Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberThe Seattle City Hall ought to have a banner out front reading, “Welcome to Utopia.” Visitors to the LEED Gold structure, which opened in 2003, walk right into the building — no ID check, no metal detectors, no pat-downs — as if in some pre-9/11 fantasy. As visitors gaze out the atrium’s glass curtain wall over the evergreen hills and pristine waters of the Pacific Northwest, they are invisibly enveloped in free public WiFi. If a pang of hunger strikes, the pocket-sized coffee stand hidden away near the grand staircase serves up hormone-free hard-boiled eggs and shots of the perfect espresso for which the city is famous.

The city council hearings, with their near-Scandinavian levels of decorum, order and commitment to democratic procedure, are nearly as perfect as the espresso. A veritable parody of progressive political correctness, the body is like a sketch from the HBO farce Portlandia, or an excerpt from the bestselling spoof, Stuff White People Like. Hardly the puffed-up, grandstanding big-city pols typical of America’s leading cities, Seattle’s representatives are soft-spoken and erudite. All but one — a Pacific Islander — are white.

Though atypical of America, the representatives are representative of Seattle. The prosperous city holds the title as the most educated in the nation and the distinction of being whiter than Wichita, a source of embarrassment to the city’s ubiquitous white liberals. (In Stuff White People Like, “diversity” ranks near the top of the list, beaten out by only a handful of items including “coffee” and “organic food.”)

On July 17, inside the council chamber with its swooping walls of blonde wood and brushed steel, council members were weighing far-reaching changes to one of progressive Seattle’s proudest accomplishments: The New Deal-era Yesler Terrace development, America’s first racially integrated housing project. Stroking their chins, looking overeducated and skeptical, council members pondered whether the Seattle Housing Authority’s ambitious plan to transform the low-rise, low-income public housing project into a high-rise, mixed-income, mixed-use neighborhood truly reached levels of perfection worthy of Seattle.

“Recalcitrant residents who insist on owning cars in the rebuilt neighborhood will have to hide their cars behind buildings and in underground parking lots, like so much dirty laundry.”

A model of transit-oriented sustainable urbanism, plans for the rebuilt Yesler Terrace call for densifying the existing townhome community into a neighborhood that can house eight times its current population on the same 30-acre footprint in buildings up to 300 feet tall. Inspired by recent mixed-use market-rate developments in nearby Portland, Ore. and Vancouver, British Columbia — where environmental-minded zoning has encouraged building taller in the city center to preserve green space on the periphery — the preliminary mock-ups show buildings heavy on glass, surrounded by common space heavy on green. Since private developers would ultimately do the building, the neighborhood will likely end up with plenty of the simple, sleek, earth-toned Japan-dinavian architecture that is popular in the region.

Seattle’s strict Green Factor system, a LEED-like score sheet the city has created and mandated for new development in the city, will ensure that the park-heavy mock-up becomes a reality. The transit element, too, is a fait accompli, not a New Urbanist pipe dream. Construction of a new light-rail line that will link the community to downtown, making it easy for residents who work in the city center to commute car-free, is already underway. As for cycling, city traffic engineers assured the council that bike lanes will be present throughout, and emphasized that bikes will share road with cars only on downhill streets, allowing tired cyclists to take breaks as they ascend the famed First Hill on which Yesler sits. (In the early 20th century, the site earned the nickname “Profanity Hill” in homage to the expletives its gradient elicited from exhausted pedestrians.) Recalcitrant residents who insist on owning cars in the rebuilt neighborhood will have to hide them behind buildings and in underground parking lots, like so much dirty laundry.

Occupying some of the most potentially valuable land in the city, Yesler Terrace is within walking distance of City Hall itself. But just as the steep hill dividing the two sites renders the walk more arduous than it looks on the map, the social distance between the well-to-do white council members and the immigrants of color who constitute most of the project’s tenants may be even larger. For all the meticulous concern over the design of the redevelopment, there is a sense among Yesler residents and many area neighbors that the council is missing the forest for the trees. Critics see council as quite possibly well meaning but hopelessly out of touch, so concerned about the aesthetics and environmental impact of the project, they have lost sight of its social impact — and of safeguarding the public trust itself. In the Seattle Housing Authority’s plans, the 561 units of extremely low-income housing at Yesler Terrace will be rebuilt and more than 1,000 units of low- to medium-income “workforce housing” will be added. But the bulk of the development will be devoted to as many as 3,100 market-rate units.

It is hard to argue that a low-rise neighborhood of townhomes and garden plots is the highest and best use for a plot in the heart of one of America’s most economically dynamic cities. With the towers of downtown Seattle looming over one side of the development and four hospitals abutting another, there are thousands of jobs within walking, cycling and transit distance of Yesler Terrace. The environmental impact of high-income and middle-income workers commuting in from the suburbs, when they’d be perfectly happy to live on a new-and-improved First Hill, is clear.

But the crux of the deal is for the local public housing authority to divest itself of most of Yesler Terrace’s land, selling off the bulk of the project’s footprint to private developers for an estimated $145 million. The SHA insists the divestment is necessary to raise the money it needs to put Yesler residents in better housing. But critics, who pointedly note that the housing authority has never had to open its books to prove its penury, ask why would the public agency charged with building and maintaining the city’s low-income housing want to sell off its crown jewel — especially in a time and place that improbably mixes a high-end residential real estate glut (which has paralyzed the local condo market) with an affordability squeeze for Seattleites of moderate means.

The short list of real estate developers eager to get in on the deal is hardly allaying fears. Recent planning meetings have been attended by representatives of the man who owns Seattle, Microsoft co-founder-turned-real estate magnate Paul Allen, and Forest City Ratner, the famed antagonist in the most contentious community/developer fight of the last decade, the Atlantic Yards’ Battle of Brooklyn. That fight pitted Forest City — a company known for building publicly subsidized developments — against community advocates who said its multibillion plan for a basketball stadium surrounded by a new mixed-income neighborhood of high-rise towers would displace lower-income people.

Lori Mason Curran, spokesperson for Paul Allen’s real estate arm, Vulcan, Inc., refused to discuss Yesler Terrace in even the broadest strokes. But regardless the company’s ultimate role in Yesler, Vulcan and the Seattle Housing Authority are already business partners of a sort; in its divestment fervor, the SHA recently sold off its own headquarters and now rents its offices from Vulcan.

For all the local quirks that make the Yesler redevelopment a uniquely Seattle project, it is in equal parts a federal project shaped by the Obama administration. The neighborhood is one of five to receive funds from the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Choice Neighborhoods program. All five — in Boston, Chicago, New Orleans and San Francisco, in addition to Seattle — are located in what could be called “choice cities,” sought-after places to live for people who can afford their market rates and could choose to live almost anywhere. Specifically, the targeted neighborhoods are places that could all be attractive to well-off professionals — save for the presence of a major public housing project.

Cities that eagerly built public housing in the New Deal and Great Society eras, and then spent the 1970s and ’80s kicking themselves that they were now responsible for presiding over public slums, today find themselves sitting on urban gold mines. But choosing how to deal with their good fortune presents its own slew of new problems, albeit problems they once would have killed for. No city is cashing in its chips with quite as much relish and abandon as Seattle.

The last time plutocrats crashed America’s economy, the man who led Seattle’s emergence from the wreckage was not a plutocrat but a government bureaucrat. The founder of the Seattle Housing Authority, Jesse Epstein, was a salaried city employee who worked out of a one-room office with the assistance of a lone secretary. Born in Russia and raised in Montana, Epstein had moved to Seattle for college and then law school at the University of Washington.

Having the misfortune of graduating as a newly minted attorney into the worst economic downturn the nation had ever seen, Epstein embraced the public-sector social entrepreneurship that typified the nation’s response to the crisis. His move proved well advised. Nearly a decade into the Great Depression, Franklin Roosevelt, having secured a second term, had turned against the premature austerity that had hobbled the nation’s recovery and, in league with progressives in Congress, unleashed a wave of ambitious legislation that included the Housing Act of 1937, which made federal funds available to cities that committed to building public housing.

Following the goings-on in D.C. from the West Coast, Epstein decided he would take up the charge in Seattle. While other cities, most infamously Chicago, would cynically seize on the Housing Act to preserve residential segregation by stacking its burgeoning black population in high-rise towers, Seattle thought differently. Epstein used the opportunity and built the nation’s first racially integrated public housing project.

On First Hill, a neighborhood then dotted with dilapidated apartments and brothels, Epstein built Yesler Terrace as one-third white, one-third black and one-third Asian American. And while other cities encouraged stripped-down, no-frills designs — federal public housing design guidelines had been drawn up in light of a red-baiting scandal that had faulted architects of a short-lived, World War I-era government housing program for “unnecessary excellence” — Epstein signed up top architects and demanded high-quality work. Over cries of socialism (unfair government competition with the private sector) and social engineering (a rogue bureaucrat’s utopian racial integration scheme), Epstein opened Yesler Terrace in 1941.

The development of simple, tidy townhomes with modest, individual garden plots behind was beloved by its residents. It became a rare success story in the generally bleak history of American public housing, boasting an honor role of prestigious alumni. Most notable of them all, Gary Locke, the first Asian-American governor in the lower 48 states and current U.S. Ambassador to China, spent his infant and toddler years at Yesler Terrace.

But as the progressive New Deal era gave way to the conservative Cold War consensus, Yesler Terrace came to be regarded as a problem. Epstein’s bright idea of putting a public housing project on prime real estate in the heart of Seattle began to look like folly. As federal urban planning priorities shifted from affordable housing to linking cities to suburbs via massive expressways, Yesler Terrace provided an easy target. A symbol of the city’ Depression-era past and filled with low-income residents who lacked the political pull to thwart the ravenous public domain machine, Yesler Terrace lost its southwest corner to Interstate 5, which now rumbles along the development’s edge. The freeway connecting Seattle to San Diego swallowed roughly a third of the development’s units.

As federal housing policy changed in response to the failure of projects in other cities, Yesler Terrace, a good example of a troubled form, was an odd fit. The maintenance problems that plagued the most notorious projects in cities like Chicago and Baltimore opened a spigot of federal repair money in the 1970s. At Yesler, the funds were used in an ill-considered renovation to cover the homes in unsightly white siding. “In the 1970s, it was only 30 years old, so we weren’t looking at it so much as historic,” explained Al Levine, a Bronx-born Seattle Housing Authority veteran who now serves as its deputy executive director for development. “We tried to make it what we thought was a modern look at the time.”

The population of Yesler was also changing in those decades. While in many other cities public housing came to be increasingly dominated by native-born African Americans, Yesler became a magnet for international immigrants. Beginning with Vietnamese war refugees, Yesler’s erstwhile native-born Asian-American, African-American and European-American population became a veritable Ellis Island, home to the latest waves of newcomers to Seattle — Somalis, Ethiopians, Chinese.

In the 1970s, Seattle used federal funding for in an ill-concieved renovation at Yesler Terrace that included installing unsightly white siding.

In the 1990s, the Clinton administration launched HOPE VI, a plan to transform public housing projects from low-income projects to mixed-income developments with fewer homes for the poor. Given the booming 1990s economy and the Republican Revolution of 1994, reducing the number of low-income units appealed to a wide swath of the political spectrum. And turning some units into market-rate housing jibed with social science research at the time that showed that poor children do better in school and poor adults do better in the labor market when living in mixed-income neighborhoods. Since HOPE VI targeted the most distressed public housing projects, Yesler — functioning well and having been renovated relatively recently — was passed over by the program while other Seattle projects like Holly Court, High Point and Rainier View were rebuilt as mixed-income communities.

The transformations, many built around new light-rail transit stations and all with appealingly designed market-rate units, appeared remarkably successful, especially during the housing boom of the early 2000s that sent real estate developers and middle-class Seattleites into neighborhoods they’d previously avoided. But Seattle’s public housing tenants smarted at being displaced without a guarantee of a replacement unit on-site.

Hoping to make up for the harshest aspects of HOPE VI, the Obama administration launched Choice Neighborhoods, and chose Seattle’s Yesler Terrace as one of its grantees. While embracing the mixed-income philosophy of HOPE VI, Choice Neighborhoods guarantees one-to-one on-site replacement of all public housing units. And rather than a suburban-style emphasis on replacing troubled high-rise projects with single-family homes and townhouses, Choice Neighborhoods embraces further densification, building higher in order to add market-rate units without eliminating low-income ones. The program also allows housing authorities to modify their project footprints, selling off public land, but also purchasing key parcels in the surrounding neighborhood. The thinking is that no matter how well planned a public housing renovation, even the best will fail if the surrounding neighborhood remains troubled, ramshackle and crime-plagued.

Plenty of social science research backs up the contention that racial and socioeconomic isolation of conventional public housing projects is harmful to the residents they’re supposed to serve. Even though Choice Neighborhoods, unlike HOPE VI, passes the smell test by committing to adding more affluent neighbors without displacing any existing low-income tenants, questions remain. It’s unclear whether the goal of improving the surrounding neighborhood, couched as being in the interests of the poor, really is. If successful on its own terms, more affluent, whiter residents would doubtlessly move into the neighborhoods surrounding the transformed projects, giving a strong governmental assist to recent trends that have pushed poor urbanites into outlying city neighborhoods and suburbs. If Yesler Terrace’s transformation were to whitewash one of the only diverse sections of Seattle through a kind of invisible hand Jim Crow, it would constitute a painfully ironic twist on the site of Jesse Epstein’s black/white/Asian progressive utopia.

Housing authority officials maintain this ambitious transformation is the only way to do right by Yesler’s residents, because Choice Neighborhoods’ modest funding has forced their hand. Even if everything goes according to plan, they note, federal funding will constitute just 10 percent of the total project costs, necessitating divestment and partnering with the private sector to bring the project to fruition over the next decade. (The total Choice Neighborhood funding for all five cities combined is just $122 million.)

“Seattle’s homeless population has repeatedly erected tent encampments on the grassy swath between Yesler Terrace and I-5 — on the very site where low-income housing once stood.”

Yet in the context of the other four cities, the Yesler plans are much grander and much more market-oriented. In Chicago, plans call for replacing the 504 public housing units at Grove Parc Plaza and adding an additional 965 market-rate units. On the housing project footprint in New Orleans’s Iberville, plans call for one-third public housing, one-third low-income housing and one-third market-rate. The Boston project’s emphasis is largely on rebuilding the distressed public housing and improving social services in the neighborhood, using Choice Neighborhoods to create a kind of all-ages Harlem Children’s Zone in down-at-heels Dorchester, rather than a new upscale, high-rise neighborhood. The main development partner is the Dorchester Bay Economic Development Corporation, a local group and hardly Boston’s answer to Vulcan. Even San Francisco’s ambitious plans look like a kind of Yesler Lite, aiming to nearly quintuple the total number of units on the site in contrast to Seattle’s more than tenfold increase.

In the national context, the SHA’s claims that funding the rebuilding of the 561 units of public housing at Yesler required this much divestment has raised eyebrows. “That was always the hardest element for me to discern,” said Councilmember Nick Licata, who holds a masters degree in sociology and calls himself a “skeptic” of the project. “The question [is]: Do you need this much?”

Citing the social success of Yesler Terrace in comparison to so many American public housing projects — a symbol of immigrant hope rather than inner-city hopelessness — project residents and many progressive Seattleites are asking whether it even needs to be demolished and transformed. And, if the land really is so valuable, why not expand the number of low-income units in any renovation? There’s no question about the need: Seattle’s homeless population has repeatedly erected tent encampments on the grassy swath between Yesler Terrace and I-5, on the very site where more low-income housing once stood.

A few hours after the briefing in their perfect building, Seattle’s city council members walked up “Profanity Hill” and got out of their comfort zone. At an on-site hearing at the Yesler Terrace community center, Councilmember Richard Conlin presided, he of the white hair, white goatee, white tennis shoes and white shirt open at the collar (this being the one day of each year when Seattle regrets it has no air-conditioning). A hard-to-quantify admixture of earnestness and condescension pervaded Conlin’s opening paean to the democratic process. “Public hearings are an important part of democracy,” he intoned, “and one of the things about democracy is being respectful of each other’s points of view.” Conlin’s grade-school-level lecture instructing Yesler’s residents, most raised in developing world dictatorships, in the ways of American democracy bore a distinct whiff of the “white man’s burden.”

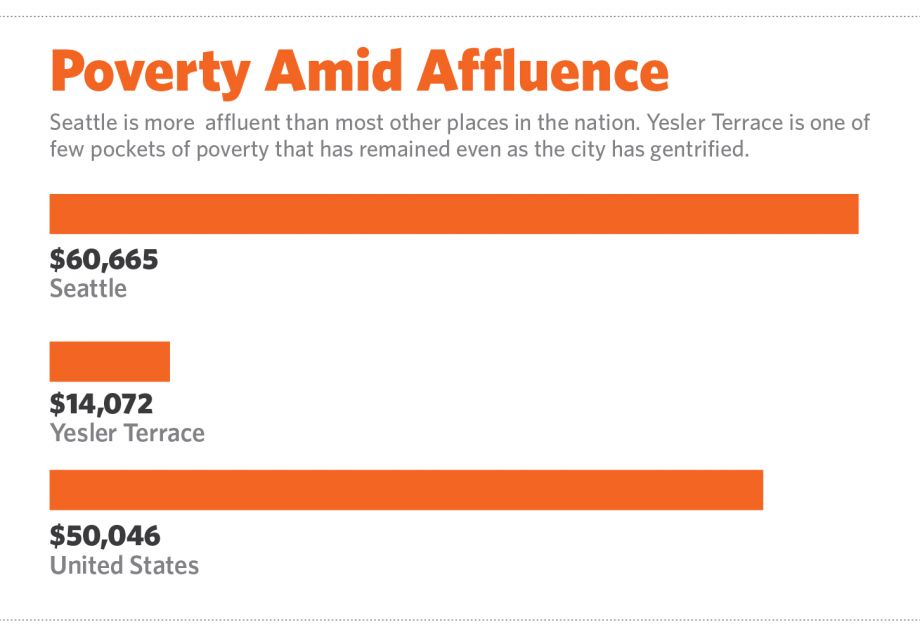

The vast majority of residents in today’s Yesler Terrace are foreign-born; racially, the development is 44 percent black, 42 percent Asian, 11 percent white and 3 percent Native American. Yesler residents have an average annual household income of just under $14,000. By contrast, the area median income for a household of just one person in the Seattle region is a whopping $61,600. (Seattle City Council members all pull down six figures, making them the second-highest paid city council members in the country after Los Angeles.)

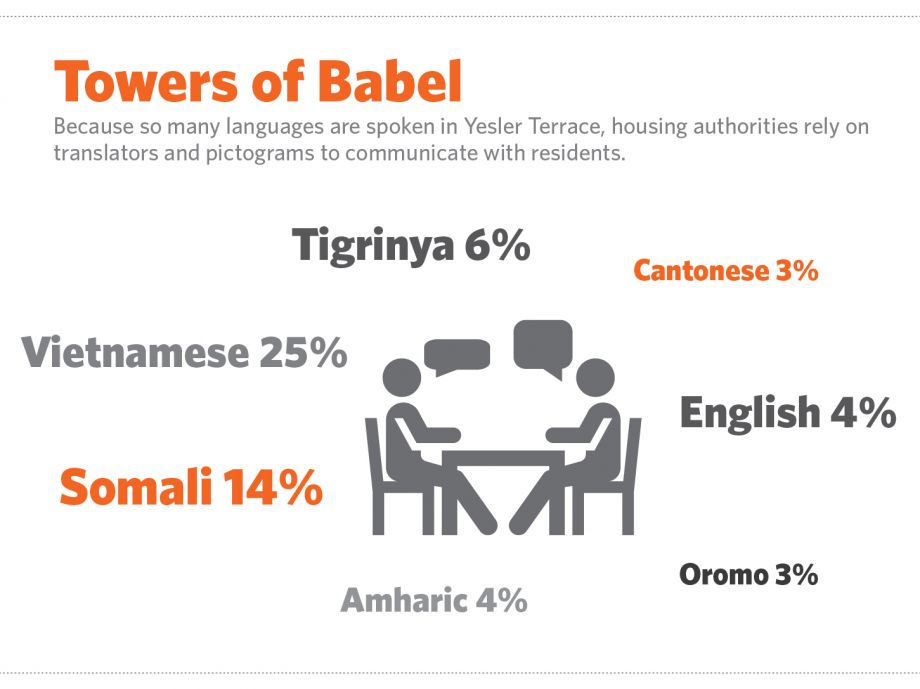

Just to make the diverse Yesler development function, the SHA employs translators for the four most popular languages in the project — Vietnamese and the East African tongues of Somali, Amharic and Tigrinya. For those who don’t speak any of those languages or English, well-meaning facilities managers use a picture book to figure out what part of an apartment needs repair.

For all the self-regarding earnestness of the housing authority, displacement is unpopular among the residents. Even middle-class homeowners and renters have things they don’t like about their house or apartment — but very few improvements are worth the trade-off of several months of moving out. This basic fact seems lost on Judy Carter, the matronly, on-site facilities manager at Yesler. As Carter proudly explained, she has given residents 18 months’ notice that they may have to move out. “I think we’re only required to give 90 days,” she said, “[so] that’s the Seattle Housing Authority being miraculously nice and wonderful!”

In advance of the hearing, then-SHA spokesperson Virginia Felton predicted bluntly, “the public hearing will be a circus.” Indeed, famed anti-gentrification activist Babylonia Aivaz was present — though minus her trademark white wedding dress. Aivaz vowed to “marry” her beloved Yesler Terrace in a street-theater ceremony and invited the council members to her upcoming nuptials by presenting them each with a leaf of organic chard grown in a nearby community garden threatened by the redevelopment plans.

Most speakers were less dramatic but no less passionate than Aivaz. The petite, white-haired Genoa Caldwell of Citizens Rethink Yesler (CRY) urged the council to preserve, and even expand, “Seattle’s Ellis Island” rather than “provid[ing] penthouses for the 1 percent.” CRY has urged the housing authority to consider leasing part of the land for private development rather than divesting itself of so much publicly owned prime real estate. Another white liberal activist, who appeared with her middle school-aged son and his Asian American best friend in tow, exhorted the Seattle Housing Authority to “go back to your mission statement,” which focuses exclusively on housing the poor.

This echoed the view of Aimee Schantz, a middle-class professional employed by the University of Washington who had bought into a nearby condominium building for just over $200,000 before the boom. “We have a wonderful and beautiful community exactly as it is now,” Schantz told the council at a prior hearing. What the housing authority had packaged as an appealing new “mixed-income neighborhood” was to her a troubling and unwanted new “income disparity.”

“Levine’s vision of a hyper-gentrified techopolis is precisely the one the anti-gentrification activists pushing back against the Yesler Terrace renovation plans are trying to thwart.”

Residents and business owners in Little Saigon, the informal name for the neighborhood bordering Yesler Terrace to the south, were apprehensive as well. In the pedestrian-oriented hill-climb the housing authority was touting as a way for new, well-heeled customers to access their restaurants and markets, they saw the floodgates of a wave of gentrification that could wash them away. American-born Yin Lam, who has worked in her family’s business, Lam’s Seafood, for 20 years, said it was by working behind the checkout counter that she learned her ancestral language and culture. Where, she wonders, will her newborn learn about his roots if the Little Saigon strip just south of Yesler Terrace becomes just another stretch of coffee shops and cocktail lounges catering to the technorati? Another Vietnamese merchant affiliated with the group Save Our Little Saigon pointed out the irony that catering to the employees of successful start-ups-turned-behemoths like Microsoft and Amazon could stamp out an island of entrepreneurship in the heart of the city: “Without affordability in Little Saigon, we won’t be able to incubate small businesses.”

While on their face, the strip malls dotting Little Saigon may not appear to be a particularly good use of such a well-located plot of land, residents and businesspeople implored their city council to value urban space as more than just real estate. Isn’t there value in a place where immigrants can find economic opportunity and transmit their ancestral culture to the next generation, even if the parking lot-pocked enclave wouldn’t fare well on a LEED or Green Factor scoring checklist — or a property developer’s balance sheet?

Though outnumbered and overshadowed by their better-off neighbors, the public housing residents of Yesler Terrace lined up to speak as well. But the power of their voices was often lost in translation or diminished by their broken English. Fatima Isaq, who has lived at Yesler for nearly 14 years but whose headscarf bore the stamp of her native Ethiopia, plaintively implored the panel, “I hope you guys to hear our voice.” Whatever the good intentions of the white, native-born, overwhelmingly male city council members, seeing beyond her race, gender, religion, national origin and language barrier would surely be a tall order.

And good intentions ought not necessarily be assumed. Before the meeting, SHA development executive Al Levine, who, with his unreconstructed New York accent, relishes playing the role of hardnosed realist on the airy-fairy Left Coast, said he expected “every crazy in Seattle” to show up. Afterwards, he reported that four different members of the city council had confided to him, relieved that the hearing “wasn’t so bad.”

At a public hearing on redeveloping Yesler Terrace, residents and neighbors spoke out against a project that they fear will displace tenants without guaranteeing on-site replacement.

In part, this was because many of Yesler’s immigrant residents didn’t even show up. Some, like Peter Le, a refugee from Vietnam who has lived at Yesler for three years, spent the time tending the gardens in their townhouse yards. Oblivious to the hearing, Le was enjoying precisely the type of amenity slated for elimination by the renovations.

White, native-born resident Kristin O’Donnell, who has lived at Yesler for nearly four decades and leads its official resident organization — a combative community group funded by the Seattle Housing Authority as part of its commitment to by-the-book democratic process — showed up, but didn’t put much stock in the hearing. Wearing her trademark Felix the Cat watch, she offered her bleak assessment: “Congress thinks public housing is a failed experiment, so we’re toast.”

Seven weeks after the on-site hearing, the Seattle City Council voted unanimously to approve the transformation plan, albeit with a few additional requirements. Councilmember Licata said that with the financial and environmental arguments for density proving an unassailable proposition for the rest of council, he ultimately came around because “we got a number of safety checks.” One calls for the SHA to explore leasing rather than selling off so much land, as CRY endorsed. The authorization also requires the SHA to explore creating low-income housing, affordable commercial space and a cultural center in Little Saigon with neighborhood representatives. Because of Choice Neighborhoods’ funding flexibility, the SHA could theoretically use Yesler redevelopment funds in Little Saigon.

With its high-rise scheme now approved, Seattle’s Yesler Terrace is again in a class by itself. The SHA’s ambitions today are as outsized as they were at its founding. They’re just directed toward a very different vision.

Touring the housing authority’s completed HOPE VI projects with Levine, it is evident that the SHA’s perfect plans invariably lose some of their grandeur in becoming realities. At Rainier View, tight transit budgets precluded building as many light-rail stations as housing authority planners had hoped for. And community opposition held down height limits on the Scandinavian Modern-style apartments abutting the stations — precisely where transit-oriented development gospel would endorse building tall. “Seattle is famous for its process,” Levine said by way of explanation; “process,” in his book, being a euphemism for too many cooks spoiling the soup rather than a synonym for deliberative, participatory democracy.

It is not just Seattle’s unpredictable “process,” but also the erratic economy of the last decade that has upset the apple cart. Case in point: Before the crash, the SHA’s High Point redevelopment was slated to have a Whole Foods; now it’s supposed to get a Trader Joe’s. But for those who bought into HOPE VI communities, the stakes are significantly higher than simply the price and quality of their organic produce. Circa 2000, Seattle’s HOPE VI projects were selling market-rate homes for $170,000. At the height of the boom, they topped out at $600,000. Middle-class buyers who got in early struck gold; those who jumped in too late wrecked their financial lives. “Unfortunately,” admitted Levine, “there are some buyers who found themselves underwater.”

The crash also hamstrung the Seattle Housing Authority’s grand, market-reliant blueprints for its complete master planned communities. Several times on the tour, Levine pointed out vacant lots, large parcels that had once been owned by the housing authority but had been sold off to developers who fell victim to the downturn. “This builder went bankrupt on us,” Levine said, passing one. “That builder went belly-up and stopped construction,” he offered, driving by another.

Still, Levine remains optimistic that the SHA’s vision for Yesler — and his larger personal vision for the city — will ultimately come to fruition. Driving past the Starbucks world headquarters on the way back to the SHA’s rented offices, Levine daydreamed about the future of his adopted hometown. “I think Seattle’s going to be like San Francisco in 20 years. It’s going to be that desirable a place, in spite of all of this process stuff.”

Levine’s vision of a hyper-gentrified techopolis is precisely the one the anti-gentrification activists pushing back against the Yesler Terrace renovation are trying to thwart. Ironically, the activists see themselves as fighting for the SHA’s original vision, the one described in its mission statement. They believe they are safeguarding Jesse Epstein’s vision of an affordable, diverse, harmonious, humane Seattle from a rogue incarnation of the very institution he created, a kind of bureaucratic Frankenstein.

But the forces shaping Yesler Terrace are larger than the SHA, its tenants, the City Council or even the 620,000 active citizens who call Seattle home. It was the progressive federal framework set up in response to the lessons of the Great Depression that birthed the original Yesler Terrace. Choice Neighborhoods appears not to have gleaned any such lessons from the Great Recession. The HUD program betrays a faith in the market untempered by the collapse of 2008 and an unstated assumption that no matter how prosperous a city becomes, it will never use its resources to expand public housing for its poorest residents.

Of course, it was not until 1937, fully eight years after the crash and five years into FDR’s presidency, that the Housing Act passed. Only a far more audacious policy than Choice Neighborhoods will allow the next Jesse Epstein to emerge. In the meantime, the Seattle Housing Authority’s current rehabilitation plans call for the Jesse Epstein Building at Yesler Terrace, a redbrick edifice filled with non-profit offices, to be demolished.

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Daniel Brook has published on urbanization in India in The New York Times Magazine, Slate, and The Baffler and in his book, A History of Future Cities, which is now out in paperback from W. W. Norton.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine