Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

The Springfield Avenue Pumping Station doesn’t look like much. The squat pile of bricks with a tall smokestack is tucked at the end of a residential street on Chicago’s northwest side. A cloud of steam rising from the roof is the only clue to what goes on behind its steel door. It looks like any functional city building anywhere.

But this drab outpost of Chicago’s municipal water system could be the start of a new way cities pay for the things that make them run. The Springfield Avenue station is one of four water stations in Chicago still powered by steam and natural gas. It has run that way for decades, and it’s expensive. City officials want to convert it to more efficient electric power. But that’s a $73 million project, and cash is tight these days. So they’re taking the station out into the market, offering private investors a piece of the action.

Governments across Europe, Canada and Australia have long turned to the private sector to help finance public assets, and even in the U.S., more places are dabbling in it. But it’s still rare for cities to take the lead. And no place, at least in this country, has tried what Chicago is launching this year: A non-profit agency devoted to tapping private capital through structured financing while retaining public ownership, both for big-ticket items but also for workaday municipal infrastructure.

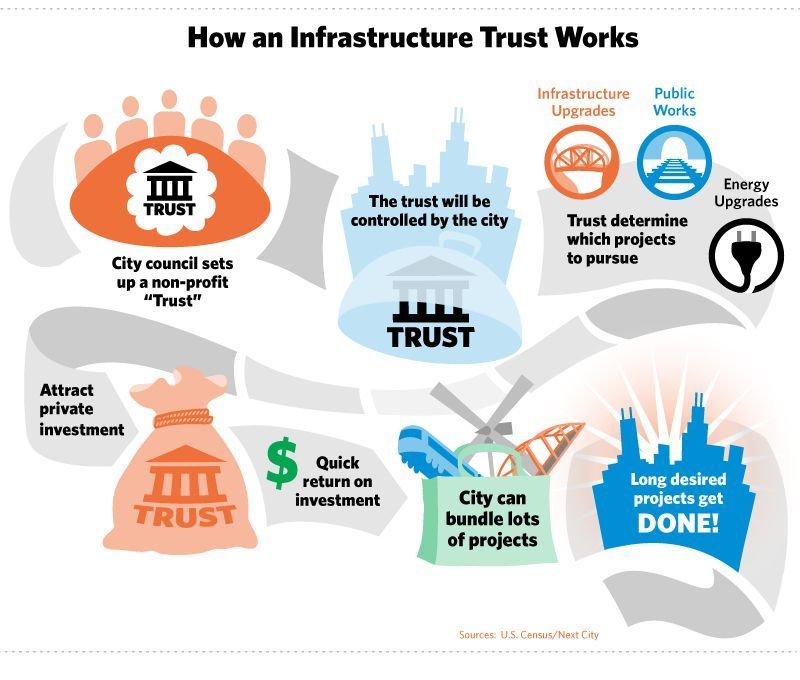

With Bill Clinton by his side, Mayor Rahm Emanuel last March announced the creation of the Chicago Infrastructure Trust, a non-profit agency that would manage private investment in public works projects. The Trust, Emanuel said, would be a way for Chicago to pay for the improvements it needs to stay vibrant.

“We have a 21st-century economy sitting on a 20th-century foundation,” he said at the news conference announcing the Trust. “Unless we modernize it, we ain’t going to get moving.”

A lot of people are watching what’s going on in Chicago, and if the “City That Works” can make this work, it could hold the key to an evolution in public-private partnerships — and the way our cities get built.

“America as a country has grown to expect infrastructure to fall from the sky. But it’s not anymore.”

The nation’s bones are getting old. From roads and rails to river dams to water pumps, many of the systems that help states and cities function are reaching the end of their useful lives. In March, the American Society of Civil Engineers gave the nation’s infrastructure a grade of D+ and projected $3.6 trillion in spending needs by the end of the decade to bring it up to acceptable levels. And there’s growing concern about the need to not just maintain existing systems, but to upgrade them to make cities more resilient in the face of climate change and extreme weather events like Hurricane Sandy.

The Civil Engineers’ D+ grade was actually an improvement from a D in 2009. The small but significant vote of confidence came about in large part as a result of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, which sent billions of dollars to local projects for road repairs and infrastructure modernizations. But now ARRA is over, and Washington gridlock of the last few years has tightened the federal tap. This has states and cities searching for their own ways to pay for things, from revolving loan funds for sewer work in New York to a transportation sales tax proposed in Missouri.

Regions all over the country are going to have to think differently about how they pay for infrastructure needs, said Peter Skosey, executive vice president of Chicago’s Metropolitan Planning Council and one of the city’s leading experts on transportation. The old favorites of federal grants and municipal bonds simply aren’t enough; money from the gas tax isn’t what it used to be.

“We have to be open to new approaches,” Skosey said. “America as a country has grown to expect infrastructure to fall from the sky. But it’s not anymore.”

Increasingly, those new approaches include private money. And not just through traditional municipal bonds, but also through deals that give investors a direct revenue stream in exchange for cash on the table. A few states are opening offices to help manage public-private partnerships — perhaps the most advanced is in Virginia, which recently opened 14 miles of privately funded toll lanes on I-495 in the D.C. suburbs — and others are mulling legislation to create their own. President Obama has repeatedly called for a national infrastructure bank that would pool billions of dollars in private capital to lend on projects, though Congress has been skeptical.

In some parts of the world, this is old hat. Some European nations have long sought private investment in infrastructure. The United Kingdom privatized most of its airports in the 1980s — to mixed success, some now say — and prominent roadways in Canada and Australia are privately operated. A number of countries have dedicated government agencies that manage and monitor public-private partnerships, and protect the public side of the deal.

For many reasons, the U.S. has been slower to develop P3s. State-level PPP offices are mostly still in the incubation stage, and 17 states have not even passed legislation to enable public-private partnerships for transportation projects, according to the Federal Highway Administration.

From 1985 through 2011, less than 10 percent of all the P3 investment in the world had taken place in the United States, according to Brookings Institution, a D.C.-based think tank that has recommended the federal government establish an office to encourage more of these public-private collaborations.

Many projects undertaken so far have been comparatively old school, trading long-term control of a toll road or city water system in exchange for cash up front. They’re big deals, clunky and often controversial, and no one has quite figured out how to make them easy enough to fund the kind of small projects that cities sorely need.

That’s why people are watching Chicago’s Trust so closely, said Patrick Sabol, a senior researcher who studies infrastructure at Brookings’ Metropolitan Policy Program. His team fields at least one call a week from a city or state looking for ways to better tap private funds for their public needs. But most lack the resources, or the know-how, to set up their own infrastructure bank. Chicago — which is spending millions of dollars on lawyers and consultants to devise the Trust — is essentially drawing a road map.

“Even if the Chicago Infrastructure Trust doesn’t thrive in the way we hope it will, they’re setting up the legal aspects, the project criteria, all the process,” Sabol said. “Other people can replicate it. That’s huge.”

And Chicago is drawing that map as it drives.

The nation’s third-biggest city has long been a pioneer in partnering with the private sector. In 2005 the city leased its Skyway toll bridge to a consortium of private investors for $1.8 billion. It has turned over downtown parking garages and meters citywide to private operators for cash. Its law firms, and its city hall, are stocked with people who’ve played this game before.

Now, with the Infrastructure Trust, they’re trying to take it to the next level.

The Trust, which passed the City Council last spring, is set up as a non-profit entity, with a board that mixes public- and private-sector heavyweights and a full-time executive director. Unlike some of the state-level offices that focus more on planning, it will design and negotiate financial deals with private investors, not just the bureaucratic needs of making public works projects go.

And, in an important distinction from many big P3 projects of old, Emanuel insists that any city projects funded through the Trust will remain under city control. There will be no asset sales or lifetime-long leases. The whole thing is designed to attract private money and pay it back relatively fast — say, in 10 years instead of 90 — so that the city too can profit from the improvements that get made.

The Trust is also designed to shift risk away from taxpayers and put in on the backs of private investors, said Lois Scott, Chicago’s chief financial officer and one of the Trust’s main architects.

Take its first project: $101 million worth of energy retrofits in city-owned buildings. The Trust is seeking cash up front from investors, to be paid back over time with the money saved from those improvements. The city has plotted out what it thinks those upgrades will save in lower energy costs, but unlike a general obligation bond, for instance, it’s making no guarantee on the return. Indeed, in a document soliciting partners for the retrofit project, the Trust states in big capital letters: “REPAYMENT FOR INVESTORS WILL BE FROM OPERATING BUDGET SAVINGS ONLY.”

In other words, if energy costs climb and there’s no payback, it’s the investors, not the city, who lose out.

“That’s on their backs,” Scott said. “They know how to handle risk, how to price it. Governments don’t take risk like that.”

There’s another key difference from the way private sector involvement has typically worked in the past. Instead of funding just one big, discrete project like a toll road, the Trust will enable the city to bundle lots of small ones — those energy upgrades will be on dozens of buildings — and sell them to the market in one transaction. It’s a lot more efficient that way, Scott said, and it means these long-desired projects can actually get done.

“You can’t do 300 discrete energy retrofit projects through the private markets. The transaction costs are too high,” she said. “But if you bundle them, you can raise money efficiently.”

“They’re creating this pipeline of projects and that brings the money from the market. If you create the pipeline, the money will follow.”

It’s a smart idea, said Xavier de Souza Briggs, a planning professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who spent the first two years of the Obama administration as associate director of the White House Office of Management and Budget. It’s not unlike the structured finance approach of bundling lots of home mortgages and selling them to investors — though hopefully, Briggs noted, without crashing the economy the way subprime mortgages did. It’s a way to bring big money to relatively small assets.

“The key to pooling these projects is standardizing them,” Briggs said. “If you can make the buyer of the paper trust that the underwriting is secure, then they don’t have to sweat each individual building.”

That combination of attributes makes the Trust attractive to some big investors like Jeff Murphy, managing director of the Infrastructure Investments Group at ULLICO.

Murphy’s firm, which manages life insurance and investments for labor unions, sees a lot of potential in infrastructure investment. It has long put money into commercial real estate, but hired Murphy in 2009 as part of a team to work on infrastructure deals. It closed its first in December, taking an equity stake in a California city water system.

ULLICO was one of five big institutional investors — among them Australian infrastructure giant Macquarie and big investment banks J.P. Morgan and Citi — that agreed last spring to look closely at Trust projects.

To Murphy, the way the Trust is set up gives it more appeal to investors who have a world of choices for where to put their money. That higher risk that projects like the energy retrofits carry means they also carry a higher return than traditional municipal bond projects. And by organizing and bundling projects and then marketing them to investors with a clear payback, the Trust can move quicker than in an infrastructure “bank,” where funds are gathered first and then projects found. It makes for a simpler, cleaner transaction.

“They’re creating this pipeline of projects and that brings the money from the markets,” Murphy said. “If you create the pipeline, the money will follow.”

It had better, for Chicago’s needs are massive.

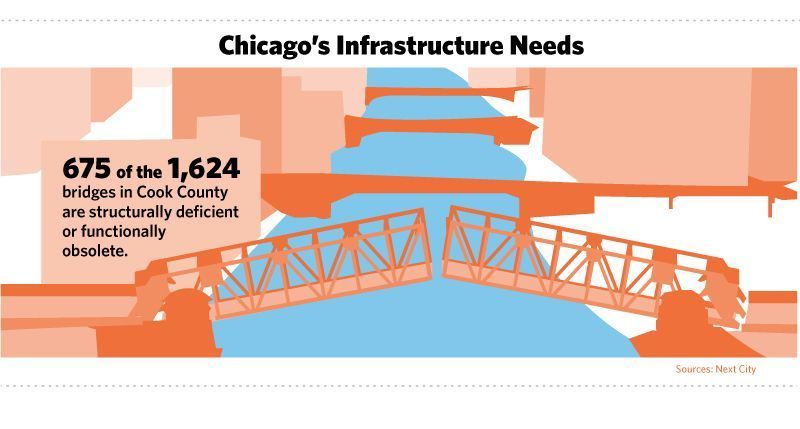

Today, the U.S. Department of Transportation deems 675 of the 1,624 bridges in Cook County to be structurally deficient or functionally obsolete. The Regional Transit Authority in 2010 studied every rail car on Chicago’s famous ‘L’ and its commuter rail system, finding that four in 10 were beyond the end of their useful life. Roads and water treatment plants need work.

Late last year, the Institute for Illinois’ Fiscal Sustainability tallied up all the reports and found more than $340 billion in infrastructure needs across the state. The trouble is, there’s nowhere near $340 billion to pay for them. By most measures, Illinois is broke.

The state has a long history of running budget deficits, and a $9 billion pile of unpaid bills last year means that checks to state Medicaid providers and other contractors routinely run late. Unfunded pension liabilities topped $97 billion at the end of 2012. That number grows by $17 million per day.

This has made even traditional bonding quite costly. In January, Illinois’ 10-year bonds were selling for a full percentage point above even those of California, according an analysis of Thomson Reuters data. And after rating agency S&P downgraded Illinois’ credit debt in January, state officials delayed for three months a $500 million bond sale for fear that interest costs would spike even higher. Though these fears were allayed when the bond sale took place in April, the postponement delayed school and road projects under a program called Illinois Jobs Now!.

All this has pushed Emanuel to take matters into his own hands, said Laurence Msall, president of The Civic Federation, a Chicago-based research organization. If the feds and the state can’t pay for Chicago’s needs, the city will.

Of course, the city itself doesn’t have much money, either. Its recommended capital budget for 2013 is $1.6 billion — which, after deducting for airport improvements, leaves less than $1 billion for general projects. It already owes $20.2 billion in long-term debt. It pays $1.55 billion a year in interest alone, a sum that’s up one-third since 2008. Looming on the horizon are big jumps in pension costs for police and firefighters.

“Chicago already has a relatively high level of debt per capita,” Msall said. “Without identifying a new revenue stream, it’ll be difficult for the city to launch a major borrowing program for infrastructure or anything else.”

So rather than borrow, the city is hoping to build a new revenue stream to pay back investors over time, with the savings from projects like retrofitting the Springfield Avenue Pumping Station.

The station was last refurbished in the 1950s and its power system requires two steam boilers to be running full-speed at all times. Energy alone cost $2.1 million in 2011. The city hopes to knock that bill down by switching to an electric-powered variable-speed drive, which would give the system just the power it needs at any given time.

“It’s kind of like a dimmer on a light switch,” Water Management Commissioner Tom Powers told the Infrastructure Trust board during a presentation in December. “You can turn it up or off.”

That switch alone will save nearly $1 million a year, Powers said, and getting rid of those ancient boilers should save another $500,000 in maintenance. But the biggest savings will come from manpower. Keeping this 60-year-old system running requires 33 people working in shifts around the clock behind those steel doors. After the upgrades, Powers said, Springfield Ave. will need six — though he was quick to say those workers wouldn’t be laid off, but moved to other posts in the Water Department and their jobs reduced via attrition.

“The goal of the Springfield Avenue Pumping Station is basically reduction,” Powers said. “It’s reduction of energy. It’s reduction of manpower. Reduction of ongoing maintenance.”

All that reduction will save Chicago an estimated $4.5 million a year. When the debt is paid back to investors, the city has a good-as-new pumping station with decades of life ahead of it.

The job, and the dozens more bundled with it, appears to have drawn a lot of interest from the market. In late January the Trust put out a request for qualifications — essentially statements of interest from companies that might want to invest — for its $101 million first round of projects. When the responses were due six weeks later, it received 14, ranging from financial-industry giants, such as Wells Fargo and U.S. Bank, to boutique investment banks and green-energy specialists.

Now Trust officials will vet those responses and put together a pool of potential investors. From there, they’ll seek specific proposals and negotiate a deal with one or more, before submitting it to the City Council and Board of Education for final approval. They’re hoping to have a deal closed by summer.

The man negotiating these deals will be Stephen Beitler, a retired Army lieutenant colonel turned venture capitalist who signed on in February to become the Trust’s executive director.

City officials declined several requests to make Beitler available for an interview, but he told the Chicago Tribune upon taking the job that he plans to closely study public-private partnership models in places like Canada, Europe and India. And he pledged that his primary goal would be to cut deals that benefit the city and its taxpayers.

“I suspect there are ways to reduce the city’s operating costs through public-private partnerships… in manners that are consistent with what the people of the city of Chicago would want,” he told the Tribune.

That can be done, said Joseph Schofer, who heads the Infrastructure Technology Institute at Northwestern University. But it requires an open, transparent process to build trust, and the patience to make sure everyone fully understands the deal. It also means understanding that the guy across the table with the deep pockets has one main priority, and it’s not fixing Chicago’s infrastructure.

“He damn well wants to get that return,” Schofer said. “There’s no free money.”

Chicago has learned that lesson the hard way.

These days in the city, a shadow hangs over any public-private deal that gets proposed. It’s in the shape of a parking meter.

In 2008, in a deal pushed through the City Council in a few days, then-mayor Richard Daley leased the city’s nearly 36,000 parking meters for 75 years to a group of investors led by Morgan Stanley. The $1.16 billion payment helped plug holes in the city’s budget, and Chicago streets now sport new, energy-efficient meter boxes.

But in 2009, Chicago’s inspector general issued a report saying the deal had undervalued the city’s meters by nearly half. Thanks to five straight annual rate increases that were part of the contract, it now costs $6.50 an hour to park on the street downtown. And the private operator, known as Chicago Parking Meters LLC, says City Hall owes it $61 million for lost revenue from street closures. Parking privatization has proven costly in other ways, too. In March, the company that operates four downtown garages won a $58 million judgment from the city in a lawsuit against a decision by the Daley administration to let another garage open nearby.

The Emanuel administration says it doesn’t like these deals any more than anyone else, and has been in court fighting those bills from the street closures and the garage lawsuit. Scott said she and other city officials have learned some valuable lessons, and they’re determined not to make the same mistakes twice.

City aldermen learned a lesson, too, and several pushed for better oversight and transparency when the Trust came before them for approval last spring. Now any Trust deals on city-owned property will need votes by both the City Council and the Trust board, and will be subject to review by the inspector general.

Still, there are a lot of skeptics out there, like Tom Tresser.

The civic activist — he led the local campaign against Chicago’s bid for the 2016 Olympics — looks at the Trust and sees the latest in a long line of giveaways by city government. Why can’t Chicago fix its own water systems, he wonders, or run its own toll roads, and invest money it saves in other needs like schools? If the city is broke, Tresser argues, it’s because of poor choices in the past: Everything from overgenerous pensions to widespread use of tax increment financing. More of the same won’t help.

The problem, he said, is that these deals are designed so that the private sector gets paid, when there’s no good reason why the public sector shouldn’t see the proceeds instead. He cites a study on the parking meter deal suggesting that, in the end, Morgan Stanley will get back 10 times what it spent on the lease.

“Even if the return on capital winds up being four for one, or five for one,” he said, “Why can’t we get that?”

Instead, Tresser said, the profits go to private investors, and to the army of consultants and bankers who manage the deals, while the city struggles to pay its bills. That’s the way public-private partnerships have always worked in Chicago, he said, and — while he called Lois Scott “one of the smartest people I know” — he’s got little faith that the current regime in City Hall will fare any better in these deals than its predecessors.

“I don’t trust the people in charge,” Tresser said. “They got us into this.”

Scott said the city has learned from these mistakes. That’s why it’s so focused on writing deals that transfer risk to private operators. But city officials can’t stick their head in the sand, she said. They need the resources that public-private partnerships can bring if they hope to keep Chicago competitive in a global economy.

“This is about building long-term capacity,” Scott said. “[In the parking meter deal], the motivation got confused with the tool. The tool has worked well for us in other deals.”

And Chicago is likely to see more private investment in the public sector, even aside from the Infrastructure Trust.

In December, City Council approved a plan to lease city-owned land along highways to an advertising company for digital billboards. A citywide curbside recycling program will launch this year, with private operators. And this summer, the fare system on Chicago Transit Authority buses and trains will switch over to a private operator, which will introduce a debit card system in exchange for a tiny slice of the fare for each swipe.

The CTA is considering a deal that will be even more visible, having hired Goldman Sachs to look at public-private partnerships for a big rehab and expansion of its Red Line. The project, which would push ‘L’ service five miles deeper into the city’s South Side, would cost an estimated $1.5 billion. And while the CTA doesn’t plan to privatize operation of the trains, it is mulling a partnership to design, build, finance and maintain the line. They’re hoping to save 10 or 20 percent of the cost, which would mean starting faster.

While no specific deal has been proposed, the idea has received “overwhelmingly enthusiastic” response in early conversations with financiers, CTA President Forrest Claypool said in January.

There’s an even bigger deal on the table a few miles west of the Red Line, at Midway Airport. The city first tried to privatize its second airport under Mayor Daley, but the weak economy in 2009 scuttled a $2.5 billion proposal. Now the city is shopping Midway once again, hoping to use the proceeds to fund other infrastructure needs. In February, it received 16 letters of interest, and city officials could seek proposals for a deal and submit a plan to aldermen as soon as this summer.

For Midway, in what’s widely seen as a nod to misgivings about the parking meter deal, Emanuel appointed a seven-member committee to monitor the process and “ensure transparency and integrity.” It will issue reports to the public and to City Council before any vote is taken, and is charged with making sure the public’s interest is protected.

“It’s the first time I know of that anything like this has been tried,” said Peter Skosey, the committee’s co-chairman. “We want to make sure we’re as accountable as possible.”

Skosey, at the Metropolitan Planning Council, knows a lot about Chicago’s infrastructure needs. Besides chairing the Midway panel, he is one of the region’s leading authorities on transportation, and his Loop office is filled with thick studies and big plans — Chicago, after all, is a town that makes no small ones.

His shelves are covered with bound brochures on bus rapid transit and four-pagers on a redo of Union Station. Under his desk is a hefty copy of something called GoTo 2040, a 30-year joint transportation and land use plan, the first of its kind in Chicago.

Skosey pulls this out and starts leafing through the recommendations. There are dozens, and in all they would cost $380 billion over three decades.

The top five priorities — what Skosey called “a manageable, realistic list of projects,” including the Red Line Extension and a new bypass connecting O’Hare International Airport and the far western suburbs — would run $10 billion. Even with revenue streams like tolls on that new bypass, the money just isn’t there.

Finding it, Skosey said, is going to require a team effort, a mix of public and private, with creative approaches on both sides. That’s largely how the system to develop subsidized housing has evolved, and it’s likely how infrastructure will go too, he predicted

“The bottom line is that every infrastructure deal starts to look like a layer cake,” he said. “It’s not just going to be 80 percent from the feds, 20 percent from the state.”

“There’s this big world of capital out there and city governments have always focused on just this little slice of it.”

That’s the way it’s working with the Trust already. Chicago has started the first phases of its energy retrofit projects with money raised via more traditional measures. The cash it attracts from private investors will go toward finishing the job, albeit faster and with more left over for other projects. Scott says she expects the Trust will regularly blend private and public capital, and it was formed as a non-profit in part so it could tap foundation grants and other money that doesn’t typically flow to infrastructure.

“We don’t always have to just go out and get federal grants and issue municipal bonds,” she said. “There’s this big world of capital out there and city governments have always focused on just this little slice of it.”

Chicago officials have said little about what sort of projects, exactly, they plan to run through the Trust once they get the initial retrofitting job under their belt. It clearly won’t work for everything — it’s hard to imagine Citibank investing in basic street maintenance, for instance. But the idea is to create a structure that’s flexible enough to work for a wide range of needs. It’s quite possible, said Brookings’ Sabol, that the Trust will evolve into a vehicle for finding the last chunk of funding on a road project, or for relatively modest real estate deals, as opposed to just focusing on multibillion-dollar behemoths.

“It seems like the Trust is carved out to do discrete projects that have a clear return on investment,” he said. “The kind of things where $100 million can make a real difference.”

Briggs, too, was taking a wait-and-see approach to the Trust. He helped design Obama’s national infrastructure bank proposal, which he said would have been a tool to promote innovative approaches to infrastructure and regional collaborations. Chicago’s could do the same, on a smaller scale, or it could simply be a way around a funding shortfall. It’s too soon to know. He also wondered how the Trust, with a relatively small staff, would manage projects as diverse as the kinds Emanuel has talked about.

“The fact that it could take on so many different types of projects is both inspiring and daunting,” he said.

In the long run, these questions may be answered by the marketplace, which after all won’t invest in projects it doesn’t believe in. The early returns are good. The retrofit jobs caught the eye of 14 potential investors. And big money — be it private equity, pension funds or investment banks — has been moving into infrastructure funds in general.

“A lot of investors are really looking for projects that provide very stable returns over long periods of time,” said D. J. Gribbin, a managing director at Macquarie Capital. “These are assets that have demand that’s pretty constant and they’re not going to fluctuate wildly. In exchange for that investors are happy with a stable return.”

But these investors have a world of deals to choose from, many in places with more experience handling P3s. The trick for Scott and Beitler lies in how to make Chicago’s projects attractive to global capital, while also making sure the city is protected in the deal. If they can strike that balance, and set up the systems to do it efficiently, they could unlock a lot of money and start to draw a road map for the many other cities that want to do the same.

And that process starts in some unlikely places, among them a nondescript water station at the end of a residential street on Chicago’s northwest side.

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Tim Logan writes about the economy and urban development for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. He has also worked for newspapers in New York and Indiana, earned a masters degree in urban affairs from St. Louis University, and won national journalism awards, including a Loeb Award for Business Journalism in 2011. He lives with his wife and young son in a brick four-family in south St. Louis that was vacant and abandoned not so long ago.

Lauren Adolfsen is a designer and illustrator based in Los Angeles. In May 2011 Lauren received her MFA in Graphic Design from Yale School of Art. Since 2003, Lauren has made claymation shorts and sold retail products under the name Snack Mountain. You can read about her latest projects at blog.snackmoutain.com.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine