Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

Ecohybridity members parade across the industrial Canal in the Ninth Ward. (Credit: Ecohybridity)

City zoning that supports fair housing is boring. Very few people want to jump into a casual conversation about the best way to manage blight or reduce verbal street harassment. Unless you’re with friends, it’s next to impossible for a discussion about Confederate monuments or race and policing to become anything but inflammatory. (If you need evidence of that, refer to the comments section below any online article attempting to deal with those topics.) Yet these issues of urban justice can’t be left to trolls, or even politicians, to hash out — not if we want to see progress in our cities. Change will only come as a result of public awareness, dialogue and, ultimately, political pressure.

So, the question becomes a simple one: How do we get people to pay attention?

Over the past several years, activists in cities from Cairo to Oakland to Rio de Janeiro have increasingly found answers in the built environment and the field of design. They have protested inadequate infrastructure by building their own, deployed street art as political missive and reappropriated abandoned homes. All of this can be described as design as protest.

In a sense, design as protest is a matter of branding. It is a means of broadcasting a message and drawing people in. In rare cases, actions like blocking a road or projecting controversial images onto a building, or taking urban wayfinding into a community’s own hands are designed to be ends in themselves. More often, they’re attractive, often jarring, aesthetic interruptions that force the broader public to stop and consider something new. They’re billboards advertising a product you’ve never heard of. They’re movie trailers, inviting you to a feature film that will change the world.

In another sense, when we talk about design as protest, it applies to the unique design of the protest itself. It’s about organizers using the urban landscape as a tool in service of their message. This approach requires a fundamental understanding of history, urban context, and the way cities work to be intentional and effective.

Over the course of the last year, with the rise of Black Lives Matter, the United States has seen countless examples of these interventions — both of organizers adding material to the urban landscape and of groups using its inherent elements as instruments themselves. And while the cityscape is available to anyone as a canvas for transformation and message delivery, those who are intimately familiar with its design, contours and flow are in a unique position to facilitate effective interruptions.

This week, the National Organization of Minority Architects is holding its annual conference in New Orleans. On Wednesday, Next City will join NOMA in hosting a one-day workshop for community organizers, architects, artists and activists dedicated to these ideas. We will be exploring how design and place-based interventions can drive social change. What follows are examples of New Orleans designers and artists doing just this. These precedents aim to serve as an invitation for urban planners, designers and architects to join the conversation and consider with us the use — and misuse — of public space in the service of transformation.

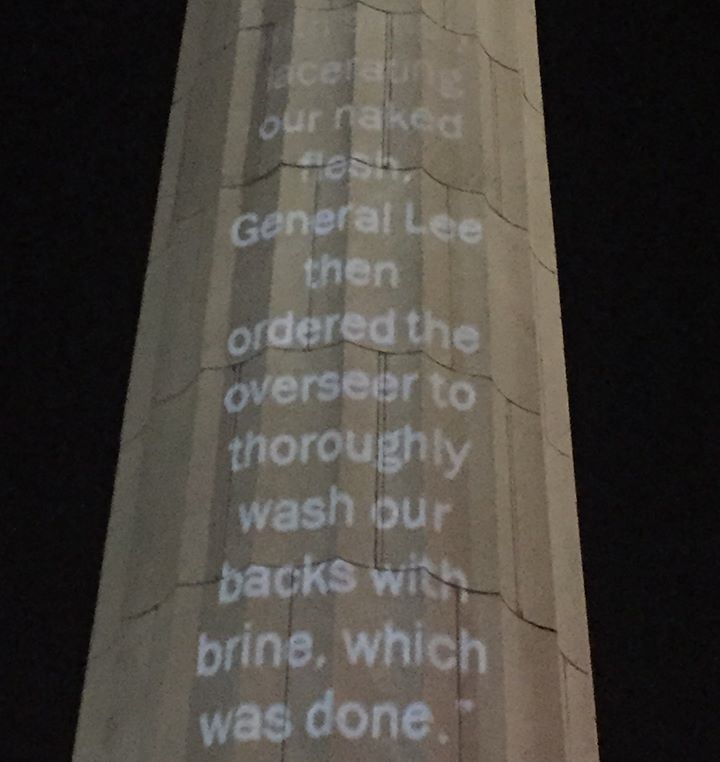

Take Em Down NOLA images projected onto the Robert E. Lee monument in Lee Circle on White Linen Night in New Orleans (Photo by Bryan Lee)

The first Saturday in August marks White Linen Night in New Orleans. A chance for people to peruse the downtown art galleries and sweat on each other in the blazing summer heat, most people expect no more from their evening than free white wine and some decent local art. This past August, however, that rather apolitical tradition was interrupted by a group of artists and activists determined to remove a monument honoring Confederate General Robert E. Lee from the city’s built environment.

Just around the corner from the galleries, a 12-foot statue of Lee sits atop a Doric column, towering above a busy traffic circle.

On White Linen Night, wine-sipping art patrons passing by the circle looked up to find the familiar monument transformed. A scrolling roll of images and text had been projected onto the four-story-high column under the Lee statue. Beginning with a testimony by a former slave of Lee’s, the passage recounted the whippings and harsh treatment he and others received from the General, paired with images of a slave’s back, scarred with lacerations. An excerpt from a letter that the General wrote to his wife, followed. In it, he expresses his belief that blacks are an inferior race to whites. It’s a contested passage; many argue it demonstrates Lee’s overall sentiment that slavery is a necessary evil. But installation designer Jakob Rosenzweig explains why he and his co-organizers at Take Em Down NOLA chose to include it: “He says slavery is a bad thing, and that it’s even worse for whites than it is for the black race.” In his letter, Lee writes that blacks are “immeasurably better here than in Africa, morally, socially and physically” and that his sentiments lie with whites for having to endure the moral struggle of owning slaves.

Take Em Down NOLA is a black-led coalition aimed at removing monuments and changing street, school and park names that memorialize racist and white supremacist figures in U.S. history.

Since the Charleston shootings this summer, New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu has been vocal about removing Confederate and white supremacist monuments around town. But coalition leader Ascribecalledquess? makes certain to point out that this effort preceded the shootings.

“We were doing this way before Mitch Landrieu walked to the table,” says Quess?, who participated in a Confederate flag burning held at the circle before the shootings in South Carolina.

Quess? mentions local activists Leon Waters and Malcolm Suber, whose efforts to change school names and raise the profile of the 1811 slave rebellion in New Orleans extend back for decades.

Rosenzweig says the idea for the White Linen Night installation was inspired by polish artist Krzysztof Wodiczko, known for his interrogative designs across the world. Among many others, Wodiczko projected an image of Ronald Reagan’s hand against the AT&T Long Lines Building in New York the night before the presidential election in 1984, said to highlight the fraught relationship between politics and corporations.

The final of the scrolling images against the Lee column was a quote from Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow, nestled between two photographs. The first was of the sleeping quarters on a slave ship; the second was uncannily similar, and pictured the beds in a prison cell.

“We have not ended racial caste in America,” Alexander wrote. “We have merely redesigned it.”

AScribecalledquess? says it was important to include images in the projection that tied the hatred of Lee and other Confederate figures to our society today.

“The irony is that despite how obvious, there’s a lot of complacency,” he said.

“It’s rooted in ‘this is just the way it is, why bother with that?’ From people in our communities, sometimes our own demographic. But if you’re going to accept that, it’s no wonder you’re going to accept everything else, unemployment, discrimination, incarceration.”

Freddy “Hollywood” Delahoussaye performs during a Blights Out porch crawl. (Photo by Scott McCrossen)

In the decade since Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans neighborhoods have attracted plenty of interest from private developers and city officials eager to leave their mark on the changing city with big, bold redevelopment projects. In such a climate, says Imani Jacqueline Brown, an artist and organizer of the Blights Out project, blighted homes are perceived as a nuisance, an obstacle to find the quickest route around by demolition or renovation. But Brown says that’s a dangerous approach, and that it’s important to treat vacant homes as less of an eyesore and more of a story.

“We’re not looking at blighted houses as voids, but as vessels,” says Brown. “They tell a collective history.”

To highlight the narratives embedded in neighborhoods, last fall, Blights Out organized a porch crawl among vacant homes in New Orleans’ Sixth Ward. Residents and newcomers alike paraded to the tune of a second line brass band between the stops. At each home, spoken word artists and actors performed interactive pieces inspired by and in dialogue with the homes.

“We call this idea performing architecture,” says Brown. “It’s listening to what the house has to say.”

Brown says it’s no accident that Blights Out chose to use the second line as a vehicle to bring people together in celebration around critical neighborhood issues. She says it’s always been the unique role of mutual aid societies to support working-class neighborhoods of color. There’s no reason they shouldn’t do so now.

“The separation between culture and civics is false,” Brown says. “We’re bringing them together to bring them back to where they naturally exist and nest.”

Blights Out is using events like the porch crawl to engage neighbors — newcomers and longtime residents alike — and begin a dialogue about blight, but that is only the beginning. Brown says the group plans to buy an abandoned property (the ownership of which will rest in a community land trust) and transform it into a neighborhood center that will help people understand the city’s land acquisition and blight mitigation processes and make them more transparent. She says with the help of the Greater New Orleans Fair Housing Action Center, they recognized there was a void for homeowners.

“Resources are scattered,” she says. “There’s no central body to consolidate them.”

Brown says she knows that the porch crawls and interventions won’t do the work on their own.

“It would be naive of us to say that by doing some artistic gestures we can change politics,” she says. “But the campaigns and direct interventions operate in concentric circles.” And in New Orleans, using music, celebration and performance as a vehicle to facilitate community and change is no foreign concept.

It’s a familiar irony: Newcomers or investors find a city to be culturally unique. They work to develop it and increase its value. In turn, they oppose manifestations of the very culture they fell in love with in order to protect that newly established value. People refurbish homes in funky neighborhoods with a rich history of live music like Treme, and later complain about live music in the very bars where jazz was born and music has been played into the night for decades.

At least, that’s the irony that the Music and Culture Coalition of New Orleans (MaCCNO) sees as a glaring problem.

The closest thing to a functioning musicians’ union the city has, MaCCNO was born out of long-term debates over the city’s outdated noise ordinance. Coalition organizers say the current ordinance — on the books for more than 50 years — is unforgiving to venues that want to host live music. The conversation around revision started happening four or five years ago, but then just before Christmas 2013, unbeknownst to the greater public, a group of neighbors from the French Quarter aimed to sneak what MaCCNO organizers say would have been an unreasonably strict and prohibitive ordinance through the City Council. In January, the City Council was set to hold a public hearing about a slightly modified version of the same ordinance that was passed the month before. And that’s when MaCCNO put out the call.

“We heard about it and so we were able to launch a protest,” says MaCCNO organizer Ethan Ellestad, “which ultimately lead to that ordinance being withdrawn because they realized there was such a massive backlash.”

The Council got spooked; they withdrew the ordinance before the hearing ever happened. But musicians from MaCCNO knew this wouldn’t be the end of it, so they decided to go ahead with a protest. Organizers told everyone with a portable instrument to bring it to Duncan Plaza, directly across from City Hall for a community rally. MaCCNO spokesperson Hannah Kreiger-Benson says the idea was to “celebrate by playing the things we’re here to nurture and support and protect.”

The rally turned into more than a celebration. Led by trumpet player Glen David Andrews, protesters stormed the foyer of City Hall and made their way through the corridors and into the council chamber, blasting horns and beating drums.

“Music and culture get framed in decision-making conversations as a nuisance, as something to be curbed,” says Kreiger-Benson. “It was a moment of occupying and creating a space. That’s exactly what New Orleans cultural practices do, they create a community space. When you have council members second-lining down the hall, that’s kind of the point.”

The New Orleans City Council has yet to adopt a new noise ordinance, but this past spring, they voted on new zoning laws that would make it easier on venues hosting live music. Kreiger-Benson says that by taking over City Hall with music, MaCCNO made their message loud and clear. “It was certainly a reminder of what we have to protect.”

The 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina was a confusing milestone for a lot of Gulf Coast residents. Faced with reductive, redundant and exploitative newspaper articles and their own questions about what to memorialize and what to move past, many residents expressed that they just wished it would be over so they could go on with their normal lives.

But Kai Barrow saw the anniversary as an opportunity. For over a decade she had been working on and conceptualizing a project called Gallery of the Streets. It had all been framed within the idea of thinking about increasing visual aptitude around visual art in black communities.

“We are incredibly visual people,” says Barrow. “Everything about how people live in our communities. Black women especially, how we move, adorn ourselves, everything we’re engaging in virtually is an artistic expression.” She was particularly interested in how these ideas related to geography. Both physical geography and questions of place and displacement, but also what she calls interior geography or “where our imaginations are located.”

Barrow saw the Katrina anniversary as a way to explore those concepts in the face of deep tragedy and community transformation.

“What does disaster capitalism look like on black women’s bodies?” she wanted to know.

To find out, she gathered a group of roughly 15 black feminists who realized a five movement black opera called Ecohybridity throughout the weekend of August 29, 2015. Some movements were in traditional performance spaces, while others commented on particular events or dynamics in the urban landscape by being performed in site-specific locations.

On the morning of August 29th, Ecohybridity performed a dance piece at the site where the levees broke 10 years prior in the Lower Ninth Ward. From there, they marched over the Industrial Canal as a part of an enormous second line along St. Claude Avenue in the Upper Ninth Ward. Dancing in front of and behind a homemade house on wheels, labeled with the phrase “housing is a human right,” Ecohybridity made a stop when the parade passed the St. Roch Market. A historic public market recently redeveloped into a high-end food hall, St. Roch Market has come under criticism for being an emblem of the gentrification taking place in the neighborhoods along St. Claude Avenue.

That day, the group entered the market and performed a vignette, in which they lamented the loss of community in the neighborhood. They ended their performance with a line that remembered back “when this used to be a fish market.” As they turned to leave, one of the members pulled out a raw fish, slammed it on the blinding white tile of the market floor, and left it behind.

Barrow says the intended impact of actions like these is to communicate to other people the possibility of action.

“These are everyday people who are responding. It communicates that there’s possibility. Anyone can do this. You don’t have to be a professional activist. This is about people saying I’ve had enough.” Barrow gives Rosa Parks as an example.

“That appeared to be a random action. It wasn’t,” she says. “But the story that was told, made it seem like anyone could just do that.”

A dance piece about a violent marriage is performed on a Central City street. (Credit: Bound Entertainment)

Central City is a neighborhood that has endured high rates of violent crime in recent decades. Laura Stein and other organizers from Dancing Grounds, a dance studio in New Orleans’ Ninth Ward, were working on site-specific dance pieces that focused on themes of overcoming violence. So, they organized a dance festival that brought site-specific dance pieces together with social justice organizations and nonprofits on O.C. Haley Boulevard, a re-emerging commercial corridor in Central City.

“In general, site-specific performances make you think about spaces differently,” she says. “Normally you just think, ‘oh, there’s that empty lot.’ But the next time you walk by, you think of the dance performance.”

The challenge, though, says Stein is that the pieces came first.

“Dancing Grounds and all of our choreographers are not centrally involved in these issues, so the question is, how do we engage with people who are already doing this work? How do we present it in a way that’s useful to them?”

It seemed difficult for the festival in its current form to answer these questions. So Stein and her group have decided to shift their focus for next year to youth at a charter school in their neighborhood. Middle- and high-schoolers across the city will be trained in basic tools of community organizing and dance and create site-specific performances that occupy the school building.

Stein says she’s excited that this will be a process generated entirely by the people who the issues are affecting.

“We hope that it brings, first of all, just an element of joy into a school building — that it also creates a situation where students associate the buildings as a space where they have agency and the ability to organize.”

Stein says that she and her collaborators can think of a lot of issues affecting youth in charter schools.

“But we wanted to ask, ‘what are your biggest concerns right now, and how can we organize what that is and convey it through performance and think about a collective action?’”

The student performances will be free and open to the public, and take place inside the school building in February 2016. Stein says she’s excited to see the way the students will express their concerns through dance.

“Maybe they’re concerned about a way they’re entering a building, or a vending machine with certain types of chocolate bars. Who are we to say?”

Hollaback! New Orleans wheatpasted these striking posters on walls and buildings in neighorhoods where residents complained of street harassment. (Photo by Vanessa Smith Torres/Hollaback! New Orleans)

“My Outfit Is Not An Invitation.”

“Women Are Not Outside for Your Entertainment.”

“Men Do Not Own the Street.”

These are the phrases that come along with the poster-sized, hand-drawn portraits of women that Tatyana Fazlalizadeh makes as a part of Stop Telling Women to Smile, a global initiative to end street harassment.

Vanessa Smith-Torres chairs the New Orleans chapter of Hollaback, another anti-harassment effort. She got her hands on five of Fazlalizadeh’s posters, and brought together a group of women to wheatpaste the images in public on already graffitied places around New Orleans.

Smith-Torres remembers the comments her group received as they were applying the posters throughout the city: “A couple people said, ‘Oh that’s not really a problem here.’ Of course, those people were men.”

Hollaback is a global initiative that gives women and LGBTQ people the chance to tell and map their stories of street harassment in an online forum, creating a virtual space that can empower women as they move through a real city.

Debjani Roy is the deputy director at Hollaback headquarters in New York. She says that while it’s incredibly important to create space to share stories among victims of harassment online, it’s important to expose a larger public to the issues of street harassment that victims experience every day.

Smith-Torres agrees. She says she doesn’t want to just create an echo chamber of people who are familiar with the problem.

“You need people who are outside of that in order to really make change,” she says. “If it’s in public space, you can’t miss it. Someone who isn’t already part of the experience tangentially will be forced to confront it.”

It is admittedly hard to measure the impact of these initiatives, but both Smith-Torres and Roy say that they can tell they’re having an effect from public reaction as they’re creating the interruptions.

“People ask a lot of questions,” says Roy, who has created chalk-walks that express similar phrases as STWTS posters. “We often get, ‘You really experience this?’”

Chalk-walks and posters have inspired Hollaback to think big about how public design can work to prevent to end harassment. They’re looking to design research based in Stockholm that found certain curvatures in spaces like tunnels and corridors make people less likely to lurk there. They’re working with Hunter College to start thinking about ways that public spaces can be designed to reduce the risk of harassment.

“We gathered a bunch of community members to see if a location with a high level of harassment might improve if we increase the lighting, reduce the shrubs, put more security guards, etc.,” she says. In its early stages, Roy says she’s excited about the potential for the partnership.

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Nina Feldman is an independent journalist focused on audio production. She worked as a regular contributor to NPR member station WWNO in New Orleans and as editor at American Routes. Her work has also appeared on Marketplace, Morning Edition and PRI's The World.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine