroit, where city and state budgets are in peril. “Nobody wanted to give a new school a loan, because we didn’t even have state aid coming in,” said Michelle Ruscitti-Miller, director of the Jalen Rose charter. The school now receives funding from the state, at $7,100 per student. But the public support, she claimed, did not cover the $7 million needed to purchase and renovate their building.

“Non-profits are disproportional job creators and retainers,” Pinsky told me. Charter schools are no exception, he said. “They produce construction jobs. They have secondary effects throughout a neighborhood. They are good job producers.”

But Caskey countered this idea. “No one claims charter schools are creating jobs.” They may spur community development by improving education outcomes, depending on what research you believe, or give a new demographic access to teaching jobs that in the past went to other groups. But new, long-terms jobs do not top the list of their selling points and never have.

Unlike consumers, the number of children in a city is usually fixed. A charter can draw families into a school district if its competitive presence compels public schools to perform better, as proponents claim. But the research on this is unclear. More often than not, the kids walking into charters schools arrive from public schools.

As do the teachers. Jalen Rose has nine teachers, and all but two of them came from public schools. Along with Plato, the schools claimed to offer lower teacher-student ratios than public schools in the district. And they tend to create more specialized positions — Plato has a dean of students and a social worker, whose caseload is far smaller than her public counterparts. “Because charter schools employ teachers, administrators, security personnel, janitors and other staff, loans to these schools certainly have an associated jobs benefits,” a Starbucks spokesperson wrote, in response to this criticism.

Yet there is little evidence that charter schools create education jobs rather than just shift them around. And these charters were issued as the public sector was hemorrhaging employment. In 2011 alone, state and local governments slashed an estimated 99,700 education jobs.

“Lots of people talk about the federal fiscal cliff,” said Pinsky. “The municipal fiscal cliff is going to be much larger.” His fear is that strains on city budgets will incline to insolvency, and he sees his role as plugging the emerging holes. “CDFIs are being asked to compensate for a declining subsidy,” he went on. “But we need to be realistic about the fact that we can’t replace public subsidies. We can just try and mitigate.”

For several reasons, job totals are not the best metric for the industry. “The purpose for CDFI lending is not necessarily job growth across the board,” said Sean Zielenbach, a consultant who worked at the CDFI Fund for several years. “Many of them are concerned with improving conditions in distressed areas.” That’s the rationale behind charter school lending. Even for business lending, jobs aren’t the standard bearer. A desirable loan would make a small business self-sufficient. But they may not hire immediately. Conversely, if a business is “going gangbusters, rapidly hiring,” Zielenbach continued, those jobs may not pay well or be there for long.

A bigger blockade to tackling unemployment than tight lending environments may, in fact, be the target of Schultz’s letter. In it, he petitioned others to join his call for “cooperative and more effective government.”

A staunchly divided, uncooperative Congress has created an uncertain climate — businesses don’t know how, or if, regulations and policies will change. Last fall, researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland tried to capture the impact of this policy uncertainty. In its absence, they estimated that roughly 6 percent of small businesses would hire. According to the National Federation of Independent Business, the data source of the study, there are 5.8 million small businesses across the country. If each of those 6 percent hired just one employee, that would create 348,000 jobs — more than 85 times the Create Jobs for USA totals thus far.

Congress is, thanks largely to one party, now poised to arrive at another debt ceiling standoff, one the Congressional Budget Office suggests would heave us back into a recession.

And yet many economists, on both the left and right, concur that the Federal Reserve could do more to spur job growth than any financial lender — or a functioning Congress.

“We need to be realistic about the fact that we can’t replace public subsidies. We can just try and mitigate.”

Whether the Fed will deploy monetary stimulus is unclear. Until then, it’s fair to credit Starbucks with “doing something” about the economy, more so than policymakers in D.C.

That something, however, is not providing sweeping employment gains. Clearly, for the borrowers and the communities they serve, CDFIs deliver results. Solving the jobs crisis is not one of them.

Such nuance — capturing the impact that some lenders have in some neighborhoods — is hard to sell in a national donation campaign. Job creation is an easier pitch. As Zielenbach put it, “You need a bumper sticker.”

At the tail end of our chat, Amanda Phillips recommended a book: Pour Your Heart Into It, Howard Schultz’s business tome. “Personally, I think some companies are very soulless. It’s just money,” she explained. “And some companies are very much about the heart and believing in what they do. I read the Starbucks book when I was in college, and it was amazing. It was the guiding force, the template for how to run our business.”

The couple hadn’t sought out the program when looking for a loan. But it was a pleasant coincidence. “It was even more exciting to have such a massive company backing us,” she said.

Starbucks’ effort is extraordinarily novel. And it may be a harbinger. In early April, they unveiled five new corporations that had signed on to raise donations, including Banana Republic and Google Offers, the tech giant’s coupon program. Pinsky said they would soon reveal additional corporate partners, but would not name them. He also claimed that several small businesses have donated to the campaign.

It’s a form of crowd-funding, a tactic that cities are increasingly using to finance projects. Yet this effort can leverage the marketing arm of a massive global corporation. “It’s a little bit different when people are getting a latte,” said Debra Schwartz, an investments director with the MacArthur Foundation. Small, steady donations from consumers rarely go to these types of non-profits, and these financial institutions have not tapped into this wide philanthropy before. “This is at a much broader scale than we’ve ever seen,” said Schwartz.

For Pinksy and Opportunity Finance Network, the Starbucks initiative is a trial run. When it reaches its one-year anniversary, OFN will assess the program and, if they have their way, inflate it. On the $50 million they’ve raised, Pinsky was frank. “That’s still a small amount of money,” he said. “We need to be able to do significantly more than that. We need to find a way to make this bigger.”

Expanding the program will not move it any closer to unequivocally creating jobs. And any expansion will rely on corporate benevolence. If the economy further sours, if we’re pushed off the fiscal cliff, the coffee chain could tighten its purse strings.

“Starbucks has a history of being a very socially committed organization,” noted Rubin, when I asked her about the program. “But it’s also just good PR.”

A few CDFI experts I spoke with were skeptical that this philanthropic model could sustain the enterprises. Many have stretched their portfolios beyond the reach of dried-up grant funding, so the program fills a bit of that equity gap. To leave sizable national footprints, lenders need much more capital.

Starbucks has tapped into a brewing discontent with Washington. But the influence they have over the economy, with their wristband campaign, pales in comparison to that wielded by the distrusted D.C. officials.

On June 12, the company unveiled the program’s newest corporate partner, Citibank, and its newest loan recipient, an artisanal manufacturer in East Liverpool, Ohio, a major swing state. Their message was clear: Starbucks in investing in these communities, ravaged by job loss, more than either political party.

On the same day, the company also released the latest campaign merchandise — ceramic mugs, tumblers and bags of whole beans that donors like Quille can buy for the price of giving to OFN. This sent a similarly clear message: Starbucks is still, first and foremost, a coffee company. And their lattes are not cheap. This campaign is about branding and PR, but it’s also an urgent attempt to ensure that people in places like East Liverpool will keep waiting in Starbucks lines.

“It’s not just an altruistic effort,” said Johnson, from the Campaign for America’s Future. “They understand that a booming middle class helps Starbucks,” he continued. “Their growth and sales depends on people having good jobs.”

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Mark Bergen is a journalist formerly from Chicago and now based in Bangalore, India. He writes the Econometro blog for Forbes.com and has covered politics and policy for GOOD, The Atlantic Cities, Tablet Magazine, Religion Dispatches and the Chicago Reader.

Adi Talwar is an award-winning photographer based in New York city. He shoots for various publications, corporate and non-profit clients. He is passionate about photographing people and capturing their emotions.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine