Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberOn a late December night in the Anacostia section of Washington, D.C., more than 100 residents, from infants to octogenarians and everything in between, gathered in the basement of Union Temple Baptist Church. They were there to observe the second day of Kwanzaa, the now 4.5-decade-old African-American holiday tradition. Each day of the seven-day festival is dedicated to one principle. Day two’s is Kujichagulia, the Swahili term for self-determination, and in a few moments the crowd would be watching Flag Wars, a 2003 documentary about a black community’s resistance to and reconciliation with gentrification in a Columbus, Ohio neighborhood. I had been sent to the gathering by a woman named Luci Murphy, whom I had only spoken to via e-mail about the story I was writing on the old and new D.C. Although Murphy couldn’t make it out herself, she thought it would be a good opportunity for me to hear how longtime residents were thinking and talking about the city’s makeover.

I had a look around the basement as I was waiting for the main event to begin. Most of the people had already taken their seats. A few were in line to buy dinner or a refreshment at the concessions window. Vendors dressed in African wraps and dashikis peddled tchotchke in the back of the room. A picture of President Obama, ornate African tapestries and several photo albums containing snapshots of the prominent African-American athletes, entertainers and ministers who’ve graced the church’s pulpit through the years adorned the walls. Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan, former D.C. mayor and current City Councilmember Marion Barry, singer Erykah Badu and former heavyweight boxing champion Riddick Bowe were among the faces I recognized. But judging by their weathered condition and the pre-millennium dates on the Washington Post stories featuring the church’s controversial pastor, Willie E. Wilson, Union’s heyday — like the District’s “Chocolate City” moniker — appeared to have come and gone.

Finally, after an inspired drum performance, the lights dimmed and for the next 90 minutes we watched uncomfortable dinner table talk about race, class and crime rub up against the classic NIMBY skirmishes. For many of the folks in the audience, Flag Wars was the story of their lives: The city they’d always known was becoming a foreign land before their eyes, and they were no longer sure if and where they fit in. Upscale markets, old neighborhoods with new names and amenitized buildings were commandeering the nation’s capital, and it didn’t appear that any of it was being made with their means or ways of life in mind.

Three panelists addressed the audience following the film. Dr. Frances Cress Welsing, a polarizing psychiatrist and author whose views have been called racist, told the audience that she was being pushed out of her home of 40 years on 16th Street in upper Northwest. (D.C. is divided into four quadrants, denoted by the ordinal directions.) The 77-year-old wasn’t being priced out, however. Welsing charged her neighbor, the Jewish Primary Day School, with flouting a written agreement to maintain a 15-foot noise buffer between her home and its new playground. It was her position that the school was intentionally creating an unlivable situation for her so that she would sell her property on the cheap. I found the notion that a school would use small children to make an elderly woman’s life a living hell repugnant, but I also registered the empathy on the faces in the crowd. For many, Welsing’s plight was yet another example of the coup d‘état taking place in the city.

The District now owns the highest fraction of households making over $200,000 a year and a greater income divide among the rich and poor than in any state in the country.

“This is aggressive gentrification,” the snowy-haired Welsing declared. “We have to stand together and speak out. The more you talk about it, the more you realize it’s happening to different groups of black people in different ways. It’s like the old saying where black people have no rights that white people are bound to respect.” Welsing paused briefly to receive the audience’s tart applause. Beside her, Reverend Wilson folded his arms over his stout stomach and offered a vague nod. She went on: “We have come too far in our struggle as black people to get pushed out of the city because some people want to come back and they don’t want us in the city with them.”

Sixteenth Street’s racial discord precedes Welsing’s conflict with the school by almost a century and a half. In the late 1880s, a U.S. Senator’s wife orchestrated the removal of a black community in what is now Meridian Hill in order to turn the street into the “Avenue of the Presidents.” African Americans were barred by custom and covenant from buying any of the street’s Victorian homes well into the 20th century. Once they gained the right to live on the street, white homeowners moved west of bucolic Rock Creek Park or out of the city entirely. To this day, 16th Street, which cuts a narrow swath through three wards from downtown D.C. to Silver Spring, Md., serves as a de facto dividing line between white and black Washington. Ward 3, the city’s westernmost section, is nearly 80 percent white and exclusively upper income, for all practical purposes. It contains swanky, secluded enclaves with names like Spring Valley, Foxhall, Friendship Heights and Chevy Chase, neighborhoods where the average family income is more than a quarter-million dollars and the median home is valued a shade below $900,000, where high-end shopping, green space, markets, eateries, elite schools, hospitals and parks are plentiful.

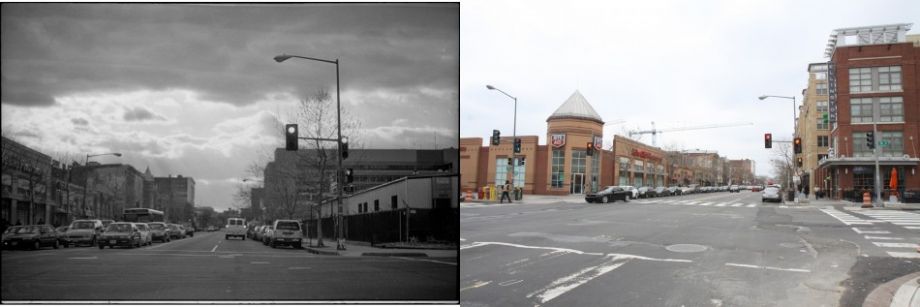

1250 U Street NW, 1999-2000 and present day

Meanwhile, Ward 8, the city’s southeastern-most section, feels something like a deep southern town from a bygone era. It is physically isolated from the city’s core by the Anacostia River and bereft of the upscale accoutrements that characterize the new D.C. The luxury condos that now crowd the city’s skyline haven’t arrived. Neither have top-end retailers, nor the bars, lounges and restaurants that people who’ve moved to the city in recent years rave about on food and culture blogs. With 94 percent of the population African American, it is rare to see anyone who isn’t black or brown. In Ward 8, the average family income is $44,000 and falling. The median home’s value — the ones in sellable condition — is $229,000, less than half the citywide average and on a steady decline as well. A quarter of the population is unemployed and the poverty rate stands at 34 percent. At night, the side streets are barren and dark. Cops dispersing groups of young black men or searching their cars is such a common sight that it barely registers a glance from passing drivers. Older men hover around the sidewalks in front of liquor stores. Church basements like Union’s notwithstanding, the dining options are fast food or faster food.

“This looks like 1960,” El Senzengakulu Zulu said after Welsing concluded her remarks. “I’m in Mississippi trying to help the brothers and sisters register to vote.” A former SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) member and a Freedom Rider, Zulu’s organizing history includes campaigns alongside likes of Martin Luther King, Medgar Evers and a young Marion Barry. Wearing an embroidered kufi and dashiki, the founder of one of the nation’s oldest independent black schools — Ujamaa — clutched the microphone and surveyed the room like a tired parent. “This meeting is exactly the same,” he said. “We are fighting the same old fight.”

Reverend Wilson closed out the night. Honey brown and bald with lamb chop sideburns that harken back to the days of Shaft and Superfly, the one-time mayoral aspirant decried the need for black people to be “proactive” and not “reactive” in the fight against gentrification. He urged the audience to support Welsing by demanding the city leadership do something for her and other black residents facing displacement. Then the reverend beckoned the audience to stand and hold hands. A prayer ensued. And on his command, the collection bowl made its rounds.

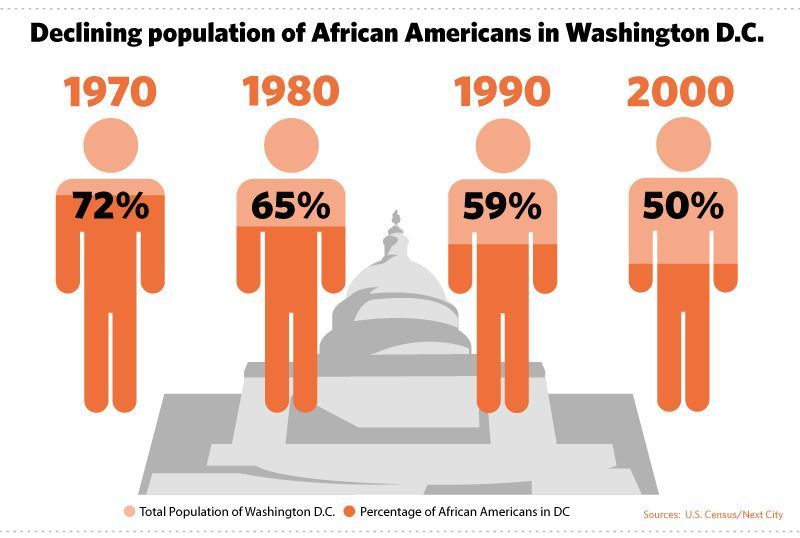

The assertion that black people are being “ethnically cleansed” from D.C. is not new. Residents have openly discussed a so-called “plan” to remove blacks from power in the District since the 1970s. Every local publication, the Washington Post included, has weighed in on its existence. The “plan” even has its own Wikipedia page. From a purely statistical perspective, the view, held by a surprising cross-section of residents, has currency. Four decades ago, blacks made up 72 percent of Washington, D.C.’s population. Three decades ago, 65 percent. By Census 2000, the percentage had fallen to 59. In Census 2010, a shade over 50 percent of D.C. residents checked the box marked black/African American. That African Americans no longer hold majority status in the city is practically a foregone conclusion.

Not only did the percentages of blacks decline, but between 1970 and 2000 the city’s overall population contracted from more than 760,000 to fewer than 570,000. In striking contrast, the District netted 30,000 residents in the first decade of the new millennium and was noted as the fastest-growing state or territory in the country between 2010 and 2011 by the Census Bureau. The lion’s share of this growth stemmed from white in-migrants. D.C. saw its white population swell by 32 percent (50,000) in the first decade of the millennium.

But saying that race alone sparked the Union Temple gathering would be inaccurate and ahistorical. D.C.’s white population has never dipped below 27 percent since the Census Bureau began keeping records on the city. And while race relations have been turbulent at times over the past 40 years, cross-cultural fellowship has been central to the city’s identity. What’s different, now, is the character of its growing divisions. The District now owns the highest fraction of households making more than $200,000 a year and a greater income divide among the rich and poor than in any state in the country. You may think that as disconcerting as this all may appear, unbalanced income distribution is not exactly new to D.C. or unique to the country. A revolving army of federal contractors, lobbyists, lawyers, policy wonks and media professionals has always earned princely wages in the nation’s capital. Likewise, the United States currently has the greatest wealth divide, highest poverty rate and lowest social mobility in the industrialized world. The growing concern with D.C.‘s widening divide — and the reason gatherings like the one at Union Temple even exist — is that its neat split along racial lines is engineering a new city for new residents based on an old caste system. While the median white household’s income in 2011 was $99,220 ($45,052 more than the national median for those households) median income stood at a modest $60,798 among Hispanic households and a paltry $37,430 among black households.

The data about growth and change in modern D.C. has been well documented, but the story behind how it happened, and what it’s meant, has been given scant attention. On January 2, 2003, then-mayor Anthony Williams stepped to the Warner Theatre podium to deliver his second inaugural address. Themed “One City, One Future,” the mayor touted his administration’s many successes over the previous four years and acknowledged the challenges that lay ahead. Nearing the end, he shared a vision for residential development that has since been cited as the first public declaration of the city’s makeover blueprint:

Through a range of homeownership efforts, including attracting market-rate housing, we can develop at least 15,000 new homes as part of our goal to bring 100,000 residents to the city within 10 years. We must lure back residents who fled the city in the past, but not at the expense of those who today call the District home. We can do this. We will do this.

Adding 100,00 residents in a decade sounded like one of those pie-in-the-sky ideas that leaders use inaugural addresses to dream publicly about. After all, the city’s population had been shrinking for five decades straight. But the number wasn’t just a dream. It had come straight out a 2001 research brief co-authored by Alice Rivlin, the economist who, two months after the brief’s publication, completed a three-year term as the head of the control board that had been managing D.C. at the federal government’s behest since the mid-1990s. Titled “Envisioning a Future Washington,” the report proposed an intrepid plan for securing the city’s economic future. “The overall racial and ethnic mix of the city’s population has not shifted radically,” the authors wrote of their invented D.C. of 2010. “African Americans retain a slight majority and immigrants from Central America, Asia, and Africa are a significant presence in the city as well as in the rest of the region.” Oddly, the authors failed to mention white people in this vision.

“The key seemed to be economic development in the city,” Rivlin told me when we spoke. “But of a kind that would grow the population because if you just create jobs, many of them are held by people who don’t live here and that doesn’t help the financial base, because we can’t tax the incomes of people who work in the city and who don’t live here.”

“It was an eye opener. People were looking at the zip code and not calling back for basic entry level positions based on the part of the city we lived in.”

In addition to prohibitions against non-resident taxation (60 percent of the workforce) and tax-exempt property (40 percent of all land in the city), the city’s unique arrangement with the federal government forbids it from building beyond strict height limits. A 2003 Government Accounting Office report estimated that the city lost $1.1 billion in revenue each year from these restrictions.

“Congress has decided that,” Rivlin said of the restrictions, which are embedded in the 1973 Home Rule Act granting the District limited governance over its affairs. “I think it’s the wrong decision but I don’t think it’s going to change. So the District has to cope with the fact that it has to grow not just jobs in the city, but jobs for D.C. residents. Good jobs for D.C. residents.”

Rivlin’s co-author, economist Carol O’Cleireacain, offered two pathways to stabilize the city and prevent another crisis. One option was to attract middle-income families with children. “They might be teachers, law-enforcement officers, nurses and other medical service providers, university faculty and staff, and professional, technical, and clerical workers in both government and the private sector,” the authors wrote. But the authors cautioned that this strategy would result in budgetary losses, higher taxes on households without children and would require a massive restructuring of the school system.

The other option was to attract and retain middle- and upper-income singles and couples in their 20s and 30s without children. “This strategy,” Rivlin and O’Cleireacain wrote, “would further increase the ratio of adults to children in Washington’s population, raise the proportion of people in upper-middle income brackets, and probably increase the ratio of whites to African-Americans in the population. This strategy could make the city more livable and attractive for both current and new residents by increasing the potential clientele for restaurants, shops, and entertainment venues.” The authors estimated this route would yield $300 million in revenue over expenses annually, but acknowledged that it posed a “serious risk of exacerbating racial and class tensions and widening the gulf between rich and poor in the city.”

The report did not advocate for one alternative over the other, but the city’s new character speaks for itself.

Corner of 13th and U Streets, 1999-2000 and present day

“The decade wasn’t the same,” George Mason University demographer Lisa Sturtevant cautioned me when I asked her about the boom. She has spent more time analyzing the District’s demographic trends since 2000 than anyone in her field. Sturtevant contends that it was the recession in the latter half of the last decade that made all the difference for D.C. During the early part of the recovery, she said, the only place that was adding jobs was the Washington, D.C. metro area. “So if you graduated in ’07, ’08 or ’09 and you wanted a job, you came to Washington. You look at the 15 largest metropolitan areas as they were recovering and we were the only one. We have the federal government here and it gets ramped up during recessions.” Indeed, between 2008 and 2010 alone, one-quarter of the people who moved to D.C. came to work for the federal government, nearly 2.5 times the normal rate for the same period, IRS data shows. More than 72 percent of the new residents hailed from outside of the Washington area — 80 percent for whites. Seventy-five percent had never been married and only 9 percent had children under 18. More than 67 percent had at least a bachelor’s degree. Nearly 54 percent of the newcomers were white. Meanwhile, African Americans made up 40 percent of those who disappeared from the city, nearly half landing close by in the first-ring suburbs of Prince George’s County.

Part of the explanation for the disparity and resultant exodus is poverty. Fully one-quarter of the District’s black residents and half of its black children live in poverty. The criminal justice system serves as an interrelated barrier. The link between poverty, race and incarceration in D.C. is beyond dispute. Nearly 90 percent of D.C.’s incarcerated population is black and in 2011, blacks made up more than 94 percent of the youth arrested. At least 90 percent of the estimated 60,000 residents with criminal records are black. Put differently, one in five black people in the city has a record, and since the vast majority of those arrested and sentenced are males, a more accurate figure is closer to one in three. It’s no real surprise to anyone that nearly half of those residents with records, about 28,000 people, are among the ranks of the unemployed.

Another factor going against D.C. residents may actually be the simple fact of their D.C. residency. For more than a year, Dawn Matthews was the resume specialist at a Ward 8 job readiness center called Training Grounds. The program offered an intensive unpaid six-week course to unemployed residents of the Southeast D.C. neighborhood of Parkside. Participants were required to show up every morning at seven dressed in proper work attire — no exceptions, no excuses. They went through soft skill training, conflict resolution training, computer training and mock interviews. At the end, Matthews polished their resumes to a spit shine and made sure they got out the door. But even her most promising clients didn’t hear back for entry-level positions at Giant and Target.

“It was discouraging,” said Matthews, a District native. She had faced her own prolonged bouts of unemployment and could identify with her clients’ struggle. “You’re trying to keep them from going back to the streets, but when you cannot get a job and you have children to take care of, family, what do you do? When the door doesn’t open, you’re going to go back to what you know.”

Nearing her wits’ end, Matthews talked her boss into letting her run a resume experiment. First, she sent out her resume for the same jobs her clients had applied for just to see if she heard anything back. Again, crickets. Next, she replaced her Southeast D.C. address with that of her father in Fort Washington, Md., and sent the exact same resume back to the same employers.

“Within a week I was getting callbacks,” said Matthews, who later left Training Grounds in part due to her frustrations. “It was an eye opener. People were looking at the zip code and not calling back for basic entry-level positions based on the part of the city we lived in.”

Kadidia Thiero, a Georgetown-educated D.C. native, has received notice that her rent will be double what she paid in 2000. She says she doesn’t make enough to move.

Whether you subscribe to the idea that discrimination is at play, the city’s growing socioeconomic divide has had an unquestionable impact on the housing market. Throughout the city, home prices doubled and in some cases tripled from 2000 to 2010. Over the same period, D.C.’s median rent for a one-bedroom apartment rose from $735 to $1,100. A 2012 National Low Income Housing Commission report found that only Hawaii had higher rental costs for two-bedroom apartments. Even as the recession has cooled housing markets in the rest of the country, rents in D.C. have continued to rise at a faster rate than they had in the seven years before the meltdown. Meanwhile, during the same span, D.C.’s stock of affordable housing has been cut in half and its percentage of low-value homes has depleted by nearly 75 percent.

The situation has left middle-income renters like Kadidia Thiero scratching their heads and wondering how they’re supposed to survive.

“I can’t put together two pennies and people are willing to pay $700,000 for $300,000 homes?” the 43-year-old asked incredulously.

Thiero is among the 60 percent of childless D.C. singles paying at least half their income in rent, a figure the Department of Housing and Urban Development considers a severe housing burden. An educator who holds degrees from Howard University and Georgetown, Thiero has lived in D.C. all her life. She grew up along 16th Street, works in LeDroit Park and sits on the board of a non-profit in Mt. Pleasant. She knows all of her local shopkeepers by name and is an active member of the local arts and culture scene. Yet none of her sweat equity in the community has mattered to the company managing her building. It has raised the rent on her studio every year since she moved in, even when she lost her job during the recession. She finally asked for an explanation when she received a notice that her rent would be double what she paid in 2000. “I was told that similar apartments in the neighborhood were renting for an additional $300.”

I asked Thiero why she just didn’t look for a new place to live. She told me it had taken her two years to find her new job and it paid $20,000 less. “Honestly, I don’t make enough to move,” she said.

Believe it or not, Thiero is one of the fortunate ones, as she’s been able to figure out a way to stay in her hometown. I witnessed a byproduct of local dislocation one night while sitting with a young attorney from the Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless. Will Merrifield was on the phone scrambling to find a shelter to take his client, a 20-year-old who was nine months pregnant. It was one of the coldest nights of the year, and she and her two small children were somewhere in D.C. standing on a corner with no place to go. The county’s shelters wouldn’t take them because she didn’t have Maryland ID. The ones in D.C. were refusing her because she was receiving Maryland benefits. Both claims were true: She’d been living between two of her husband’s relatives for the past year. One lived in D.C. and the other in Prince George’s. Given their proximity to one another, it’s not uncommon for people, especially blacks, to have ties in both locations. For more than an hour, Merrifield pleaded with area shelters to take his client. Finally, he called her with news.

“You should try a hospital emergency room,” he told her. He promised to call first thing in the morning and to do whatever he could, which, these days, often feels like very little. The affordable housing waitlist is 15 years long. The Section 8 waitlist is 25 years long. He fields calls every day from residents working minimum-wage jobs and living in their cars. Merrifield sighed and told me that this — the widening services gap and the people caught in it — is also the face of gentrification.

“My day-to-day is in a really depressed state,” Merrifield told me. “A lot of advocates find a way to turn it off. But a lot of us don’t and it’s tough to go to work every day. It’s tough when you think the game is rigged. And it does seem rigged. I think there’s an absolute racial component. It’s just easier to marginalize poor black folks than it is to marginalize poor white folks.”

A native of Youngstown, Ohio, Merrifield has been living in the District for all of 18 months. He’d never been to D.C. before he moved and knew nothing about the city’s history and politics until he started spending time with his clients and showing up to community meetings, where he got to see firsthand the breadth and scope of the housing problem.

Will Merrifield is an attorney from Ohio who recently moved to D.C. for a job providing legal aid to the city’s most vulnerable populations. He worries about the impact of transplants like him on the housing market.

“How do you get yourself out of poverty if you don’t have stability in your housing?” the raspy-voiced attorney asked me. “I grew up with every single advantage. My dad had his own business. He put me through college and law school. And it was still hard for me to go out and get a job because I wasn’t confident enough. Me! I could’ve never done what I do now without that support, so to expect people without even housing to do so is morally bankrupt. It’s indefensible.”

True to his word, Merrifield didn’t give up. He kept badgering the shelters with his client’s plight. Two days after we spoke, an emergency shelter on the old D.C. General Hospital campus accepted her and her children. She’s been there since.

Merrifield is a young, brash, single, childless, professional, privileged white guy who lives in ritzy Cleveland Park. If you go strictly by the prevailing gentrifier stereotypes drifting through old D.C. like noxious gas, he is not supposed to be aware or concerned about how the other half is getting along. Yet he is — so much, in fact, that I wondered how long he could last.

Gentrification, historically, began with a block. A few intrepid outsiders moved into a shady neighborhood. They were the risk takers. They invested sweat equity and financial capital into the community. Built up the block, and then the community, with their labor. Another wave of gentrifriers followed. Recently, demographers and sociologists have identified a trend they’ve coined “new build” or “super-gentrification.” In this scenario, tax breaks and other government incentives encourage commercial investors to stimulate the local economy. They build brand-new upscale retail and residential development — condominiums for the most part — in a previously depressed but centrally located community. The city starts calling the area “revitalized” and real estate agents market it as “up and coming.” Young professionals buy in with the expectation that their property’s value will skyrocket once a few more changes occur and, for the most part, they’re right. By and large, this is what has happened in D.C.

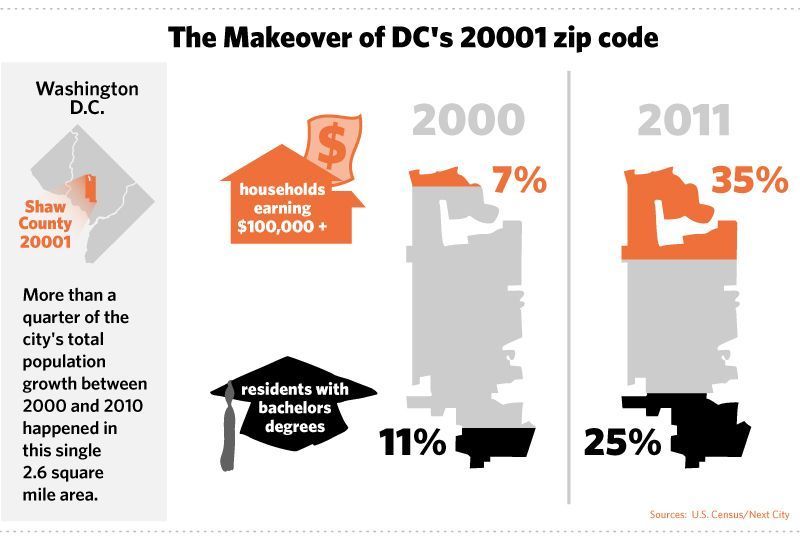

Seventy years ago, Northwest D.C.‘s 20001 zip code was the center of the city’s black intellectual and cultural life. Large tracts of the area, which includes the neighborhoods of Columbia Heights and the now-trendy U Street corridor, were destroyed in the uprisings of the 1960s and further depressed by neglect in the 1970s. Property values bottomed out in the 1980s as crime and drug use put the zip code into a sleeper hold. In the 1990s it became the site of a nightlife renaissance, but remained largely underdeveloped otherwise. By 2012, a Fordham University study had ranked the zip code as the sixth-fastest gentrifying area in the United States. New condos and retail have spurred much of that growth. In 2000, condos only accounted for 2 percent of the zip code’s home sales — six were sold in total. In 2011 alone, condos accounted for 57 percent of total home sales (276), most at triple the 2000 median price. The zip code now boasts an Ann Taylor, a Brooks Brothers, an Urban Outfitters, enough bars to serve several university populations at once and a mind-boggling 10 Starbucks.

Likewise, in the past decade the zip code’s demographic character has been inverted. We can start with education. In 2000, 11 percent of 20001 residents had a bachelor’s degree. By 2011, 25 percent held graduate degrees. The spike in education levels in turn triggered a wholesale switch in the zip code’s income levels. In the years between 2000 and 2011, the number and percentage of households earning $100,000 or more rose from 787 (6.6 percent) to 5,548 (35 percent) and median household incomes jumped nearly $50,000. Consistent with the average American’s perception and experience of gentrification, the zip code’s growth and change coincided with the departure of blacks and the arrival of whites. According to the most recent ACS data, some 7,500 blacks have disappeared from the 20001 zip code in the past decade, while some 9,000 whites have moved in. Whites now make up 33 percent of the population, which is 28 percent more than a decade ago. More than a quarter of the city’s total population growth between 2000 and 2010 happened in this single 2.6-square-mile area.

What’s telling about the zip code’s “new build” makeover is that it did not move the poverty needle. The zip code’s poverty rate is exactly what it was in 1980, 1990 and 2000 — 28 percent — and the child poverty rate is nearly twice what it was in 1990 (45 percent). This, I would contend, is the overlooked consequence of super-gentrification. Two different groups with two very different experiences of America are thrown together. Even though neither group’s members identify themselves as being wealthy, one at least has the education and social and cultural capital that allows it to access resources that can, in turn, make the neighborhood more desirable and expensive. Meanwhile, the other group has a sense of ownership over blocks and rowhomes kept intact despite deep challenges and very little support. No one was painting bike lanes or donating sidewalk garbage receptacles in 1980.

Both groups feel entitled and resent the other’s sense of entitlement. Over time the neighborhood’s revitalization engineers a rigid caste system eerily reminiscent of pre-1965 America. You see it in bars, churches, restaurants and bookstores. You see it in the buildings people live in and where people do their shopping. In fact, other than public space, little is shared in the neighborhood. Not resources. Not opportunities. Not the kind of social capital that is vital for social mobility. Not even words. Hence, stagnant poverty figures.

The “Parcel 42” affair is a prime example of what happens when these disconnected and unevenly resourced realities bump against each other. In 2007, the District selected a patch of city-owned land on 7th and R streets to build a $28 million mixed-use affordable housing project. The building was supposed consist of 112 apartments priced for renters earning up to 60 percent of the $107,500 area median income (AMI), or $64,500. The building would offer four rent tiers and reserve 16 units for tenants making 30 percent or less than the area median income. The plan sparked a contentious debate. The chair of the local Advisory Neighborhood Committee (ANC) — major players in each neighborhood’s development planning, though they wield no direct ability to enact policy — called the building a repeat of “the affordable housing built in the 1970s and 1980s that was so terribly unattractive.” Others flooded the blogosphere with their displeasure. Nearly all of their doom-and-gloom forecasts concerned design aesthetics, building amenities and the threat that a 100 percent affordable housing unit posed to the community. Meanwhile, One DC, a Shaw-based community group, staged protests and advocacy campaigns to keep the proposed project in place. The group saw the building as both a way for residents to get a foothold in the middle class and to ensure racial and social equity as the city prospers.

“There is a huge divide in D.C. between what is deemed ‘white liberalism’ and ‘black liberalism,’” said a city official who has worked intimately on D.C.‘s economic development policy and strategy over the past decade. Agreeing to an interview only on the condition of anonymity, he epitomized the conflicted space many lifelong residents I spoke to hold but are reluctant to articulate on the record. Like many 30- and 40-something African Americans who grew up in the District and went off to college in the 1980s and 1990s (like me, in other words), he has fond memories of a city most Americans jeered and avoided. He loved go-go music as a teenager and is proud he was raised in a majority black town. As an adult, he’s embraced the new D.C. — the one with rooftop lounges, cafés and chain sports bars — but is frustrated that the forces that have shaped city policy have stripped away so much of the African-American history and culture.

“On a national political level, we’ve always been and always will be Democratic,” he told me. “But when you go down into the local landscape or subscribe to the policy of all politics are local, that liberalism has a divide. White liberals in D.C. don’t give a shit about social services because they’re not of that element. White liberals in D.C. are more about quality-of-life issues as it relates to the lifestyle they want to have. It is bike lanes. It is dog parks. It is about state-of-the-art swimming facilities. It is about recreation centers. Capital Bikeshare. Car2Go. Streetcars. It’s about a way of life. Black folks want this stuff, they’re just not as passionate about it.”

Instead, many black residents want to know why the city seems to be bending over backwards to accommodate newcomers when they and their neighbors are struggling to simply survive.

“The problem is that the game has changed and we have a whole side of town, philosophically, that is still calling 1968 play calls,” the city official said. “One of my biggest frustrations has been that community leaders, pastors and non-profit leaders all come from this place of fear.”

The evolution of Parcel 42 illustrates the disconnect between competing definitions of liberalism in the new D.C. The original developer waffled on its promise for affordable housing once the complaints started rolling in. Negotiations broke down. The city blamed the developer and the developer blamed the city. Five years went by and the lot remained undeveloped. Then, last spring, the city solicited new development plans that only asked candidates to “maximize” the number of affordable housing units at or below 80 percent of the AMI ($86,000), but requiring no specific number or percentage of such units. In December, the ANC threw its weight behind a plan to build a 102-room hotel, a modest 22 units of affordable housing and ground floor retail that includes a trendy Milk & Honey Market. After its decision, the ANC expressed that one of the plan’s selling points was that the 24-hour hotel operation would increase security at the corner. The D.C. City Council is expected to affirm the ANC vote this spring.

The way the Parcel 42 deal has ultimately shaken out is a telltale sign of who does and does not have a power in the new D.C. Last year, two black city council members, both seen as strong advocates for affordable housing and equity in education and employment, copped to fraud and embezzlement charges. Both gave up their seat. Adding insult to injury, Mayor Vincent Gray — an African American who ran on a neo-civil rights platform — has been embroiled in an ongoing federal investigation into his connection to a shadow campaign that smeared his predecessor, Adrian Fenty, and led to questionable hires in his administration. Around these parts, even the whiff of corruption can unsettle city leaders. It has the potential to resuscitate the haze of impropriety that reduced the city’s credit rating to junk status during Marion Barry’s reign and automatically renews fears of another federal takeover. Any hope Gray has of losing the shady-dealings stigma and avoiding a one-term mayoralty now rests in his ability to keep the investment community happy, a fact made abundantly clear in his new 116-page, full-color, infographic-laden five-year economic development strategy. The document’s audacious “100,000 new jobs/$1 billion in tax revenue” slogan appears to advance the same vision Williams put forth a decade ago, just with less divisive language, “new jobs” having replaced “new residents.”

In his role, my source has seen firsthand the toll these scandals have taken on issues like affordable housing. “Leadership has been weakened,” he acknowledged. “When you’re sitting across from a developer trying to hold firm to something that you know is right, you can’t. The authority is not there.”

You can certainly make the argument that African Americans are just paranoid, that demographic shift is a matter of market economics. The haves are simply reaping the rewards of hard work and discipline, good choices, good education, good timing, etc. It’s no one’s fault that a much greater share of D.C.’s white residents happen to be haves. The trouble with this line of reasoning is that while the District’s new socioeconomic order isn’t the result of a secret anti-black plan, it is the consequence of more than a half-century of social and economic policy decisions in which race was often a key feature.

In 1957 the Census Bureau officially declared the District a majority African-American city. Overnight, the Fed-D.C. arrangement that denied residents the right to elect its own local leaders or vote for president became a symbol of the broader civil rights struggle for enfranchisement. Congress had to act, and in 1961 it passed the 23rd Amendment granting D.C. residents the right to vote in national elections for the first time in nearly a century. Three years later, Lyndon Johnson wrangled 85 percent of the District’s vote and tried but failed to pass a law granting D.C. residents the right to vote for their own officials — something they hadn’t done since Congress abolished the city’s Territorial Government in 1874 and President Grant appointed three commissioners to run the city. As a consolation, LBJ abolished the commissioner system and appointed a black mayor and mostly black city council. A year later, the city burned following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.

The District of Columbia Home Rule Act of 1973 was the compromise that came out of the unrest. The House Committee on D.C. retained final say over the city’s budget, unrestricted power to legislate on all city matters and an unqualified veto right on any permanent city legislation. In exchange, the city was allowed to elect its own leaders and awarded an annual payment.

“The degree of control Congress had over Washington essentially affected the federal payment,” Rutgers University history professor and ex-chancellor Stephen Diner told me when we spoke by phone. “When they controlled everything they gave more money. When they didn’t control it they give less money.”

“We didn’t get educated. And the so-called leadership was comfortable with people being ignorant because they don’t challenge you the way educated people do. Our leadership was not self-assured enough to take the challenge.”

Back in 1972, Diner, who is white, began teaching in the urban studies department at the University of the District of Columbia (then Federal City College) and became interested in the history of the city and its federal landlords. He noticed that Southern politicians were the ones who routinely sat on the District subcommittee. As the Republican Party moved further to the right, the appropriations process became a hotbed for social conservative issues. The committee used its control to ban the use of taxes for abortion services, block gay rights legislation, deny benefits for non-marital partners of city workers and very nearly impose capital punishment. Meanwhile, the District’s crumbling image was simultaneously fueling the right’s assault on Johnson’s “Great Society.” By the 1980s, the nation’s capital had devolved into its murder capital. Drugs and guns seemed to appear in every corner of the city. The city’s school system languished at the bottom of the country in graduation rates and standardized test scores. Its municipal services were a national laughing stock. Then, in the summer of 1990, the FBI released the now infamous hotel room video showing then-mayor Marion Barry smoking crack and engaging in an extramarital affair. Americans were understandably aghast when District residents reelected him just four years later.

“For your ordinary white person who doesn’t know anything about what’s going in the city, they say, ‘well, yeah, these corrupt black people are running the government,’” Diner said of the negative headlines that dominated this period in the District’s history. “Which is not unlike what people said when the Irish were running Tammany Hall in the 19th century. I can see that same suspicion — that the city was no longer being governed by competent, educated, professional people.”

The tensions finally came to a head when the GOP seized control of both houses of Congress in the 1994 midterm elections. Republicans arrived in Washington the following January with a mandate to fix the country, starting with a capital city facing insolvency, a deficit approaching $722 million, a ballooning budget, declining municipal services and a dwindling tax base. With Congress holding the city’s purse strings, Barry was forced to relinquish home rule.

“It was a step,” Luci Murphy said of the home rule charter when we finally met face to face at Sankofa Video, Books and Café, a 30-year-old spot on Georgia Avenue just north of Howard University. “Unfortunately, we did not continue stepping.”

Even in her 60s, Murphy, a dry-witted woman who usually dresses in white from head to toe, remains an important presence on D.C.’s social justice scene. It seemed like every five minutes someone was interrupting our conversation to ask how she was doing or if she needed anything.

Longtime D.C. activist Luci Murphy is critical of the city’s post-Civil Rights-era leadership.

Murphy grew up in nearby Columbia Heights surrounded by social activism. Every adult she looked up to — her parents, her pastor, her teachers — was politically involved. Back then activism wasn’t a title or job description. “It was in the air,” she said. “You just breathed it.” She has vivid memories of the days when D.C. schools were segregated. In junior high she spent her Saturdays picketing downtown department stores that refused to hire blacks. As a young woman she was active in the city’s fight for home rule. More recently she’s been involved in its economic justice struggle. The night we met up, she was singing in a benefit for political prisoners.

I asked Murphy what she thought had happened to the nation’s premier majority black city, why it was a fading memory.

“We didn’t get educated,” she answered flatly. “And the so-called leadership was comfortable with people being ignorant because they don’t challenge you the way educated people do. Our leadership was not self-assured enough to take the challenge.”

Murphy wasn’t the first I’d heard lodge such a searing critique of post-Civil Rights-era D.C. Plenty of people — black people — believe what doomed Chocolate City was weak leadership. They count off a litany of issues, from the instances of fraud and embezzlement that have recently tarnished the city council to an ongoing pattern of public sector cronyism and nepotism that began with the home rule era.

“People got jobs but they didn’t get training to do the jobs,” Murphy added. “So they did the job poorly and they didn’t know how to ask for help, because they couldn’t be seen asking. And then you take that money, that check, out to Prince George’s County and abandon the city because TV and magazines and everything is telling you that’s what it’s all about. Big house. Two-car garage. Carport. We lost our way.”

I could appreciate her viewpoint in the abstract: Black people who are unhappy with their shrinking role in the city couldn’t simply blame the federal government or white gentrifiers for taking over the city. The mass black exodus to nearby Prince George’s County had played a role as well. After all, as D.C.’s African-American numbers sank from 536,000 (71 percent) in 1970 to 301,000 (50 percent) in 2010, the county now known as “Ward 9” grew its black population from 91,000 (14 percent) in 1970 to 525,000 (63.5 percent) in 2010.

That said, my own experience coming of age in D.C. three decades after Murphy had given me a different perspective on suburban flight. I grew up in the so-called crack era. I visited friends in jails and hospitals, lost acquaintances to the street life. Between 1990 and 1999 alone, more people were murdered in D.C. — 3,809 — than coalition forces in the War in Afghanistan or U.S. soldiers in combat in Iraq. It was a dangerous time to be young. African-American parents, mine included, saw the suburbs as a safe haven.

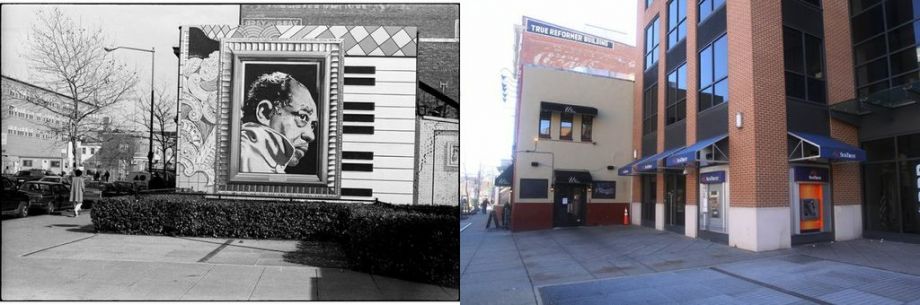

1781 Florida Ave NW, 1999-2000 and present day

Murphy’s perspective also raised an important point about black authenticity and identity that is rarely addressed in Chocolate City lore. D.C. is made up of black communities with distinct histories, philosophies and aspirations. Free blacks made up 15 percent of the District’s population before the Civil War. This generation held solid civil servant, skilled artisan and domestic jobs. After the war, the newly freed flooded the city in search of a better life. It was then that those two “colored” worlds — one typically lighter skinned, acculturated and relatively prosperous, the other, darker, rougher around the edges and typically impoverished — embarked on an uneasy co-existence. Complexion, culture, education and family name have since been significant status markers in the city. The post-Civil Rights-era drove a deeper wedge in those divisions. For some, the whole point of the struggle was the right to movement, sometimes away from the same urban elements that whites left the city to escape. For Murphy, only statehood and the rights that came with it — voting representation in Congress — could have provided the independence D.C. residents were after.

The statehood dream ended when President Clinton appointed a control board to run the city and chaired it with Andrew Brimmer, the first African American to sit on the Federal Reserve Board. Within two years, Brimmer and his bowtie-clad chief financial officer, Anthony Williams, created a budgetary surplus. As a reward, Congress assumed the city’s debts, took responsibility for its courts and prisons, increased the rate for Medicaid reimbursements and relieved some of the city’s pension burdens.

By 2000, the city had been operating in the black for three years running. It had half a billion in the bank and tens of billions in international investment capital beating down its door. Services had improved dramatically. The budding charter school movement was providing a promising alternative to traditional public schools. The MCI Arena (now Verizon Center) had revived the downtown entertainment infrastructure and U Street’s late 1990s resurgence had made the city hip to outsiders again. Congress scaled back the control board and restored Williams, by then the mayor, with much of the authority that his predecessor had been stripped of.

The revival came at a cost, however. Many residents viewed Williams’ administration as an extension of the racially polarizing control board from which he’d risen. A late 1997 Washington Post survey found that while two out of three white Washingtonians approved of the control board, about half of black residents disapproved of it. The discrepancy had logic. En route to balancing the city’s budget, Brimmer had fired several top officials and some 10,000 city workers, the vast majority of whom were African American. He’d pushed through more changes to city laws than in any other period in the District’s history. He’d cut financial supports to low-income residents, slashed unemployment benefits and workers’ compensation, loosened business licensing, environmental and construction regulations and eliminated positions and programs at the University of the District of Columbia, whose student body was predominately African American and low income.

A decade has passed since Williams used his second inaugural speech to publicly court 100,000 new residents by 2010. And while the District’s net growth fell short of his vision, the current racial and class tensions seem uncannily in line with what Rivlin and O’Clereacain forecasted way back in 2001. Which raises the question: If city leaders knew that the path to prosperity was going to be bumpy, why haven’t they helped newcomers understand the touchy terrain and tricky history they are entering? Why haven’t they brought people together to talk about what change means, why it is necessary and how they intend to help residents navigate the path? Why let racial paranoia fester in church basements?

I asked myself these questions during an emotion-filled community discussion I facilitated in Mt. Pleasant in early February. The cozy, tree-lined community of about 12,000 residents sits a stroll from scenic Rock Creek Park, now-urbane Adams Morgan and happening Columbia Heights, home to a spanking new 890,000-square-foot retail space. Forty years ago, Mt. Pleasant was a casualty of white flight. Thirty years ago, tens of thousands of El Salvadorans fleeing civil war began descending on the neighborhood en masse. Twenty years ago, the shooting of a Hispanic immigrant by a black police officer triggered a massive four-day uprising that engulfed the neighborhood. Suddenly, a largely invisible community of, by some estimates, 100,000 was on display. The violence signaled the arrival of a Hispanic community that had sustained its culture through informal networks of power and systems of exchange. The uprising led to the first civil rights inquiry on racial and ethnic tensions in American communities. The 1993 report revealed the widespread mistreatment and neglect that the immigrant community faced. Fast-forward 20 years and Mt. Pleasant is D.C.’s other gentrification story. A neighborhood that was once the Hispanic community’s heart and soul now sits in a super-gentrified zip code, 20010, and has thus been altered beyond recognition.

Sapna Padnya, whom I had met in December, organized the discussion. She proposed gathering a cross section of the community so that I could hear directly from people affected by Mt. Pleasant’s rapid change. An area native who returned from New York a few years ago, Padnya is a bridge between old and new Mt. Pleasant. She and her professor wife are among the new breed who have been able buy into the neighborhood. But the organization she leads, Many Languages One Voice, services the needs of immigrants, many of whom have experienced displacement or the threat of it in recent years.

The two dozen residents who showed up ranged in age from early 20s to late 70s, had lived in the neighborhood for as brief as a year and as long as several decades, and brought a variety of experiences. There was a homeless activist, a one-time Statehood Green Party candidate for mayor, a housing attorney, an African-American woman in her 50s whose family had lived in the city for more than a century, a grad student writing a thesis on gentrification, immigrants from Togo and the Dominican Republic, young people who readily identified themselves as gentrifiers, and a woman who’d been a part of a committee formed to heal the neighborhood after the Mt. Pleasant riots. Even the director of the city’s Office of Latino Affairs stopped in briefly.

A young white woman who’d moved to Adams Morgan after college thought the problem was education and information. A lot of gentrifiers came to D.C. to work for the government. They didn’t known that there was a local history worth learning, as only the federal Washington belonged to the American narrative they learned in school. The African-American woman announced that gentrification was all part of the “plan” and ticked off her evidence like it was a stump speech: Decimation due to white flight, followed by the decline of public services, followed by the introduction of drugs and guns to the community. The woman’s smoking gun: A declassified Nixon quote predicting the unfortunate but unavoidable demise of the black race.

The conversation was on the verge of unraveling when Padnya offered a suggestion. The city currently taxes all income over $40,000 at the same rate. In 2011, the council proposed a temporary 0.5 percent tax hike on incomes $200,000 and above to close a budget shortfall. A poll showed that 85 percent of the city approved of the increase. The bill passed that spring and the bump netted the city nearly $20 million. Creating a permanent progressive tax, Padnya argued, would generate millions in annual revenue that could be earmarked for affordable housing. Padnya’s idea sparked others. Campaign finance reform to dampen the influence of developer dollars was suggested, as was enforcement of the city’s resident hiring requirements. Two months earlier, the fiscal watchdog group, Good Jobs First, released an employment report on D.C.‘s construction industry. The study revealed that despite the existence of a “First Source” law requiring contractors to hire 51 percent D.C. residents on publicly funded projects, and a newer law requiring resident hiring quotas on all non-construction projects receiving more than $5 million in city funds, District residents were still being hired at less than half the rate of workers in the surrounding suburbs. “If District residents participated in construction employment at the same level as the rest of the region,” the report stated, “11,500 more District residents would work in the construction industry, boosting the District’s economy with an estimated $386 million in additional wages.”

My tour through old and new D.C. concluded in a quiet, leafy, upper Northwest neighborhood stocked with handsome Tudors and colonials, manicured front and back yards and streets named after flora. Alexander “Boss” Shepherd, the onetime territorial governor of D.C., built a summer home here in the late 19th century. The neighborhood, bounded by Walter Reed Army Hospital to its south and Silver Spring to its north, has been known as Shepherd Park ever since. Through the 1940s, blacks and Jews had been barred by covenant and custom from living in the neighborhood, but in the late 1950s a cross-racial coalition of residents started a novel experiment for integration. The group called itself Neighbors Inc., and its goal back then was to attract and retain white residents to an increasingly black neighborhood.

Neighbors Inc. tackled an enormous task. It had to challenge institutions and norms that discredited interracial neighborhoods, dispel the myth that black neighborhoods were dirty and woo white residents to living alongside blacks. In the late 1950s it helped end a Washington Post listing policy that steered whites away from certain neighborhoods by labeling them “Colored” if even one black family lived there. In the early 1960s it successfully blocked a city plan to build a freeway through its community and formed a coalition with nearby suburban communities to open up neighborhoods to blacks through voluntary desegregation. After the 1968 uprisings, Neighbors Inc. members played an instrumental role in mending a wounded city.

These efforts created the neighborhood where I was born and raised. Of course, growing up in Shepherd Park, I had no idea ours was an unusual experience. I wasn’t aware of white flight, blockbusting, steering or that the adults in my life — black and white — had fought to preserve the neighborhood so that we could live out the ideals they had all adopted. Integrated classrooms, sports teams, neighborhood manhunt games, cub scout meetings, sleepovers, birthday parties, backyard basketball games and endless summer days trolling the neighborhood looking for mischief — the most ordinary childhood experiences — never registered as anything special to me. Integration wasn’t something I learned in school. It was life.

1214 U Street NW, 1999-2000 and present day

I brought those memories to a party one of my childhood friends was hosting for his uncle’s 75th birthday in his new Shepherd Park home. The house was already bursting at the seams when I walked in. Children were wandering around, the elders, including the still-vigorous guest of honor, were holding court at the dining room table. Everyone else was gliding between rooms, striking up easy conversations. I’d known many of the people in the house for most of my life. They were part of D.C.‘s black middle class — the educated, affluent and connected. The hosts, a corporate executive and his physician wife, had bought the house from a couple who had lived there for 50 years. I had heard and read that Shepherd Park was going through the same racial turnover as the rest of D.C. so I was, admittedly, proud to see one of my good friends putting down roots in my old ‘hood. My family had left Shepherd Park in the early 1990s, but it was still the only neighborhood I’d ever called home.

At some point in the night’s festivities it occurred to me that for all of the fretting about the fate of Chocolate City, a prosperous black D.C. still existed and wasn’t going anywhere anytime soon. The people surrounding me were the ones who could afford to stay and would continue playing a role in the city’s future. The notion that this group would be “ethnically cleansed” failed the smell test. But in order for D.C. not to become strictly a city of “haves,” the imminence of which Mayor Gray warned in his State of the District address in February, a movement like Neighbors Inc. may be in order. Arguably at least, one may have already begun eight miles south and east of Shepherd Park.

They were part of D.C.’s black middle class — the educated, affluent and connected. The hosts, a corporate executive and his physician wife, had bought the house from a couple who’d lived there for 50 years.

Last spring, Gray announced plans to build a charter bus depot in Ivy City, a historically black, working-class community in Northeast D.C. Ivy City has long been regarded an industrial purgatory, housing construction facilities, warehouses and Amtrak’s rail yard. Gray promised that the depot would jumpstart the community’s economy, and indeed it had the potential to do so. With more than 7 million bus riders entering the District each year, it was believed that the depot would produce close to $100,000 in revenue for every 1,000 riders who stayed overnight.

The Ivy City community didn’t take the bait, viewing it was more false hope. Instead, the community wanted to build an adult education and job-training center in the space slated for the depot. It made its desires known, but the city moved forward with its plan anyway. Then, in late July, Empower D.C., a grassroots group with a diverse membership, hired a former ACLU attorney and filed a lawsuit to block construction. The two plaintiffs named in the suit claimed that bus fumes would exacerbate their health problems. Empower D.C.’s lawyers provided strong evidence. It was a shrewd legal play that signaled the evolution of one community’s response to the city’s economic development agenda. Rather than simply protest or kvetch about social injustice in gatherings, the Ivy City community rallied its resources to mount a tactical fight behind a credible and legally recognized grievance suffered by its residents.

And so far, it’s been successful. In December, a Superior Court judge enjoined the city from proceeding with construction until the conclusion of a trial. The victory, however provisional and small in the scheme of things, potentially has significant implications. In the short term, it buys Ivy City time to raise the community awareness, political support and financial resources to realize its alternative vision. More broadly, it serves as a reminder to other disgruntled residents: As important as it is to discuss social injustice in basements, barber shops and street corners, the civil rights movement on which so many still hang their hats required strategy, sacrifice and some really good lawyers.

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Dax-Devlon Ross is the author of five books and has written essays and articles for a range of publications, including Time and the New York Times. He is a non-profit higher-education consultant and the executive director of After-School All-Stars NY-NJ. You can find him at daxdevlonross.com.

_200_200_80_c1.jpg)

Jati Lindsay is a New Jersey born & bred, Washington, D.C.-based freelance photographer. He has been shooting professionally for 11 years. He has been a part of exhibitions at the Leica Gallery in New York City, the Afro American Museum in Philadelphia, the Reginald Lewis Museum in Baltimore, MD, the Corcoran Museum in Washington, D.C. and the Code Gallery in Amsterdam.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine