Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

Volunteers unload food scraps onto the compost pile at East Capitol Urban Farm, a three-acre farm in southeastern Washington, D.C.

Credit: Institute for Local Self-Reliance

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberEDITOR’S NOTE: Zero-waste programs in places such as New York, Austin, San Diego, San Francisco and Boston have reached a critical juncture. Beyond the hype that characterized earlier aspirational vision plans, in practice these programs have brought attention to the garbage disposal problems that many cities in the U.S. either currently face or are soon to confront: the rapid disappearance of available landfill space, a shrinking demand for exported recyclables and the environmental damage inherent in ramping up incineration efforts at aging, polluting facilities. Part one of our two-part zero-waste feature looked broadly at the state of zero-waste programs in major urban centers, and how cities such as Austin are pushing to create markets that redirect commercial and organic waste away from landfills or incinerators. In this week’s feature, we dig into diversion that begins earlier in the waste cycle — efforts to decrease the amount of generated household and commercial waste, chiefly through Pay As You Throw (PAYT) and composting.

While it doesn’t yet appear in Marvin Hayes’ unofficial job description, the 46 year-old resident of South-Central Baltimore is at the forefront of efforts that may give municipal zero-waste efforts a fighting chance. Hayes is a program manager of the Baltimore Compost Collective, a relatively small operation that’s important to the 57 customers it serves in the Federal Hill, Locust Point and Riverside neighborhoods of the city. For a household contribution of $5 a week, Hayes and his crew — five students or recent graduates from Benjamin Franklin High School — will come by once a week in a van to pick up accumulated food scraps subscribers have saved. The resulting 350 pounds of discards is brought to the Filbert Street Community Garden, where it is composted and later spread onto beds of vegetables and fruit to be seeded, cultivated and nurtured during the growing season. The garden yields a welcome cornucopia, especially in an area where the nearest fresh produce is 25 minutes by car. The garden’s bounty is sold throughout the year at nearby 32nd Street Market. “Our goal is to be the small business that eventually leads Baltimore to [adopt] curbside pickup of organic waste and food scraps,” Hayes says. “We’re already providing a model for community gardens around the city by diverting 1,200 pounds of waste every month.” Hayes, a long-time youth mentor in the Curtis Bay area of the city, can check off a list of other benefits that the compost — and ultimately the garden — provide the neighborhood. His recruits get a job that pays, work to help the community and cultivate leadership skills. Local compost efforts like Hayes’ may seem small, but collectively they could generate major momentum. Organic waste stubbornly remains one of the biggest components of municipal garbage. Food scraps, yard clippings and food industry trash, among other things, constitute as much as 40 percent of the waste stream in some cities. Stepping up composting efforts point the way to large reductions in the amount of trash that has no other place to go but landfill or burning in either incinerators or waste-to-energy plants. On a more symbolic level, the garden reflects efforts in neighborhoods such as Curtis Bay to play a greater role in the city of Baltimore’s business as usual. In the last few years, students at a local high school in Curtis Bay, not far from Filbert Street, began a grassroots campaign to press for environmental justice and shutter the city’s garbage incinerator unit well within noseshot of residents and a direct threat to their health. Despite its age, the facility has been a critical link in Baltimore’s garbage disposal scheme. Without it, the city faces a scramble to process the tonnage it collects from residents citywide.

While Baltimore hasn’t unveiled a full-fledged zero waste plan like San Diego, New York, Boston and other cities have, its battle with a mounting garbage disposal problem must rely on many of the components in the zero-waste toolkit. In fact, the city has announced a goal to keep 80 percent of household food and organic garbage out of landfills or incinerators by 2040, and to cut commercial food waste in half within that same time frame. That’s already a tall order: The Baltimore sustainability office estimates the city generates 430,000 tons of trash every year, the majority of which is incinerated. By some estimates, food waste accounts for about 100,000 of those tons.

In part two of Next City’s two-part feature on options for and exigencies of Zero Waste programs in the U.S., we examine efforts to separate valuable substances out of city collections, primarily through composting of organic waste; and attempts to decrease the enormous volumes of trash that both households and companies generate, by asking residential and commercial customers to assume financial responsibility for the garbage they toss.

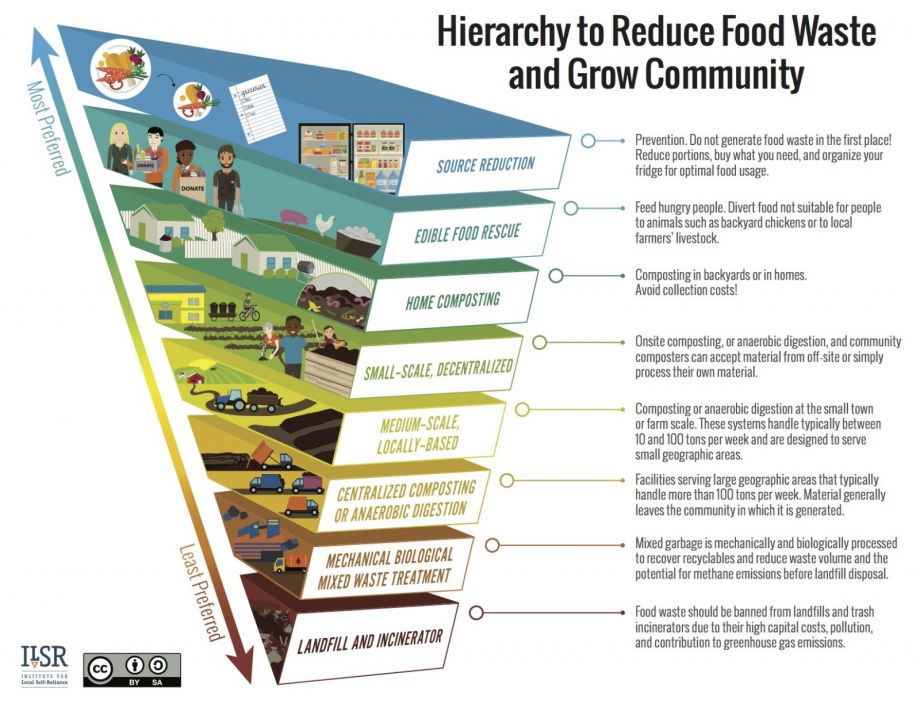

Graphic reprinted with permission of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, a national nonprofit organization working to strengthen local economies and redirect waste into local recycling, composting and reuse industries.

When it comes to cutting down on residential waste, perhaps the biggest problem is just how most people take the city garbage disposal process for granted. Yes, municipal taxes often foot the bill for getting trash gathered up and sent off. Ultimately, though, the money or effort that’s spent is buried deep in city budgets. As a result, a majority of residents have little tangible connection to just how much City Hall spends on waste removal; the work of running fleets of trucks, employing sanitation workers, running landfills or even mapping out logistics to haul out of town what’s thrown away is a distant, abstract thought few of us ever ponder.

Enter pay-as-you-throw (or PAYT for short), a solution a growing number of cities are debating as a strategy to attack the supply side of municipal waste. PAYT effectively transfers the cost of city sanitation into a monthly bill that most residents can’t help but notice.

The pro-PAYT camp favors treating trash disposal as a billable municipal utility, similar to water or electricity. Because city dwellers pay for those services regularly, they understand the direct correlation between the price municipal governments set and just how much each household uses. PAYT proponents argue that the sooner and more frequently that users come across some price for the disposal of trash, the quicker they’ll cut back on the amount of garbage they generate, and the money they spend on its removal.

PAYT has two clear benefits. For starters, the city sees a revenue stream from monthly payments. Municipal budgets get a secondary lift in the form of lower expenses. When citizens throw out less, less garbage is hauled. That means savings at several strategic points. Pickup routes often can be streamlined or trimmed. Fewer crews are needed. And cities pay less at the landfill or at transfer sites where trucks or trains move tonnage elsewhere for sorting, landfill or incineration.

“Pay-as-you-throw is unparalleled — it’s simply the most effective way to incentivize resident participation in waste diversion,” says Mark Dancy, the president of WasteZero, a Raleigh, North Carolina consulting company which has advised 1,100 communities on garbage management. “The reason is that everyone, regardless of their feelings about recycling, climate change or the environment is financially motivated to participate.”

The same logic led New York City to set aside $1 million to pay consultants to study how a pay-as-you-throw (or “save-as-you-throw” as it’s called in the Big Apple) program might work there. The study has stalled amid talk that it has encountered local opposition in the city council, and reportedly the contract between the department of sanitation and RRS, the consulting firm, has yet to be executed.

Dancy is used to city governments getting cold feet. He admits the switch to paid disposal frequently flies into political headwinds as mayors, public workers managers or city council fret over a political backlash. “There’s a temptation to kick the can down the road, no pun intended,” Dancy says, “Politicians fear they’re going to exhaust their political capital by introducing new charges.”

The grousing and mumbling stops, however, almost immediately, Dancy says. The reason: PAYT generates almost immediate results. “We don’t have a 100 percent retention rate, but close to it — that is, 98 percent — over the last 25 years.”

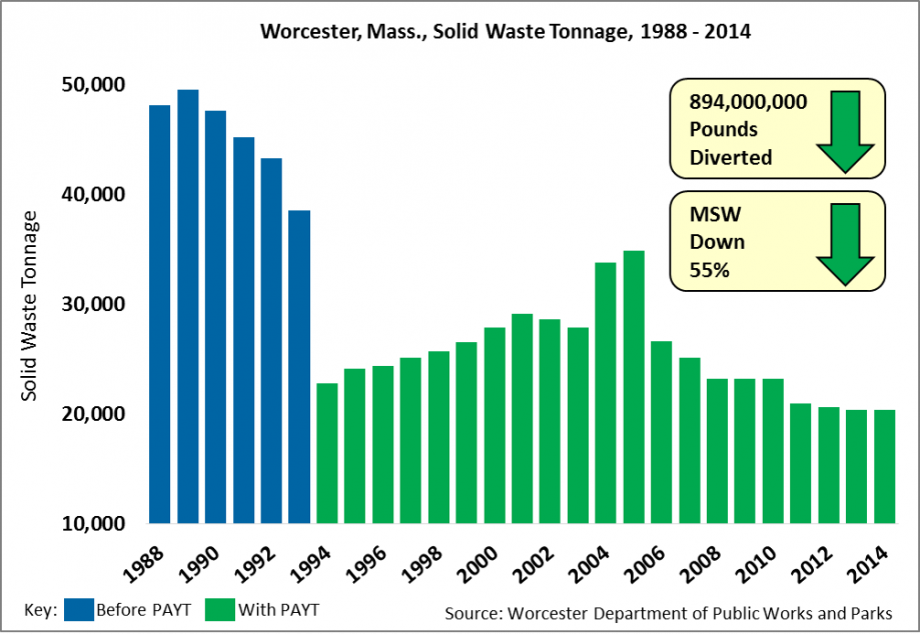

Take Worcester, Massachusetts, as a case study. In 1992, the city found itself in a budget squeeze just as the state adopted stringent guidelines for waste reduction and recycling. In search of financial relief, it set up a resident-paid garbage collection program and quickly saw results. A former solid waste commissioner reports that Worcester’s garbage fell by almost half in the first year of its PAYT program, from 43,288 tons to 22,810 tons. This decrease in garbage collected chopped the city’s outlays by a drastic $552,000, from $1.2 million to $660,000. Additionally, the city’s recycling program was revitalized almost overnight — participation jumped to 38 percent from a previous 2 percent, all within the first week.

Those metrics mirror similar results across the country. Dancy says industry studies have found that cities lower garbage generation about 44 percent by enacting for-pay disposal. That figure inspires such confidence for the chief executive that he has promised to cover the tipping fees if a city does not reach a minimum 35 percent decrease in generated trash. According to Dancy, WasteZero hasn’t yet been stuck with a bill.

Dancy’s company has drummed up a fair amount of business elsewhere in New England — 250 towns and cities, he estimates. There, city governments have found themselves backed into a corner, with literally nowhere nearby to bury and dump garbage. In 1980, Massachusetts had 300 landfills. Today, that number is under five. The region’s waste-to-energy facilities, meanwhile, are old and several already have been shut down. As a result, the only remaining choice is to foot a much larger bill to haul trash to a dump site in the South or Midwest.

As seen in Worcester, cities where residents bear the burden of paying for trash not only have higher diversion rates, but also seem to get residents more invested in recycling. Seattle and Portland, for example, have diversion rates of close to 60 percent compared to a coast-to-coast average of 34 percent according to 2015 calculations by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). A 2011 Harvard Business Review study in Italy came to similar conclusions, finding that in the area where the study was conducted, households increased the amount of waste they sorted out of direct trash by 12 percent, once a PAYT program was set up.

A look at zero-waste aspiring Austin can shed more light on PAYT’s impact on municipal budgets. In 2018-2019 forecasts, the city will collect $90.5 million in fees from garbage collection, while its Resource Recovery department, which handles sanitation among other responsibilities, will log operating expenditures of $69.7 million.

Put into practice, PAYT programs can be divided into two camps, based on how citizens take their trash to the curb. Many cities — Seattle, Portland and Austin among them — require single-family home owners to subscribe to a service and pay a monthly utility bill for renting city trash carts. The amount charged each month varies according to the size of the cart. According to Austin’s current city budget, it’s estimated that a resident using a 64-gallon cart will end up paying $291.60 for the 12 months ending mid-year. In Seattle, the monthly price for weekly pickup ranges from $29.70 for a 20-gallon cart up to $77.25 and $115.90 for 64-gallon and 96-gallon containers, respectively. The city tacks on $12.00 for each additional bag left out up to 60 pounds, and threatens to fine owners for over-filled carts.

Dancy thinks there’s a better way to drive home the message, one trash day at a time. His WasteZero consultants advise cities to opt for specially marked trash bags instead of bins or carts. Each is distinctively marked with a city logo to alert garbage crews, and available for purchase at a variety of retailers in town.

In Worcester, the municipal trash collection service uses two sizes of yellow bags. Residents can buy 10 smaller, 15-gallon size for $7.50 or 5 of the 30-gallon size for the same price.

Dancy says a large part of the effort put into setting up a PAYT system goes toward communication and education. “Uninformed residents naturally have a lot of fears about what will happen,” he says. “The more informed they are, the better.”

The first two to three weeks setting up PAYT focus on spreading the message. Outreach includes hanging tags on front doors, putting stickers on garbage pages and making sure garbage truck route drivers know what to communicate to residents as well. “It’s one of the first phases,” he says, “We have to meet with members of city government and representatives to help them explain the program to key stakeholders, one-on-one with people who live in the city, city council meetings, or even [hold] public discussions.”

Cities report two chief concerns in contemplating PAYT. The first is the equity implication of the program; how do economically disadvantaged residents cope with one more bill to pay? Different cities have taken different approaches. In Portland, Oregon, the assumption has been that low-income residents live in multi-family housing. Landlords will split garbage charges among multiple households, while single-family home residents pay a separate rate. Seattle established a hotline where residents can present their combined utility bills and make their case for a lower rate. Dancy says smaller cities he has worked with in Massachusetts have offered vouchers or given away bags to low-income residents through churches or community organizations.

The second concern is that residents will rebel against the new regulations and dump illegally (and stealthily) to skirt the charges. The surprise, says Dancy, is that this potential consequence of PAYT has proven negligible. “Everyone asks that, since it seems intuitive that it would happen,” he says of the city officials that worry about a spike in littering. “But after programs get going, it’s just not an issue. The fact is, people don’t litter like that — and it’s raised my faith in the human race.”

Ask any waste expert. What’s one of the easiest ways to quickly boost diversion rates? Composting. What’s one of the hardest? Also composting.

There are two reasons why organic waste collection and composting present zero-waste programs this sort of paradox. The apparent contradiction is rooted in just how plentiful the raw material of composting is. The flip side is just how tricky — and sometimes disgusting — the process happens to be for turning organic muck into dark, rich compost.

Start with the abundance of organic waste — food, wood, yard clippings and more — lumped into municipal trash. While there is no precise measurement of how much food households, restaurants and grocery stores throw away, even ballpark figures are staggering. The EPA estimated food loss and waste across the U.S. surpassed 38 million tons in 2014.

An added plus is that compost is more than just high-quality dirt. When done the right way, bacteria, fungi and other microbes mobilize to break down organic waste into a rich, dark earth that has restorative powers. Compost gives ordinary soil a number of big boosts, which make the plots where it’s used considerably more fertile. It binds the soil together and protects against erosion or desertification. In a city setting, compost has an extra, important benefit: It helps filter out up to 95 percent of the pollutants that are typically washed into urban stormwater streams.

Composting has the feel-good factor as well. Good samaritans know that organic waste tossed in landfills breaks down without oxygen and releases high levels of methane, a greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere. Organic waste is the number one human-generated source of methane, in fact.

A burgeoning domestic marketplace for compost is already taking note of the benefits — unlike the market for recycled materials, which has been slow out of the gate. Brenda Platt, a director at the Institute for Local Self Reliance, says one of the fastest growing markets for compost will be stormwater systems. Compost’s ability to sponge up water and leach out chemicals makes it a good choice for city systems which channel rain away from overburdened city sewers back to urban green spaces, parks, rain gardens, and even green roofs.

State transportation departments and highway authorities are another source of demand. Maryland and Texas, for example, have invested in blankets — thick, three-inch covers of composted soil. Heavy machinery such as bulldozers can install the composted soil cover alongside highway shoulders and other sloping land that runs parallel to roads, an improvement that counters erosion. California, meanwhile, is turning to compost to revitalize areas that have been ravaged by wildfires. Denver and other cities have enacted “disturbed soil” regulations that require developers to use nutrient-rich compost to replace any topsoil that is taken away during construction.

_920_2479_80.jpg)

Graphic reprinted with permission of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. The complete version is available here.

The underlying problem is that composting is easier to conceptualize than to execute properly. The process requires more forethought and effort — and in some cases infrastructure — than simply building up mounds of organic matter. The microbes essential to making compost need the right conditions to thrive, or the plots where they’re turned out can turn into stinking wretch pits. The recipe for compost done right requires air and plenty of it. Organic ingredients must be collected separately from other household trash. Meat, weeds, dairy products, fats and grease ruin cultivation and must be kept away. To get the best results, brown materials — wood and dead leaves — should be integrated in precise proportions to greens such as food waste and grass. Sites must be situated away from dumpsters and standing water. A composting system must be constructed on a concrete base.

Worries about the messier aspects of composting often run into popular and regulatory resistance, especially when big municipal sites are in question. “State permits and local zoning alone can make opening a larger-scale facility a multi-year process,” says Platt, “And that’s not factoring in how capital-intensive getting up and running can be.”

Nevertheless, composting efforts have made considerable headway. A survey conducted by Platt and Virginia Streeter for Biocycle Magazine found that composting programs enjoyed a robust growth spurt between 2014 and 2017. In that time, the number of curbside programs grew from 79 to 148, reaching an estimated 5.1 million households, a jump of more than 2.4 million since the first tally. New York City’s program is the largest in the country, reaching approximately 1.6 million households. The same study found that an additional 318 communities, representing 6.7 million households, have access to compost drop-off programs.

Garbage works departments have taken notice, too. Organic collection is the law in cities such as Portland, Seattle and San Francisco. In Denver, Charlotte Pitt, an operations manager for the city’s solid waste department, recently said that a pickup in the city’s organics collection — food, yard waste and the like — could result in Denver steering 40 percent or more of its garbage out of a landfill. The city currently provides the service for more than 18,000 households, all of which have requested and received a special container to set aside their organics.

Yet, when it comes to the rapid expansion of centralized compost facilities, the waste industry has a cautionary tale to tell from recent history. In 2009, the Wilmington Organics Recycling Center began operations in Delaware and was soon composting 200 tons a day while taking in organic disposals from a 400-mile radius up and down the Mid-Atlantic, from as far afield as New York City and Washington, D.C. At first, work went smoothly and met federal and state standards. That changed when management pushed to boost input from 200 to 600 tons daily. The facility struggled to keep up and the pressure led to a breakdown in the quality of the compost it produced. One problem was contamination levels in organic waste the plant brought in, evident in the glass and plastic that customers complained showed up in the compost they bought. The plant also emitted a foul smell; from 2012 to 2014, the facility was named in hundreds of odor complaints. The rancor rose to such a level that the state of Delaware stepped in to refuse renewal of the center’s permit.

According to Platt, the moral of Wilmington’s story is that the best way to expand composting as a solution to urban waste sprawl lies in the middle ground between big units that provide scale and smaller community and urban gardens to help increase outreach. “The position I advance is having a diverse infrastructure,” says Platt, referring to both large-scale, centralized facilities and local community composting programs.

Embracing both avenues, she points out, without overwhelming either one, helps to build scale as well as community participation and support. “The smaller-scale solutions can come on faster, are cheaper to build, introduce the culture of composting know-how at the community level and create more jobs per ton processed. Platt’s team at ILSR has recently published a 71-page guide to back up their support of community-based compost work.

Composting still runs up against fears of olfactory challenges and squeamish citizenry who will find it hard to get onboard. A New York Times story — on how low participation rates in the city’s annual $15 million-plus organics collection program generated a mere 43,000 tons — quoted residents who claimed their neighbors hesitated to join because they were repulsed by the slime and stench left in their special brown city composting receptacle after trucks had left.

While many conscientious city dwellers are moving past the gag factor, the answer to boosting the amount of organic waste removed from city garbage collections may be underfoot, and as close as the kitchen sink.

Food scraps, yard clippings and food industry trash constitute as much as 40 percent of the waste stream in some cities. Stepping up composting efforts reduces the amount of trash that has no other place to go but landfill or burning in either incinerators or waste-to-energy plants.

Kendall Christiansen, a solid waste and recycling consultant who was the founding assistant director of New York City’s recycling program, says garbage disposers the ravenous grinding machines attached to the sink plumbing in many household kitchens, may hold the key to complement compost collection and divert still more organic waste from residential household trash. Disposals chew up all manner of rinds, stems, cores, or any leftovers and cooking waste imaginable. The mush can then be rinsed away down the sink into a city’s wastewater network, where the thinking is it can later be filtered out, cleaned and composted as “biosolids.”

Between 2012 and 2015, Christiansen led a six-city study of just how well the idea might work. Sponsored by disposal manufacturer InSinkErator, it covered a total of 432 households in Philadelphia, Tacoma, Milwaukee, Boston, Chicago and Calgary and examined a variety of housing structures including multi-unit buildings and single-family homes and targeted working-class communities. On average, the volume of food waste participants turned out was cut 30 percent. The city of Philadelphia, in fact, came away so impressed that it passed a building code requiring that all new residential construction include sink disposer units. The city of Los Angeles, meanwhile, is conducting its own study with results to come perhaps later this year.

Skeptics caution that many a city’s aging plumbing infrastructures may strain at the increased flow of organics-thickened wastewater, and express concern over the environmental effect on marine life of releasing treated slurry into area waterways. Also, depending on where you live, those biosolids may finish their journey in a landfill or incinerator anyway, even after all that treatment. The most responsible approach is to reduce your food waste imprint so there’s less to dispose of or compost to begin with.

For Christiansen, the biggest takeaway is that cities may have hit upon the right time to expand the gathering of organics from one exclusively centered on curbside waste collection to a responsibility shared by garbage and water departments. “It’s a new approach that recognizes that food scraps are mostly water, something which can be conveyed through pipes in order to leverage existing utility capabilities instead of using trucks at considerable additional expense and effort,” he says.

The list of places that have made official zero-waste declarations remains small. At the same time, a growing cadre of municipalities (and states) inch toward goals that may not brandish the official zero-waste label, but which yield remarkably similar results. Consider that 139 professionals have already registered for a forthcoming three-day “Zero Waste Principles and Practices” course offered by the nonprofit Solid Waste Association of North America (SWANA), an industry group representing public works departments and waste companies, in collaboration with the California Resource Recovery Association.

For now, the state of zero-waste is a balancing act, says David Biderman, president of SWANA. “Is the glass half full or half empty?” he ponders. “I don’t think identifying aggressive diversion goals and [then] having to change them is necessarily a defeat, but rather a mid-term correction.”

Pullquote photo by Alan Levine / CC BY 2.0.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The original version of this story misidentified the farm in the opening photo of the story, and misspelled Kendall Christiansen’s last name. Both errors have been corrected.

James A. Anderson is an English professor at the Lehman College (Bronx) campus of the City University of New York.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine