Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberPlanners and urban designers often face an uncomfortable paradox: People tend to prefer neighborhoods that developed organically with the contributions of many over those that were master-planned by a small group of experts. City makers love to use terms like organic, spontaneous and authentic, but tend to plan and design areas that limit these very qualities. We faced this paradox in a very explicit way when Gehl, where we work as urban designers, was invited by the government of Buenos Aires to provide design advice for an ambitious plan led by the city’s Secretary of Social and Urban Inclusion to redevelop the Argentine capital’s most iconic resident-built informal settlement. The plan was to turn Villa 31 — villa is Argentinian slang for slum — into a neighborhood, a barrio.

Villa 31 is one of the most interesting, rich and vibrant neighborhoods in Buenos Aires. It has the grain and scale of the medieval settlements tourists flock to in places like Siena, Italy. It has the street life, with kids running and playing, that cities like New York and Melbourne hope to achieve in their Play Streets initiatives. With streets buzzing with bicyclists and pedestrians, it has a modal split more similar to Copenhagen and other transportation trendsetters than to other Buenos Aires neighborhoods.

Yet one must be careful to not over-romanticize these qualities.

Located in a strategic location adjacent to the city’s wealthiest neighborhood, Villa 31 stands as a painful reminder of Argentina’s deep socioeconomic disparities. While most of the city is revered as a sophisticated metropolis, 37 percent of the informal settlement’s 8,000 homes lack a kitchen and a quarter of them don’t have a toilet. Some residents carry an extra pair of shoes to change into after walking the muddy streets, and some of the corridors are so narrow that they leave hundreds of families out of the reach of emergency vehicles. Most homes don’t have potable water and are not connected to the sewage network. Electricity is available through dangerous informal connections that have resulted in electrocutions and deadly explosions. The majority of the houses are overcrowded and lack adequate indoor air quality. Although the villa is adjacent to a transit hub, none of the transit lines enter the community and pedestrian access is further limited by gang control of some access roads.

After 80 years of neglect, the local municipal government has decided to tackle the challenge and extend its reach, services and infrastructure into Villa 31. The intent is to elevate the quality of life to the same standards as the rest of the city. This massive and complex task is being led by a motivated team of young architects, engineers, sociologists and public policy professionals. Gehl was brought into the team to help advance the social mission of the project through urban design, with an emphasis on sustainable mobility and public space.

As part of our work, we studied public life in seven neighborhoods that were representative of the diversity of Buenos Aires and learned from the public outreach team that has been working with the residents for almost two years. Our findings revealed that the villa outperformed the wealthier parts of the city in key indicators of urban vibrancy and sustainable mobility. There are more people walking, cycling and spending time socializing, playing and people-watching in the streets and spaces of Villa 31 than in the six neighborhoods we studied. What’s more, we realized that many publicly-subsidized social housing projects over the past century had delivered worse outcomes (in terms of safety, security and health) than the informal slums people built and inhabited before government intervention.

There is no question of the urgent need to extend public services into this area. For decades the residents of Villa 31 have demanded basic infrastructure and governmental presence, yet the more time we spent in the community, the more we came to appreciate the urban infrastructure already built by the people of the neighborhood. These families face severe deprivation in many areas but amid the scarcity, their neighborhood offers some of the qualities that some of the most privileged cities seek, including walkable streets and a vibrant public life.

Working with a passionate and dedicated team — Diego, Lucho, Licho, Nacho and Juani — Gehl devised strategies for connecting the neighborhood, so long on its own, with its formal surroundings. This goal of making the community more physically accessible complements the complex process of integrating the villa into the formal social and financial fabric of the city. We helped design streets and spaces to connect the micro-communities within the community to one another, to enforce the notion that the public realm is truly the common ground and lifeblood of the district.

As our designs developed, we realized the risks of redevelopment. Adhering to modern buildings standards would mean widening streets, restricting entrepreneurialism and possibly increasing construction costs. The community would have to give up some of its most powerful attributes in order to meet code.

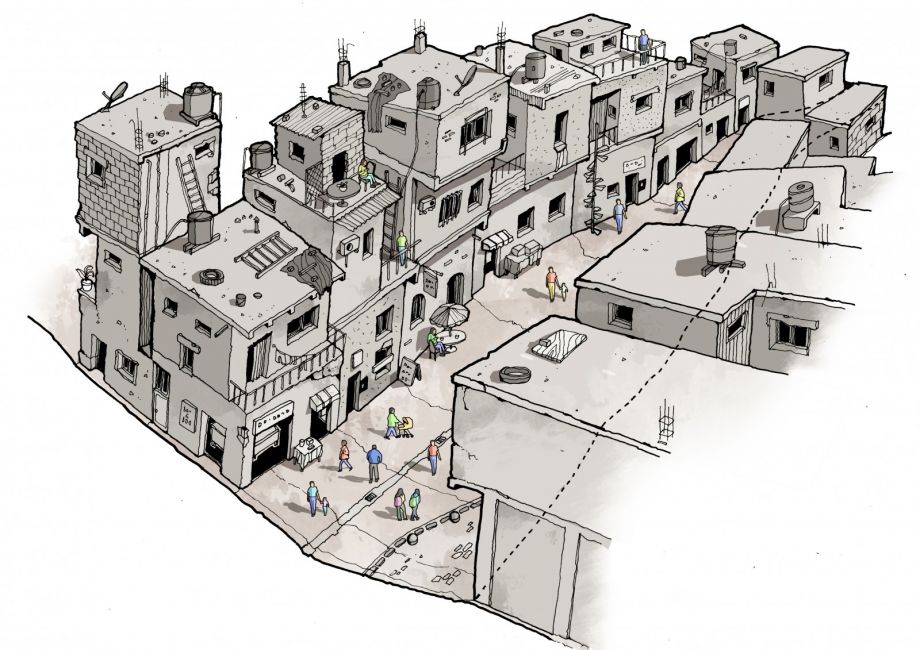

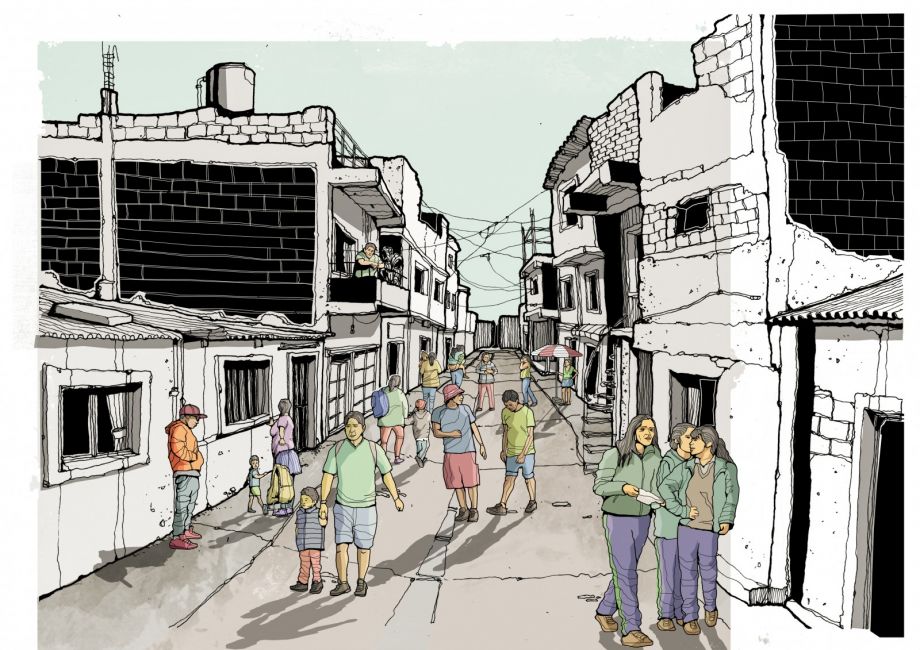

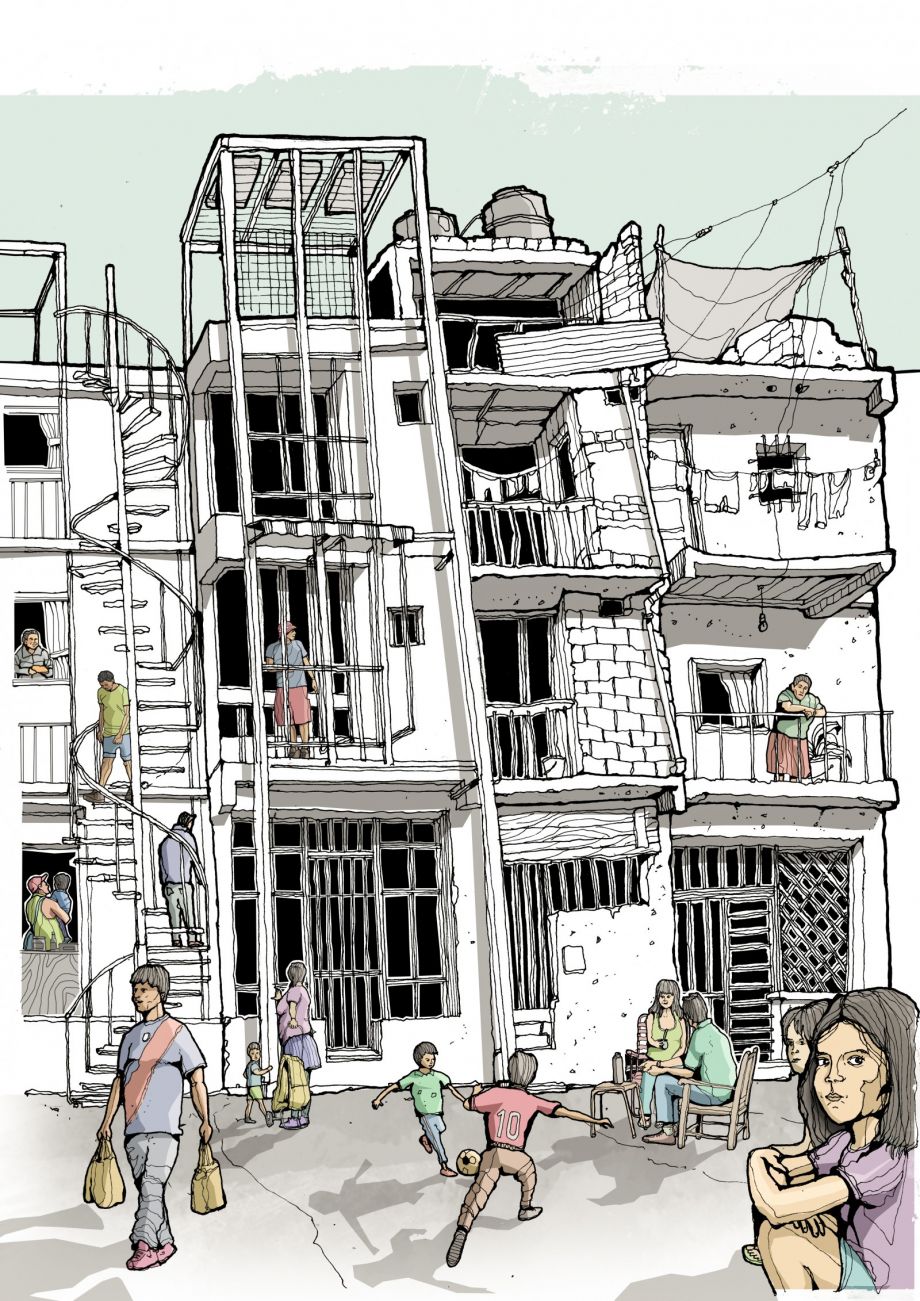

The architects of Villa 31— its residents — have created a place with qualities that need to be preserved as professional architects come in. Here, illustrated by local artists Fernando Neyra are the top five design lessons we learned from Villa 31.

Built by the residents on publicly-owned land near the main transit hub in the city, Villa 31 has offered migrants and low-income families something that neither the market nor most government programs could offer: the opportunity to live in proximity to the jobs, services and amenities the city has to offer. In Argentina, like in the United States and Europe, there is an unmet demand for affordable housing near employment centers. Unfortunately, the supply of affordable housing, including public housing, is often confined to residential areas in the periphery that lack adequate jobs and public transit. This limits residents’ opportunities and condemns them to wasting valuable time on a senseless commute.

In a city marked by skyscrapers and fast-moving traffic on eight-lane avenues, the narrow streets and compact form of the villa offers a break from the noise and bustle of urban life. Although Villa 31 is one of the densest neighborhoods in the city, most buildings are under five stories tall. Street width ranges from three to 16 meters, generating a network of narrow shared streets with a pleasant microclimate. The dense blocks formed by narrow buildings with active ground floors and open balconies ensure that there are always eyes on the street. Rather than conforming to a grid, the streets curve around the buildings, generating a network of curved passages that reveal different views of the district and its surroundings. These irregular passages vary in width, making room for small plazas and gathering spaces. Narrow alleys serve as a shortcut among parallel streets allowing pedestrians to take shorter and more direct routes than what vehicles can.

Narrow streets and a constant stream of activity forces drivers to circulate slowly within the fabric of the villa. The slow pace of traffic generates a social environment that is safer and quieter than other areas of the city that are engineered for the flow of automobiles. Villa streets become a meeting point — a place of casual exchange and frequent encounters. Even from an early age, young children can gather to play outside their home unattended but within shouting distance from an adult. Walking through the streets of the villa, you see families pull their chairs in front of the house to chat with neighbors or look over the kids. You see older residents engage in conversation with passersby from their living room window or balcony. A small ground floor unit in the villa allows an elderly person to live independently and still engage in the life of the community.

Homes in the villa are more than a place to live — they are platforms for economic progress. An immigrant family may start with a two-room single-story house. A gate or a window that faces the street is all they need to start a small shop. Entrepreneurial ideas can be tested without the cost and risk of renting a commercial space. If the business fails, it can be converted to a new and better business idea at the same location. If business succeeds, it may expand to fill the first floor while revenue from the business goes towards a second-story addition that becomes a home. A third floor with independent access becomes an apartment for a cousin or a renter and their partner to move in. The house is constantly adapting and changing; it can get subdivided when the family grows, or rented when a member moves out. Many of the residents of the villa live outside of the formal banking system so a bigger house becomes both a form of savings as well as a revenue stream. Over time, a successful business can become a well-known neighborhood asset that allows people to meet their needs within walking distance. Today one out of every five buildings in Villa 31 holds a business. A single narrow street holds a produce market, an internet cafe, hairdresser, laundry, a sandwich shop and even a dentist office. Each of these business stands as a testimony of the entrepreneurial drive of the residents.

Traditional public housing projects place people into regulated, standard modules; they are predictable shapes repeated in orderly rows. Personalized changes to the exterior of the homes are discouraged or forbidden as they affect the architectural purity of the vision. Free from monolithic aesthetic ideas, the villa allows people to project their personality onto the houses. An attentive walk in the villa reveals the pride that many people have in their home, as they choose colors and materials that reflect their taste and preferences. On a quiet street, a family places a hand-painted tile with the house number and their name; the painted house reminds people passing by of the family who proudly lives there.

For decades, residents have demanded change. Today, many welcome the improvements that the government is making in the neighborhood. It can’t be said enough that it’s essential to not romanticize conditions that emerged out of scarcity and need. However, it is also necessary to elevate the values and strengths of the community so to retain them in the redeveloped neighborhood and apply their lessons to other development projects.

New investment must be directed at real needs while respecting the social structures that have allowed the community to stay strong in the face of adversity. We believe that the urban form of the villa with its proximity to work, flexible and adaptable architecture, compact walkable streets and active ground floors has contributed to both the strong social connections between residents and the remarkably resilient structures they inhabit. Architects involved in the creation of public housing in Latin America and elsewhere would do their residents a service by studying and learning all they can from self-built communities like Villa 31. City leaders need to embrace the paradox represented by places like the villa. These urban spaces need public support that doesn’t overregulate the organic life that has bloomed in its absence.

Special thanks to the entire Barrio 31 team and especially Diego, Lucho, Licho, Nacho and Juani. Special thanks also to David Sim who influenced our approach to this project and the ideas in this article.

Jeff Risom is the managing director of Gehl in the United States.

Mayra Madriz is an urban designer for Gehl, an international urban design studio with offices in Copenhagen, San Francisco and New York.

Fernando Neyra is an illustrator and graphic designer based in Cordoba, Argentina.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine