Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

The Washington, D.C. Public Library at Mount Vernon Square was completed in 1903, with funds endowed by industrialist Andrew Carnegie. The first floor of the building is now an Apple Store.

Photo by AdamChandler86/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberThree cups of cinnamon dulce flavored coffee, the Wall Street Journal and CNBC. Barbara VanScoy’s morning routine is mostly what you might expect for someone who manages an investment portfolio. She’s even got a Bloomberg Terminal set up in her home office.

“I’m typically reading a lot of materials from various sources,” says VanScoy. “In fixed income, I’m exploring municipal bonds and mortgage-backed securities so I have to know what’s going on in various markets.”

“Fixed income” is the investor term for treasury bonds, state or local government bonds, corporate bonds or securities backed by mortgages, small business loans or other forms of debt. The underlying borrowers generally pay a fixed amount per month or quarter, which is where the term comes from.

One day in mid-May, VanScoy had some cash in her portfolio that she was looking to move into a fixed-income investment. Like all portfolio managers, she has a certain risk tolerance and an expectation of higher returns for riskier investments. But VanScoy doesn’t work for a Wall Street firm, where she would merely be looking for the highest possible return for the relative level of risk for any investment. She happens to work for the F.B. Heron Foundation.

By federal law, private foundations such as Heron must spend at least five percent of their endowments every year on grants and operations — while the other 95 percent gets invested in stocks, fixed income investments and other assets. The income from those investments is what pays for foundations’ grantmaking and operations.

Across the U.S., around 120,000 private foundations currently hold more than a trillion dollars in their investment portfolios. But foundations have traditionally outsourced their investment portfolio management to professional investment firms — including many Wall Street firms.

In 2019, VanScoy became the first in-house fixed-income portfolio manager for the F.B. Heron Foundation, founded in 1992 with a mission to support low-income communities. Heron was the first, and one of the few, foundations to look at its investment portfolio not just as a way to fund its grants and operations, but as a way to achieve its mission as well. Hiring VanScoy was just one in a series of steps it took to build on that vision for how to invest its endowment.

After scanning the market that day in mid-May, VanScoy found an investment she liked — a secondary issuance that originated from the Michigan Housing Authority. “Secondary” means it’s a purchase from another investor, while primary issuances are purchased from the originator.

“I really like state [municipal bond] housing issues because it’s one of the best ways to really target racial inequality and racial equity through racial wealth and homeownership creation,” VanScoy says. “I looked at a few issuances, saw Michigan, liked the demographics of borrowers, and the performance so far.”

So she wrote up a memo and sent it along with her research to CEO Dana Bezerra for discussion and final approval. Instead of calling some outside firm to request that they purchase the investment on the foundation’s behalf, VanScoy herself made the purchase later that same day.

“The way our portfolio is structured, we are always looking for something that’s deeper in community with our grantees, deeper in mission, coupled with maximizing financial performance,” VanScoy says. “It’s always trying to climb the [mission] ladder.”

Philanthropy has long been a means for the powerful and wealthy to put the lipstick of civic duty on the pigs of inequality and exploitation of people and planet. These ultra-rich benefactors have left indelible marks on cities, both in how they made their money as well as how they gave it away.

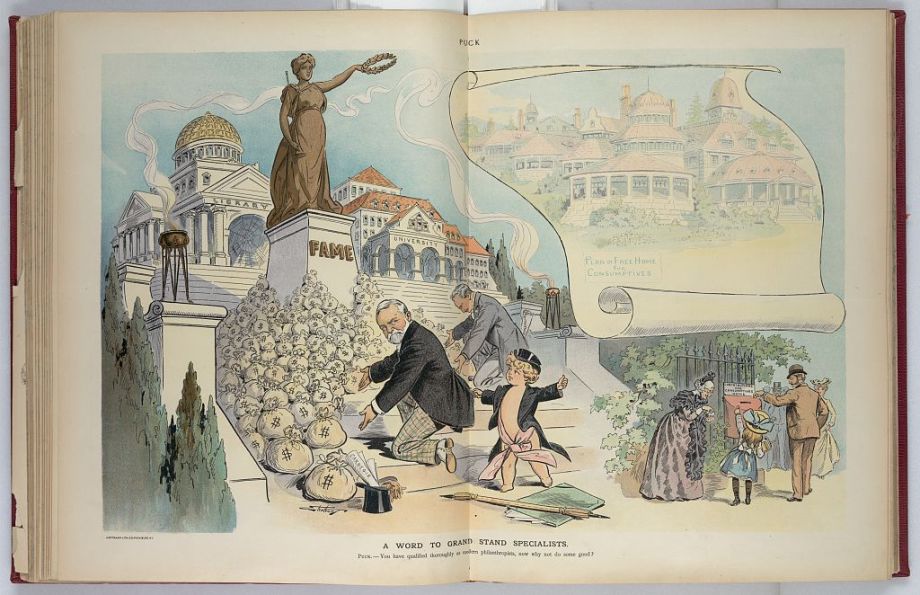

This June 1903 cartoon by artist Samuel D. Ehrhart shows Carnegie leaving bags of money under a statue labeled “Fame,” while others place more modest amounts in a contribution box under a scheme labeled “Plan of Free Home for Consumptives.” The caption reads, “You have qualified thoroughly as modern philanthropists, now why not do some good?”(Credit: Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division)

Most famously, Andrew Carnegie’s steel factories spewed tons of carbon into the skies above Pittsburgh and other newly industrialized cities while his management fought with labor unions at every turn. After selling his steel company to J.P. Morgan for $480 million in 1901 (the equivalent of $15.2 billion in 2021), Carnegie turned around and gave away most of that fortune before he died, building public libraries across the country and funding other well-intentioned endeavors.

Carnegie literally wrote the book on making as much as you can in order to give away as much as you can — well, not a book but a two-part series of magazine articles, called “The Gospel of Wealth.” It called on the rich to use their wealth to improve society. It would inspire future generations of the wealthy to follow in his footsteps, from Henry Ford to multiple generations of Rockefellers.

Today’s Ford Foundation, Rockefeller Foundation and other legacy foundations no longer give away profits accrued mostly from their founders’ original businesses. But they mostly operate on the same basic model. They seek out today the highest possible financial returns from whatever they own in stocks, bonds or other investments in order to fund the largest possible volume of grants tomorrow. Even foundations with living founders, such as the Gates Foundation, operate mostly on that model.

Over time, critics have pointed out the harmful and sometimes hypocritical features of the traditional foundation model. A foundation that grants money to groups pushing for criminal justice reform might also invest in private prisons. Another foundation funding scientific research into more efficient and affordable renewable energy technology might also invest in fossil fuels. A foundation funding tenant organizing on the grants side might also have investments in real estate where property managers routinely harass or evict tenants.

“I think there’s growing momentum among foundations to be looking at using the full 100 percent of their endowments toward their missions,” says Matt Onek, CEO of Mission Investors Exchange, a network of foundations across the country that support “impact investing,” the practice of making investments that seek a measurable social return in addition to their financial return.

“Not all foundations are going to jump right away to 100 percent or commit to 100 percent,” says Onek. “But there’s increasing recognition that the other 95 percent is a critical way to have an impact toward your mission and align with your values.”

In recent years, some critics have been even louder and bolder about even deeper flaws with the basic foundation model. Some say that everything about it, from the process of selecting grantees to their investment strategies, no matter how well-intentioned, perpetuates the white supremacist power structures that created them in the first place.

In his book, “Decolonizing Wealth: Indigenous Wisdom to Heal Divides and Restore Balance,” author Edgar Villanueva writes, “The field of philanthropy is a living anachronism. It is (we are) like a stodgy relative wearing clothes that will never come back in fashion. It is adamant that it knows best, holding tight the purse strings. It is stubborn. It fails to get with the times, frustrating the younger folks…It is (we are) a sleepwalking sector, white zombies spewing the money of dead white people in the name of charity and benevolence.”

A foundation that grants money to groups pushing for criminal justice reform might also invest in private prisons. Another foundation funding scientific research into more efficient and affordable renewable energy technology might also invest in fossil fuels.

Photo by Cam Miller/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Some critics see foundations as just the latest iteration of the much older pattern of despots, aristocrats or other powerful elites believing themselves to be the only ones worthy of shaping the world.

In “Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World,” author Anand Giridharadas writes, “These elites believe and promote the idea that social change should be pursued principally through the free market and voluntary action, not public life and the law and the reform of the systems that people share in common; that it should be supervised by the winners of capitalism and their allies, and not be antagonistic to their needs; and that the biggest beneficiaries of the status quo should play a leading role in the status quo’s reform.”

Heron isn’t alone in taking these critiques seriously and starting to question and depart from the basic foundation model. In recent years, it’s become more commonplace for foundations to screen out investments in fossil fuels or private prisons from their portfolios.

Following some of Heron’s playbook, other private foundations such as the Nathan Cummings Foundation and the Jessie Smith Noyes Foundation have started finding ways to bring the mission and values from their grantmaking side into their investment side. They’re not just screening out harmful investments like fossil fuels, they’re intentionally looking to make investments in companies or projects that directly generate some kind of positive social or environmental benefits in alignment with their grantmaking missions.

Community foundations have also started implementing changes to the way they manage the investments in their portfolios to depart from the basic model. Unlike private foundations, they actually aren’t bound by the 5-percent spending rule, since they continually fundraise from donors every year. The East Bay Community Foundation recently announced that it is moving its $800 million portfolio of investments into mission-aligned investments.

Mission Investors Exchange has gone from a handful of founding members in the late 1990s — including Heron — to more than 250 members today.

“Over the last year, the growing urgency around the interconnected crises of racial inequity, climate change and COVID recovery have only made foundations even more interested in looking at these various options and really digging deep about what else could they be doing out of their endowments specifically,” says Onek.

Heron Foundation has been on this journey since 1996, just four years after it was established through a $150 million gift from an anonymous donor. Its unusual beginnings meant there was no initial “hero” figure with an ego to massage or legacy to protect. It was during a 1996 board meeting when Heron’s leadership realized they were spending more of their time together talking about investments and financial returns than they were talking about fulfilling the actual mission of the organization.

“Our board from those early moments said the traditional foundation business model made no sense,” says Dana Bezerra, CEO of the Heron Foundation. “That was the culture I was hired into.”

By the time Bezerra came to Heron in 2006, the foundation was already in the practice of using some of its 95 percent to make investments that were aligned with its grantmaking mission of supporting low-income communities. Bezerra says she and her colleagues had the whole range of options available to them to support organizations on the ground doing the work — from grants, to investments out of the 95 percent, to something in-between called “program-related investments,” or PRIs.

With a PRI, the foundation can extend a loan at below-market rate of interest to an organization or to a project. The Ford Foundation was the first to start doing PRIs, in the late 1960s, to finance affordable housing projects in New York City. But the IRS allows foundations to count PRIs as part of their annual 5 percent spend requirement, not the 95 percent in their endowments.

Whatever a situation called for, grant or PRI or portfolio investment, Bezerra and her colleagues could recommend the foundation do it. Sometimes it might be a combination of one or more of those tools. “It was a little bit like the world is your oyster, where your north star is positive outcomes in low-income communities,” Bezerra says of her early days at Heron.

But while Heron’s staff had the option to invest the foundation’s endowment in ways that were aligned with its mission, only 40 percent of its endowment had yet been invested in that way by 2006. Bezerra says the reason why was that the staff were only adding mission-aligned investments to the endowment portfolio as they found them — they hadn’t yet examined all of the prior investments in the endowment for their potential connection to negative or positive outcomes for low-income communities.

Bezerra says it wasn’t till the Great Recession and its aftermath that the foundation started examining each and every investment in its portfolio — some 4,000 investments at the time, worth around $250 million. The foundation bought two Bloomberg Terminals for the office and hired short-term consultants to support its research. The priority they set was job creation — it was 2011, the midst of the now-infamous “jobless recovery” period.

As the research team screened those 4,000 investments, they ranked them by job creation metrics. The top performing investment? A private prison.

Bezerra still vividly remembers the meeting they held to discuss the results, in the conference room of Heron’s seventeenth floor offices at 100 Broadway, one block from Wall Street (the organization has since moved).

That discussion eventually led to what Heron now calls its “net contribution” framework for evaluating investments in its portfolio — going beyond just one metric, accounting for a combination of human, natural, civic and financial factors for each investment and understanding the net positive or negative balance of metrics along those four dimensions. Under that rubric, a private prison was definitely a net negative, which called for divestment.

By 2016, Heron had screened each of its investments for positive impact, in so far as it was knowable and would “allow them to sleep at night,” according to Bezerra. Today, as VanScoy scans the market, if she comes across an investment that’s a higher net positive than others in her portfolio, but she needs cash to make that investment, she can sell off lower-ranked investments in the portfolio to get the cash. The Heron Foundation today has an endowment of more than $283 million — of which, $30 million are fixed-income investments that VanScoy manages in-house.

Heron has been in the practice of publicly listing every investment in its portfolio, although their list has not been updated since 2018. Some investments that have made it through Heron’s net contribution rubric would raise some eyebrows — investments in traditional Wall Street firms such as Blackrock or State Street Global Advisors. It’s a constant work in progress.

“Where we are today is is 100 percent impact-screened, where impact is knowable and measurable, and impact that we can live with for now,” says Bezerra.

One of the reasons white supremacy is so persistent is because it’s so thoroughly institutionalized. The inequity is hard-wired into so many organizational rules and decision-making processes, as well as the broader ecosystems that connect institutions to each other. Foundations — including Heron — exhibit some of the most frustrating examples of that.

“Our board from those early moments said the traditional foundation business model made no sense,” says Dana Bezerra, CEO of the Heron Foundation. “That was the culture I was hired into.”

Photo by Wayne Hsieh/CC BY-NC 2.0

The Nathan Cummings Foundation describes itself as being rooted in “the Jewish tradition of social justice,” and “working to create a more just, vibrant, sustainable, and democratic society.” It has taken a very different path from Heron to align its endowment investment strategy with its mission. For one thing, its founder was not anonymous, and he has living descendants who are still active on the foundation’s board. And those descendants have been some of the leading voices to push the foundation in the direction it continues to move today with regard to how its endowment gets invested.

Yet even with the living descendants of Nathan Cummings pushing to change the foundation’s investment strategy, that can’t happen overnight. As with any foundation, it takes four of the organization’s bodies to agree to do it before that journey can begin.

The first “yes” must come from the foundation’s board of trustees. If the people at this level are inclined to maintain the status quo, the journey stops there. According to a survey by BoardSource, a research and support organization for nonprofit boards, 40% of foundation boards are all white, only 15% of foundation board members are people of color, and only 5% of foundation board chairs are people of color. Another analysis of the top 20 largest foundations by the Chronicle of Philanthropy found that their 253 trustees were predominantly Ivy League-educated “coastal elites.” That doesn’t mean to imply trustees with those characteristics are guaranteed to say no when it comes to making changes in how endowments get invested. But it’s valuable context to understand the starting point required of such discussions if a foundation wants to move away from the traditional foundation model.

At Nathan Cummings, the founder’s living descendants still sit on the board, and former board chair Ruth Cummings was one of the leading voices who pushed to move the foundation’s endowment 100 percent to mission-aligned investing. So that decision ended up being an easy yes.

A second “yes” must come from the investment committee, which includes some trustees and, for some foundations, external members whose advice the board values when it comes to setting the investment strategy for the endowment. The one skeptic on the Nathan Cummings Foundation’s Investment Committee just happened to be an external member who chaired the investment committee at the time. The result was a “yes, but…” with a caveat that would initially limit how much of its endowment the foundation would invest in ways that reflected its mission.

The staff, and particularly the CEO, must supply a third “yes.” Given that these voices are typically already focused exclusively on the mission, they’re typically the most willing to agree, and often are leading the discussion to shift foundations’ investment strategies to a more mission orientation.

The board of trustees, investment committee and staff at Nathan Cummings Foundation all said “yes” to a 100-percent mission-aligned investment strategy by November 2017.

But securing the fourth “yes” can be the trickiest of them all. Most foundations outsource the management of their investment portfolios to organizations that specialize in the work, known as “OCIO” groups — an acronym for “outsourced chief investment officer.” The OCIO, sometimes simply called a consultant, doesn’t choose a foundation’s specific investments. They pick which asset management firms will make investments on behalf of a foundation. The Nathan Cummings Foundation needed its OCIO to commit to the 100-percent mission-aligned investment strategy. So far, it has stayed with the OCIO it has worked with since 2017, although they issued an RFP in October 2020 to either renew their OCIO agreement or select a new firm.

The criteria that OCIO groups typically use to select a client’s asset management firms often perpetuate racial disparities in the asset management industry. Asset management firms registered in the U.S. manage investments on behalf of foundations, universities, state and local governments, insurance companies, retirees, corporations and more. As of 2017, less than 1% of the $70 trillion managed by asset management firms in the U.S. are managed by firms led by women or people of color, according to a report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office. Foundations as a group are no exception to that pattern.

But more foundations today are pushing back on their OCIOs to change criteria in how asset management firms are chosen — changes that will not only help to address that racial disparity, but will also widen the path for mission-aligned asset managers.

For example, typical criteria include a firm’s dollar amount of assets under management or the number of years an asset management firm has been in business. Newer firms led by women or people of color may not meet one or both of the necessary minimum thresholds to be selected by an OCIO. But the founders of those firms may have decades of experience managing hundreds of billions in assets for their previous employers — in other words, they have the experience and qualifications required in their backgrounds, just not with the new firms they’ve recently founded. Similarly, newer firms founded to invest money in ways that might align with a foundation’s mission can face the same situations — founders with the requisite experience but firms that fall short of the requisite thresholds.

“Individually, any one of those criteria seems reasonable. But taken in the aggregate those things end up becoming exclusionary,” says Bob Bancroft, vice president of finance at the Nathan Cummings Foundation.

The Nathan Cummings Foundation is one of a growing number of foundations pushing back against typical OCIO criteria, for the sake of racial equity as well as for the sake of finding more asset management firms that are willing and able to prioritize mission-aligned investments, instead of choosing investments that simply maximize financial return.

“I was recruited [to the Nathan Cummings Foundation board] with the goal of coming on to the investment committee and focusing on this transformation,” says Rey Ramsey, who has faced those kinds of racially discriminatory barriers as a Black investment professional. Ramsey joined the foundation’s board in May 2017.

“Too many people still look across the table and they don’t see an investment professional, they see color, they see gender,” Ramsey says. “The implicit bias is still there.”

When the Nathan Cummings Foundation’s trustees made their mission-alignment commitment in 2018, nearly half of the foundation’s portfolio was out of alignment with the mission. By 2020, that number was down to 5 percent. The foundation also says 28 percent of its portfolio is now managed by funds that are majority-owned by women and/or people of color, though only 9 percent of its overall portfolio was with asset managers who applied a racial equity lens to the underlying investment decisions.

Prior to her role at Heron, Barbara VanScoy was one of the few women who, in 1998, co-founded and led a successful asset management firm, Community Capital Management. It’s a mutual fund, like the kind in which you might have some retirement savings invested. Both individuals and institutions can buy shares of the fund — it’s listed as “CRATX” on the NASDAQ stock exchange.

As a fund, Community Capital Management pools funds from investors and turns around to make various investments that specifically benefit low-income households — for example, securities backed by mortgages for first-time homeowners, loans to develop or preserve low-income rental housing, or small business loans in low-income communities.

For 20 years, Heron was actually one of VanScoy’s clients at Community Capital Management. One day back in 2006, VanScoy got a call that most would consider strange, but made perfect sense within the context of Heron’s investment strategy.

Heron had been providing grants to credit counseling organizations, helping households avoid or get out of predatory debt. Many of those grantees started reporting that they were seeing a strange spike in clients coming in with adjustable-rate loans that required little to no documentation of income. Interest rates ballooned after a pre-set introductory period with a lower interest rate, and now clients couldn’t afford to pay back those loans. These were the subprime loans, of course, that helped to tank the economy a few years later .

An executive at Heron called VanScoy and told her what it was hearing from those grantees about their clients — this was before the market started to crash in 2007. She used that information to adjust her investment portfolios. As a result, when the crash eventually happened, the mission-screened portion of Heron’s investment portfolio barely lost any value, while the rest of the portfolio it hadn’t yet screened for mission alignment lost more than a third of its value.

The early warning from Heron’s grantees about predatory practices shielded Heron from losing more money than it might have otherwise during the financial crisis. In subsequent years, Heron started going back to their grantees more frequently to help implement and refine their “net contribution” investment rubric, looking for insights on what characteristics they should look for in an investment, as well as what types of investments to avoid entirely.

Now that VanScoy is at Heron full-time, instead of scheduling a call with a friendly investment manager, Heron’s grantmaking staff can call a colleague — or she can call them, as she has, to get advice on things like the wisdom of investing in an affordable housing project and whether the developer or landlord might be a concern for a community, or whether the small businesses she is supporting through her investments are truly in good standing with the communities around them.

But recently, “what started to be uncomfortable was our motivation to [seek out grantee input on our investments],” Bezerra says. “We were doing it to learn what communities wanted to see us invest in with our endowment, but it started to feel extractive. We needed to find a way to cede power to communities if we really believed that they had the wisdom to make these decisions anyway.”

It’s historically been very easy for trustees or investment committees to oppose more mission-aligned investing because doing so raises the spectre of lower returns. But last year, the Rockefeller Brothers Foundation reported that after divesting its endowment from fossil fuels five years ago, its endowment grew faster than it would have had it kept those fossil fuel investments.

Photo courtesy of the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Out in the rest of the foundation world, these past few years have also witnessed a rise in “participatory” grantmaking. This practice takes different forms, but starts from the premise that foundations don’t have any rights to wield all the power they’ve traditionally wielded to select who gets grants and for how much. As an emerging alternative, foundations are starting to share power, or even completely cede to communities the power to select grantees.

But remember that grantmaking typically only spends 5% of a foundation’s assets. Decisions on how to manage the remaining 95% still reside with foundation boards, investment committees, staff and OCIOs.

Heron’s next step is to begin turning power over to its target communities over everything from making grants to choosing the investments for its endowment. Starting in one community where it happens to have a concentration of grantees, Heron is experimenting with giving that community carte-blanche to grant out or invest a slice of the foundation’s endowment through a community-rooted process of their own design, including their own investment committee.

“We have repositioned our organization as an advisor for when they want advice or implementation assistance,” says Bezerra. “Otherwise they have unfettered access to a portion of our balance sheet.”

The Heron Foundation and Nathan Cummings Foundation represent sizable pots of money, with $280 million and $440 million respectively in their endowments. But even those are just drops in the bucket compared to the Rockefeller Foundation’s $4 billion, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s $9.6 billion or the Ford Foundation’s $12 billion. Biggest of them all is the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, with around $40 billion in invested assets.

Some of those larger foundations, particularly Ford, do get credit for pioneering new tools in the foundation toolbox, such as program-related investments. The Lilly Endowment, with a $10 billion endowment, makes it the country’s third-largest private foundation. Lilly has an annual tradition called “sustainability grants,” in which nonprofits in its hometown Indianapolis region get funding to create their own mini-endowments, whose investment income helps pay for that nonprofit’s standard ongoing operating expenses.

But by and large, the larger foundations lag behind when it comes to considering how to invest the 95 percent they keep invested every year in ways that specifically advance their missions.

“At that scale, it’s hard to move that much money overnight,” says Matt Onek. “But I think you’ll see a continued evolution at the bigger foundations in the years ahead.”

Part of the challenge of convincing more foundation boards and investment committees to shift into more mission-aligned investments is regulatory. IRS rules around foundation endowments have shifted from administration to administration. Under the George W. Bush administration, the agency effectively told foundations they must invest their endowments purely for financial return. It took until 2015 under the Obama Administration to reverse those rules and give foundations more flexibility to consider factors other than financial risk and return when investing their endowments.

Regulatory rules have never posed a prohibitive barrier to Heron Foundation’s work on its endowment. But they are certainly a convenient excuse for investment committees or OCIOs to wield when someone starts asking about doing things differently. They may also be thinking about business or personal relationships they want to protect. The larger the foundation, the more asset management firms it employs, and those firms in turn are figuratively (and sometimes literally) wining and dining OCIOs and foundation investment committees.

“All of those are long-established relationships or partnerships that may take time to unwind or evolve,” Onek says.

A decade ago, large Wall Street firms still saw “impact investing” as a fad, or something that would never go beyond a niche. But now Goldman Sachs, Blackrock, State Street Global Advisors and pretty much every Wall Street asset management firm has some kind of “impact investing” division — in large part to keep the trillion-dollar foundation sector within their client base.

It’s historically been very easy for trustees or investment committees to oppose more mission-aligned investing because doing so raises the spectre of lower returns. But more and more data and examples have emerged that demonstrate that this lackluster spectre is nothing more than that — an illusion. Last year, the Rockefeller Brothers Foundation, representing an arm of the Rockefeller family and its oil wealth, reported that after divesting its endowment from fossil fuels five years ago, its endowment grew faster than it would have had it kept those fossil fuel investments.

Fixing what’s wrong with foundations won’t fix the world. But as Edgar Villanueva argues in “Decolonizing Wealth,” if foundations truly exist to make the world a better place, there are ways they can demonstrate what it looks like to try to fix what’s wrong with the world. And the starting point in understanding what’s wrong with the world is not the lack of affordable housing or lack of access to healthy food or to healthcare. What’s wrong with the world starts with how it extracts from the many and concentrates wealth and power in the hands of a small and relatively homogenous group of people.

“Reparations are due,” Villanueva writes. “Philanthropy, as the sector most ostensibly responsible for healing, could and should lead the way…It’s the most powerful commitment that can be made to decolonizing wealth and healing our country. Reparations are the ultimate way to build power in exploited communities. They are the ultimate way to use money as medicine. The institutions of philanthropy and finance can take a giant leap forward and make a commitment, leading the way for government to finally follow suit.”

This article is part of The Bottom Line, a series exploring scalable solutions for problems related to affordability, inclusive economic growth and access to capital. Click here to subscribe to our Bottom Line newsletter. The Bottom Line is made possible with support from Citi.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine