Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

AP Photo/Elaine Thompson

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

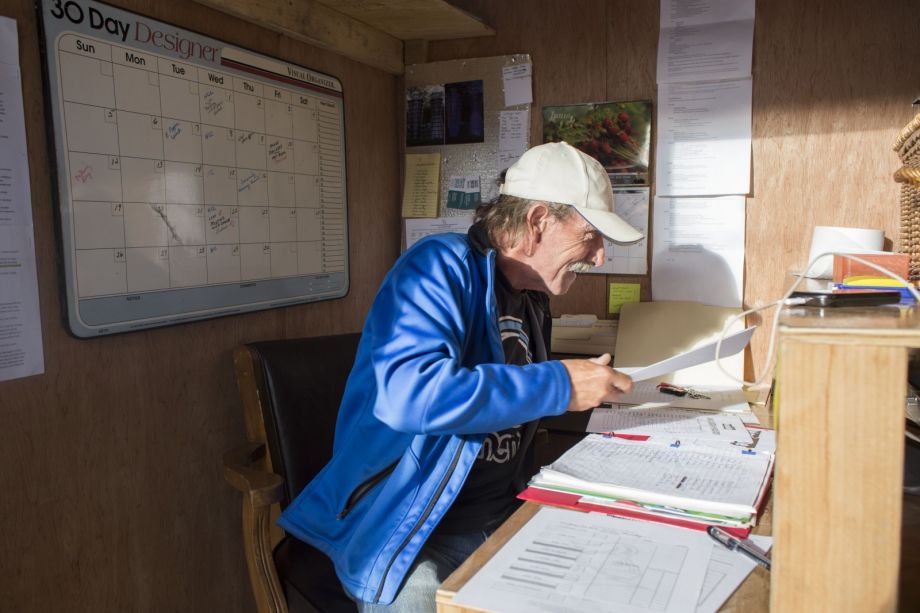

Become A MemberEven though he’s considered unsheltered, literally homeless, Charlie Johnson isn’t ready to move inside.

He lives in a tent, in a row of tents, a procession of polyester and tarp, side by side by side. Across from his door is another row, and behind them another, six rows, 31 tents in all. The kitchen tent is stocked with a bin of potatoes and a locker full of donated bread. A solar panel on the roof powers a toaster; there are two grills on a little deck outside. Unlike the parks where Johnson’s shoes and backpack were stolen while he crashed between shelter stays, at Tent City 5 campers run 24/7 security shifts. Johnson’s tent is his own, day in, day out, unlike at the emergency shelters, where he had to leave early each morning and return each night, toting all of his belongings during the day.

TC5 is quiet too, tucked into a mixed commercial and light industrial zone, just off a main artery in the north Seattle neighborhood of Interbay, between a supermarket and the railroad tracks, on a lot owned by Seattle Light and Power. Rows of single-family houses are visible on the hill blocks away; a “Now Leasing” banner is unfurled from the roof of a brand-new apartment complex one street south. Johnson, 48, sometimes takes his laptop to a nearby Starbucks to read the news, when he isn’t busy dealing with camp paperwork or resolving campers’ concerns. He arrived while TC5 was going up in December, and helped build most of the low wooden platforms that keep the camp’s 31 tents elevated off the sodden ground. Since then, he’s been almost continually part of the camp’s elected leadership, helping to mediate conflicts, intake new residents, enforce the drug and alcohol ban, ensure residents are fulfilling their weekly security shift obligations and, only when absolutely necessary, bar people for breaking the rules.

Until last summer, Johnson — bespectacled and tall, like an earnest high school teacher — had never been unhoused. He had his own place up in Homer, Alaska, and a job he found fulfilling, coaching youth hockey. When his addictions to alcohol and Xanax led to a breakdown and several rounds of treatment, he was too ashamed to return to Alaska. After getting kicked out of a sober house in Seattle, he found himself in the park, then the shelter, then the camp. It’s been a disorienting experience, but Johnson says TC5 is the transition zone he’s needed to return a modicum of stability to his life. He’s on a waiting list for housing, but right now, he can’t imagine moving in. “I’m just shell-shocked still,” he says, “so I’m just trying to do the best that I can right here.”

Johnson is one of about 130 people living out an experiment in urban homelessness policy. Tent City 5 is one of five encampments sanctioned by the city of Seattle and one of three (of those five) funded directly by the city as a means of addressing its homelessness crisis, at least temporarily.

About 50 people stay at Othello Village at any given time, in a mixture of tents and tiny houses. Right now, about nine of those residents are children.

With a population of just over 2 million and 10,000 of them lacking permanent shelter, the county that encompasses Seattle has more homeless residents than any other major metropolitan region in the country other than Los Angeles and New York, according to the federal government. At the last point-in-time count in January, 2,942 people were sleeping outside during the rainiest winter on record in a famously rainy city, 4,505 in King County as a whole.

In a city with a tighter than tight housing market, a city feeling the squeeze of explosive population growth, where residents have strongly resisted upzoning to create further density, developing enough affordable housing for everyone will take years. In the meantime, as recently as May, 400 people were sleeping beneath a stretch of Interstate 5 known as the Jungle. As many as a thousand people are sleeping in their vehicles.

And about 200 people, including Charlie Johnson, are sleeping in tents and tiny houses in secure, self-managed communities in the city-funded camps and in roaming tent cities hosted by churches and private entities. Another 38 people are living in their RVs in city-sanctioned safe zones and safe lots, without fear of being towed.

Tents and tiny houses that resemble garden sheds more than anything you’d see in Dwell are not housing, of course. Seattle Human Services still counts camp residents as homeless. But compared to emergency shelters, the camps provide a higher level of flexibility and self-determination, residents and advocates say. Because there are fewer rules and restrictions — they allow people to remain in couples, bring their pets, store their belongings during the day and come and go as they please — supporters say the authorized encampments create fewer barriers to transitioning into permanent housing and finding work. “It gives you the chance to focus on the real issue behind the homelessness, rather than focusing on where will my next meal come from, what will I do for the next seven hours before I can rest my head again,” says J.R., a camper at a city-funded site.

Meanwhile, detractors counter that the temporary encampments distract from developing long-term solutions and, though better than the sidewalk, are still inhumane. For the city, which declared a state of emergency over homelessness last fall, there are no easy answers. In August, Seattle Mayor Ed Murray hired Barbara Poppe, the former head of the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness as a consultant to help the city manage the growing crisis. In February, she angered supporters — and many colleagues working on the issue — when she told the Seattle Times that she believes encampments sap the resources and political will that could otherwise go toward long-term investments in housing.

“I find it horrifying you have children living in encampments and that is somehow acceptable to this community,” she said. “It’s just unconscionable to me this is a choice that’s been made here. That said, I understand there’s great pressure to have a short-term solution. But I don’t happen to think these encampments are the best solution.”

Poppe’s criticism was poorly received by homeless individuals and advocates, but consistent with her larger critique of Seattle’s overall homelessness response: The system is too complex, too inconsistent and too opaque. Far from a comprehensive response, the encampments and RV sites at times seem to occupy a space as liminal as their residents. The sanctioned RV areas are temporary, some permitted on a month-to-month basis. Each of the three encampments can stay in their sites for at least one year with extension possibilities.

Seattle has played host to sanctioned and unsanctioned homeless encampments on private property, self-governed by their residents, for decades. Tent City 5, Othello Village and Nickelsville Ballard represent the first time the city has dedicated funding and land to establish them, with the understanding that the goal of the temporary camps is to ultimately transition all residents into permanent housing.

A mural at Othello Village decorates the dining area.

The approach has critics other than Poppe. Across the country, policymakers are moving away from a transitional housing model that seeks to provide homeless people with temporary residence and supportive services like behavioral healthcare and job training in order to become “ready” before being permanently housed. The pendulum is swinging toward Housing First, a model that aims to give people permanent housing first, and address the causes that led to their homelessness second. Given that transitional housing programs cost dramatically more without providing measurably better outcomes, the move toward Housing First has been widely hailed as a step closer to resolving a deep social problem that has vexed communities for generations.

“I think after decades of experience what we’ve learned through research is that [transitional housing] doesn’t work,” says Mary Cunningham, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute. “In fact people are ready for housing. They are ready for housing right from the street to an apartment.” Once they’re there, they can be offered stabilizing life services like behavioral healthcare.

Seattle has embraced Housing First, and boasts several innovative and successful models. But given the scope of the need and the time it would take to build enough permanent housing, residents and advocates are saying there is still a need for provisional shelter, for options that fall somewhere between emergency shelter and permanent housing. We might call it “transitional shelter.” (The city calls the new camps “transitional encampments.”) More flexible than transitional housing, safer than the streets, cheaper than your average subsidized or market-rate apartment.

In other cities, most notably San Francisco, that need is being met by low-barrier indoor shelters. And in cities like Eugene, Oregon, and Austin, Texas, encampments have been established not only as emergency shelter but also as more traditional transitional housing, and, even in some cases, permanent housing.

For Charlie Johnson, the Seattle-sanctioned camps are a hypothesis waiting to be proven. He feels they provide a valuable intermediary between a traumatic and uncertain life on the streets, and a return to more traditional housing modes. But on the other hand, he doesn’t feel like the city or the county are taking ownership over what they’ve created, or providing the kind of services the camps would need to succeed. In the long term, he’s undecided. “But in the short term I adamantly defend this model as 100 percent needed and viable and so far proving out,” he says. “Whether these ultimately turned into cool little shelters with solar panels and more structure and it is just a part of the American landscape, maybe that is true. We are going to have so many homeless people for a long, long time. It’s not going away.”

Close to 40 people are packed into the kitchen tent at Othello Village. Rain is beating down on the canvas of the tent and a light rail is slushing past, nearly drowning out the conversation at hand.

Damp banners on Martin Luther King Jr. Way, Othello’s main drag, proclaim the neighborhood’s slogan, “Hello, Othello,” in a riot of languages: Samoan, Maori, Somali, Punjabi. Othello Village campers have arrived here from Ethiopia, from Alaska, from Houston. They have been evicted from their apartments, have lost houses in divorce, are coming from an emergency shelter, have been living in tent cities for years. A toddler in a stroller glows by the light of his mother’s cell phone, cooing at his game and crying when shushed. On this Tuesday night in April, everyone else just looks tired.

Lyle Jones, current head of external affairs, puts a proposal up to vote. Should the camp host a casual conversation with the local police department? A man shredding a piece of paper between his fingers responds without looking up. “If they see us as human, they’ll treat us better,” he says. A murmur of agreement travels the room. It passes, with no dissent.

Othello Village, like the other camps, is self-governed by its residents. Right now there are 49 of them, including nine children, living in a combination of tents and brightly painted tiny houses. Though campers vote on the four main leadership positions every week, J.R. has been re-elected bookkeeper for months. Since arriving shortly after the camp opened in March, newly 60 and homeless for the first time, he’s become an adamant defender of the encampment model. He calls it a “stepping-stone” out of shelter or the streets. “You’re taking baby steps,” he says.

As bookkeeper, he intakes new campers. When someone arrives looking for a place to stay, J.R. hands them a copy of the rules: no illegal substances of any kind on site, no weapons, no abusive language, no open flames. He checks their name against the King County sex offender registry and the list of people permanently barred from other tent cities. If they clear those hurdles, they’re given an available tent for the night.

In the morning, a case manager from the nonprofit Low Income Housing Institute (LIHI) will walk the new camper through the homeless management information system intake. LIHI (pronounced “lee-high”) has a contract with the city to collect that data, oversee the provision of services like sanitation for which the city is paying, and provide case management to campers who want it. Othello Village is also the only city-funded encampment not on city land. Instead, it’s been built on a LIHI property that currently hosts a small apartment complex on one corner, slated for demolition when LIHI develops the lot into affordable housing a few years down the line.

A tiny house in Othello Village fits two cots.

The sanctioned encampments’ management structure, while it sounds complicated, runs smoothly, most of the time. Each camp is self-governed internally, and organized under the umbrella of one of two nonprofits: Nickelsville or SHARE, with LIHI providing support services. Largely self-organized by unhoused people themselves, both SHARE and Nickelsville run other encampments on church and private property elsewhere in Seattle and have been doing so for a combined 26 years. (SHARE convened its first tent city in 1990, and Nickelsville in 2008, but the two organizations overlap leadership and frequently work together.) When the city passed an ordinance in March 2015 to create three new encampments and direct $300,000 to serve them, nonprofits put out a bid to run them. SHARE got TC5, Nickelsville got Othello and Ballard. They were the only organizations to respond to the city’s request for proposal.

Before that vote, tent cities could be permitted anywhere in the city, but only for a maximum of six months before they had to move elsewhere. While the city-funded camps are intended to be a stepping-stone toward housing, Nickelsville and SHARE’s other camps have traditionally seen themselves more as a survival mechanism, a frontline against the unnecessary deaths of homeless people on the streets — in King County, 67 fatalities were recorded in 2015, 13 already this year.

Sharon Lee, executive director of LIHI, says those deaths can be traced back to the city’s decision over the past decade to focus on permanent housing without expanding emergency shelter capacity, even as the rate of unsheltered homelessness continued to rise. Lee disagrees with those who say that encampments distract from investing in long-term solutions. “Encampments help save lives immediately,” she says. “It keeps people safe immediately. It’s not like you need to wait four years for a building to be built.”

For many, the alternatives are the streets, the emergency shelters or illegal encampments, like the notorious Jungle beneath I-5. After two people were killed there this winter, state and city officials have been working on a plan to clear the Jungle and offer its former residents social services. But even there, some residents and some council members have said the city should offer garbage collection, portable toilets and needle collection instead of displacement. Since outreach began in May, many have left the Jungle voluntarily or thanks to a connection with services. About 100 people remain there today, down from around 400 in January. In that time, the city says that 64 people have accepted housing, shelter, services and/or relocation assistance. But broken down by type of intervention, only three people accepted transitional or rapid re-housing (a form of Housing First). Twenty-one entered recovery programs, which provide housing. The largest number by far, 44 people, received “relocation assistance” to move into “authorized or other unauthorized encampments.” A federal task force has discouraged cities from breaking up illegal encampments, saying that doing so only makes it harder for people to move into permanent housing. In one case, the Department of Justice ruled that it’s unconstitutional to criminalize sleeping on the street if there’s nowhere else for that person to go.

Right now in Seattle, there’s not enough permanent housing, or enough shelter beds. Even if there were enough of the latter, many campers told me they wouldn’t want to go. Traditional emergency shelters often run people “like rats through a maze,” says Tim Harris, founder and editor of Seattle’s street newspaper Real Change. When shelters require people to vie for a bed every night and kick them out to roam the streets every morning, “we’re not thinking about how to make this work for them, we’re thinking of how they should fold into what the system wants of them, and that’s backwards,” he says. One Othello Village resident told me of friends who have lugged all their belongings to job interviews, for lack of a safe place to store them. “They don’t get the job,” she says dryly.

Campers often tout that encampments, by contrast, focus more on dignity and self-determination. Particularly for residents who are distrustful of the city, county and other homeless service providers — “poverty pimps,” one camper called them — self-governance is the camp’s primary attraction. “That’s what’s missing from the system,” says Harris. “There are not many places where homeless people get to be adults and run their own lives.”

In addition to voting in their own elected leadership, campers are required to fulfill a certain number of security shifts a week, for a total of 9 to 15 hours. Those who work full-time, as many campers do, sometimes pay unemployed residents a small fee to cover. Campers are also required to fulfill one “participation credit” per month, anything from attending services at a partnering church to advocating for the camps at a city council meeting. Failing to do so could result in a multiday bar, a policy the city officially takes issue with. But for the most part, the city has stayed out of the day-to-day operations of the camps it funds.

Shannon Smith shares a tiny house in Othello Village with her 12-year-old son and their two dogs.

Still, the relationships among Nickelsville and SHARE, LIHI, the city and county aren’t always smooth. Nickelsville hosted a tent city on church property south of downtown at South Dearborn Street from 2014 until this spring, when a collapse in leadership and a breakdown of the rules caused the camp to lose its church support and disband. A faction has been trying to establish a camp that allows drug use ever since. SHARE currently has over 150 people encamped on the plaza of the King County Administration Building — in an unpermitted, unsanctioned tent city — because of a funding dispute. The organization is routinely accused of not focusing enough on trying to help people out of homelessness. Dee Dixon, a case manager at Othello Village, says sometimes it seems like long-term campers coming from other SHARE or Nickelsville tent cities are wary of LIHI’s involvement. SHARE and Nickelsville staff say LIHI sometimes oversteps its bounds, particularly at Othello Village, circumventing the self-governance model.

Internecine conflicts aside, there’s no question that people are moving more quickly from the three city-funded encampments into housing than from SHARE’s other tent cities or the former Nickelsville Dearborn site. Between October 1 and June 3 (Nickelsville Ballard and Tent City 5 opened in November; Othello Village in March) 44 people have moved from a camp into permanent or transitional housing, the majority in buildings operated by LIHI. Families in particular tend to move through quickly because they get priority housing in many programs. Lee cites the example of a family who showed up at Othello Village with a 6-day-old newborn, and was moved into housing two days later.

But there are also plenty of residents who aren’t ready for housing, at least not right now. Some say they would genuinely rather live outside. Some are transient, having been homeless elsewhere — in Phoenix, in Houston — and come to Seattle because they heard it was a better place than others to be unhoused. One Othello Village resident who works full-time tells me he did his research before he came to this city. “Seattle takes care of its homeless. I thought, if I get in an encampment, get a job, boom, I’m good,” he says. He’s content to stay in camp for the time being, maybe until November. “I could get out of here quicker, you know, but you get comfortable.”

Others, like Johnson at Tent City 5 and J.R. at Othello Village, characterize the camps as essential stepping-stones. Critics, including Sacramento’s homeless services coordinator, who visited this spring, have said that even the city-funded camps focus too much on internal community building and not enough on moving people into more traditional housing. Johnson and other residents say community building isn’t incidental: It’s the point. SHARE prides itself on its “peer-to-peer resource sharing,” the understanding that residents will educate each other about programs like free clinics and food banks, even absent a formal outreach worker. By their reasoning, just being expected to participate in a microcosm of civil society is part of the camps’ benefit. Johnson suggests other ways of measuring improvements to campers’ lives, besides housing placement. “Is it period of time off of drugs? Is it complying with your correction officer? Is it, obviously, work? Volunteering, school?”

“I’m not saying housing is bad, just saying as a single indicator of success, it’s a far cry [from capturing the whole picture],” he continues. “For a lot of people, putting them into an apartment by themselves right away doesn’t help them.”

J.R. checks me in for a night at Othello Village. As bookkeeper, he oversees the camp’s paperwork.

It’s a sentiment I heard from multiple residents, but which is seemingly at odds with current HUD policy. Since 2009, HUD has been de-emphasizing transitional housing because of its high costs and uneven track record. Despite its hefty price tag, studies have shown that participants are typically only moderately better off afterward. HUD has been pivoting toward the Housing First model instead.

Seattle has long been a pioneer in Housing First. The 1811 Eastlake project, for example, a building where chronic alcoholics exiting homelessness are permitted to drink, is recognized nationally as a success. But Johnson and others are saying there’s still value in these “transitional zones,” so long as they’re flexible to residents’ needs. Ready to go back into market-rate housing in two weeks? That’s possible from a tent city. Need a job first, behavioral therapy, a few years? That’s possible too.

“In the absence of a systemic solution that realistically addresses homelessness and the massive wealth inequality in our society, we need safe spaces to transition from public space into private housing,” says Graham Pruss, a former homelessness outreach worker who researches vehicular residency and sits on the board of All Home, King County’s Continuum of Care. He’s spent the past six years advocating for the creation of safe parking spaces for people living in their cars and RVs. An estimated thousand people live in their vehicles in Seattle; Pruss thinks they should be recognized and mobilized as the provisional emergency shelters they are. Earlier this year, the city followed his advice, creating two safe “zones” with minimal services and one safe “lot” with cooking facilities, paid on-site staff and case management.

Pruss thinks the fact that all three parking lots filled to capacity immediately demonstrates how necessary they are, and feels the city’s support of them has been too haphazard. This spring, the owners of 25 RVs in the safe zone in Interbay got a rude awakening when they were informed they’d need to move to a new site by the end of the week. The new site is on the other side of the city and can accommodate only 15 RVs. The encampments and RV areas occupy an uncertain space in the homeless services continuum, particularly when it comes to providing services beyond case management.

“At this point I still think that the authorized tent cities are a bit of a missed opportunity,” says Harris, of Real Change. “While Seattle is experimenting with them and allowing them, they’re a long ways from going all in and really offering them the resources that they need.”

The camps don’t serve people with mental illness or serious addictions very well, for example. In a few situations, camps have had to bar residents with schizophrenia, or even, in one case, autism, when their challenges got in the way of enforcing the rules. When that happened, residents didn’t know where to send people.

James Jones, an Othello Village camper everyone calls J.J., wishes the encampment could offer more formal employment support, like classes in resume writing and interviewing. On a late-night security shift, he picks up an empty frosting container another camper lent me to use as a cup. He says he’s been homeless four times, and while Washington State has given him the most support of anywhere he’s been, he stills feels he never gets the help he needs to avoid becoming homeless again. “They just run you in circles,” he says, and spins the frosting container. “I’ll be 40 in a few months.” Spin. “Soon I’ll be 50,” he says. Spin. He doesn’t still want to be in a homeless encampment then.

J.J. sits on a late-night security shift. “Some shelters, you have to take your stuff with you, how can you get your life together like that?” he asks.

When officials from Sacramento visited Seattle’s camps earlier this year, the lack of connectivity was a takeaway for them too. Emily Halcon, Sacramento’s homeless services coordinator, joined city council members, the city manager and chief of police on the tour, arranged by a Sacramento lawyer who wants to test a similar model in the California capital. She was impressed by the camp’s cleanliness and management, but determined that the model, as it works in Seattle, wouldn’t solve Sacramento’s homelessness woes. “And I’m not sure they solve the biggest problem in Seattle,” she says. “It’s not the tent itself, it’s the operations and being a part of the continuum of care as opposed to something that just stands on its own.”

Barbara Poppe, of course, is one of the encampment model’s highest-profile detractors. Supporters of the camps say the Murray administration’s choice to hire her as a consultant so soon after sanctioning the creation of three camps sent a clear signal of the administration’s ambivalence. At a press conference in June, Poppe repeated her stance that camps do not meet basic requirements of housing. While she acknowledged that the tents may be better than sleeping on the streets, the fact that people have no choice but to sleep outside was very sad, she said.

Jason Johnson of Seattle’s Department of Human Services says Poppe’s stance is “nothing controversial” to the city. “I think the mayor has been very clear that sanctioned encampments are not the solution. We made land available and a little bit of operating dollars available to make what’s a really hard existence, living outside on the streets, a little bit better” he says, “but by no means has this mayor or department ever said that encampments and having people sleep in tents is the solution.”

Poppe has also made clear that the encampments are far from the only distraction standing in the way of long-term solutions. Seattle has developed an array of successful programs, she recognizes. Yet in conducting her analysis of how peer cities are addressing homelessness and how Seattle might develop the most effective framework for investing in services, Poppe saw a system that is needlessly complicated. At least 350 programs to address homelessness exist in Seattle, operating across 135 different providers. “That’s a lot of complexity, and a lot of small programs, and that makes everything so much more challenging,” she said.

At the June 9 press conference, Poppe didn’t elaborate on which programs might need to be reconsidered. She did emphasize that she has two major priorities for Seattle: reducing unsheltered homelessness and ensuring more people are moving more quickly from emergency services to permanent housing. To do so, she announced her support for 24/7, low-barrier shelters with a focus on housing placement. Not encampments, but indoor shelters, modeled after the Navigation Center in San Francisco.

That facility practices what Executive Director Julie Leadbetter calls “radical accommodation, radical hospitality.” The shelter serves about 75 people in a dorm-style setting. Men and women aren’t segregated and have some flexibility around their living space (couples can push their beds together, for example). Much like Seattle’s encampments, pets are welcome and there’s no limit on how many belongings residents can bring.

Leadbetter says the real innovation at Navigation Center is coordinating services. The center has an intensive commitment to housing placement, and the full backing of city resources to make that a reality. Units across the city’s supportive housing portfolio are prioritized for Navigation Center residents. All the other resources they’ll need to get and stay housed are brought onsite: connections to jobs programs, sign-ups for benefits, intensive behavioral care.

So far it’s working, very well. Just as Leadbetter is explaining all this to me, she gets interrupted. “There’s some keys to an apartment being dangled in front of me, hold on a second, I have to give a hug,” she says. When she comes back to the phone, she laughs, “It happens here all the time, which is such a nice feeling.”

In June, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed legislation mandating the creation of six new Navigation Centers over the next two years. The same day Poppe made her recommendation in Seattle, Murray announced a plan to launch a Navigation Center-style facility in Seattle too. It was a marked departure from what Poppe told the media she’s observed while consulting since September. “I love all of you in Seattle,” she said, but the city is not, on the whole, action-oriented, she continued. “It is a community that is much more inclined to discussion and planning and process that goes on and on and on.”

For now, the long-term plan for the city-sanctioned RV sites and encampments seems far from certain. The Ballard RV lot will close in August. Another in SoDo closed on July 1. TC5 and Nickelsville Ballard have a one-year lease with an optional one-year renewal. Othello Village can stay until LIHI is ready to develop an affordable apartment complex on the site. After that, who knows. “My expectation is that we will have established tent cities in our city for a number of years,” says Council Member Mike O’Brien, who has been a strong supporter of the encampments. “I think that eventually they will go away, and I don’t know how far out eventually is.”

A man named Robz was living at the RV safe parking zone in Interbay a week before the site closed and campers were expected to move.

Pruss has presented to All Home a tiered model of sanctioned car camping: from streets where people can park without fear of being towed and see a case manager once a week, to more consolidated lots with sanitation, social services and more active case management, up to small, quiet church parking lots where families who are ready to immediately move into housing can stay temporarily.

Andrew Heben, author of Tent City Urbanism and co-founder of the Village Collaborative, envisions a tiered model of sanctioned encampments too. At the simplest is the “sanctuary camp,” a traditional tent city that serves as an outdoor, low-barrier emergency shelter. Then there’s the “transitional village,” a set-up more like Othello Village, with its tiny houses and focus on housing placement. In Heben’s schema it’s seen as an intermediate stage to the “affordable village,” essentially a tiny house community, a neighborhood — permanent housing.

“We’re not willing to accept that [tent cities] are going to be around for a while so we define them as temporary,” he says. “It’s sort of like this cruel optimism” — not changing the policies that might lessen homelessness but not allowing successful provisional models to proliferate either. “These tent cities are going to stick around, so we might as well, instead of evicting them from place to place, we might as well work with them and develop the physical infrastructure of these places so that they can be places of some quality.”

In his book, Heben identifies at least 10 existing villages, including Opportunity Village, which Heben helped establish in Eugene. That transitional village has housed about 90 people in 30 tiny houses since opening in August 2013. Now the same nonprofit is working on a new site, Emerald Village, which will provide permanent affordable housing to residents who can’t afford market-rate housing or find affordable housing through more traditional channels, but who can pay a small amount of rent with a fixed income or part-time work. Emerald Village’s rents will be around $250 to $350 per month.

In Austin, Community First! Village has already established such an affordable village. Just outside the city, literally abutting a fence that marks Austin’s edge, Community First is a master-planned, 27-acre community of 120 tiny houses, 100 RVs, and 20 canvas-sided tents. An on-site organic farm supplies free fresh vegetables and work opportunities for residents. There are honey bees, goats, chickens, a tilapia farm, and a soon-to-be-built commercial kitchen where residents will be able to learn to make and sell value-added products. At a blacksmithing shop, residents can learn the trade, profit from their creations and teach visitors how to blacksmith themselves. There’s a city bus stop there. A clinic is moving in too, and there’s already both a hospice center and a columbarium for interring cremated remains.

It’s essentially a neighborhood for the chronically homeless. People must have been unsheltered at least one year and have a disability to qualify. And they have to pay rent, between $220 and $380 a month, depending on their housing type. (The RVs have full hook-ups, whereas the tiny houses have shared kitchens and bathrooms.)

“We call this a 250-bedroom, $14 million and a half mansion,” says founder Alan Graham, referring to the price tag for the project, nearly all of which was raised through private donations. “We’re trying to expand what home really means.”

A local movie theater has constructed an outdoor movie screen where the public is welcome for free movies on Friday nights. It’s ringed by trailers, tiny houses and even enormous teepees that will serve as a bed-and-breakfast for church groups and other volunteers to stay on site. (Community First! Village is a project of Mobile Loaves and Fishes, a Christian organization that grew out of a food truck ministry.)

The night I visited was a movie night. Bonnie Durkee, a veteran amputee who had been living in a tent for years before moving into her RV, was doing laps around the village. “Shorty” was working concessions, as he always does, even though he still sleeps in the doorway of a law office downtown while he waits to move into his tiny house. When he does, he will be ending a stretch of homelessness that’s lasted 31 years. In all that time, Shorty’s been offered plenty of case managers and services; recently, after scoring high on Austin’s coordinated entry assessment, he was put on a housing waitlist. “But when I heard about this place,” he says, looking out at Community First, “that changed my perspective on trying to get an apartment. This right here, this is all I want.”

HUD’s Portland Field Office is on board with the model too. A May 2016 report on the feasibility of tiny house villages in one Oregon county determined that they’re “a good solution to increase affordable housing stock in Lane County, Oregon. It is also projected that tiny home villages will create communal support, benefiting residents’ likelihood of long-term housing, employment, and contentment.”

This year, one such village opened in Seattle: Nickelsville at 22nd and Union, a cluster of tiny houses on church property in the Central District where residents pay $90 a month, again in partnership with LIHI. While no bigger than most of the Othello Village sheds, the units have electricity and heating, and the site has a real bathroom and shower. According to the city, it’s still not housing. “We still consider those individuals that lived in those built structures living unsheltered, still remaining homeless,” says Johnson of Seattle Human Services. When the one night count is taken next January, that is, they’ll be counted as living outside, not even among those in emergency shelter. Another nonprofit housing provider announced in late June that they’re creating a temporary “community for people transitioning out of homelessness” using modular steel structures. A spokesperson says the model aims to provide housing for whatever stage people are in, to “meet people where they’re at.”

Across the city, from Tent City 5, to Othello Village, to 22nd and Union, residents told me they were done with camp living — done with the interpersonal drama, done with the stigma. “It’s degrading,” one TC5 camper says. But others, far more, told me they were grateful, that this was world’s better than where they were before, that they’re content for now, whether or not they’re working to move into housing later. After living outside, an apartment “feels stuffy,” says a woman at Othello Village.

“You need a whole range of options,” says Harris. “A lot of people are perfectly happy living in an RV. I think one of the things we’re in denial about, is how deep the structural housing crisis is in this country. And there are a lot of people who are just not in the system and have been failed by the system. There is a huge, huge need out there.”

As Heben sees it, tiny house villages present a viable option not just for housing the unhoused, but for living more sustainably at a time when there is growing recognition that our cities can’t keep expanding and we can’t keep consuming resources at the rate we’re accustomed to. As Pruss sees it, vehicles are already being used for emergency shelter. If they’re brought to a central location and their owners are given support, they can begin to consider other housing options, without worrying about being chased around, ticketed or towed. To Harris and others, it comes down to a question of intentionality: Why can’t existing emergency shelters be transformed to operate more like the Navigation Centers, with fewer barriers and a greater focus on housing connections?

For Charlie Johnson, two months after we first spoke, Tent City 5 is still his first choice. “Even though quality of life isn’t great, and I’m still not in good shape, at the very least, when I’m able to block out some of the bigger stuff, I’m able to do what I’ve got to do there. So it’s helping a lot,” he says, “Being forced to be around people and having people turn to you all the time, it helped pull me out of myself.”

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Jen Kinney is a freelance writer and documentary photographer. Her work has also appeared in Philadelphia Magazine, High Country News online, and the Anchorage Press. She is currently a student of radio production at the Salt Institute of Documentary Studies. See her work at jakinney.com.

Follow Jen .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine